A Global Review of Protected Area Budgets and Staff Blank Page WCMC Biodiversity Series No.10

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Development of National Parks and Protected Areas Around the World

The Development of National Parks and Protected Areas around the World Masaaki Yui October 2014 Natural Environment Coexistence Technology Association JAPAN Contents ● Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………..1 ● The world’s first natural protected area…………………………………………………………...1 ● The introduction and development of national parks in other countries………………………….2 ● Trends in establishing national parks and recent changes………………………………………….5 ● Nature protection areas established in each country……………………………………………...6 ● Countries with natural protected areas and the period of their establishment……………………8 ● Global trends in establishing natural protected areas: the dawn of natural protected areas………...9 ● Development of natural protection areas…………………………………………………………..10 ● Features of nature protection areas by region…………………………………………….………..13 ● The impact of international conventions and conferences on nature protection…………………..17 ● Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………………………19 ● References…………………………………………………………………………………………20 Table 1 Establishment year of the first national park by country.......................................................4 Table 2 Examples of natural protected areas.......................................................................................7 Table 3 Period in which countries established their first natural protected area..................................8 Table 4 Global trends in establishing natural protected areas: the establishment of the first protected area by type and region…………………………..11 Table 5 Number -

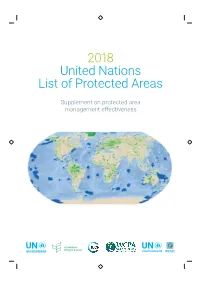

2018 United Nations List of Protected Areas

2018 United Nations List of Protected Areas Supplement on protected area management effectiveness Aires protégéesLorem terrestres ipsum Aires protégées marines et côtières Citation: UNEP-WCMC (2018). 2018 United Nations List of Protected Areas. Supplement on protected area management effectiveness. UNEP-WCMC: Cambridge, UK. Copyright 2018 United Nations Environment Programme. ISBN: 978-92-807-3717-2 Job No: DEP/2197/CA The UN Environment World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP-WCMC) is the specialist biodiversity Centre of UN Environment, the world’s foremost intergovernmental environmental organisation. The Centre has been in operation for almost 40 years, combining scientific research with practical policy advice. This publication may be reproduced for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission, provided acknowledgement to the source is made. Reuse of any figures is subject to permission from the original rights holders. No use of this publication may be made for resale or any other commercial purpose without permission in writing from UN Environment. Applications for permission, with a statement of purpose and extent of reproduction, should be sent to the Director, UNEP-WCMC, 219 Huntingdon Road, Cambridge, CB30DL, United Kingdom. The contents of this report do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of UN Environment, contributory organizations or editors. The designations employed and the presentations of material in this report do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UN Environment or contributory organizations, editors or publishers concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city area or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries or the designation of its name, frontiers or boundaries. -

* Council of * Conseil De L'

Naturona * COUNCIL OF * CONSEIL DE L’ Naturopa N°72-1993 : : Editorial V. Bossevski 3 What future for our mountains? W. Bätzing 4 Managing this vulnerable environment P. Messerli 6 The Rhodope Mountains. Jewel of Bulgaria J. Danchev 8 * * * Mountainous perspectives. Lessons from history E. Lichtenberger 9 CENTRE An ecological approach P. Stoll 11 NATUROPA Living nature P. Ozenda 12 The Alpine Convention U. Tödter 14 In Italy F. Bartaletti 15 A blessing in disguise? A. Gosar 20 Editorial Teberda A.M. Amirkhanov, N. N. Polivanova 22 he Balkans represent a vast mountai and species endemic to the Balkans such as altitude run to 2,000 m. There are between nous universe with a natural environ the Pinus peuce. Coniferous bushes and 1,700 and 1,850 higher plant species and Delights in the heights H. Haid 23 T ment very similar to that of the Alps, Siberian junipers grow above the forests, between 170 and 200 species of vertebrates. the Appenines and the Carpathians, but with rocky Alpine meadows dotted with small Out of the 50 protected areas in Bulgaria on Naturopa is published in English, Wise use of natural resources F. Sieren, P. F. Sieben 24 which also has its own special features. The glaciers at the summits and peaks. the United Nations’ list of national parks, 40 French, German, Italian, Spanish and proximity of Asia has enriched its fauna and are in the mountains. Portuguese by the Centre Naturopa of the Mountaineering: protection first J. Klenner 26 flora, but it is the species and populations Mountain conservation in Bulgaria dates Council of Éurope, F-67075 Strasbourg typical of the Balkans alone that make it from the last century. -

