Senate Hearings Before the Committee on Appropriations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Senate Republican Conference John Thune

HISTORY, RULES & PRECEDENTS of the SENATE REPUBLICAN CONFERENCE JOHN THUNE 115th Congress Revised January 2017 HISTORY, RULES & PRECEDENTS of the SENATE REPUBLICAN CONFERENCE Table of Contents Preface ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... 1 Rules of the Senate Republican Conference ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....2 A Service as Chairman or Ranking Minority Member ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... 4 B Standing Committee Chair/Ranking Member Term Limits ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... 4 C Limitations on Number of Chairmanships/ Ranking Memberships ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... 4 D Indictment or Conviction of Committee Chair/Ranking Member ....... ....... ....... .......5 ....... E Seniority ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... 5....... ....... ....... ...... F Bumping Rights ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... 5 G Limitation on Committee Service ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ...5 H Assignments of Newly Elected Senators ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... 5 Supplement to the Republican Conference Rules ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... 6 Waiver of seniority rights ..... -

Committee on Appropriations UNITED STATES SENATE 135Th Anniversary

107th Congress, 2d Session Document No. 13 Committee on Appropriations UNITED STATES SENATE 135th Anniversary 1867–2002 U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 2002 ‘‘The legislative control of the purse is the central pil- lar—the central pillar—upon which the constitutional temple of checks and balances and separation of powers rests, and if that pillar is shaken, the temple will fall. It is...central to the fundamental liberty of the Amer- ican people.’’ Senator Robert C. Byrd, Chairman Senate Appropriations Committee United States Senate Committee on Appropriations ONE HUNDRED SEVENTH CONGRESS ROBERT C. BYRD, West Virginia, TED STEVENS, Alaska, Ranking Chairman THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi ANIEL NOUYE Hawaii D K. I , ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania RNEST OLLINGS South Carolina E F. H , PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico ATRICK EAHY Vermont P J. L , CHRISTOPHER S. BOND, Missouri OM ARKIN Iowa T H , MITCH MCCONNELL, Kentucky ARBARA IKULSKI Maryland B A. M , CONRAD BURNS, Montana ARRY EID Nevada H R , RICHARD C. SHELBY, Alabama ERB OHL Wisconsin H K , JUDD GREGG, New Hampshire ATTY URRAY Washington P M , ROBERT F. BENNETT, Utah YRON ORGAN North Dakota B L. D , BEN NIGHTHORSE CAMPBELL, Colorado IANNE EINSTEIN California D F , LARRY CRAIG, Idaho ICHARD URBIN Illinois R J. D , KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas IM OHNSON South Dakota T J , MIKE DEWINE, Ohio MARY L. LANDRIEU, Louisiana JACK REED, Rhode Island TERRENCE E. SAUVAIN, Staff Director CHARLES KIEFFER, Deputy Staff Director STEVEN J. CORTESE, Minority Staff Director V Subcommittee Membership, One Hundred Seventh Congress Senator Byrd, as chairman of the Committee, and Senator Stevens, as ranking minority member of the Committee, are ex officio members of all subcommit- tees of which they are not regular members. -

110Th Congress 145

MISSISSIPPI 110th Congress 145 MISSISSIPPI (Population 2000, 2,844,658) SENATORS THAD COCHRAN, Republican, of Jackson, MS; born in Pontotoc, MS, December 7, 1937; education: B.A., University of Mississippi, 1959; J.D., University of Mississippi Law School, 1965; received a Rotary Foundation Fellowship and studied international law and jurisprudence at Trinity College, University of Dublin, Ireland, 1963–64; military service: served in U.S. Navy, 1959–61; professional: admitted to Mississippi bar in 1965; board of directors, Jackson Rotary Club, 1970–71; Outstanding Young Man of the Year Award, Junior Chamber of Com- merce in Mississippi, 1971; president, young lawyers section of Mississippi State bar, 1972–73; married: the former Rose Clayton of New Albany, MS, 1964; two children and three grandchildren; committees: Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry; Appropriations; Rules and Ad- ministration; elected to the 93rd Congress, November 7, 1972; reelected to 94th and 95th Con- gresses; chairman of the Senate Republican Conference, 1990–96; elected to the U.S. Senate, November 7, 1978, for the six-year term beginning January 3, 1979; subsequently appointed by the governor, December 27, 1978, to fill the vacancy caused by the resignation of Senator James O. Eastland; reelected to each succeeding Senate term. Office Listings http://cochran.senate.gov 113 Dirksen Senate Office Building, Washington, DC 20510 .................................... (202) 224–5054 Chief of Staff.—Jenny Manley. Legislative Director.—T.A. Hawks. Press Secretary.—Margaret Wicker. Scheduler.—Doris Wagley. 188 East Capitol Street, Suite 614, Jackson, MS 39201 ............................................. (601) 965–4459 P.O. Box 1434, Oxford, MS 38655 .............................................................................. (662) 236–1018 14094 Customs Boulevard, Suite 201, Gulfport, MS 39503 ...................................... -

