Developing Character Adn Aligning Peersonal Values with Organizational Values in the US Coast Guard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Railway Employee Records for Colorado Volume Iii

RAILWAY EMPLOYEE RECORDS FOR COLORADO VOLUME III By Gerald E. Sherard (2005) When Denver’s Union Station opened in 1881, it saw 88 trains a day during its gold-rush peak. When passenger trains were a popular way to travel, Union Station regularly saw sixty to eighty daily arrivals and departures and as many as a million passengers a year. Many freight trains also passed through the area. In the early 1900s, there were 2.25 million railroad workers in America. After World War II the popularity and frequency of train travel began to wane. The first railroad line to be completed in Colorado was in 1871 and was the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad line between Denver and Colorado Springs. A question we often hear is: “My father used to work for the railroad. How can I get information on Him?” Most railroad historical societies have no records on employees. Most employment records are owned today by the surviving railroad companies and the Railroad Retirement Board. For example, most such records for the Union Pacific Railroad are in storage in Hutchinson, Kansas salt mines, off limits to all but the lawyers. The Union Pacific currently declines to help with former employee genealogy requests. However, if you are looking for railroad employee records for early Colorado railroads, you may have some success. The Colorado Railroad Museum Library currently has 11,368 employee personnel records. These Colorado employee records are primarily for the following railroads which are not longer operating. Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad (AT&SF) Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad employee records of employment are recorded in a bound ledger book (record number 736) and box numbers 766 and 1287 for the years 1883 through 1939 for the joint line from Denver to Pueblo. -

Oi Duck-Billed Platypus! This July! Text © Kes Gray, 2018

JULY 2019 EDITION Featuring buyer’s recommends and new titles in books, DVD & Blu-ray Cats sit on gnats, dogs sit on logs, and duck-billed platypuses sit on …? Find out in the hilarious Oi Duck-billed Platypus! this July! Text © Kes Gray, 2018. Illustrations © Jim Field, 2018. Gray, © Kes Text NEW for 2019 Oi Duck-billed Platypus! 9781444937336 PB | £6.99 Platypus Sales Brochure Cover v5.indd 1 19/03/2019 09:31 P. 11 Adult Titles P. 133 Children’s Titles P. 180 Entertainment Releases THIS PUBLICATION IS ALSO AVAILABLE DIGITALLY VIA OUR WEBSITE AT WWW.GARDNERS.COM “You need to read this book, Smarty’s a legend” Arthur Smith A Hitch in Time Andy Smart Andy Smart’s early adventures are a series of jaw-dropping ISBN: 978-0-7495-8189-3 feats and bizarre situations from RRP: £9.99 which, amazingly, he emerged Format: PB Pub date: 25 July 2019 unscathed. WELCOME JULY 2019 3 FRONT COVER Oi Duck-billed Platypus! by Kes Gray Age 1 to 5. A brilliantly funny, rhyming read-aloud picture book - jam-packed with animals and silliness, from the bestselling, multi-award-winning creators of ‘Oi Frog!’ Oi! Where are duck-billed platypuses meant to sit? And kookaburras and hippopotamuses and all the other animals with impossible-to-rhyme- with names... Over to you Frog! The laughter never ends with Oi Frog and Friends. Illustrated by Jim Field. 9781444937336 | Hachette Children’s | PB | £6.99 GARDNERS PUBLICATIONS ALSO INSIDE PAGE 4 Buyer’s Recommends PAGE 8 Recall List PAGE 11 Gardners Independent Booksellers Affiliate July Adult’s Key New Titles Programme publication includes a monthly selection of titles chosen specifically for PAGE 115 independent booksellers by our affiliate July Adult’s New Titles publishers. -

The Analysis of Gender Markers in Animals Based on the Non-Fiction and Children's Literature

