HKS/Jahrbuch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

5 1 2 1 4 6 8 3 3 5 7 9 10 7 8 9 10 11 12 11

A B C D E F G H I J K L 1 1 2 2 Linie 844 Die neuen RadBusse RadBus Ahr-Voreifel bringen Sie weiter Neuer Name, gleiche Vorteile: Alle RegioRadler sind ab Jetzt unter 2020 als RadBus unterwegs. So erkennen Sie auf den ersten Blick, dass es sich bei dem nützlichen Ausflugshelfer um radbusse.de einen Bus handelt, der Sie und Ihr Fahrrad mitnehmen kann. buchen! RadBusse 3 Vulkan- 3 Bequeme Anfahrt Expreß Da die schönsten Radrouten nicht gleich vor der Haustür im nördlichen beginnen, bringen Sie jetzt insgesamt 18 RadBusse auf Raderlebniskarte teilweise neuen Streckenabschnitten zu den besten Einstiegspunkten für Ihre Tour. Sparen Sie sich Ihre Energie Rheinland-Pfalz – für die wirklich schönen Ausblicke entlang der Radstrecke „RadBusse und lassen Sie die RadBusse die teilweise beschwerliche Anfahrt übernehmen. Da sind zum Beispiel die Anstiege Raderlebniskarteim nördlichen in der Eifel oder im Hunsrück, die ungeübten Radfahrern so einiges abverlangen. RadBus-Haltestellen entlang der Mosel, Ruwer, Sauer, Ahr, Nette und Lahn garantieren Rheinland-Pfalz“ ebenfalls, dass Sie jederzeit Ihren Ausflug beenden können, 4 ohne „auf der Strecke“ zu bleiben. Linie 821 RadBus Nettetal rolph.de Flexibel unterwegs 4 Gerade die Kombination aus Bussen und Bahnen in Rheinland-Pfalz bilden eine gute Grundlage für Ihren Ausflug. So liegen neben den Bushaltestellen auch viele Lahntalbahn Bahnhöfe entlang der gut ausgeschilderten Radwege. Damit sind Sie besonders flexibel unterwegs und können Ihre Tour bestmöglich vorbereiten. 5 5 Online-Reservierung Übrigens… Sollte an Ihrer Ausflugsstrecke kein RadBus im Einsatz sein, Sicher ist sicher - Reservieren Sie Ihre Fahrrad- können Sie in Rheinland-Pfalz Ihr Fahrrad auch in vielen plätze unter radbusse.de und starten Sie mit dem Nahverkehrszügen montags bis freitags ab 9 Uhr sowie Bus entspannt in Ihren Ausflug. -

Eifelkreis Bitburg-Prüm

Ausgabe 51. KW 2010 EIFELTORIAL www.eifeltorial.de Klares Nein meinen die Leute das in der Tat leider ernst. Die zu Mini-Atomkraftwerken Bürger wollen den Atomspuk nicht. Der Trierer Windkraft-Unternehmer Jörg Temme Die Kreisverwaltung des Eifelkreises Bitburg- sorgt für große Aufregung im kleinen Ort Seffer- Prüm lehnte im Jahr 2007 Temmes Atompläne- weich im Eifelkreis Bitburg-Prüm. Bürger wollen Antrag ab. Doch wie zuvor gesagt, urteilte das keine kleinen in den Boden vergrabenen Klein- Verwaltungsgericht Trier im Jahre 2008 zuguns- Atomkraftwerke des Herrn Temme. So hatte „ul- ten von Temme. Schlussendlich wurde der Trierer kigerweise“ bereits Anfang des Jahres 2008 das Gerichtsbeschluss im Jahre 2009 vom Oberver- Verwaltungsgericht Trier den ersten Bauabschnitt waltungsgericht in Koblenz gestoppt. Temmes einer sogenannten Atomforschungsanlage in Sef- erneuter Genehmigungsversuch wurde vor ei- ferweich genehmigt. Die Temme AG will dort wohl nigen Wochen abgelehnt. Temme sollte wirklich immer noch Kleinreaktoren bauen. Der positive das jahrelange Atomspuk- und Genehmigungs- Richterspruch aus dem Jahre 2008 galt zunächst Hickhack beenden. Wir brauchen weder in Sef- einmal allerdings nur für die Errichtung eines 3 x ferweich noch in einem anderen Dorf im Boden 3 m großen unterirdischen Baubehälters für erste vergrabene Atomkraftwerke. Testzwecke. Wie es seinerzeit hieß, bedeute dies noch nicht, dass es eine strahlenschutzrechtliche Ist die Eifel, Hunsrück und Mosel Genehmigung gäbe. (das Aktenzeichen lautet nur unliebsames Trierer Hinter- AZ: 5K798/07.TR). land? Die Temme AG aus Trier will in dem kleinen Ei- Dass ein Gericht im Jahre 2008 ein positives Ur- feldorf mit nicht genannten ausländischen Inves- teil für Temme zum Thema fasste, ist unglaublich toren einen Kleinreaktor bauen, der Energie ins aber leider wahr. -