1993 United Nations List of National Parks and Protected Areas

1993 United Nations List of National Parks and Protected Areas Liste des Nations Unies des Pares nationaux et des Aires protegees 1993 Lista de las Naciones Unidas de Parques Nacionales y Areas Protegidas 1993 Prepared by the World Conservation Monitoring Centre and the lUCN Commission on National Parks and Protected Areas lUCN UNEP WORLD CCMSERVATION The Woild Conservation Union MONITOP,|NG CENTRE Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from UNEP-WCMC, Cambridge http://www.archive.org/details/1993unitednation93worl 1993 United Nations List of National Parks and Protected Areas Liste des Nations Unies des Pares nationaux et des Aires protegees 1993 Lista de las Naciones Unidas de Parques Nacionales y Areas Protegidas 1993 lUCN - The World Conservation Union Founded in 1948, lUCN - The World Conservation Union brings together States, government agencies and a diverse range of non-governmental organiaztions in a unique world partnership: more than 800 members in all, spread across 126 countries. The Union seeks to work with its members to achieve development that is sustainable and that provides a lasting improvement in the quality of life for people all over the world. UICN - Union mondiale pour la nature Fondee en 1948, 1'UICN - Union mondiale pour la nature reunit des Etats, des organismes publics et un large eventail d'organisations non gouvemementales en une association mondiale unique: en tout, plus de 800 membres dans 1 26 pays. L'Union cherche a oeuvrer, en collaboration avec ses membres, a I'avenement d'un developpement qui soit durable et ameliore de maniens permanente la qualite de vie de I'humanite tout entiere. -

1982 United Nations List of National Parks and Protected

:2 I 1982 United Nations List of National Parks and Protected Areas List des Nations Unies des Parcs Nationaux et des Aires Protégées 1982 Prepared by the lUCN Commission on National Parks and Protected Areas Préparée par la Commission des Parcs Nationaux et des Aires Protégées de 1 'UICN UNEP/PNUE Published with the financial assistance of Unesco and in cooperation with UNEP as a contributor to the Global Environment Monitoring System Publiée avec l'aide financière de l 'Unesco et travaillant dans un but commun avec PNUE; une contribution au système mondiale de surveillance continuée 1 'environment INTERNATIONAL UNION FOR CONSERVATION OF NATURE AND NATURAL RESOURCES UNION INTERNATIONALE POUR LA CONSERVATION DE LA NATURE ET DE SES RESSOURCES 1196 Gland, Suisse 1982 ) © 1982 lUCN Unesco subvention 1981 - 1983 DG/7 . 6. 2/SUB . 14 (SSC ISBN 2-88032-409-2 Printed in Great Britain by Unwin Brothers Ltd., The Gresham Press, Old Woking, Surrey 1982 United Nations List of National Parks and Protected Areas List des Nations Unies des Parcs Nationaux et des Aires Protégées 1982 Prepared by the lUCN Commission on National Parks and Protected Areas Préparée par la Commission des Parcs Nationaux et des Aires Protégées de 1 'UICN Published with the financial assistance of Unesco and in cooperation with UNEP as a contributon to the Global Environment Monitoring System Publiée avec l'aide financière de 1 'Unesco et travaillant dans un but commun avec PNUE; une contribution au système mondiale de surveillance continuée 1 'environment INTERNATIONAL UNION -