Jiho česká univerzita v Českých Bud ějovicích Pedagogická fakulta Katedra anglistiky Diplomová práce THE ANALYSIS OF GENDER MARKERS IN ANIMALS BASED ON THE NON-FICTION AND CHILDREN'S LITERATURE Anna Lu ňáčková 1. ro čník Učitelství anglického a n ěmeckého jazyka pro 2. stupe ň ZŠ vedoucí diplomové práce Mgr. Ludmila Zemková, Ph.D České Bud ějovice 2011 1 Prohlášení: Prohlašuji, že svoji diplomovou práci jsem vypracovala samostatn ě pouze s použitím pramen ů a literatury uvedených v seznamu citované a použité literatury. Prohlašuji, že v souladu s § 47b zákona č. 111/1998 Sb. v platném zn ění souhlasím se zve řejn ěním své diplomové práce, a to v nezkrácené podob ě elektronickou cestou ve ve řejn ě p řístupné části databáze STAG provozované Jiho českou univerzitou v Českých Bud ějovicích na jejích internetových stránkách, a to se zachováním mého autorského práva k odevzdanému textu této kvalifika ční práce. Souhlasím dále s tím, aby toutéž elektronickou cestou byly v souladu s uvedeným ustanovením zákona č. 111/1998 Sb. zve řejn ěny posudky školitele a oponent ů práce i záznam o pr ůběhu a výsledku obhajoby kvalifika ční práce. Rovn ěž souhlasím s porovnáním textu mé kvalifika ční práce s databází kvalifika čních prací Theses.cz provozovanou Národním registrem vysokoškolských kvalifika čních prací a systémem na odhalování plagiát ů. V Českých Bud ějovicích ……………………………… 30. 4. 2011 Anna Lu ňáčková 2 Touto cestou bych cht ěla pod ěkovat Mgr. Ludmile Zemkové, Ph.D, která byla vedoucí diplomové práce, za její cenné rady, připomínky a ochotu vždy konzultovat problémy týkající se této práce. -

Department of Homeland Security U.S

DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY U.S. Naval Security Station, 3801 Nebraska Avenue, NW., Washington, DC 20393 phone 282–8000 TOM RIDGE, Secretary of Homeland Security; born on August 26, 1945, in Pittsburgh’s Steel Valley; education: earned a scholarship to Harvard University, graduated with honors, 1967; law degree, Dickinson School of Law; military service: U.S. Army; served as an infantry staff sergeant in Vietnam; awarded the Bronze Star for Valor; profession: Attorney; public service: Assistant District Attorney, Erie County, PA; U.S. House of Representatives, 1983–1995; Governor of Pennsylvania, 1995–2001; family: married to Michele; children: Lesley and Tommy; appointed by President George W. Bush as Office of Homeland Security Advisor, October 8, 2001; nominated by President Bush to become the 1st Secretary of Homeland Security on November 25, 2002, and was confirmed by the U.S. Senate on January 22, 2003. OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY Secretary of Homeland Security.—Tom Ridge. OFFICE OF THE DEPUTY SECRETARY Deputy Secretary of Homeland Security.—James Loy. OFFICE OF THE CHIEF OF STAFF Chief of Staff.—Duncan Campbell. MANAGEMENT DIRECTORATE Under Secretary.—Janet Hale. Chief Financial Officer.—Bruce Carnes. Chief Information Officer.—Steven Cooper. Chief Human Capital Officer.—Ronald James. BORDER AND TRANSPORTATION SECURITY DIRECTORATE Under Secretary.—Asa Hutchinson. Assistant Secretary for the Bureau of Immigration and Customs Enforcement.—Michael J. Garcia. Assistant Secretary for Policy and Planning.—Stewart Verdery. Commissioner, Customs and Border Protection.—Robert Bonner. Administrator, Transportation Security Administration.—David Stone (acting). SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY DIRECTORATE Under Secretary.—Charles E. McQueary. 759 760 Congressional Directory INFORMATION ANALYSIS AND INFRASTRUCTURE PROTECTION DIRECTORATE Under Secretary.—Frank Libutti. -

