The Case of Deepwater

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Department of Homeland Security U.S

DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY U.S. Naval Security Station, 3801 Nebraska Avenue, NW., Washington, DC 20393 phone 282–8000 TOM RIDGE, Secretary of Homeland Security; born on August 26, 1945, in Pittsburgh’s Steel Valley; education: earned a scholarship to Harvard University, graduated with honors, 1967; law degree, Dickinson School of Law; military service: U.S. Army; served as an infantry staff sergeant in Vietnam; awarded the Bronze Star for Valor; profession: Attorney; public service: Assistant District Attorney, Erie County, PA; U.S. House of Representatives, 1983–1995; Governor of Pennsylvania, 1995–2001; family: married to Michele; children: Lesley and Tommy; appointed by President George W. Bush as Office of Homeland Security Advisor, October 8, 2001; nominated by President Bush to become the 1st Secretary of Homeland Security on November 25, 2002, and was confirmed by the U.S. Senate on January 22, 2003. OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY Secretary of Homeland Security.—Tom Ridge. OFFICE OF THE DEPUTY SECRETARY Deputy Secretary of Homeland Security.—James Loy. OFFICE OF THE CHIEF OF STAFF Chief of Staff.—Duncan Campbell. MANAGEMENT DIRECTORATE Under Secretary.—Janet Hale. Chief Financial Officer.—Bruce Carnes. Chief Information Officer.—Steven Cooper. Chief Human Capital Officer.—Ronald James. BORDER AND TRANSPORTATION SECURITY DIRECTORATE Under Secretary.—Asa Hutchinson. Assistant Secretary for the Bureau of Immigration and Customs Enforcement.—Michael J. Garcia. Assistant Secretary for Policy and Planning.—Stewart Verdery. Commissioner, Customs and Border Protection.—Robert Bonner. Administrator, Transportation Security Administration.—David Stone (acting). SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY DIRECTORATE Under Secretary.—Charles E. McQueary. 759 760 Congressional Directory INFORMATION ANALYSIS AND INFRASTRUCTURE PROTECTION DIRECTORATE Under Secretary.—Frank Libutti. -

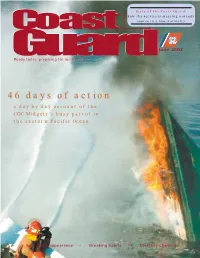

46 Days of Action 46 Days of Action

State of the Coast Guard: how the service is steering a steady CCoastoast course to a new normalcy GuaGuarrdd June 2002 Ready today, preparing for tomorrow 4646 daysdays ofof actionaction a day by day account of the CGC Midgett’s busy patrol in the eastern Pacific Ocean Late Show appearance - Breaking habits - Diversity challenge Heroes The world’s best Coast Guard , DINFOS ALL H EFF A1 J P Lt. Troy Beshears Lt. Cmdr. Brian Moore AST1 John Green AMT1 Michael Bouchard Coast Guard Air Station New Orleans Lt. Cmdr. Moore, Lt. Beshears, AST1 Green and As the helicopter crew returned to the rig and AMT1 Bouchard received a Distinguished Flying prepared to pick up Green, who stayed on the rig to Cross Jan. 20, 2001, for their actions during a rescue coordinate the entire evacuation, the rig exploded into July 5, 2000. a ball of fire that extended from the water The four-man crew was honored for line to 100 feet above the platform. rescuing 51 people from a burning oil rig in the Unsure whether Green was still alive, the crew then Gulf of Mexico. navigated the helicopter into the thick, black column The crew responded to the fire and safely airlifted of smoke to retrieve Green, who was uninjured. 15 people to a nearby platform nine miles from the The Distinguished Flying Cross is the highest fire. The crew evacuated another 36 people to heroism award involving flight that the Coast Guard awaiting boats. can award during peacetime. Coast Guard June 2002 U.S. Department of Transportation Features Guiding Principle: Stand the Watch 8 Diary of action By Lt. -

