Patterns of Settlement in Iceland: a Study in Prehistory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Þingvellir National Park

World Heritage Scanned Nomination File Name: 1152.pdf UNESCO Region: EUROPE AND NORTH AMERICA __________________________________________________________________________________________________ SITE NAME: Þingvellir National Park DATE OF INSCRIPTION: 7th July 2004 STATE PARTY: ICELAND CRITERIA: C (iii) (vi) CL DECISION OF THE WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE: Excerpt from the Report of the 28th Session of the World Heritage Committee Criterion (iii): The Althing and its hinterland, the Þingvellir National Park, represent, through the remains of the assembly ground, the booths for those who attended, and through landscape evidence of settlement extending back possibly to the time the assembly was established, a unique reflection of mediaeval Norse/Germanic culture and one that persisted in essence from its foundation in 980 AD until the 18th century. Criterion (vi): Pride in the strong association of the Althing to mediaeval Germanic/Norse governance, known through the 12th century Icelandic sagas, and reinforced during the fight for independence in the 19th century, have, together with the powerful natural setting of the assembly grounds, given the site iconic status as a shrine for the national. BRIEF DESCRIPTIONS Þingvellir (Thingvellir) is the National Park where the Althing - an open-air assembly, which represented the whole of Iceland - was established in 930 and continued to meet until 1798. Over two weeks a year, the assembly set laws - seen as a covenant between free men - and settled disputes. The Althing has deep historical and symbolic associations for the people of Iceland. Located on an active volcanic site, the property includes the Þingvellir National Park and the remains of the Althing itself: fragments of around 50 booths built of turf and stone. -

Early Religious Practice in Norse Greenland

Hugvísindasvið Early Religious Practice in Norse Greenland: th From the Period of Settlement to the 12 Century Ritgerð til M.A.-prófs Andrew Umbrich September 2012 U m b r i c h | 2 Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindasvið Medieval Icelandic Studies Early Religious Practice in Norse Greenland: th From the Period of Settlement to the 12 Century Ritgerð til M.A.-prófs Andrew Umbrich Kt.: 130388-4269 Leiðbeinandi: Gísli Sigurðsson September 2012 U m b r i c h | 3 Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 5 1.1 Scholarly Works and Sources Used in This Study ...................................................... 8 1.2 Inherent Problems with This Study: Written Sources and Archaeology .................... 9 1.3 Origin of Greenland Settlers and Greenlandic Law .................................................. 10 2.0 Historiography ................................................................................................................. 12 2.1 Lesley Abrams’ Early Religious Practice in the Greenland Settlement.................... 12 2.2 Jonathan Grove’s The Place of Greenland in Medieval Icelandic Saga Narratives.. 14 2.3 Gísli Sigurðsson’s Greenland in the Sagas of Icelanders: What Did the Writers Know - And How Did They Know It? and The Medieval Icelandic Saga and Oral Tradition: A Discourse on Method....................................................................................... 15 2.4 Conclusion ................................................................................................................ -

A B ©Lonely Planet Publications Pty

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd 358 architecture 19, 316 Grímsey 202 Arctic Fox Center 171 Heimaey Arctic Fox Research Station 171 Hrísey 201 Arctic foxes 35, 37, 171, 276, 311, 36 Ingólfshöfði 276 Arctic Henge 234-5 Krýsuvíkurberg 94 Arctic terns 312 Látrabjarg 162 Ari the Learned 303, 323 Mývatn region 222-3 Arnarson, Ingólfur 46 Papey 261 Arnarstapi 153-4 Reykjavík 52 Arnarvatnsheiði 142 Sandgerði 93 Árnes (Norðurfjörður) 178 Skálanes 255 Árnes (Þjórsárdalur) 101-2 Skrúður 259 Árskógsströnd 201 Snæfellsjökull National Park 152 100 Crater Park 93 arts 315-20 Stykkishólmur 143 101 Reykjavík 316, 318 Ásatrú 324-5 Viðey 80 4WD tours 227, 236, 242, 282 Ásbyrgi 232-3 Bjarkalundur 159 Áshöfði 233 Bjarnarfjörður 177 Bjarnarflag 223-4 A Askja 217, 294-5, 293 Bjarnarhöfn 148-9 accommodation 20, 332-5, see also Askja Way 292-5 individual locations Ásmundarsafn 50 Björk 317 activities 22, 24, 32-8, see also ATMs 339 Bláa Kirkjan 251 individual activities aurora borealis 9, 25, 37, 59, 9, 179 Bláfjöll 57 Aðalból 247 Austurengjar 94 Blue Lagoon 6, 58, 88-9, 6-7 Age of Settlement 301 Austurvöllur 49 Blönduós 191-2 air travel 344, 345 boat tours, see also kayaking Akranes 135, 138 Heimaey 131-2 B Akureyri 203-15, Hvítárvatn 288-9 204-5 Baðstofa 153 accommodation 209-11 Ísafjörður 167-8 Bakkagerði 247-50 activities 207-9 Jökulsárlón 277 Bárðarlaug 153 drinking 212-13 Stykkishólmur 144-5 Básendar 93 emergency services 213 boat travel 345, 346 beaches entertainment 213 boating 32-3 Breiðavík 162 festivals 209 Bolungarvík 170 Hvallátur 162 food 211-12 -