Hxwvfkodqg Ndxihq N|Qqhq

Wo Sie welt-sichten in Deutschland kaufen können Plz Stadt P&B Presse & Buch, Bahnhofsbuchhandlung, Wienerplatz 4, 01069 Dresden Unternehmensgruppe Dr. Eckert, BHB Filiale LUDWIG, Im Bahnhof Dresden-Neustadt, Schlesischer Platz 1, 01097 Dresden Lagardère Travel Retail, Deutschland GmbH, Bahnhofsbuchhandlung, Wilhelmine-Reichard-Ring 1/Flu, 01109 Dresden Unternehmensgruppe Dr. Eckert, BHB Filiale LUDWIG, Promenaden Hbf, Willy-Brandt-Platz 5, 04109 Leipzig Unternehmensgruppe Dr. Eckert, BHB Filiale LUDWIG, Bhf. Friedrichstr., Georgenstr. 14-18, 10117 Berlin Unternehmensgruppe Dr. Eckert, BHB Filiale LUDWIG Alexanderpl, Bhf. Alexanderplatz, Dircksenstr. 2, 10178 Berlin K Presse+ Buch, Bahnhofsbuchhandlung, B-Ostbahnhof, Am Ostbahnhof, 10243 Berlin P & B Press + Books, Bahnhofsbuchhandlung, Berlin Ostkreuz BHF, Sonntagstr. 37, 10245 Berlin k - presse und buch, Bahnhofsbuchhandlung, Hardenbergplatz 3, 10623 Berlin k - presse und buch, Bahnhofsbuchhandlung, Adenauer Platz, 10629 Berlin Unternehmensgruppe Dr. Eckert, BHB Filiale ECKERT, im Bhf. Südkreuz EG Westhalle, Naumannstraße 90, 12101 Berlin Unternehmensgruppe Dr. Eckert, BHB Filiale ECKERT, Im Bahnhof Schöneweide, Michael-Brückner-Str. 42, 12439 Berlin P&B Press&Books, c/o BHG Bahnhofs-handels-Vertriebs, Bahnhofsvorplatz, Badstraße 1-3, 13357 Berlin k - presse und buch, Bahnhofsbuchhandlung, (Tegel), Haupthalle-Bon Voyage, 13405 Berlin Lagardère Travel Retail, Deutschland GmbH, Fil. 23 - Lager Berlin HBF, Lübarser Str. 25-27, 13435 Berlin k - presse und buch, Bahnhofsbuchhandlung, Seegfelder -