Nomination of Admiral James M. Loy Hearing Committee On

S. Hrg. 108–332 NOMINATION OF ADMIRAL JAMES M. LOY HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENTAL AFFAIRS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED EIGHTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION ON THE NOMINATION OF ADMIRAL JAMES M. LOY TO BE DEPUTY SECRETARY OF HOMELAND SECURITY NOVEMBER 18, 2003 Printed for the use of the Committee on Governmental Affairs ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 91–044 PDF WASHINGTON : 2004 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 0ct 09 2002 10:20 Apr 05, 2004 Jkt 091044 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 C:\DOCS\91044.TXT SAFFAIRS PsN: PHOGAN COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENTAL AFFAIRS SUSAN M. COLLINS, Maine, Chairman TED STEVENS, Alaska JOSEPH I. LIEBERMAN, Connecticut GEORGE V. VOINOVICH, Ohio CARL LEVIN, Michigan NORM COLEMAN, Minnesota DANIEL K. AKAKA, Hawaii ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania RICHARD J. DURBIN, Illinois ROBERT F. BENNETT, Utah THOMAS R. CARPER, Deleware PETER G. FITZGERALD, Illinois MARK DAYTON, Minnesota JOHN E. SUNUNU, New Hampshire FRANK LAUTENBERG, New Jersey RICHARD C. SHELBY, Alabama MARK PRYOR, Arkansas MICHAEL D. BOPP, Staff Director and Chief Counsel JOHANNA L. HARDY, Senior Counsel TIM RADUCHA-GRACE, Professional Staff Member JOYCE A. RECHTSCHAFFEN, Minority Staff Director and Counsel HOLLY A. IDELSON, Minority Counsel JENNIFER E. HAMILTON, Minority Research Assistant AMY B. NEWHOUSE, Chief Clerk (II) VerDate 0ct 09 2002 10:20 Apr 05, 2004 Jkt 091044 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 C:\DOCS\91044.TXT SAFFAIRS PsN: PHOGAN C O N T E N T S Opening statements: Page Senator Collins ................................................................................................ -

Developing Character Adn Aligning Peersonal Values with Organizational Values in the US Coast Guard

DEVELOPING CHARACTER AND ALIGNING PERSONAL VALUES WITH ORGANIZATIONAL VALUES IN THE UNITED STATES COAST GUARD A thesis presented to the Faculty of the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF MILITARY ART AND SCIENCE General Studies by LUANN BARNDT, LCDR, USCG B.S., United States Coast Guard Academy, New London, Connecticut, 1984 M.S., The George Washington University, Washington, DC, 1993 Fort Leavenworth, Kansas 2000 Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. MASTER OF MILITARY ART AND SCIENCE THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Name of Candidate: LCDR Luann Barndt Thesis Title: Developing Character and Aligning Values in the U.S. Coast Guard Approved by: , Thesis Committee Chairman Ronald E. Cuny, Ed.D. , Member CDR Robert M. Brown, M.S. , Member LTC Jeffrey L. Irvine, B.A. Approved this 2d day of June 2000 by: , Director, Graduate Degree Programs Philip J. Brookes, Ph.D. The opinions and conclusions expressed herein are those of the student author and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College or any other governmental agency. (References to this study should include the foregoing statement.) ii ABSTRACT DEVELOPING CHARACTER AND ALIGNING PERSONAL VALUES WITH ORGANIZATIONAL VALUES IN THE UNITED STATES COAST GUARD BY LCDR Luann Barndt, USCG, 151 pages. This study investigates the best method for developing character and aligning personal and organizational values in the United States Coast Guard. All five of the military services embarked on comprehensive efforts to develop character and teach core values. Several environmental and cultural events inspired this endeavor. -

Senate Hearings Before the Committee on Appropriations

S. HRG. 109–195 Senate Hearings Before the Committee on Appropriations Department of Homeland Security Fiscal Year 2006 109th CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION H.R. 2360 DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY NONDEPARTMENTAL WITNESSES Department of Homeland Security, 2006 (H.R. 2360) S. HRG. 109–195 DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY APPROPRIATIONS FOR FISCAL YEAR 2006 HEARINGS BEFORE A SUBCOMMITTEE OF THE COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED NINTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION ON H.R. 2360 AN ACT MAKING APPROPRIATIONS FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF HOME- LAND SECURITY FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDING SEPTEMBER 30, 2006, AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES Department of Homeland Security Nondepartmental witnesses Printed for the use of the Committee on Appropriations ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.gpoaccess.gov/congress/index.html U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 99–863 PDF WASHINGTON : 2005 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi, Chairman TED STEVENS, Alaska ROBERT C. BYRD, West Virginia ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania DANIEL K. INOUYE, Hawaii PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico PATRICK J. LEAHY, Vermont CHRISTOPHER S. BOND, Missouri TOM HARKIN, Iowa MITCH MCCONNELL, Kentucky BARBARA A. MIKULSKI, Maryland CONRAD BURNS, Montana HARRY REID, Nevada RICHARD C. SHELBY, Alabama HERB KOHL, Wisconsin JUDD GREGG, New Hampshire PATTY MURRAY, Washington ROBERT F. BENNETT, Utah BYRON L. DORGAN, North Dakota LARRY CRAIG, Idaho DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas RICHARD J. DURBIN, Illinois MIKE DEWINE, Ohio TIM JOHNSON, South Dakota SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas MARY L. -