The Old Pangbournian Record Volume 2

The Old Pangbournian Record Volume 2 Casualties in War 1917-2020 Collected and written by Robin Knight (56-61) The Old Pangbournian Society The Old angbournianP Record Volume 2 Casualties in War 1917-2020 Collected and written by Robin Knight (56-61) The Old Pangbournian Society First published in the UK 2020 The Old Pangbournian Society Copyright © 2020 The moral right of the Old Pangbournian Society to be identified as the compiler of this work is asserted in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Design and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, “Beloved by many. stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any Death hides but it does not divide.” * means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior consent of the Old Pangbournian Society in writing. All photographs are from personal collections or publicly-available free sources. Back Cover: © Julie Halford – Keeper of Roll of Honour Fleet Air Arm, RNAS Yeovilton ISBN 978-095-6877-031 Papers used in this book are natural, renewable and recyclable products sourced from well-managed forests. Typeset in Adobe Garamond Pro, designed and produced *from a headstone dedication to R.E.F. Howard (30-33) by NP Design & Print Ltd, Wallingford, U.K. Foreword In a global and total war such as 1939-45, one in Both were extremely impressive leaders, soldiers which our national survival was at stake, sacrifice and human beings. became commonplace, almost routine. Today, notwithstanding Covid-19, the scale of losses For anyone associated with Pangbourne, this endured in the World Wars of the 20th century is continued appetite and affinity for service is no almost incomprehensible. -

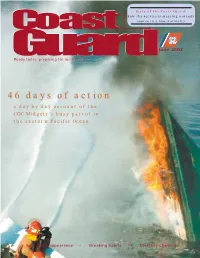

46 Days of Action 46 Days of Action

State of the Coast Guard: how the service is steering a steady CCoastoast course to a new normalcy GuaGuarrdd June 2002 Ready today, preparing for tomorrow 4646 daysdays ofof actionaction a day by day account of the CGC Midgett’s busy patrol in the eastern Pacific Ocean Late Show appearance - Breaking habits - Diversity challenge Heroes The world’s best Coast Guard , DINFOS ALL H EFF A1 J P Lt. Troy Beshears Lt. Cmdr. Brian Moore AST1 John Green AMT1 Michael Bouchard Coast Guard Air Station New Orleans Lt. Cmdr. Moore, Lt. Beshears, AST1 Green and As the helicopter crew returned to the rig and AMT1 Bouchard received a Distinguished Flying prepared to pick up Green, who stayed on the rig to Cross Jan. 20, 2001, for their actions during a rescue coordinate the entire evacuation, the rig exploded into July 5, 2000. a ball of fire that extended from the water The four-man crew was honored for line to 100 feet above the platform. rescuing 51 people from a burning oil rig in the Unsure whether Green was still alive, the crew then Gulf of Mexico. navigated the helicopter into the thick, black column The crew responded to the fire and safely airlifted of smoke to retrieve Green, who was uninjured. 15 people to a nearby platform nine miles from the The Distinguished Flying Cross is the highest fire. The crew evacuated another 36 people to heroism award involving flight that the Coast Guard awaiting boats. can award during peacetime. Coast Guard June 2002 U.S. Department of Transportation Features Guiding Principle: Stand the Watch 8 Diary of action By Lt. -

Nomination of Admiral James M. Loy Hearing Committee On

S. Hrg. 108–332 NOMINATION OF ADMIRAL JAMES M. LOY HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENTAL AFFAIRS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED EIGHTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION ON THE NOMINATION OF ADMIRAL JAMES M. LOY TO BE DEPUTY SECRETARY OF HOMELAND SECURITY NOVEMBER 18, 2003 Printed for the use of the Committee on Governmental Affairs ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 91–044 PDF WASHINGTON : 2004 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 0ct 09 2002 10:20 Apr 05, 2004 Jkt 091044 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 C:\DOCS\91044.TXT SAFFAIRS PsN: PHOGAN COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENTAL AFFAIRS SUSAN M. COLLINS, Maine, Chairman TED STEVENS, Alaska JOSEPH I. LIEBERMAN, Connecticut GEORGE V. VOINOVICH, Ohio CARL LEVIN, Michigan NORM COLEMAN, Minnesota DANIEL K. AKAKA, Hawaii ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania RICHARD J. DURBIN, Illinois ROBERT F. BENNETT, Utah THOMAS R. CARPER, Deleware PETER G. FITZGERALD, Illinois MARK DAYTON, Minnesota JOHN E. SUNUNU, New Hampshire FRANK LAUTENBERG, New Jersey RICHARD C. SHELBY, Alabama MARK PRYOR, Arkansas MICHAEL D. BOPP, Staff Director and Chief Counsel JOHANNA L. HARDY, Senior Counsel TIM RADUCHA-GRACE, Professional Staff Member JOYCE A. RECHTSCHAFFEN, Minority Staff Director and Counsel HOLLY A. IDELSON, Minority Counsel JENNIFER E. HAMILTON, Minority Research Assistant AMY B. NEWHOUSE, Chief Clerk (II) VerDate 0ct 09 2002 10:20 Apr 05, 2004 Jkt 091044 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 C:\DOCS\91044.TXT SAFFAIRS PsN: PHOGAN C O N T E N T S Opening statements: Page Senator Collins ................................................................................................ -