Lvi-Info-51.Pdf

Editorial Ab wieviel PS zählt man als Kunde? Vielleicht gibt es zur Zeit so viele Gräben und geperrte Straßen in der Haupstadt weil es während 20 Jahren fast keine großen Baustellen zur Erneuerung der Infra- struktur gegeben hat. Und derjenige, der den Mut hat diese nicht gerade populären aber notwendigen Arbeiten auszuführen erntet natürlich die Kritik. Wir als LVI stellen mit Genugtuung fest, dass im Anschluss an solche In- frastrukturarbeiten dem Fahrradverkehr endlich wieder Rechnung getragen wird. Auch wenn wir bei unserer Forderung bleiben, dass ein Gesamtkonzept zum Radverkehr erstellt werden muss. Selbst der Geschäftsverband hat erkannt, dass es zur Zeit genügend Parkplät- ze für PKWs in der Haupstadt gibt und zwar in Parkinghäusern, welche über Jahre gefordert wurden. Also soll man jetzt auch den zweiten Schritt tun und dem nichtmotorisierten Verkehr den Raum wieder geben welcher ihm als gleichberechtigter Partner zusteht. Schließlich wurde auch niemand gefragt, als in den 60er Jahren die Städte au- togerecht umgebaut wurden. Zu dieser Zeit fehlte, wenigstens in Luxemburg, die Weitsicht, dass man nicht grenzenlos den motorisierten Individualverkehr fördern kann. Irgendwo liegt die Grenze und die ist mittlerweile ja nicht nur er- reicht, sondern maßlos überschritten. Es wird wieder Geschrei geben wegen der Parkplätze, welche in der haupt- tädtischen Avenue Marie-Thérèse und der Avenue Monterey oder in Esch in der Kanalstraße Radpisten zum "Opfer" gefallen sind. Aber es ist dies eine Ent- wicklung in die richtige Richtung. Eine Stadt zum Leben und Verweilen und nicht zum Ersticken und Zuparken. Und als Radfahrer sehen wir nicht nur unsere eigenen Interessen. Wie wäre es z.B., die "Place de la Constitution" um die "Gëlle Fra" in eine der schönsten Ter- rassen inmitten der Hauptstadt zu verwandeln ? Und zum Boulevard Roosevelt hin könnten wie bis jetzt die Busse ihre Touristen-Kunden bequem anliefern und abholen. -

Mobilitätskonzept Trier 2025 Schlussbericht März 2013 Dr.-Ing

Mobilitätskonzept Trier 2025 Schlussbericht März 2013 Dr.-Ing. Ralf Huber-Erler Prof. Dipl.-Ing. Carsten Hagedorn Ingenieure für Verkehrsplanung Q S Topp Huber-Erler HaAeBCrD Stadt Trier Mobilitätskonzept 2025 Schlussbericht Textband Dr.-Ing. Ralf Huber-Erler Dipl.-Ing. Sebastian Hofherr März 2013 Julius-Reiber-Straße 17 D - 64293 Darmstadt Telefon 06151 - 2712 0 Telefax 06151 - 27122 0 [email protected] www.rt-p.de Steuernummer 07/360/30092 ID-Nummer DE 111 686 630 Vorwort Nach einem umfangreichen Erarbeitungsprozess wurde am 5. Februar 2013 das Mobilitätskonzept Trier 2025 („Moko“) vom Stadtrat einstimmig beschlossen. Es besteht also ein breiter Konsens über alle Parteigrenzen hinweg, in welche Richtung die weitere Entwicklung des Verkehrs in unserer schönen Stadt verlaufen soll. Dies ist eine hervorragende Basis für eine kontinuierliche zielgerichtete Umsetzung der einzelnen im Moko enthaltenen Maßnahmen und somit der Steuerung der weiteren Entwicklung aller Verkehrsträger im Bereich der Stadt Trier in den kommenden 15 Jahren. Die Grundlage des Moko bildet das bereits im Jahr 2006 im Rahmen eines Bürgerforums erarbeitete Ziel „Trier 2025: mobil – umweltfreundlich – lebenswert!“ und der darauf aufbauende Beschluss des Stadtrates von 2009 zur deutlichen Stärkung des so genannten Umweltverbundes (Bus-, Bahn-, Rad- und Fußverkehr). Das Konzept versteht sich dabei als ein integrierter Verkehrsentwicklungsplan, der die Belange aller Verkehrsträger und Personengruppen in einem ausgewogenen Verhältnis berücksichtigt. Im Sinne einer ganzheitlichen Planung werden neben den Aspekten der Verkehrsabwicklung auch die Belange des Städtebaus und der Umwelt, die vom Verkehr erheblich beeinflusst werden, berücksichtigt. Darüber hinaus finden neben baulichen auch organisatorische Maßnahmen des Mobilitätsmanagements einen breiten Raum im Zielkonzept des Moko. Eine enge Verzahnung des Konzeptes besteht mit dem parallel in Aufstellung befindlichen Flächennutzungsplan, dessen Flächenausweisungen auf die daraus resultierenden Folgen im Verkehrssektor überprüft wurden. -

