Iranians and Their Ancestors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Code Name: Immortal

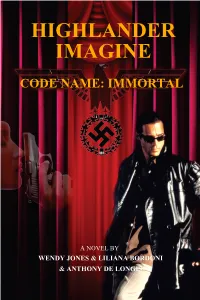

HIGHLANDER IMAGINE CODE NAME: IMMORTAL A NOVEL BY WENDY JONES & LILIANA BORDONI & ANTHONY DE LONGIS FICTION: ACTION & ADVENTURE/ROMANCE/HISTORICAL "This train can't take a Quickening, it will be destroyed! How many people will die because of us?" IT'S SPY VS SPY with Duncan MacLeod of the Clan MacLeod caught in the middle. When Connor suddenly disappears, Annelise’s desperate plea for Duncan to help her find him pulls the Highlander into a deadly game of cat and mouse. Soon, Duncan is face-to-face with the head of the Hunters’ organization and their darkest secrets. Master of the sword, Anthony De Longis weaves a deadly tale of suspense, intrigue and no-holds-barred sword fights between the Mac Leods and those seeking their Quickenings. This work was fully authorized by Davis-Panzer Productions and Studiocanal Films Ltd; however the content is wholly an RK Books original fan creation. “Since when do Immortals need an excuse to kill Watchers?” Annelise snapped. “It was just evening the score for what those people do to you people. I would’ve done the same,” she finished, coldly. Aghast, Duncan did a double take. “Kill Watchers—what are you saying? What score are you talking about?” “I know now who’s responsible for what happened to my brother,” she continued. “Connor promised he would help me free him—he’s on his way there now, but I know it’s a trap. You’ve got to help me, Duncan. Take me to Connor before it is too late for both of them.” Follow Solo Highlander Imagine Code Name: Immortal An RK Books production www.RK-books.com ISBN: 978-0-9777110-6-2 Copyright © January 4, 2018 by Wendy Lou Jones Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data Jones, Wendy Lou Highlander Imagine: Code Name Immortal by Wendy Lou Jones Fiction: Historical │ Mystery Detective / Historical │ Romance / Action & Adventure Library of Congress Control Number: 2017963943 All rights reserved Highlander Imagine Series This work was fully authorized by Davis-Panzer Productions and Studiocanal Films Ltd; however the content is wholly an RK Books original fan creation. -

Darkest Knight Illumination

Darkest Knight Illumination Darkness. It is not merely the absence of light. For one, it is a permanent state of being. Some claim that a moonless night is the poetic epitome of darkness. They are wrong. Some poor souls who have been trapped underground tell of the oppressive, velvet blackness, of how they whimpered with fear as the encroaching darkness swallowed their sanity within hours. They are closer. There is one being alive who truly knows what darkness is. Has embraced it, welcomed it, even accepted it into his being. He could hardly do otherwise. For longer than any normal man could imagine, he has lain alone, in a clay coffin the precise size and dimensions of his body. For an eternity he has been held in stasis, as the rigid slate around him prevented him from moving; even prevented him from breathing. Not that, to this being, being prevented from breathing was anything more than an annoyance. His ancient heart still beat strongly, exactly as strongly as it had for thousands of years, pumping blood with no oxygen around his body. His muscles had not atrophied, nor would they, no matter how long he remained trapped in the eternal darkness. One thing, and one thing alone allowed this being to focus his mind, to keep the hounds of insanity at bay. Hatred. And with it, a deep, smouldering desire for revenge. Suddenly, like the birth of a star, the earth shuddered, and the darkness finally broke. The bright yellow vehicle drew to a halt outside an antiques store on Hudson Street. -

White Rabbit

Dargelos White Rabbit A Chronicle of the Old Dead Guys Bound in Leather Press Chicago Glen Ellyn Dedicated to the memory of Bill Reynolds Long ago, it must be, I have a photograph. Preserve your memories, they’re all that’s left you. Paul Simon, Bookends Theme 2 Introduction If you remember the sixties, you weren’t there. For those old enough to remember the Old Dead Guys, the name alone is synonymous with an entire era. For me, at least, they summed up the sixties in a way few other bands could do, and even though they never became as widely known as bands like the Beatles or the Rolling Stones, I believe that had they not broken up when they did, they might well have achieved the fame they deserved within a very short time. This is not an “official” biography of the group by any means, though I did have access to a great deal of material that belonged to band members, and much which has been out of circulation for nearly three decades. For that I would like to thank my sources, most of whom prefer to remain anonymous. However, two of them I can thank publicly: Michael Altman was a great help to me in compiling and interpreting this material. He gave me access to unpublished material which has shed a lot of new light on the group and its members; in order to be clear on exactly what it is you’re reading, please see Michael’s note which follows this introduction. Sydney Ember, who has been incredibly kind and supportive of this effort, gave me complete access to his superb collection of ODG memorabilia as well as sharing a great many memories of the group with me. -