Belfast Festival 2012 Programme

19 october - 4 november 2012 FESTIVAL Programme 02 CONTENTS 50th Ulster Bank Belfast Festival At Queen’s 50th Ulster Bank Belfast Festival At Queen’s WELCOME 03 INTRO 03 C Classical celebrate 04 Com Comedy Anthology 08 D Dance world classy 10 F Film engage 19 Fam Family homegrown 24 T Talks the beautiful game 28 TH Theatre let’s dance 31 TWJP Trad/World/Jazz/Pop headliners 36 SA Sonic Arts delight 40 VA Visual Arts WELCOME INTRODUCTION mexico 48 The 50th Festival. What an exciting season. What a The 50th Belfast Festival at Queen’s presents the re-imagine 50 wonderful achievement. opportunity to reflect on what has been achieved over In 1961 a group of young Queen’s students organised the the years and to remember what makes this cultural graphic grrRls 54 first arts festival at the University. Modest in scope compared extravaganza so special. It is breath-taking to consider the to today, it nonetheless shone with ambition and it had a number of people who, over the last five decades, have innovate 56 sense of purpose - only the best will do. played their part in creating Festival’s cultural legacy. From those early days the Queen’s Festival - now the Ulster From artists and performers, venues and audiences, inspire 61 Bank Belfast Festival at Queen’s - has indeed been bringing volunteers and staff through to our patrons and supporters us the best, and in doing so it has placed this city firmly on all have helped Festival on its journey and ensured that it 50 shades of green 64 the map as a centre of cultural importance. -

Cornelius Ryan Collection of World War II Papers, Mahn Center for Archives and Special Collections, Ohio University

Cornelius Ryan Collection of World War II Papers, Mahn Center for Archives and Special Collections, Ohio University A Bridge Too Far Inventory List First published by Simon & Schuster in 1974. A Bridge Too Far has been translated into Chinese, Czech, Dutch, French, German, Hebrew, Hungarian, Indonesian, Italian, Japanese, Malay, Persian, Polish, Romanian, Serbo-Croatian, Slovenian, Spanish, Swedish, and Turkish. A movie version appeared in 1977, directed by Richard Attenborough and starring Dirk Bogarde, James Caan, Michael Caine, Sean Connery, Edward Fox, Anthony Hopkins, Gene Hackman, Hardy Krüger, Laurence Olivier, Robert Redford, and Maximilian Schell. Alden Library has both VHS and DVD versions of the movie. Table of Contents Initial Research .........................................................................................................................................................................2 Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force ................................................................................................................. 7 American Forces ......................................................................................................................................................................8 British Forces .........................................................................................................................................................................45 Canadian Forces .....................................................................................................................................................................86 -