Praxis Urbaner Luftseilbahnen Arbeitsbericht Nr

Praxis urbaner Luftseilbahnen Arbeitsbericht Nr. 1 Juli 2016 Autoren Max Reichenbach, Maike Puhe Projekt Hoch hinaus in Baden-Württemberg: Machbarkeit, Chancen und Hemmnisse urbaner Luftseilbahnen in Baden-Württemberg KIT – Die Forschungsuniversität in der Helmholtz-Gemeinschaft 2 Projektinformation Projekttitel: Hoch hinaus in Baden-Württemberg: Machbarkeit, Chancen und Hemmnisse urbaner Luftseilbahnen in Baden-Württemberg Förderung des Projekts: Ministerium für Verkehr Baden-Württemberg Hauptstätter Str. 67 70178 Stuttgart Durchführung des Projekts: Karlsruher Institut für Technologie (KIT) Institut für Technikfolgenabschätzung und Systemanalyse (ITAS) Institut für Verkehrswesen (IfV) Projektleitung: Maike Puhe (ITAS) Karlsstr. 11 76133 Karlsruhe Bearbeitung Arbeitsbericht Nr. 1: Max Reichenbach (ITAS) [email protected] Maike Puhe (ITAS) [email protected] Titelgrafik: Max Reichenbach (ITAS) Empfohlene Zitationsweise: Reichenbach, M. & Puhe, M. (2016). Praxis urbaner Luftseilbahnen. Projekt „Hoch hinaus in Baden-Württemberg: Machbarkeit, Chancen und Hemmnisse urbaner Luftseilbahnen in Baden-Württemberg“, Arbeits- bericht Nr. 1. Karlsruhe: Institut für Technikfolgenabschätzung und Systemanalyse. Einordnung im Projektkontext Im Projekt „Hoch hinaus“ wird in einem ersten Schritt die bisherige Praxis urbaner Luftseilbahnsysteme untersucht. Die Ergebnisse dieser ersten Arbeitsphase sind im vorliegenden Arbeitsbericht Nr. 1 dargestellt. Die folgenden Schritte dienen der vertieften Untersuchung potentieller Luftseilbahnverbindungen in -

Trier – Wittlich – Koblenz

TRIER – WITTLICH – KOBLENZ Trier ▸ Wittlich ▸ Koblenz Koblenz ▸ Wittlich ▸ Trier 28.04. 28.04. 28.04. 28.04. 28.04. 28.04. 28.04. 28.04. 28.04. 28.04. 28.04. 28.04. 28.04. 28.04. 28.04. 28.04. Betriebstage 29.04. 29.04. 29.04. 29.04. 29.04. 29.04. 29.04. 29.04. Betriebstage 29.04. 29.04. 29.04. 29.04. 29.04. 29.04. 29.04. 29.04. 01.05. 01.05. 01.05. 01.05. 01.05. 01.05. 01.05. 01.05. 01.05. 01.05. 01.05. 01.05. 01.05. 01.05. 01.05. 01.05. Anmerkung 13 1 9 • 1 10 • 9 1 Anmerkung 1 4 7 7 1 8 • 1 Trier Hbf ab 6.44 9.55 10.15 14.14 15.09 17.15 Koblenz Hbf ab 7.41 13.41 17.41 Schweich an 7.00 10.05 10.29 14.27 15.20 17.29 Kobern-Gondorf an 7.52 13.52 17.52 Schweich ab 7.02 10.07 11.10 14.35 16.09 18.12 Kobern-Gondorf ab 7.55 13.55 17.55 Hetzerath an 7.10 10.12 I 14.43 16.16 18.20 Treis-Karden an 8.10 14.10 18.10 Hetzerath ab 7.12 10.14 I 14.50 15.25 16.18 18.23 Treis-Karden ab 8.12 14.12 18.12 Wittlich an 7.29 10.23 11.35 15.07 15.34 16.30 18.40 Cochem an 8.19 14.19 18.19 Wittlich ab 10.35 11.37 15.45 19.10 Cochem ab 8.21 14.21 18.21 Bullay an 10.47 11.56 15.56 19.22 Bullay an 8.29 14.29 18.29 Bullay ab 10.50 16.02 19.25 Bullay ab 8.33 12.41 14.33 18.33 Cochem an 10.59 16.11 19.34 Wittlich an 8.45 13.00 14.45 18.45 Cochem ab 11.02 16.13 19.36 Wittlich ab 8.50 9.07 13.07 14.49 15.32 17.20 19.20 Treis-Karden an 11.09 16.20 19.43 Hetzerath an 8.59 I 13.24 14.58 15.49 17.37 19.37 Treis-Karden ab 11.11 16.22 19.45 Hetzerath ab 9.02 I 13.26 16.15 17.39 19.39 Kobern-Gondorf an 11.26 16.37 20.00 Schweich an 9.07 9.32 13.34 16.23 17.47 19.47 Kobern-Gondorf ab 11.28 17.00 20.13 Schweich ab 9.10 9.59 14.30 16.59 17.49 19.49 Koblenz Hbf an 11.40 17.14 20.28 Trier Hbf an 9.41 10.14 14.43 17.12 18.03 20.03 1 Trans Europ Express mit historischer E-Lok 8 fährt weiter nach Wellen 13 gemeinsame Ausfahrt in Trier-Ehrang _ mit Zug in Richtung Gerolstein um Tarifzonengrenze 4 über Trier-West ohne Verkehrshalt 9 kommt von Nennig 6.53 Uhr (kein Verkehrshalt) 7 fährt weiter nach Nennig 10 kommt von Saarbrücken • mit Bahnpostwagen Stand: März 2018 – Alle Angaben ohne Gewähr. -