Iranians and Greeks After 90 Years: a Religious History of Southern Russia in Ancient Times*

doi: 10.2143/AWE.10.0.2141816 AWE 10 (2011) 75-159 IRANIANS AND GREEKS AFTER 90 YEARS: A RELIGIOUS HISTORY OF SOUTHERN RUSSIA IN ANCIENT TIMES* CASPAR MEYER Abstract This introductory essay places Rostovtzeff’s interpretative model of northern Black Sea archaeology in the context of contemporary historical imagination in Russia and Europe. The discussion focuses in particular on Rostovtzeff’s approach to Graeco-Scythian metal- work, as pioneered in his 1913 article on ‘The conception of monarchical power in Scythia and on the Bosporus’, and the possibilities which religious interpretation of the objects’ figured scenes offered in developing the narrative of cultural fusion between Orientals and Occidentals best known in the West from his Iranians and Greeks in South Russia (1922). The author seeks to bring out the teleological tendencies of this account, largely concerned with explaining Russia’s historical identity as a Christian empire between East and West. I think that it is good for people to read Rostovtzeff, even where he isn’t quite up-to-date. (C. Bradford Welles) Western specialists of northern Black Sea archaeology have a particular reason to welcome the recent proliferation of print-on-demand publishing. Not so long ago, the most influential synthesis of the region’s history and archaeology in the Classi- cal period, Michael Ivanovich Rostovtzeff’s Iranians and Greeks in South Russia (Oxford 1922), realised exorbitant prices on the antiquarian book market, beyond the reach of most students and many university academics. Its status as a biblio- phile treasure was assured by the fact that, in contrast to Rostovtzeff’s other major works, Iranians and Greeks had never been reprinted by his preferred publisher, Clarendon Press at the University of Oxford. -

Fantastic Beasts of the Eurasian Steppes: Toward a Revisionist Approach to Animal-Style Art

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2018 Fantastic Beasts Of The Eurasian Steppes: Toward A Revisionist Approach To Animal-Style Art Petya Andreeva University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian Studies Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Andreeva, Petya, "Fantastic Beasts Of The Eurasian Steppes: Toward A Revisionist Approach To Animal- Style Art" (2018). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2963. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2963 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2963 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Fantastic Beasts Of The Eurasian Steppes: Toward A Revisionist Approach To Animal-Style Art Abstract Animal style is a centuries-old approach to decoration characteristic of the various cultures which flourished along the urE asian steppe belt in the later half of the first millennium BCE. This astv territory stretching from the Mongolian Plateau to the Hungarian Plain, has yielded hundreds of archaeological finds associated with the early Iron Age. Among these discoveries, high-end metalwork, textiles and tomb furniture, intricately embellished with idiosyncratic zoomorphic motifs, stand out as a recurrent element. While scholarship has labeled animal-style imagery as scenes of combat, this dissertation argues against this overly simplified classification model which ignores the variety of visual tools employed in the abstraction of fantastic hybrids. I identify five primary categories in the arrangement and portrayal of zoomorphic designs: these traits, frequently occurring in clusters, constitute the first comprehensive definition of animal-style art. -

Highlander (The Movies) Jump Version 0.02 (Jumpchain Compliant) by Orion Ultor and Abraxesanon

Highlander (The Movies) Jump Version 0.02 (Jumpchain Compliant) By Orion Ultor and AbraxesAnon Highlander: “From the dawn of time we came; moving silently down through the centuries, living many secret lives, struggling to reach the time of the Gathering; when the few who remain will battle to the last. No one has ever known we were among you... until now.” -Juan Sánchez Villa-Lobos Ramírez In 1985, an Immortal known as Connor MacLeod living in New York, under the guise of an antiques dealer is challenged by another immortal in a parking garage. Some police detectives get involved and history's tale of a man who lived for longer than his time begins to be told. 2024, an alternate dimension, the ozone layer has become depleted. Connor MacLeod. Immortals are aliens from the planet Zeist? Wait, that was taken out of the Director's cut and ignored by subsequent movies? Okay so the only pseudo-canonical event is MacLeod facing a powerful immortal named Katana and killing him and fighting the power to take down an artificial ozone layer since Earth has replenished itself from an Evil Shield Corporation. Good luck Understanding any of this. Back in 1994, an Alternate dimension’s sequel to the first Highlander movie events is a walk down memory lane as Connor MacLeod deals with his retirement from the Game being interrupted by three Immortals, lead by Kane, who, due to being stuck under a heavy rock in a cave after they tried to take an Immortal Japanese sorcerer’s life come after him. -