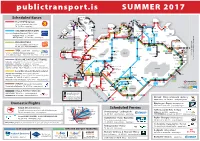

Public Transport Summer 2017 in English

publictransport.is SUMMER 2017 Hornstrandir Area Scheduled Buses Hornvík Bolungarvík Grímsey The STRÆTÓ System Kópasker Raufarhöfn Hnífsdalur Dranga- Reykjar- Siglufjörður jökull Flatey This is the main public bus system Ísafjörður Vigur fjörður 78 641 Drangey Tel. 540 2700 - www.bus.is Suðureyri Súðavík Hrísey Norður- Ólafs- 79 Flateyri fjörður Skagaströnd Reykir Hofsós fjörður Ásbyrgi 650 Húsavík Þórshöfn Þingeyri 84 85 Dalvík Reykjanes Gjögur Hólar ICELAND ON YOUR OWN Bíldudalur Crossroads Sauðárkrókur Árskógssandur Aðaldalsvegur Hljóðaklettar & Hauganes Operated by Reykjavik Excursions & SBA-Norðurleið Tálknafjörður Skriðuland 650 641 85 Dettifoss Patreksfjörður Islands) (Faroe Tórshavn LINE to SMYRIL Reykjavik Office: Tel. 580 5400 Örlygshöfn 59 Hólmavík 661 Vopnafjörður Blönduós 84 Akureyri FnjóskárbrúNorðaustur- Brjánslækur vegur 79 Akureyri Office: Tel. 550 0700 - www.ioyo.is Fosshóll Krafla Látrabjarg Rauðasandur Hvammstangi Varmahlíð 57 60 661 Víðigerði 56 79 5 Svartá and Hirtshals (Denmark) 83 Króks- 62 641 Einarsstaðaskáli Jökulsá fjarðarnes Hvammstangavegur Laugar Vopnafjörður Borgarfjörður eystri ICELAND BY BUS Flatey Crossroads 62 á Fjöllum Crossroads Skriðuland 610 Skjöldólfs- Operated by Sterna & SBA-Norðurleið staðir Skútu- Fella- Seyðis- Tel. 551 1166 - www.icelandbybus.is Staðarskáli Mývatn Dettifoss Búðardalur staðir Crossroads bær fjörður r Hveravellir Aldeyjarfoss 650 661 k fjörður 57 60 3 issandu ví r Stykkishólmur 14 17 Norðfjörður TREX Tel. 587 6000 - www.trex.is Hell Rif Ólafs 82 58 59 1 Grunda Kerlingar- 62 62 56 1 Bifröst fjöll ASK 1 Services to Þórsmörk (Básar and Langidalur) Hofsjökull Eskifjörður Vatnaleið Herðubreiðarlindir Egilsstaðir Snæfells- Baula Langjökull Hvítárnes and Landmannalaugar. Summer schedule 15 June - 24 Sept. 2017 jökull Crossroads Reyðar- fjörður 2 Vegamót Reykholt Nýidalur Askja 82 Arnar- 58 81 Kleppjárnsreykir 6 Gullfoss 14 Fáskrúðsfjörður stapi 17 MAIN LINES IN THE WESTFJORDS Borgarnes Hvanneyri Laugarvatn Geysir Stöðvarfjörður Ísafjörður – Hólmavík: Tel. -

Social-Ecological Resilience in the Viking-Age to Early-Medieval Faroe Islands

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2015 Social-Ecological Resilience in the Viking-Age to Early-Medieval Faroe Islands Seth Brewington Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/870 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] SOCIAL-ECOLOGICAL RESILIENCE IN THE VIKING-AGE TO EARLY-MEDIEVAL FAROE ISLANDS by SETH D. BREWINGTON A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Anthropology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2015 © 2015 SETH D. BREWINGTON All Rights Reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Anthropology to satisfy the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _Thomas H. McGovern__________________________________ ____________________ _____________________________________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee _Gerald Creed_________________________________________ ____________________ _____________________________________________________ Date Executive Officer _Andrew J. Dugmore____________________________________ _Sophia Perdikaris______________________________________ _George Hambrecht_____________________________________ -