The Trent Lott Leadership Institute Newsletter

The Trent Lott Leadership Institute NewSletter IN THIS ISSUE: LOTT ABROAD . .2 ALUMNI SPOTLIGHT . 3 DR. CHEN IS BACK! . .5 DEBATE TEAM RECAP . .. 5 INTERNSHIP OPPORTUNITIES . 6 SAVE THE DATES . .. .7 NEWS AND EVENTS . .. .8 LOTT ABROAD This past semester and over winter break, two Lott students represented PPL in various parts of the world. Mason Myers, (‘20) and Ella Endorf (‘22) studied abroad and are sharing their experiences with the newsletter. We are so proud of their accomplishments and know that they will continue to represent the Lott Institute in their future endeavors! “Studying abroad for a semester in Melbourne, Australia was one of the most rewarding things I’ve done at Ole Miss. I was nervous about being so far from home but I grew as a person and was able to experience so much. I joined a sports club, traveled all over Australia and New Zealand, and made life long friends. I took some of the most interesting classes involving Australian foreign policy and Australian culture. Overall, my experience abroad challenged me and broadened my perspective of the world.” -- Mason Myers (‘20) “I spent a month in Salerno learning all about the rich culture and history of southern Italy. I took Italian classes and conversed exclusively in Italian with my host family. I walked on the lungomare, or seafront, on the way to class each morning and spent my afternoons at the beach or shopping. On the weekends, I traveled around the Campania region, visiting Naples, Pompeii, and Caserta -- known as the “Italian Versailles.” When I wasn’t studying or traveling, I explored Salerno. -

Senate Hearings Before the Committee on Appropriations

S. HRG. 111–859 Senate Hearings Before the Committee on Appropriations Department of the Interior, Environment, and Related Agencies Appropriations Fiscal Year 2011 111th CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY NONDEPARTMENTAL WITNESSES Department of the Interior, Environment, and Related Agencies Appropriations, 2011 S. HRG. 111–859 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR, ENVIRONMENT, AND RELATED AGENCIES APPROPRIATIONS FOR FISCAL YEAR 2011 HEARINGS BEFORE A SUBCOMMITTEE OF THE COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED ELEVENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION Department of Agriculture Department of the Interior Environmental Protection Agency Nondepartmental Witnesses Printed for the use of the Committee on Appropriations ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 54–974 PDF WASHINGTON : 2011 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS DANIEL K. INOUYE, Hawaii, Chairman ROBERT C. BYRD, West Virginia THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi PATRICK J. LEAHY, Vermont CHRISTOPHER S. BOND, Missouri TOM HARKIN, Iowa MITCH MCCONNELL, Kentucky BARBARA A. MIKULSKI, Maryland RICHARD C. SHELBY, Alabama HERB KOHL, Wisconsin JUDD GREGG, New Hampshire PATTY MURRAY, Washington ROBERT F. BENNETT, Utah BYRON L. DORGAN, North Dakota KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas RICHARD J. DURBIN, Illinois LAMAR ALEXANDER, Tennessee TIM JOHNSON, South Dakota SUSAN COLLINS, Maine MARY L. LANDRIEU, Louisiana GEORGE V. VOINOVICH, Ohio JACK REED, Rhode Island LISA MURKOWSKI, Alaska FRANK R. -