Series Renewal & Cancellation Update

<Vo~mLOiJL <:NlunbuJO SERIES RENEWAL & CANCELLATION UPDATE T/iDLE OF CONTENTS It's our first sign of age - a series renewal update/new series 2 Voyages"Cthe Star Trek: Voyager episode ft report was the first (and only) article in LogBook's first issue last guide ~Faces, Jetrel and Learning Curve August. 3 Next Generation - the final season review Fox has officially cancelled VR.5, but this fall, keep an eye out for their new series Space, created by the team of Glen Morgan and continues with First Born, Bloodlines, James Wong who previously served as co-executive producers of The Emergence and Preemptive Strike. XiFites; the show follows the adventures of three young cadets who 4 News Tidbits: Dorn. discs, the Doctor. and a must grow up on the front line when humanity stumbles into a death; To The the DS9 review column bloody war upon its first contact with alien life in the distant future. Nin.es ~ Morgan Weisser, Rodney Rowland and Kristin Cloke have been cast 5 Inside Them - is Godzilla a natural force? as the series leads; David Nutter, also an X'Files veteran, directs the 6 Highlander:'howdothernovies and TV series opening installment. compare? (And whose bright idea was it to , USA Network has canned William Shatner's TekWar series, though it may be revived by a Canadian production outfit. Speaking turn it into a cartoon, ,anyway?) of Shatner, he has apparently for the first time given his blessing to 7 Ikwv')view§ - Clarke·s.Th~ Hammf!r QfGod one of the new Trek series: according to Gary L. -

IMMORTAL: the QUICKENING 20TH ANNIVERSARY EDITION Foreword

IMMORTAL: THE QUICKENING 20TH ANNIVERSARY EDITION Foreword Highlander: The Gathering was written back possible, and to clear up some things about in 1993 and is one of the most loved fan Immortals. I also choose to ignore the bad supplements. Unfortunately for us some 20 Highlander movies, and to keep the good fluff in years have passed since edition 2.5 was made, check, while preserving the original game's and 3rd edition never came out. With the rise of concepts. This means the game's Immortals are the 20th anniversary editions of Vampire, slightly different than the ones in series and Werewolf, and Mage, I thought it would be a movies. good idea to redo the rules for modern times. "Immortal: The Gathering 20th Anniversary Some of the things changed in this are the Edition” is compiled from Hank Driskill and John virtues system. Originally Immortals didn't have Gavigan’s “Highlander: The Gathering” and virtues like humans, however with the creation Mark Antill’s “The Highlander Players Guide.", of new editions of Vampire, this changed, and R's Revised Edition. This net supplement Highlander didn't. So I have introduced the would not be possible without their hard work. concept of Dark Quickening, which functions This version brings together the best similarly to Torment from Demon, but transfers elements of the work of these gentlemen into between Immortals after a death. This has one sourcebook. It also places the supplement added a sense of morality that is well known to in step with the 20th Anniversary Edition books, the World of Darkness, and now Immortals are both mechanically and thematically. -

Publication on Frozen Tombs of the Altai Mountains

PRESERVATIONPRPRESERVATIONPROFOF THETTHETHHESEREESERE FROZENFRFROZENFROZENOOZENZEN TOMBSTOMBSVVAA OFOFTIONTION THETHE ALTAIALTAI MOUNTAINSMOUNTAINS PRESERVATIONPRPRESERVATIONPROFOF THETTHETHHESEREESERE FROZENFRFROZENFROOZENZEN TOMBSTTOMBSTOOMBSVATIONMBSVATION OFOF THETHE ALTAIALTAI MOUNTAINSMOUNTAINS 5 Staff Head in the Form of Large Gryphon’s Head with a Deer’s Head in its Beak.Wood and leather; carved. H. 35 cm Pazyryk Culture. 5th century bc. Inv. no. 1684/170. © The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg. The views expressed in the articles contained in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of UNESCO. Table of Contents Foreword Koïchiro Matsuura 9 Introduction J. Han 11 Maps and Chronology 16–17 CHAPTER I SCYTHIANS IN THE EURASIAN STEPPE AND THE PLACE OF THE ALTAI MOUNTAINS IN IT The Scythians: Nomadic Horsemen of the Eurasian Steppe H. Parzinger 19 The Frozen Scythian Burial Complexes of the Altai Mountains: Conservation and Survey Issues V.I. Molodin 25 Culture and Landscape in the High Altai E. Jacobson-Tepfer 31 Ancient Altai Culture and its Relationship to Historical Asian Civilizations H. P. Francfort 35 The Silk Roads and the Road of the Steppes: Eurasia and the Scythian World P. Cambon 41 C HAPTER II UNESCO PROJECT PRESERVATION OF FROZEN TOMBS OF THE ALTAI MOUNTAINS Background to UNESCO Preservation of the Frozen Tombs of the Altai Mountains Project and Perspectives for Transboundary Protection through the World Heritage Convention J. Han 49 UNESCO-Sponsored Field Campaigns in the Russian and Kazakh Altai J. Bourgeois and W. Gheyle 55 Climate Change and its Impact on the Frozen Tombs of the Altai Mountains S. Marchenko 61 CHAPTER III CHALLENGE FOR CONSERVATION AND DEVELOPMENT The Altai: Heartland of Asia Y.P. -