Entdeckerfahrplan.Pdf

2021 Freizeiterlebnis mit Bus und Bahn Entdeckerfahrplan Ihre Freizeitziele an den schönsten Strecken im VRT Gültig ab 1.1.2021 INHALT Übersicht Freizeitstrecken im VRT 3 Tickets im VRT 4 Tickets zu Zielen außerhalb des VRT-Gebiets 6 Region Mosel 8 auf der Moselstrecke zwischen Trier und Cochem/Koblenz 8 auf der Obermoselstrecke zwischen Trier und Palzem/Metz 12 auf der Mosel-Syretal-Strecke zwischen Trier und Luxemburg 16 auf der Moselweinstrecke zwischen Bullay und Traben-Trarbach 20 zwischen Trier und Schweich 24 zwischen Trier und Neumagen-Dhron 28 zwischen Neumagen-Dhron und Bernkastel-Kues 30 zwischen Bernkastel-Kues und Traben-Trarbach 34 RadBusse an der Mosel 38 Region Eifel 42 auf der Eifelstrecke zwischen Trier und Jünkerath/Köln 42 zwischen Trier und Irrel 46 zwischen Trier, Bitburg und Prüm 50 zwischen Gerolstein, Prüm, Clervaux und St. Vith 54 zwischen Gerolstein und Cochem 58 zwischen Daun und Bernkastel-Kues 62 zwischen Daun, Kelberg und Ulmen 66 RadBusse in der Eifel 70 Region Saar-Hunsrück 72 auf der Saarstrecke zwischen Trier und Taben/Saarbrücken 72 zwischen Trier, Waldrach und Morscheid 76 zwischen Trier, Thalfang und Erbeskopf 80 zwischen Trier und Türkismühle 82 zwischen Saarburg und Konz 86 RadBusse im VRT 90 2021 Besondere Hinweise Titelmotive 3 4 Fahrplandaten: Bitte beachten Sie: Die hier abgebildeten 1 Die Porta Nigra in Trier 5 2 Fahrpläne sind zum Teil nur Auszüge aus den VRT-Fahr- © Rheinland-Pfalz Tourismus 1 GmbH, Dominik Ketz plänen. Weitere Fahrplaninfos gibt es im Internet unter 2 © Rheinland-Pfalz Tourismus www.vrt-info.de, in der VRT-Fahrplan-App oder bei den Entdeckerfahrplan GmbH, Dominik Ketz Ihre Freizeitziele an den schönsten Strecken im VRT Verkehrsunternehmen im VRT. -