Qilom Cloud Shadowing Schools

•?$••&<• C* rs, how do vets fuel about Vietnam? See page A-6. To subscribe, call (800) 300-9321 he^festfielPhursday, May 23, 1996 d Record A Forbes Newspaper 5p j Briefs Fashion show qilOM cloud shadowing schools Tha Parent's CWb of the WeatfWH Neighborhood Coun- cil will sponsor "Changing State plan would force voter approval of spending above 'norm' laoss." its fin* spring fashion show and buffet 94 pm Satur- constitutionally mandated "thorough and ef- oobson said she had not yet determined going tobt hard to get voters to understand ; June 8 at the Wsstfiekt Y, RB0ORD ficient" education. The schools will be al- what the new plan would mean to Westfield. it differently," h« said. CtarkSt lowad to spend more than the state man- The spending amounts to be set by the If the public voted down the extra spend- Tickets an $10 for adults and The Westfield Public School District k dates, but to do so, will have to seek voter state, said Dr. Smith, are $0,720 per pupil for ing, the mayor and Tbwn Council would sort $9 for children jnunis than 12. bracing for a storm from the south — a approval. elementary schools, $7,526 per pupil for mid- out the budget tangle. : Proceeds benefit children's twister from Trenton to be specific. •There are some good things in the plan," dle schools and $8,640 per pupil for high In setting the financial limits, the state set laduoatkm programs. Must will The state Board of ^duration's new school said Dr. Smith. "I believe defining a thor- schools. -

Confessions of a Railroad Signalman (1908)

CONFE OF A JAMES O. FAGAN %1° Pv CONFESSIONS OF A RAILROAD SIGNALMAN Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2007 with funding from Microsoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/confessionsofraiOOfagauoft v Ik u|K& * v. ?i,;"yirq/t CONFESSIONS OF A RAILROAD SIGNALMAN BY J. O. FAGAN WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BOSTON AND NEW YORK HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY (3TI)e fiivjcrs'i&c press Cambridge 1908 COPYRIGHT I908 BY J. O. FAGAN ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Published October iqo& CONTENTS I. A Railroad Man to Railroad Men i II. The Men 26 III. The Management 47 IV. Loyalty 69 V. The Square Deal 95 VI. The Human Equation 118 VII. Discipline 149 ILLUSTRATIONS A Typical Smash-Up Frontispiece A Head-On Collision 26 A Yard Wreck 52 A Typical Derailment 82 A Rear-End Collision 112 What Comes from a Misplaced Switch 132 Down an Embankment in Winter 150 The Aftermath 176 Acknowledgment is due to the proprietors of Collier's Weekly and of the Boston Herald for their courteous loan of the photo- graphs from which the above illustrations have been engraved. CONFESSIONS OF A RAILROAD SIGNALMAN A RAILROAD MAN TO RAILROAD MEN Considering the nature and intent of the fol- lowing essays on the safety problem on American railroads, some kind of a foreword will not be out of place. As much as possible I wish to make this foreword a personal presentation of the subject. But in order to do this in a satisfactory manner, it will be necessary to take a preliminary survey of the situation and of the topics in which we, as railroad employees, are all personally interested. -

Senate Hearings Before the Committee on Appropriations

S. HRG. 109–195 Senate Hearings Before the Committee on Appropriations Department of Homeland Security Fiscal Year 2006 109th CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION H.R. 2360 DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY NONDEPARTMENTAL WITNESSES Department of Homeland Security, 2006 (H.R. 2360) S. HRG. 109–195 DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY APPROPRIATIONS FOR FISCAL YEAR 2006 HEARINGS BEFORE A SUBCOMMITTEE OF THE COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED NINTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION ON H.R. 2360 AN ACT MAKING APPROPRIATIONS FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF HOME- LAND SECURITY FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDING SEPTEMBER 30, 2006, AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES Department of Homeland Security Nondepartmental witnesses Printed for the use of the Committee on Appropriations ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.gpoaccess.gov/congress/index.html U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 99–863 PDF WASHINGTON : 2005 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi, Chairman TED STEVENS, Alaska ROBERT C. BYRD, West Virginia ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania DANIEL K. INOUYE, Hawaii PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico PATRICK J. LEAHY, Vermont CHRISTOPHER S. BOND, Missouri TOM HARKIN, Iowa MITCH MCCONNELL, Kentucky BARBARA A. MIKULSKI, Maryland CONRAD BURNS, Montana HARRY REID, Nevada RICHARD C. SHELBY, Alabama HERB KOHL, Wisconsin JUDD GREGG, New Hampshire PATTY MURRAY, Washington ROBERT F. BENNETT, Utah BYRON L. DORGAN, North Dakota LARRY CRAIG, Idaho DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas RICHARD J. DURBIN, Illinois MIKE DEWINE, Ohio TIM JOHNSON, South Dakota SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas MARY L.