A Mexican Cossack in Southern California

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proceedings Op the Twenty-Third Annual Meeting Op the Geological Society Op America, Held at Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, December 21, 28, and 29, 1910

BULLETIN OF THE GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF AMERICA VOL. 22, PP. 1-84, PLS. 1-6 M/SRCH 31, 1911 PROCEEDINGS OP THE TWENTY-THIRD ANNUAL MEETING OP THE GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OP AMERICA, HELD AT PITTSBURGH, PENNSYLVANIA, DECEMBER 21, 28, AND 29, 1910. Edmund Otis Hovey, Secretary CONTENTS Page Session of Tuesday, December 27............................................................................. 2 Election of Auditing Committee....................................................................... 2 Election of officers................................................................................................ 2 Election of Fellows................................................................................................ 3 Election of Correspondents................................................................................. 3 Memoir of J. C. Ii. Laflamme (with bibliography) ; by John M. Clarke. 4 Memoir of William Harmon Niles; by George H. Barton....................... 8 Memoir of David Pearce Penhallow (with bibliography) ; by Alfred E. Barlow..................................................................................................................... 15 Memoir of William George Tight (with bibliography) ; by J. A. Bownocker.............................................................................................................. 19 Memoir of Robert Parr Whitfield (with bibliography by L. Hussa- kof) ; by John M. Clarke............................................................................... 22 Memoir of Thomas -

Turkmenistan Oil and Gas

Pre-Caspian Pipe- Central Turkmenistan Oil and Gas Map line (active) Turkmenistan Oil and Gas Map Asia-Center Pre-Caspian Pipe- Kazakhstan Gas Pipeline line (planned) Legend (to Russia) National Capital Uzbekistan Velayat Capital Population Center Sarygamysh Koli Dashovuz International Boundary Block Velayat Border 1 Garabogaz River or Canal 7 2 Oil/ Gas Pipeline 8 Transcaspian 3 Kara-Bogaz-Gol Pipeline Under Construction 9 Bay Gas Pipeline 4 DASHOVUZ Proposed Pipeline 10 VELAYAT 5 Oil/Gas Field 11 6 Gyzylgaya Protected Area 12 LEBAP Port Ufra BALKAN VELAYAT Turkmenbashi Belek VELAYAT Refinery 13 14 Cheleken Balkanabat Belek-Balkanabat- c 2011 CRUDE ACCOUNTABILITY 15 Serdar Pipeline 16 Aladzha Turkmenistan-China 24 Yerbent 17 Gas Pipeline 25 Gumdag 18 Serdar Turkmenabat 26 AHAL 19 East - West Karakum Canal VELAYAT 27 20 Ogurchinsky Pipeline Amu Darya River Island 28 29 21 22 Okarem Ashgabat 30 23 Magdanli Kerki 31 Mary Esenguly Bayramaly Caspian Tejen Sea Korpeje-Kordkuy Pipeline Iran South Yolotan- Osman Field Saragt This map is a representation of Turkmenistan’s major oil and gas fields and transport infrastructure, including ports and Dovletabat MARY Afghanistan pipeline routes, as of February 2011. As the world turns its attention to Turkmenistan’s vast petroleum reserves, more Field VELAYAT precise details about the fields are sure to become known, and—over time—it will become clear which of the proposed and hotly debated pipelines comes into existence. For now, this map demonstrates where the largest reserves are Dovletabat - located, and their relationship to population centers, environmentally protected areas, key geographical features (the Sarakhs - Caspian Sea, the Kopet Dag Mountain Range, and the Karakum Desert) and neighboring countries. -

Proceedings of the Thirty-Seventh Annual Meeting of the Geological

BULLETIN OF THE GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF AMERICA PROCEEDINGS OF THE THIRTY-SEVENTH ANNUAL MEET ING OP THE GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF AMERICA, HELD AT ITHACA, NEW YORK, MONDAY-WEDNESDAY, DECEM BER 29-31, 1924. Charles P. Berkey, Secretary CONTENTS Page Session of Monday morning, December 2 9 . .. .................................................... 5 Report of the Council...................................................................................... 5 President’s report......................................................... ............................ 5 Secretary’s report...................................................................................... 7 Treasurer’s report....................................................................................... 9 Editor’s report............................................................................................. 10 Election of Auditing Committee.................................................................. 12 Election of officers, representatives, Correspondents, and Fellows.. 12 Necrology............................................................................................................... 14 Memorials.......................................................................................................... ... 14 Memorial of John Casper Branner (with bibliography) ; by R. A. F. Penrose, Jr............................................................................. 15 Memorial of Raphael Pumpelly (with bibliography) ; by Bailey Willis............... ........................................................................................ -

William Morris Davis Brief Life of a Pioneering Geomorphologist: 1850-1934 by Philip S

VITA William Morris Davis Brief life of a pioneering geomorphologist: 1850-1934 by PhiliP S. Koch Naught looks the same for long… Waters rush on, make valleys where once stood plains; hills wash away to the sea. Marshland dries to sand, while dry land becomes stagnant, marshy pool. From Nature, springs erupt or are sealed; from earthquakes, streams burst forth or vanish. n Metamorphoses, the Roman poet Ovid, echoing Pythagoras, al- ludes to geomorphology: the study of the forms taken by the Iearth’s surface, and what causes them. Almost 19 centuries later, William Morris Davis, S.B. 1869, devised a clear, concise, descrip- tive, and idealized model of landscape evolution that revolutionized and in many ways created this field of study. Born into a prominent Philadelphia Quaker family, Davis studied geology and geography at Harvard’s Lawrence Scientific School and then joined a Harvard-sponsored geographic-exploration party to the Colorado Territory, led by the inaugural Sturgis-Hooper profes- sor of geology, Josiah Dwight Whitney. Wild stories had circulated since soon after the Louisiana Purchase about Rocky Mountain peaks 18,000 feet or higher. The Harvard expedition set out to investigate, and found none, but they did find “’14ers” (14,000-plus feet). Among these, the expedition members surveyed, named, and made two first- river valleys locally decrease the growing recorded summitings in the “Collegiate Peaks,” designating the tall- elevation differences between “uplands” est in the group Mount Harvard (honoring their sponsor), and the and “base-level” caused by uplift. In “Ma- second tallest Mount Yale (honoring Whitney’s alma mater). -