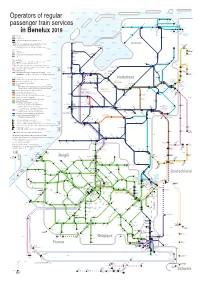

Operators of Regular Passenger Train Services in Benelux

S S S S S S S H H H H H H H S S S S S S S H H H H H H H H H H H H H H S S S S S S S d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S SHdS SHdS SHdS SHdS SHdS SHdS SHdS SHdS SHdS SHdS SHdS SHdS SHdS SHdS S SHdS SHdS SHdS SHdS SHdS SHdS SHdS H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H d d Hd d d Hd d d Hd d d Hd d H d Hd d d Hd d d Hd d d d d d d H H H H d H H H d d d d d d d d d d d d d H H H H H d H H S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S d S d S d S d S d S d S d S d S d S d S d S d S d S S d S d S d S d S d S d S d S d S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H S H S H S H S H S H S H S H S H S H S H S H S H S H S H S H S H S H S H S H S H S H d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H S H S H S H S H S H S H S H S H S H S H S H S H S H S H S H S H S H S H S H S H S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S d d d d d d d d d d d d d d S d d d d d d d H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d H d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d H H H H H H H H H H H H H H d H H H H H H H S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S S H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H -

5 1 2 1 4 6 8 3 3 5 7 9 10 7 8 9 10 11 12 11

Noch Fragen rund um C D E F G H I J Ihren Ausflug? Sie möchten wissen, ob es Einkehrmöglichkeiten auf der Strecke gibt oder welche Highlights Sie auf der Tour 1 1 erwarten? Diese Ansprechpartner helfen Ihnen gerne weiter: Ahrtal-Tourismus Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler e. V. Tel. 02641 / 91710 www.ahrtal.de Was kostet eine Fahrt? Eifel Tourismus GmbH Tel. 06551 / 96 56 0 Für Fahrten innerhalb der Verkehrsverbünde bieten sich im www.eifel.info 2 2 VRM die günstige Tageskarte oder Minigruppenkarte bzw. im VRT das TagesTicket Single oder TagesTicket Gruppe an. Bei Fahrten über die Verbundgrenze hinaus Bequem unterwegs mit den Hunsrück-Touristik GmbH Linie 844 gelten andere Tarife. Beispielsweise kommt bei Fahrten RadBus Ahr-Voreifel Tel. 06543 / 50 77 00 mit dem RadBus AhrVoreifel aus Rheinbach (NRW) in den RadBussen www.hunsruecktouristik.de Kreis Ahrweiler der VRSTarif zur Anwendung. Da die schönsten Radrouten nicht gleich vor der Haustür Jetzt unter ▶ In allen RadBussen kostet eine Fahrrad karte 3 Euro beginnen, bringen Sie jetzt insgesamt 21 RadBusse auf radbusse.de Mosellandtouristik GmbH je Fahrt für das Fahrrad eines Er wachsenen und 2 Euro teilweise neuen Streckenabschnitten zu den besten Tel. 06531 / 97 330 je Fahrt für das Fahrrad eines Kindes bis einschließlich Einstiegspunkten für Ihre Tour. Sparen Sie sich Ihre Energie buchen! www.visitmosel.de 14 Jahre. Im VulkanExpreß ist die Fahrrad mitnahme für die wirklich schönen Ausblicke entlang der Radstrecke kostenlos. und lassen Sie die RadBusse die teilweise beschwerliche Vulkan- Anfahrt übernehmen. Da sind zum Beispiel die Anstiege ▶ Die Plätze für Fahrräder in den RadBussen können RadBusse Naheland-Touristik GmbH 3 3 in der Eifel oder im Hunsrück, die ungeübten Radfahrern Expreß schnell vergeben sein. -