The State of the Presidential Appointment Process

S. Hrg. 107–118 THE STATE OF THE PRESIDENTIAL APPOINTMENT PROCESS HEARINGS BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENTAL AFFAIRS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED SEVENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION APRIL 4 AND 5, 2001 Printed for the use of the Committee on Governmental Affairs ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 72–498 PDF WASHINGTON : 2002 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 08:53 Mar 13, 2002 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 72498.TXT SAFFAIRS PsN: SAFFAIRS COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENTAL AFFAIRS FRED THOMPSON, Tennessee, Chairman TED STEVENS, Alaska JOSEPH I. LIEBERMAN, Connecticut SUSAN M. COLLINS, Maine CARL LEVIN, Michigan GEORGE V. VOINOVICH, Ohio DANIEL K. AKAKA, Hawaii PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico RICHARD J. DURBIN, Illinois THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi ROBERT G. TORRICELLI, New Jersey JUDD GREGG, New Hampshire MAX CLELAND, Georgia ROBERT F. BENNETT, Utah THOMAS R. CARPER, Delaware JEAN CARNAHAN, Missouri HANNAH S. SISTARE, Staff Director and Counsel DAN G. BLAIR, Senior Counsel ROBERT J. SHEA, Counsel JOHANNA L. HARDY, Counsel JOYCE A. RECHTSCHAFFEN, Democratic Staff Director and Counsel SUSAN E. PROPPER, Democratic Counsel DARLA D. CASSELL, Chief Clerk (II) VerDate 11-MAY-2000 08:53 Mar 13, 2002 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 72498.TXT SAFFAIRS PsN: SAFFAIRS C O N T E N T S Page Opening statements: Senator Thompson ............................................................................................ 1, 49 Senator Akaka .................................................................................................. 2 Senator Voinovich ............................................................................................ -

MISSISSIPPI LEGISLATURE REGULAR SESSION 2018 By: Senator(S) Burton, Barnett, Blackmon, Blackwell, Blount, Branning, Brown

MISSISSIPPI LEGISLATURE REGULAR SESSION 2018 By: Senator(s) Burton, Barnett, To: Rules Blackmon, Blackwell, Blount, Branning, Browning, Bryan, Butler, Carmichael, Carter, Caughman, Chassaniol, Clarke, Dawkins, DeBar, Dearing, Doty, Fillingane, Frazier, Gollott, Harkins, Hill, Hopson, Horhn, Hudson, Jackson (11th), Jackson (15th), Jackson (32nd), Jolly, Jordan, Kirby, Massey, McDaniel, McMahan, Michel, Moran, Norwood, Parker, Parks, Polk, Seymour, Simmons (12th), Simmons (13th), Tollison, Turner-Ford, Watson, Whaley, Wiggins, Wilemon, Witherspoon, Younger SENATE CONCURRENT RESOLUTION NO. 641 1 A CONCURRENT RESOLUTION RECOGNIZING THE LASTING LEGACY OF 2 RETIRING UNITED STATES SENATOR THAD COCHRAN. 3 WHEREAS, April 1, 2018, will truly be the end of an era in 4 Mississippi politics. That is the day longtime United States 5 Senator and Northeast Mississippi native Thad Cochran will step 6 down from his seat after 46 years representing the Magnolia State 7 in Washington, D.C. Senator Cochran was Chairman of the Senate 8 Appropriations Committee; and 9 WHEREAS, Mississippians owe Senator Cochran a debt of 10 gratitude for his service over the last several decades. For 11 always seeking to make Mississippi a better place for all its 12 residents, we thank Senator Cochran and wish him a long and 13 well-deserved retirement; and 14 WHEREAS, Senator Cochran was first elected to the Senate in 15 1978, becoming the first Republican in more than 100 years to win 16 a statewide election in Mississippi. He is the 10th S. C. R. No. 641 *SS02/R1296* ~ OFFICIAL ~ N1/2 18/SS02/R1296 PAGE 1 (tb\ar) 17 longest-serving Senator in U.S. history. Senator Cochran was 18 reelected in 2014 to a seventh six-year term that began in January 19 2015 as Chairman of the powerful Senate Appropriations Committee, 20 a post he had held briefly in the mid-2000s and was scheduled to 21 continue through 2018. -