Department of Homeland Security U.S

DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY U.S. Naval Security Station, 3801 Nebraska Avenue, NW., Washington, DC 20393 phone 282–8000 TOM RIDGE, Secretary of Homeland Security; born on August 26, 1945, in Pittsburgh’s Steel Valley; education: earned a scholarship to Harvard University, graduated with honors, 1967; law degree, Dickinson School of Law; military service: U.S. Army; served as an infantry staff sergeant in Vietnam; awarded the Bronze Star for Valor; profession: Attorney; public service: Assistant District Attorney, Erie County, PA; U.S. House of Representatives, 1983–1995; Governor of Pennsylvania, 1995–2001; family: married to Michele; children: Lesley and Tommy; appointed by President George W. Bush as Office of Homeland Security Advisor, October 8, 2001; nominated by President Bush to become the 1st Secretary of Homeland Security on November 25, 2002, and was confirmed by the U.S. Senate on January 22, 2003. OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY Secretary of Homeland Security.—Tom Ridge. OFFICE OF THE DEPUTY SECRETARY Deputy Secretary of Homeland Security.—[Vacant]. OFFICE OF THE CHIEF OF STAFF Chief of Staff.—Duncan Campbell. MANAGEMENT DIRECTORATE Under Secretary.—Janet Hale. Chief Financial Officer.—Bruce Carnes. Chief Information Officer.—Steven Cooper. Chief Human Capital Officer.—Ronald James. BORDER AND TRANSPORTATION SECURITY DIRECTORATE Under Secretary.—Asa Hutchinson. Assistant Secretary for Policy and Planning.—Stewart Verdery. Commissioner, Customs and Border Protection.—Robert Bonner. Administrator, Transportation Security Administration.—James Loy. SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY DIRECTORATE Under Secretary.—Charles E. McQueary. 759 760 Congressional Directory INFORMATION ANALYSIS AND INFRASTRUCTURE PROTECTION DIRECTORATE Under Secretary.—Frank Libutti. Assistant Secretary for Infrastructure Protection.—Robert Liscouski. EMERGENCY PREPAREDNESS AND RESPONSE DIRECTORATE Under Secretary.—Michael Brown. -

STEPHEN E. FLYNN, Ph.D. Founding Director, Global Resilience Institute Professor of Political Science Northeastern University, Boston, MA [email protected]

STEPHEN E. FLYNN, Ph.D. Founding Director, Global Resilience Institute Professor of Political Science Northeastern University, Boston, MA [email protected] EDUCATION: • Ph.D. in International Relations, The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, Tufts University, 1991 • M.A.L.D. in International Relations, The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, Tufts University, 1990 • B.S. in Government, U.S. Coast Guard Academy, 1982 ACADEMIC AWARDS: • Honorary Doctorate of Laws, Monmouth University, 2009 • Pew Faculty Fellowship in International Affairs, John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, 1994-95 • Annenberg Scholar-in-Resident, Annenberg School for Communication, University of Pennsylvania, 1993-94 • Council on Foreign Relations’ International Affairs Fellowship, Foreign Policy Studies Program, The Brookings Institution, 1991-92 • Edmund A Gullion Prize, Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, Tufts University, 1988, for highest academic achievement • Veterans of Foreign Wars Prize, U.S. Coast Guard Academy, 1982, for highest academic achievement in the Humanities • The Daughters of American Revolution Prize, U.S. Coast Guard Academy, 1982, for highest academic achievement in American History PROFESSIONAL AWARDS: • The Infrastructure Security Partnership Annual Award for Distinguished Leadership in Critical Infrastructure Resilience, 2010 • Top 25 Most Influential People in Security 2009, Security Magazine • Maritime Security Service Recognition Award, 2005, presented by the Maritime Security Council for outstanding leadership in raising the standards of maritime security worldwide • Alumni Achievement Award, U.S. Coast Guard Academy Alumni Association, 1999, for recognition of the graduate within the past 20 years who has an outstanding record of achievement and promise of lifelong distinction. • Legion of Merit Medal, 2001 • Meritorious Service Medal, 1992 • U.S. -