Planning National Parks for Eco-Development - Methods and Cases from Latin America

Planning National parks for Eco-development - Methods and Cases from Latin America Volumes I & II Written by: Kenton R. Miller, Ph. D. School of Natural Resources The University of Michigan Ann Arbor, Michigan USA Peace Corps Information, Collection & Exchange Reprint R073 March 1989 Reprinted with permission of Kenton R. Miller, Ph. D. Fundación pare la Ecologia y pare la Protección del Medio Ambiente Madrid, Spain Dedication... to the park managers and rangers who carry the custodianship of their nation's natural and cultural heritage, to manage them for the benefit of present and future generations... First Printing - 1978 Second Printing - 1979 Third Printing - 1982 Bibliographic Information Miller, Kenton R. 1978. Planning National Parks for Ecodevelopment: Methods and Cases from Latin America. Center for Strategic Wildland Management Studies, The School of Natural Resources, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA. 625+ pages. (manuscript) Copies of the English language manuscript may be purchased from the following organization: Center for Strategic Wildland Management Studies School of Natural Resources The University of Michigan Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109 USA Miller, Kenton R. 1980. Planificación de Parques Nacionales para el Ecodesarrollo en Latiroamérica. Fundación para la Ecologia y para la Protección del Medio Ambiente, Madrid, Spain. 500 páginas. ISBN No. 84-300-2247-3 Copies of the Spanish language publication may be purchased from the following organization: Center for Strategic Wildland Management Studies School of Natural Resources The University of Michigan Ann Arbor, MI 481C9 USA INFORMATION COLLECTION & EXCHANGE Peace Corps' Information Collection & Exchange (ICE) was established so that the strategies and technologies developed by Peace Corps Volunteers, their co-workers, and their counterparts could be made available to the wide range of development organizations and individual workers who might find them useful. -

The New Paradigm of Protected Areas

Adrian Phillips Turning Ideas on Their Head The New Paradigm For Protected Areas Introduction he ideas that this paper brings together will be individually familiar to resource managers, protected area planners and managers, and other conservation experts, but they may not have considered their combined Tsignificance. So its purpose is not so much to break new ground as to suggest that the changes that have occurred in our thinking and practice towards protected areas over the past 40 or so years amount to a revolution. But while the merits of many of these individual changes have been fiercely debated, their col- lective significance, which can be traced in the decisions of four world parks con- gresses, has largely gone unnoticed. Yet taken together they have produced a new paradigm for protected areas in the 21st century. Powerful forces have helped to bring about this new paradigm—and they will have an even greater influence on protected areas thinking and practice in future. Protected Areas •To be area-based concepts that A starting point is a definition of might be found anywhere; “protected area.” IUCN adopted this •To require specific measures (dedi- in 1994: cation, designation, regulation) for [An] area of land and/or sea especial- the purposes of biodiversity con- ly dedicated to the protection and servation (i.e., protection and maintenance of biological diversity, maintenance); and of natural and associated cultural resources, and managed through legal •To require management, delivered or other effective means (IUCN 1994). through legal or other effective means; and The Convention on Biological • By implication, to require that Diversity (CBD) uses a different defi- some kind of management authori- nition: ty is in place to secure conserva- [A] geographically defined area which is designated or regulated and man- tion. -

********************T***************************** * Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best That Can Be Made * from the Original Document