Burial Mounds of Scythian Elites in the Eurasian Steppe: New Discoveries

Journal of the British Academy, 5, 331–355. DOI https://doi.org/10.5871/jba/005.331 Posted 29 November 2017. © The British Academy 2017 Burial mounds of Scythian elites in the Eurasian steppe: New discoveries Albert Reckitt Archaeological Lecture read 1 December 2016 HERMANN PARZINGER Fellow of the Academy Abstract: This article is dedicated to the phenomena called ‘kurgans’, the monumental burial mounds of riding nomads of the Scythian period. Kurgans were first investi- gated in southern Ukraine and southern Russia, the core area of Scythian tribes according to Herodotus. East of the Ural Mountains, however, the kurgans are less known, as only very few of these monumental burial mounds have been decently exca- vated. In the last 20 years, however, several Russian–German projects under the author’s leadership have been dedicated to a better understanding of monumental kurgans in the steppe belt of Eurasia—Kazakhstan, southern Siberia, the Ural region and the northern Caucasus—contributing an enormous amount of new information about the complexity of these burial monuments. It has become clear that these elite burial monuments are not only important for rich funerary goods but also for the complex structure of the kurgans themselves, which only can be fully understood if they are considered as rituals which became architecture. Keywords: Eurasia, steppe belt, Scythians, kurgans, monumentality, elites, riding nomads. The relics of ancient rider-nomads of the 8th–3rd centuries BC, the older Iron Age, hold a special position in the study of the cultural development of the Eurasian steppe belt, for in them a clear social stratification can be recognised for the first time in the history of this area. -

Only with a Highlander Free

FREE ONLY WITH A HIGHLANDER PDF Janet Chapman | 384 pages | 02 Dec 2005 | SIMON & SCHUSTER | 9780743486323 | English | New York, United States Only With a Highlander | Janet Chapman Highlander is a fantasy action - adventure film directed by Russell Mulcahy and based on a story by Gregory Widen. The film chronicles the climax of an ages-old war between immortal warriors, depicted through interwoven past and present-day Only with a Highlander. Immortals wage a secret war, fighting each other until the last few remaining will meet at the Gathering to fight for the Prize. Nevertheless, it became a cult film and inspired film sequels and television spin-offs. The tagline, "There can be only one", has carried on into pop culture. After a sword duel, MacLeod beheads Fasil and experiences the Quickening —the result of a one immortal killing another— a powerful energy release that affects the immediate surroundings, destroying many cars. After Connor hides his sword Only with a Highlander the garage's ceiling, NYPD officers detain him for murder, later releasing him due to lack Only with a Highlander evidence. Connor's history is revealed through a series of flashbacks. The Frasers are aided by the Kurgan the last of the Kurgan tribes in exchange for his right to slay Connor. In battle, the Kurgan stabs Connor fatally, but is driven off before he can decapitate him. Connor makes a complete recovery and is accused of witchcraft. The clan wishes to kill him, but chieftain Angus mercifully exiles him. Banished, he wanders the highlands, becoming a Only with a Highlander and marrying a woman named Heather. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Karma with a Grudge by Reno Macleod Karma with a Grudge by Reno Macleod

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Karma With A Grudge by Reno MacLeod Karma With A Grudge by Reno MacLeod. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 65897c0d69dcc3cf • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. Series / Highlander. Highlander: The Series is the 1992-1997 series inspired by the popular Highlander film franchise. It stars British actor Adrian Paul as Duncan MacLeod, the younger kinsman of the movies' Connor MacLeod (Christopher Lambert), who passes the torch in the pilot episode. The series was a French-Canadian co-production, which resulted in half of it being filmed in the U.S. and Vancouver and the other half in Paris. The exceptions were Season Six and the Spin-Off series (see below), which were filmed entirely in Paris. The central premise was a bit predictable at times: Duncan would encounter an old immortal enemy, or an immortal friend with someone chasing after them, and the episode would end with Duncan battling his opponent and beheading them.