Spring 2005 Edition

SPRING 2005 PROVIDING CUTTING-EDGE KNOWLEDGE TO The Business GOVERNMENT LEADERS of Government 3 From the Editor’s Keyboard 4 Conversations with Leaders A Conversation with Kenneth Feinberg A Conversation with Admiral James Loy 15 Profiles in Leadership Ambassador Prudence Bushnell Ambassador Prudence Bushnell Patrick R. Donahoe William E. Gray Patrick R. Donahoe William E. Gray Ira L. Hobbs Fran P. Mainella Michael Montelongo Kimberly T. Nelson Rebecca Spitzgo Major General Charles E. Williams 42 Forum: The Second Term Forum Introduction: The Second Term of George W. Bush Ira L. Hobbs Fran P. Mainella Michael Montelongo 44 The Second Term: Insights for Political Appointees The Biggest Secret in Washington Getting to Know You Performance Management for Political Executives 54 The Second Term: Major Challenges Looking Ahead: Drivers for Change President’s Management Agenda: What Comes Next? Kimberly T. Nelson Rebecca Spitzgo Major General Charles E. Williams Challenge 1: Public-Private Competition Challenge 2: Pay for Performance Challenge 3: Government Reorganization Challenge 4: Managing for Results 85 Research Abstracts www.businessofgovernment.org Discover the best ideas in government REPORTS HOW TO ORDER 2004 Presidential Transition Series Human Capital Management Series Reports Getting to Know You: Rules of Engagement Pay for Performance: A Guide for Federal Download from: for Political Appointees and Career Executives Managers by Howard Risher www.businessofgovernment.org. by Joseph A. Ferrara and Lynn C. Ross Managing for Performance and Results Series To order a hard copy, go to: Becoming an Effective Political Executive: Staying the Course: The Use of Performance www.businessofgovernment.org/order. 7 Lessons from Experienced Appointees Measurement in State Governments (2nd edition) by Judith E. -

Hurricane Katrina: a Nation Still Unprepared

109th Congress SPECIAL REPORT S. Rept. 109-322 2nd Session HURRICANE KATRINA: A NATION STILL UNPREPARED SPECIAL REPORT OF THE COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY AND GOVERNMENTAL AFFAIRS UNITED STATES SENATE TOGETHER WITH ADDITIONAL VIEWS Printed for the Use of the Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Aff airs http://hsgac.senate.gov/ ORDERED TO BE PRINTED U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 2006 FOR SALE BY THE SUPERINTENDENT OF DOCUMENTS Cover Photo: Helicopter Rescue, New Orleans (Courtesy of U.S. Coast Guard) For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512-1800; DC area (202) 512-1800 Fax: (202) 512-2250 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402-0001 ISBN 0-16-076749-0 Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Aff airs SUSAN M. COLLINS, Maine, Chairman TED STEVENS, Alaska JOSEPH I. LIEBERMAN, Connecticut GEORGE V. VOINOVICH, Ohio CARL LEVIN, Michigan NORM COLEMAN, Minnesota DANIEL K. AKAKA, Hawaii TOM COBURN, M.D., Oklahoma THOMAS R. CARPER, Delaware LINCOLN D. CHAFEE, Rhode Island MARK DAYTON, Minnesota ROBERT F. BENNETT, Utah FRANK LAUTENBERG, New Jersey PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico MARK PRYOR, Arkansas JOHN W. WARNER, Virginia Michael D. Bopp, Majority Staff Director and Chief Counsel David T. Flanagan, Majority General Counsel, Katrina Investigation Joyce A. Rechtschaff en, Minority Staff Director and Counsel Laurie R. Rubenstein, Minority Chief Counsel Robert F. Muse, Minority General Counsel, Katrina Investigation Trina Driessnack Tyrer, Chief Clerk Majority Staff Minority Staff Arthur W Adelberg, Senior Counsel Michael L. Alexander, Professional Staff Member* Melvin D. Albritton, Counsel Alistair F. -