The First Settlers of Iceland: an Isotopic Approach to Colonisation

The first settlers of Iceland: an isotopic approach to colonisation T. Douglas Price1 & Hildur Gestsdottir´ 2 The colonisation of the North Atlantic from the eighth century AD was the earliest expansion of European populations to the west. Norse and Celtic voyagers are recorded as reaching and settling in Iceland, Greenland and easternmost North America between c. AD 750 and 1000, but the date of these events and the homeland of the colonists are subjects of some debate. In this project, the birthplaces of 90 early burials from Iceland were sought using strontium isotope analysis. At least nine, and probably thirteen, of these individuals can be distinguished as migrants to Iceland from other places. In addition, there are clear differences to be seen in the diets of the local Icelandic peoples, ranging from largely terrestrial to largely marine consumption. Keywords: Iceland, colonisation, settlement, isotopes, strontium, human migration, enamel Introduction An extraordinary series of events began in the North Sea and North Atlantic region around the eighth century AD. Norse raiders and settlers from Scandinavia, better known as the Vikings, began expanding to the west, settling in the British Isles and Ireland, including the smaller groups of islands, the Orkneys, Shetlands, Hebrides and the Isle of Man. Stepping across the North Atlantic, Norse colonists reached the Faeroe Islands by around AD 825, Iceland by around AD 875 and Greenland by around AD 895 (Figure 1). Both Iceland and the Faeroe Islands were uninhabited at the time of the Norse colonisation. The Norse also settled briefly in North America at L’Anse aux Meadows, Newfoundland, around AD 1000 (Jones 1986; Wallace 1991). -

ICELAND 2006 Geodynamics Field Trip May 30 – June 8, 2006

ICELAND 2006 Geodynamics Field Trip May 30 – June 8, 2006 Massachusetts Institute of Technology/ Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution Joint Program in Oceanography This field trip guide was compiled by Karen L. Bice using information from Bryndís Brandsdóttir, Richard S. Williams, Helgi Torfason, Helgi Bjornsson, Oddur Sigurðsson, the Iceland Tourist Board and World W. Web Maps from Thordarson and Hoskuldsson, 2002, Iceland (Classic Geology in Europe 3), Terra Publishing, UK. Logistical genius: Andrew T. Daly Field trip participants: Mark Behn, Karen Bice, Roger Buck, Andrew Daly, Henry Dick, Hans Schouten, Martha Buckley, James Elsenbeck, Pilar Estrada, Fern Gibbons, Trish Gregg, Sharon Hoffmann, Matt Jackson, Michael Krawczynski, Christopher Linder, Johan Lissenberg, Andrea Llenos, Rowena Lohman, Luc Mehl, Christian Miller, Ran Qin, Emily Roland, Casey Saenger, Rachel Stanley, Peter Sugimura, and Christopher Waters The Geodynamics Program is co-sponsored by Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution’s Academic Programs Office and Deep Ocean Exploration Institute. TUESDAY May 30 Estimated driving (km) Meet at Logan Airport, Icelandair ticket counter @ 7:00 PM (80 km ≈ 50 mi) Depart BOS 9:30 PM Icelandair flight Day 1 - WEDNESDAY May 31 Arrive Keflavík International Airport 6:30 AM (flight duration 5 hours) Pick up 2 vans, 2 trailers (Budget) Free day in Reykjavík Night @ Laugardalur campground, Reykjavík Dinner: on own in town Day 2 - THURSDAY June 1 270 Late start due to trailer problems (2 hrs @ AVIS) To Þingvellir N.P., then north to Hvalfjörður fjord, stop at Skorradalsvatn Night @ Sæberg Hostel (1 km. off Rte 1 in Hrútafjörður, west side of road) Tel. 354-4510015 Fax. 354-4510034 [email protected] Dinner: mexican-style chicken (Rachel, Trish, Chris) Day 3 - FRIDAY June 2 320 To Lake Myvatn Lunch stop in Akureyri, stop at Godafoss, stop at Skutustadir pseudocraters Night @ Ferdathjonustan Bjarg campsite, Reykjahlid, on shore of Lake Myvatn Tel. -