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 309 033 SE 050 658 AUTHOR Miller, Kenton R. TITLE Planning National Parks for Ecodevelopment. Methods and Cases from Latin America. Volumes 1 and 11. Reprint R073. INSTITUTION Peace Corps, Washington, DC. Information Collection and Exchange Div. PUB DATE Mar 89 NOTE 680p.; Volume II was originally published in 1978. Pages with small or broken print, and some drawings, may not reproduce well. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Use Guides (For Teachers) (052) EDRS PRICE MF04/PC28 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Ecology; Environmental Education; *Facility Planning; Foreign Countries; *Land Use; *Natural Resources; *Parks; Planning; *Science Careers; Science Facilities; Scientific Personnel IDENTIFIERS *Latin America; Peace Corps ABSTRACT This book deals with methods for planning national parks to enable them to provide the greatest benefit to human activity. Chapters included are:(1) "A Conceptual Framework for the Management of Wildland Resources"; (2) "The Growth and Development of National Parks in Latin America";(3) "Planning National Parks for Ecodevelopment in Latin America";(4) "The Evolution of National Park Planning in Latin America";(5) "A Practical Method for Park Planning"; (6)"A Practical Method for Planning National Park Systems"; (7)"The Formulation of a Strategy Plan";(8) "Human and Institutional Capacity to Manage National Parks"; (9) "Some Guidelines from Park Management Experience in Africa";(10) "Major Problems Facing National Park Management in Latin America"; (11) "International Cooperation and Assistance in National Park Management"; and (12) "Strategy for Regional and Global Cooperation." Appendices are inserted in each chapter, and a 22-page index has been supplied. (YP) *****************************************t***************************** * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made * from the original document. -

1973 United Nations List National Parks Equivalent Reserves

IUCN Publications New Series No. 27 1973 United Nations List of National Parks and Equivalent Reserves Prepared by the Secretariat of IUCN with the advice and guidance of the IUCN International Commission on National Parks 19 4 8 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources 1110 Morges, Switzerland 1973 The International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) is an independent international body, formed in 1948, which has its headquarters in Morges, Switzerland. It is a Union of sovereign states, govern- ment agencies and non-governmental organizations concerned with the initia- tion and promotion of scientifically-based action that will ensure perpetuation of the living world - man's natural environment - and the natural resources on which all living things depend, not only for their intrinsic cultural or scientific values but also for the long-term economic and social welfare of mankind. This objective can be achieved through active conservation programmes for the wise use of natural resources based on scientific principles. IUCN believes that its aims can be achieved most effectively by international effort in cooperation with other international agencies, such as Unesco and FAO. The World Wildlife Fund (WWF) is an international charitable organization dedicated to saving the world's wildlife and wild places, carrying out the wide variety of programmes and actions that this entails. WWF was established in 1961 under Swiss law, with headquarters also in Morges. Since 1961, IUCN has enjoyed a symbiotic relationship with its sister organiza- tion, the World Wildlife Fund, with which it works closely throughout the world on projects of mutual interest. -

2018 United Nations List of Protected Areas

2018 United Nations List of Protected Areas Supplement on protected area management effectiveness Aires protégéesLorem terrestres ipsum Aires protégées marines et côtières ISBN: 978-92-807-3717-2 Job No: DEP/2197/CA Citation: UNEP-WCMC (2018). 2018 United Nations List of Protected Areas. Supplement on protected area management effectiveness. UNEP-WCMC: Cambridge, UK. Copyright 2018 United Nations Environment Programme. ISBN: 978-92-807-3717-2 Job No: DEP/2197/CA The UN Environment World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP-WCMC) is the specialist biodiversity Centre of UN Environment, the world’s foremost intergovernmental environmental organisation. The Centre has been in TUJWFYNTSKTWFQRTXY^JFWXHTRGNSNSLXHNJSYNܪHWJXJFWHM\NYMUWFHYNHFQ policy advice. 9MNXUZGQNHFYNTSRF^GJWJUWTIZHJIKTWJIZHFYNTSFQTWSTSUWTܪYUZWUTXJX without special permission, provided acknowledgement to the source is made. 7JZXJTKFS^ܪLZWJXNXXZGOJHYYTUJWRNXXNTSKWTRYMJTWNLNSFQWNLMYXMTQIJWX No use of this publication may be made for resale or any other commercial purpose without permission in writing from UN Environment. Applications for permission, with a statement of purpose and extent of reproduction, should be sent to the Director, UNEP-WCMC, 219 Huntingdon Road, Cambridge, CB30DL, United Kingdom. 9MJHTSYJSYXTKYMNXWJUTWYITSTYSJHJXXFWNQ^WJܫJHYYMJ[NJ\XTWUTQNHNJXTK:3 Environment, contributory organizations or editors. The designations employed and the presentations of material in this report do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UN Environment -