Department of Homeland Security U.S

DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY U.S. Naval Security Station, 3801 Nebraska Avenue, NW., Washington, DC 20393 phone 282–8000 TOM RIDGE, Secretary of Homeland Security; born on August 26, 1945, in Pittsburgh’s Steel Valley; education: earned a scholarship to Harvard University, graduated with honors, 1967; law degree, Dickinson School of Law; military service: U.S. Army; served as an infantry staff sergeant in Vietnam; awarded the Bronze Star for Valor; profession: Attorney; public service: Assistant District Attorney, Erie County, PA; U.S. House of Representatives, 1983–1995; Governor of Pennsylvania, 1995–2001; family: married to Michele; children: Lesley and Tommy; appointed by President George W. Bush as Office of Homeland Security Advisor, October 8, 2001; nominated by President Bush to become the 1st Secretary of Homeland Security on November 25, 2002, and was confirmed by the U.S. Senate on January 22, 2003. OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY Secretary of Homeland Security.—Tom Ridge. OFFICE OF THE DEPUTY SECRETARY Deputy Secretary of Homeland Security.—James Loy. OFFICE OF THE CHIEF OF STAFF Chief of Staff.—Duncan Campbell. MANAGEMENT DIRECTORATE Under Secretary.—Janet Hale. Chief Financial Officer.—Bruce Carnes. Chief Information Officer.—Steven Cooper. Chief Human Capital Officer.—Ronald James. BORDER AND TRANSPORTATION SECURITY DIRECTORATE Under Secretary.—Asa Hutchinson. Assistant Secretary for the Bureau of Immigration and Customs Enforcement.—Michael J. Garcia. Assistant Secretary for Policy and Planning.—Stewart Verdery. Commissioner, Customs and Border Protection.—Robert Bonner. Administrator, Transportation Security Administration.—David Stone (acting). SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY DIRECTORATE Under Secretary.—Charles E. McQueary. 759 760 Congressional Directory INFORMATION ANALYSIS AND INFRASTRUCTURE PROTECTION DIRECTORATE Under Secretary.—Frank Libutti. -

Liversity's Graduate Department Is Model of Educational Methods

Marching Song to Glee Club Sings in Be Presented Intercollegiate*. Saturday. THE March 10th. 9. New York, N. Y.( March 9, 1928 No. 21 liversity's Graduate Department Harvester Club Sponsors Amateur Is Model of Educational Methods Boxing Tournament in Gymnasium Concentration Areas Accepted Version of 'TAe Sp*alwr* CAeoM Topic* for Proceeds to Buy Motor for f Prepare Way for Finer Ram" Variet From Original Annual Oratorical Contut Rev. James Hayes—Event Dissertation Work. In preparing his orchestration of "The Pordham Ram Seng," which Each contestant in the Annual Slated for March 29. will be playtd along with some Oratorical Contest has already se- N. V. U. songs at the bouts this lected ths subject for his speech. SEARCH STRESSED coming Saturday, Howard Lilly The chosen topics and their au- F. LAWLESS CHAIRMAN eonsultsd ths original copy of the thors follow: song preserved In the Fordham Li- "Is America Selfish?" by James - Tests for Ph. D. and brary archives. It wss discovered, H. Burns, '2S; "Lincoln" by James Fr. Deane Permits Use of Gym that the aoceptsd way of singing K. Seery, VS; "Governor Smith" by (Department Heads Feature "Ths Ram" was different from the Harold J. McAulay, '21; "Ths Con- and A. A. Moderator Aids Perfected System. original. The trio usually sung— stitution" by James J. McCarthy, "With a Ram, etc."—should read: Jr., '21; "Hamilton" by. Edward J. Committee. i Lst us cheer with s Ram, a Ram, MeNally, '2»i "Ireland's Indepen- a Ram for loyalty; and again with dence" by James •>. Cssey, 'SO; The Graduate Department of Ford-1 The Harvester Club is sponsoring am University, situated In the Wool- a Ram, a Ram, a Ram for victory; "Woodrow Wilson" by Francis A. -

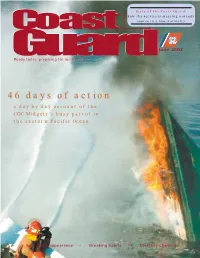

46 Days of Action 46 Days of Action

State of the Coast Guard: how the service is steering a steady CCoastoast course to a new normalcy GuaGuarrdd June 2002 Ready today, preparing for tomorrow 4646 daysdays ofof actionaction a day by day account of the CGC Midgett’s busy patrol in the eastern Pacific Ocean Late Show appearance - Breaking habits - Diversity challenge Heroes The world’s best Coast Guard , DINFOS ALL H EFF A1 J P Lt. Troy Beshears Lt. Cmdr. Brian Moore AST1 John Green AMT1 Michael Bouchard Coast Guard Air Station New Orleans Lt. Cmdr. Moore, Lt. Beshears, AST1 Green and As the helicopter crew returned to the rig and AMT1 Bouchard received a Distinguished Flying prepared to pick up Green, who stayed on the rig to Cross Jan. 20, 2001, for their actions during a rescue coordinate the entire evacuation, the rig exploded into July 5, 2000. a ball of fire that extended from the water The four-man crew was honored for line to 100 feet above the platform. rescuing 51 people from a burning oil rig in the Unsure whether Green was still alive, the crew then Gulf of Mexico. navigated the helicopter into the thick, black column The crew responded to the fire and safely airlifted of smoke to retrieve Green, who was uninjured. 15 people to a nearby platform nine miles from the The Distinguished Flying Cross is the highest fire. The crew evacuated another 36 people to heroism award involving flight that the Coast Guard awaiting boats. can award during peacetime. Coast Guard June 2002 U.S. Department of Transportation Features Guiding Principle: Stand the Watch 8 Diary of action By Lt. -