Reykjavík Unesco City of Literature

Reykjavík unesco City of Literature Reykjavík unesco City of Literature Reykjavík unesco City of Literature Reykjavík City of Steering Committee Fridbjörg Ingimarsdóttir Submission writers: Literature submission Svanhildur Konrádsdóttir Director Audur Rán Thorgeirsdóttir, (Committee Chair) Hagthenkir – Kristín Vidarsdóttir Audur Rán Thorgeirsdóttir Director Association of Writers (point person) Reykjavík City of Non-Fiction and Literature Trail: Project Manager Department of Culture Educational Material Reykjavík City Library; Reykjavík City and Tourism Kristín Vidarsdóttir and Department of Culture Esther Ýr Thorvaldsdóttir Úlfhildur Dagsdóttir and Tourism Signý Pálsdóttir Executive Director Tel: (354) 590 1524 Head of Cultural Office Nýhil Publishing Project Coordinator: [email protected] Reykjavík City Svanhildur Konradsdóttir audur.ran.thorgeirsdottir Department of Culture Gudrún Dís Jónatansdóttir @reykjavík.is and Tourism Director Translator: Gerduberg Culture Centre Helga Soffía Einarsdóttir Kristín Vidarsdóttir Anna Torfadóttir (point person) City Librarian Gudrún Nordal Date of submission: Project Manager/Editor Reykjavík City Library Director January 2011 Reykjavík City The Árni Magnússon Institute Department of Culture and Audur Árný Stefánsdóttir for Icelandic Studies Photography: Tourism/Reykjavík City Library Head of Primary and Lower Cover and chapter dividers Tel: (354) 411 6123/ (354) 590 1524 Secondary Schools Halldór Gudmundsson Raphael Pinho [email protected] Reykjavík City Director [email protected] -

Iceland's External Affairs in the Middle Ages: the Shelter of Norwegian Sea

FRÆÐIGREINAR STJÓRNMÁL & STJÓRNSÝSLA Iceland’s external affairs in the Middle Ages: The shelter of Norwegian sea power Baldur Þórhallsson , Professor of Political Science, University of Iceland Abstract According to the international relations literature, small countries need to form an alliance with larger neighbours in order to defend themselves and be economically sustainable. This paper applies the assumption that small states need economic and political shelter in order to prosper, economically and politically, to the case of Iceland, in an historical context. It analyses whether or not Iceland, as a small entity/country in the Middle Ages (from the Settle ment in the 9 th and 10 th centuries until the late 14 th century) enjoyed political and economic shelter provided by its neighbouring states. Admitting that societies were generally much more self-sufficient in the Middle Ages than in our times, the paper argues that Iceland enjoyed essential economic shelter from Norwegian sea power, particularly as regards its role in securing external market access. On the other hand, the transfer of formal political authority from Iceland to the Norwegian crown was the political price paid for this shelter, though the Icelandic domestic elite, at the time, may have regarded it as a political cover. The country’s peripheral location shielded it both from military attacks from outsiders and the king’s day-to-day interference in domestic affairs. That said, the island was not at all unexposed to political and social developments in the British Isles and on the European continent, e.g. as regards the conversion to Christianity and the formation of dynastic and larger states. -

Publictransport.Is 2020 Personen

Öffentliche Linienbusse STRÆTÓ (ganzjährig) Dies ist das öffentliche Busnetz in Island 2020 publictransport.is Tel. 540 2700 - www.bus.is SVAUST Bussystem der Ostfjorde (ganzjährig) Hornstrandir-Gebiet Tourist Info in Egilsstaðir: Tel. 471 2320 - www.svaust.is Hornvík Bolungarvík Grímsey Tourist Info in Seyðisfjörður: Tel. 472 1551 - www.visitseydisfjordur.com Raufarhöfn Hnífsdalur Dranga- Reykjar- Siglufjörður Ísafjörður jökull Kópasker Vigur fjörður 78 Flatey Lokale Busse in West-Island (ganzjährig) Suðureyri Drangey Hrísey 79 Súðavík Norður- Ólafs- Bolungarvík - Ísafjörður (Flughafen): Tel. 893 8355 - www.bolungarvik.is A fjörður Húsavík Flateyri fjörður Skagaströnd Hofsós Ásbyrgi Þórshöfn Ísafjörður – Suðureyri – Flateyri – Þingeyri: Tel. 893 6356 - www.isafjordur.is Þingeyri 84 Dalvík Heydalur Gjögur Hólar Grenivík Kreuzung Patreksfjörður - Bíldudalur: Tel. 456 5006 & 848 9614 - www.vesturbyggd.is Bíldudalur Sauðárkrókur Árskógssandur Hljóðaklettar & Hauganes Aðaldalsvegur Patreksfjörður - Bíldudalur Flughafen: Tel. 893 0809 & 893 2636 - vesturbyggd.is Tálknafjörður Dynjandi Reykjanes Drangsnes ú r- Grímsey und Hirtshals (Dänemark) (Färöer) Tórshavn Skriðuland br tu Hellissandur - Rif - Ólafsvík: Tel. 433 6900 & 892 4327 - www.snb.is Patreksfjörður Flókalundur ár s ur sk au eg Dettifoss ó rð v B A 59 Hólmavík nj o Vopnafjörður Westfjords Tourist Information: Tel. 450 8060 - www.westfjords.is Blönduós 84 Akureyri F N Brjánslækur Látrabjarg Rauðasandur B Hvammstangi Víðigerði Varmahlíð 57 78 56 79 Krafla 5 nach LINE - Fähre SMYRIL Svartá -