Some Data Related to Costs and Benefits of National Parks in Latin America"

CENTRO AGRONOMICO TROPICAL DE INVESTIGACION Y ENSENANZA CATIE Departamento de Ciencias Forestales "SOME DATA RELATED TO COSTS AND BENEFITS OF NATIONAL PARKS IN LATIN AMERICA" Arne Dalfelt TUrrialba. Costa Rica 1976 INDEX Page I.. Acknowledgements .. ~ .. .. .. .. .•.......... .. .. .. .. .. .... .... .. ... .... .. .. .. .. .. .. 1 II . Introduction to study 2 III. Statistical base and collection of data ••.••••••••••••••••• 3 A. GENERAL INTRODUCTION TO THE LATIN AHERICAII NATIONAL PARK SYSTEM 1. Background.. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. •.• .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 4 2.. Geographic distribution 4 3. Costs and benefits 4 4.. National parks and reserves I .. .. .. .. .. • .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 7 B. THE COHPREHENSIVE COSTS OF ESTABLISHING AND OPERATING NATIONAL PARKS AND Rr.SERVES IN LATIN AHERICA 1. Human resources ..................... I .. 10 2. Salary costs '.. ' .. 12 3. Technical capacity of personnel .........•••••.•...•..... 14 4. Non-capital and capital costs . 14 5. 'I'he land ar-ea input .............................•....... 17 6. Land use conflicts ..........•................•.......... 19 C. THE COMPRENSIVr; BENEFITS OF IlATIONP,L PARKS OR EQUIVALENT RESERVES III LATIN AHERICA 1. Ecosystem protection •.•.•.••••••••••.•..•••••••••••••••• 21 2. Fauna ....................................•...••.......... 22 3. Flora................................................... 25 4. Ecological monit (j:"'inC 28 5. Research and traininc; .••.•..•••••..•.•••.•..•••.•••••.•. 28 -

State of the World's Protected Areas at the End of the Twentieth Century

Paper presented at lUCN World Commission on Protected Areas Symposium on "Protected Areas in the 21' Century: From Islands to Networks" Albany, Australia, 24-29 November 1997 STATE OF THE WORLDS PROTECTED AREAS AT THE END OF THE TWENTIETH CENTURY Michael J.B. Green and James Paine World Conservation Monitoring Centre, Cambridge, UK 1. INTRODUCTION Protected areas are widely held to be among the most effective means of conserving biological diversity in situ (McNeely and Miller, 1984; MacKinnon et ai, 1986; Leader- Williams et al, 1990). A considerable amount of resources has been invested in their establishment over the last century or more, with the result that most countries have established or, at least, planned national systems of protected areas. The purpose of this paper is to examine the extent of the world's protected areas globally and regionally and to consider other options for its further strengthening and development during the twenty-first century. 1.1 What is a protected area? A protected area is defined by the lUCN World Commission on Protected Areas (lUCN, 1994) as: An area of land and/or sea especially dedicated to the protection and maintenance of biological diversity, and of natural and associated cultural resources, and managed through legal or other effective means. In practice, protected areas are managed for a wide variety of purposes which may include: scientific research, wilderness protection, preservation of species and ecosystems, maintenance of environmental services, protection of specific natural and cultural features, tourism and recreation, education, sustainable use of resources from natural ecosystems, and maintenance of cultural and traditional attributes.