Department of Homeland Security U.S

DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY U.S. Naval Security Station, 3801 Nebraska Avenue, NW., Washington, DC 20393 phone 282–8000 TOM RIDGE, Secretary of Homeland Security; born on August 26, 1945, in Pittsburgh’s Steel Valley; education: earned a scholarship to Harvard University, graduated with honors, 1967; law degree, Dickinson School of Law; military service: U.S. Army; served as an infantry staff sergeant in Vietnam; awarded the Bronze Star for Valor; profession: Attorney; public service: Assistant District Attorney, Erie County, PA; U.S. House of Representatives, 1983–1995; Governor of Pennsylvania, 1995–2001; family: married to Michele; children: Lesley and Tommy; appointed by President George W. Bush as Office of Homeland Security Advisor, October 8, 2001; nominated by President Bush to become the 1st Secretary of Homeland Security on November 25, 2002, and was confirmed by the U.S. Senate on January 22, 2003. OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY Secretary of Homeland Security.—Tom Ridge. OFFICE OF THE DEPUTY SECRETARY Deputy Secretary of Homeland Security.—James Loy. OFFICE OF THE CHIEF OF STAFF Chief of Staff.—Duncan Campbell. MANAGEMENT DIRECTORATE Under Secretary.—Janet Hale. Chief Financial Officer.—Bruce Carnes. Chief Information Officer.—Steven Cooper. Chief Human Capital Officer.—Ronald James. BORDER AND TRANSPORTATION SECURITY DIRECTORATE Under Secretary.—Asa Hutchinson. Assistant Secretary for the Bureau of Immigration and Customs Enforcement.—Michael J. Garcia. Assistant Secretary for Policy and Planning.—Stewart Verdery. Commissioner, Customs and Border Protection.—Robert Bonner. Administrator, Transportation Security Administration.—David Stone (acting). SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY DIRECTORATE Under Secretary.—Charles E. McQueary. 759 760 Congressional Directory INFORMATION ANALYSIS AND INFRASTRUCTURE PROTECTION DIRECTORATE Under Secretary.—Frank Libutti. -

Extensions of Remarks E899 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS

May 24, 2002 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks E899 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS JEWELENE SPENCER: A DIAMOND IN HONOR OF COLORADO ADM. JAMES M. LOY’S IN THE CLASSROOM PRESERVATION, INC. RETIREMENT HON. FRANK A. LOBIONDO HON. JAMES A. BARCIA HON. MARK UDALL OF NEW JERSEY OF MICHIGAN OF COLORADO IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Wednesday, May 22, 2002 IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Mr. LOBIONDO. Mr. Speaker, I rise today to Wednesday, May 22, 2002 Wednesday, May 22, 2002 honor a very special patriot who has com- mitted his entire career to the mission of de- Mr. BARCIA. Mr. Speaker, I rise today to Mr. UDALL of Colorado. Mr. Speaker, I rise fending America. Admiral James M. Loy, com- honor my good friend, Jewelene M. Spencer, today to recognize the important and con- mandant of the United States Coast Guard, is as she prepares to retire after 40 years as an tinuing contributions that Colorado Preserva- retiring from duty at the end of May and will educator, the past 32 of which were spent with tion, Inc. has made to historic and archeo- bring to a close his remarkable 38-year ca- Oscoda Area Schools. Jewel’s dedication and logical preservation in Colorado. reer. demand for excellence has made her an in- Too often our communities can lose their Admiral Loy, a 1964 graduate of the Coast valuable part of the school system and the en- history in pieces, not realizing until it is gone Guard Academy, spent much of his career on tire community for many years. -

Testimony of Patricia Mcginnis, President and CEO Council For

Board of Trustees Testimony of HONORARY CO-CHAIRS Patricia McGinnis, President and CEO President George H.W. Bush President Jimmy Carter Council for Excellence in Government President William Jefferson Clinton Before the Subcommittee on Oversight of Government Management, CHAIR the Federal Workforce and the District of Columbia John D. Macomber U.S. Senate VICE CHAIRS Patrick W. Gross Maxine Isaacs September 18, 2008 TREASURER Joseph E. Kasputys Thank you Mr. Chairman, Senator Voinovich and members of the SECRETARY subcommittee, for inviting me to participate in this important discussion J.T. Smith II about keeping the nation safe through the presidential transition. As we have TRUSTEES Jodie T. Allen seen in Spain and the U.K., national elections and transitions present Dennis W. Bakke opportunities for terrorists to exploit potential gaps in leadership continuity. Colin C. Blaydon Richard E. Cavanagh A devastating natural disaster could also test the continuity of our nation’s William F. Clinger Jr. Abby Joseph Cohen emergency response enterprise during this period. Robert H. Craft Jr. Thomas Dohrmann William H. Donaldson As you know, the Council for Excellence in Government is a non-profit, Cal Dooley Leslie C. Francis non-partisan organization that works to improve the performance of William Galston government and accountability to its owners and customers, the American Dan Glickman Lee H. Hamilton people. Edwin L. Harper James F. HInchman Arthur H. House The Council has played a significant role in presidential transitions. Both the Suzanne Nora Johnson Gwendolyn S. King Clinton and Bush Administrations called upon the Council to help organize Susan R.