Fahrplänen Und Tickets Inhaltsverzeichnis

VOM 28.04. BIS 01.05.2018 IN DER REGION EIFEL-MOSEL-SAAR ZEITREISENDE BITTE EINSTEIGEN! WANN DAMPFT ES WO? ALLE INFOS ZU DEN LOKOMOTIVEN, FAHRPLÄNEN UND TICKETS INHALTSVERZEICHNIS Die Lokomotiven Seite 4–7 Rahmenprogramm rund ums Dampfspektakel Seite 8/9 TAUCHEN SIE EIN Tickets und Strecken Seite 10/11 IN DIE WELT DER DAMPFZÜGE Fahrpläne Seite 12–21 Anreise und Übernachtung Seite 22/23 Vielleicht erinnern Sie sich noch daran, als die großen, dampfenden Eisenbahnen die Schienen Deutschlands bevölkerten, und wollen dies noch einmal erleben? Oder vielleicht sind Sie noch so jung, dass Sie die Epoche der Dampfzüge nicht mehr miterlebten? Wie dem auch sei, 183 Jahre nach der ersten Eisenbahnfahrt in Deutschland können Sie die Faszination Dampf noch einmal in Rheinland-Pfalz und dem Saarland hautnah erleben. Beim Dampfspektakel 2018 kommen Nostalgiker genauso auf ihre Kosten wie Familien, denn neben den knapp 50 Fahrten verschiedener Schätzchen aus allen Epochen der Eisenbahngeschichte gibt es auch neben den Schienen viel zu erleben. Denn welche Kinderaugen leuchten nicht, wenn die Riesen aus längst vergangenen Zeiten laut und schnaufend in die Bahnhöfe einfahren? Zudem gibt es an verschiedenen Bahnhöfen zusätzliche Programmpunkte, IMPRESSUM die das Warten auf die nächste Fahrt zu kurzweiligen Fotos: kali9/istock (Vorder grund Titel), Brohltalbahn (S. 7 oben, Rückseite), Vergnügen werden lassen. K. Fischer (S. 8, 9 unten), Schulte-Fischedick/ TERRITORY CTR Gmbh (S. 9 oben), Informationen zum Dampfspektakel 2018, den Meinzahn/istock (S. 22), Veranstaltungen neben der Strecke, Fahrpläne und was M. Benz (alle anderen) Gestaltung: banana communication Sie noch wissen müssen, finden Sie auf den folgenden Stand: 03/2018 Seiten der Broschüre und kompakt im Internet unter Alle Angaben ohne Gewähr. -

Download Dertakt 1 03 VRT 01

Ausgabe 1/03 Mobil mit Bus und Bahn im Rheinland-Pfalz-Takt der Takt Ausgabe Region Trier » VRT Regional » Faszination Mittelalter » Der Takt macht die Musik Der Takt vor Ihrer Tür Burgen und Burgfeste in Rheinland-Pfalz-Tag Koblenz Rheinland-Pfalz 13.-15. Juni 2003 Seite 6 bis 8 Seite 3 Seite 4 www.der-takt.de Das Große Gewinnspiel auf Seite 3 Die andere Mosel Bahnwandern zwischen Konz und Perl Es gibt eine Mosel abseits der Klischees: ohne Und auch ohne spektakuläre Flussschleifen steile Schieferhänge, Burgenromantik und und malerische Fachwerkhäuser brauchen Ab in die Mitte! sommerliche Touristenströme. Hier, wo der sich die Winzerorte zwischen Konz und Perl Fluss die Grenze zwischen Deutschland und weder landschaftlich noch kulturell zu ver- Neue Haltepunkte in Ehrang-Ort und Wehr Luxemburg bildet und auch Frankreich gleich stecken. Was liegt da näher als ein gemütli- um die nächste Ecke liegt, scheint er langsa- cher Rad- oder Wanderausflug in die fast noch mer zu fließen, durch eine sanftere Land- unbekannte Region direkt vor der Haustür? schaft in milderem Licht. “Südliche Wein- Immer entlang der Mosel von Weinkeller zu Bessere Erreichbarkeit, bessere Verbin- 30-Minuten-Takt erreichbar sind. Und für Mosel” nennen die selbstbewussten Winzer Weinkeller – und vom nächsten Bahnhof aus dungen: Seit Ende 2002 ist der Trierer alle, die nach Ehrang wollen, sind die der Gegend ihre Region voll Stolz – und einfach wieder nach Hause! Stadtteil Ehrang durch den neuen Halte- Einkaufsmöglichkeiten in der Ortsmitte haben damit nicht nur geografisch Recht. Auf punkt Ehrang-Ort an das Schienennetz und das Marienkrankenhaus jetzt nur noch ihren leichten Muschelkalkböden wächst mitt- Fortsetzung auf Seite 7 angebunden.