Mrs. James Roosevelt Here Sunday

Students to Sing and Swing to "Fordham Forever" . Story on Page 3 Smith Scouts Tilden Downs Cafeteria Richards Page 7 Page 6 Vol. 20 New York, N. Y., September 29, 1939 No. 2 MRS. JAMES ROOSEVELT HERE SUNDAY President's Mother to Pre- side at Plaque Ceremony MASS OF HOLY GHOST WEDNESDAY On Campus By FRANK FORD Traditional Mass to Formally Open Uptown College; Eight Mother of a President Rose Hill will see one of the na- Thousand Students Return to University tion's most respected mothers and one of America's honor citizens when With the school's centenary just one year in the offing, Fordham Uni- Mrs. James Roosevelt, mother of versity this week swung into its ninety-ninth year as more than eight the President of the United States, thousand students moved onto two campuses and began the business of comes to Fordham this Sunday at college life. The formal opening of the uptown branch of the University four o'clock. The occasion promises will take place Wednesday with the celebration of the traditional Mass of to be one literally fraught with his- torical significance. Such names as the Holy Ghost. Edgar Allan Poe, Louis Phillippe of Among the eight thousand students PR. WALSH ANNOUNCES France, and James Roosevelt Bay- were four hundred Freshmen in the ley are involved. Uptown School, the number being re- FACULTY ADDITIONS In the presence of a large and ex- stricted according to the rule of re- pectant gathering, which will in- cent years. Father Lawrence A. Father Lawrence A. Walsh, clude many notables, the President's Walsh, S.J., Dean of the Uptown Col- S.J., Dean of the Uptown Col- mother will unveil a bronze tablet, lege, revealed that the new rule has donated to the college by the Ford- tended to increase the number of ap- lege of Fordham University, ham University Alumni Sodality plicants instead of decreasing it, cit- announced the following addi- and located near the door of the ing the fact that over eleven hun- tions to the college faculty; chapel. -

Nomination of Admiral James M. Loy Hearing Committee On

S. Hrg. 108–332 NOMINATION OF ADMIRAL JAMES M. LOY HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENTAL AFFAIRS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED EIGHTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION ON THE NOMINATION OF ADMIRAL JAMES M. LOY TO BE DEPUTY SECRETARY OF HOMELAND SECURITY NOVEMBER 18, 2003 Printed for the use of the Committee on Governmental Affairs ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 91–044 PDF WASHINGTON : 2004 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 0ct 09 2002 10:20 Apr 05, 2004 Jkt 091044 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 C:\DOCS\91044.TXT SAFFAIRS PsN: PHOGAN COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENTAL AFFAIRS SUSAN M. COLLINS, Maine, Chairman TED STEVENS, Alaska JOSEPH I. LIEBERMAN, Connecticut GEORGE V. VOINOVICH, Ohio CARL LEVIN, Michigan NORM COLEMAN, Minnesota DANIEL K. AKAKA, Hawaii ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania RICHARD J. DURBIN, Illinois ROBERT F. BENNETT, Utah THOMAS R. CARPER, Deleware PETER G. FITZGERALD, Illinois MARK DAYTON, Minnesota JOHN E. SUNUNU, New Hampshire FRANK LAUTENBERG, New Jersey RICHARD C. SHELBY, Alabama MARK PRYOR, Arkansas MICHAEL D. BOPP, Staff Director and Chief Counsel JOHANNA L. HARDY, Senior Counsel TIM RADUCHA-GRACE, Professional Staff Member JOYCE A. RECHTSCHAFFEN, Minority Staff Director and Counsel HOLLY A. IDELSON, Minority Counsel JENNIFER E. HAMILTON, Minority Research Assistant AMY B. NEWHOUSE, Chief Clerk (II) VerDate 0ct 09 2002 10:20 Apr 05, 2004 Jkt 091044 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 C:\DOCS\91044.TXT SAFFAIRS PsN: PHOGAN C O N T E N T S Opening statements: Page Senator Collins ................................................................................................