Medieval Monasticism in Iceland and Norse Greenland

religions Article Medieval Monasticism in Iceland and Norse Greenland Steinunn Kristjánsdóttir Department of Archaeology, University of Iceland, 101 Reykjavík, Iceland; [email protected] Abstract: The aim of this paper is to provide an overview of the monastic houses operated on the northernmost periphery of Roman Catholic Europe during the Middle Ages. The intention is to debunk the long-held theory of Iceland and Norse Greenland’s supposed isolation from the rest of the world, as it is clear that medieval monasticism reached both of these societies, just as it reached their counterparts elsewhere in the North Atlantic. During the Middle Ages, fourteen monastic houses were opened in Iceland and two in Norse Greenland, all following the Benedictine or Augustinian Orders. Keywords: Iceland; Norse Greenland; monasticism; Benedictine Order; Augustine Order The aim of this article is to provide an overview of the medieval monastic houses operating in the northernmost dioceses of the Roman Catholic Church: Iceland and Norse Greenland. At the same time, it questions the supposed isolation of these societies from the rest of the Continent. Research on activities in Iceland and Greenland shows that the transnational movement of monasticism reached these two countries as it reached other parts of Northern Europe. Fourteen monastic houses were established in Iceland and two in Norse Greenland during the Middle Ages. Two of the monastic houses in Iceland and one in Norse Greenland were nunneries, whereas the others were monasteries. Five of the monasteries established in Iceland were short lived, while the other nine operated for Citation: Kristjánsdóttir, Steinunn. centuries. All were closed due to the Reformation around the mid-sixteenth century. -

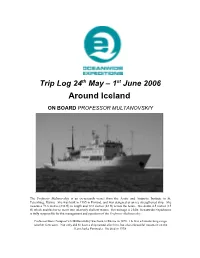

Around Iceland

Trip Log 24th May – 1st June 2006 Around Iceland ON BOARD PROFESSOR MULTANOVSKIY The Professor Multanovskiy is an ex-research vessel from the Arctic and Antarctic Institute in St. Petersburg, Russia. She was built in 1985 in Finland, and was designed as an ice strengthened ship. She measures 71.6 metres (236 ft) in length and 12.8 metres (42 ft) across the beam. She draws 4.5 metres (15 ft) which enables her to move into relatively shallow waters. Her tonnage is 2140t. Oceanwide Expeditions is fully responsible for the management and operation of the Professor Multanovskiy. Professor Boris Pompeevich Multanovskiy was born in Russia in 1876. He was a famous long-range weather forecaster. Not only did he have a ship named after him, but also a beautiful mountain on the Kamchatka Peninsula. He died in 1938. With Captain Igor Stetsun and his crew of 19 from St. Petersburg, Russia Expedition Leader: Rolf Stange (Geographer), Germany Guide/Lecturer: Dagný Indriđadóttir (Folklorist), Iceland Guide/Lecturer: Ian Stone (Historian), Isle of Man Purser: Juliette Corssen, Germany Chefs: Jocelyn Wilson, New Zealand & Gerd Brenner, Germany Doctor: Johannes Schön, Germany 24th May - Embarkation in Keflavík, Faxaflói Bay 4 pm: Position: 64º00N: 22º36W, partly sunny, strong wind. Most of us arrived in due time for embarkation at 4 pm. on a blustery day in Iceland. Many anxious eyes were cast seawards but were consoled by the remarks that we overheard that the weather seemed to be improving! Our Expedition Leader, Rolf Stange from Germany welcomed us on board the Professor Multanovskiy and introduced the staff to us.