THE LOST INDUSTRY: the TURKMEN MARINE FISHERY the Report

THE LOST INDUSTRY: THE TURKMEN MARINE FISHERY The report DEMOCRATIC CIVIL UNION OF TURKMENISTAN With the support of The National Endowment for Democracy (NED), USA 2015 [email protected] THE LOST INDUSTRY: THE TURKMEN MARINE FISHERY Contents HISTORICAL BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................. 2 MARINE FISHERY IN THE SOVIET ERA ................................................................................................. 4 MARINE FISHERY OF TURKMENISTAN IN THE POST-SOVIET PERIOD ................................................. 7 ORGANIZATIONAL AND TECHNICAL CAUSES OF THE DEGRADATION OF THE MARINE FISHERY ..... 12 NATURAL AND ANTHROPOGENIC PROBLEMS OF THE CASPIAN SEA ............................................... 19 PROSPECTS OF MARINE FISHERY IN TURKMENISTAN ...................................................................... 20 1 THE LOST INDUSTRY: THE TURKMEN MARINE FISHERY THE LOST INDUSTRY: the Turkmen marine fishery HISTORICAL BACKGROUND Turkmens living in the South-Eastern shore of the Caspian sea – in the current cities Turkmenbashi, Khazar, Garabogaz 1and etraps Turkmenbashi and Esenguly2 – consider themselves the indigenous inhabitants of these places who settled in seaside thousands of years ago. According to the main occupation of their ancestors they call themselves hereditary fishermen and are proud of their fishing origins, especially in the coastal towns. It is confirmed by their way of life, daily graft, houses, cuisine, crafts, -

49370-002: National Power Grid Strengthening Project

Initial Environmental Examination Final Report Project No.: 49370-002 October 2020 Turkmenistan: National Power Grid Strengthening Project Volume 4 Prepared by the Ministry of Energy, Government of Turkmenistan for the Asian Development Bank. The Initial Environmental Examination is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. 49370-002: TKM TKM Power Sector Development Project 81. Out of these IBAs, eight IBAs are located close to phase I Transmission line alignments. Four IBAs are located close to proposed Gurtly (Ashgabat) to Balkanabat Transmission line. And four falls close to existing Sardar (West) to Dashoguz Transmission line. No IBA falls close to Dashoguz-Balkan Transmission line. The view of these IBAs with respect to transmission alignment of phase I are shown at Figure 4.17. 82. There are 8 IBAs along phase II alignment. Two IBAs, i.e. Lotfatabad & Darregaz and IBA Mergen is located at approx 6.0 km &approx 9.10 km from alignment respectively. The view of these IBAs with respect to transmission alignment of phase II is shown at Figure 4.18. : Presence of Important Bird Areas close to Proposed/existing -

Geological Survey

imiF.NT OF Tim BULLETIN UN ITKI) STATKS GEOLOGICAL SURVEY No. 115 A (lECKJKAPHIC DKTIOXARY OF KHODK ISLAM; WASHINGTON GOVKRNMKNT PRINTING OFF1OK 181)4 LIBRARY CATALOGUE SLIPS. i United States. Department of the interior. (U. S. geological survey). Department of the interior | | Bulletin | of the | United States | geological survey | no. 115 | [Seal of the department] | Washington | government printing office | 1894 Second title: United States geological survey | J. W. Powell, director | | A | geographic dictionary | of | Rhode Island | by | Henry Gannett | [Vignette] | Washington | government printing office 11894 8°. 31 pp. Gannett (Henry). United States geological survey | J. W. Powell, director | | A | geographic dictionary | of | Khode Island | hy | Henry Gannett | [Vignette] Washington | government printing office | 1894 8°. 31 pp. [UNITED STATES. Department of the interior. (U. S. geological survey). Bulletin 115]. 8 United States geological survey | J. W. Powell, director | | * A | geographic dictionary | of | Ehode Island | by | Henry -| Gannett | [Vignette] | . g Washington | government printing office | 1894 JS 8°. 31pp. a* [UNITED STATES. Department of the interior. (Z7. S. geological survey). ~ . Bulletin 115]. ADVERTISEMENT. [Bulletin No. 115.] The publications of the United States Geological Survey are issued in accordance with the statute approved March 3, 1879, which declares that "The publications of the Geological Survey shall consist of the annual report of operations, geological and economic maps illustrating the resources and classification of the lands, and reports upon general and economic geology and paleontology. The annual report of operations of the Geological Survey shall accompany the annual report of the Secretary of the Interior. All special memoirs and reports of said Survey shall be issued in uniform quarto series if deemed necessary by tlie Director, but other wise in ordinary octavos. -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory -- Nomination Form

THEME: Americans at Work Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) SUBTHEME: " ence and Invention" UNITED STATES DEPART . .cNT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS I NAME HISTORIC William Morris Davis House AND/OR COMMON 17 Francis Street LOCATION STREET & NUMBER 17 Francis Street _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Cambridge VICINITY OF 8th STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Massachusetts 75 Middlesex 017 CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT __PUBLIC ^.OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM X_BUILDING(S) ^—PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL .^PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS —YES. RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC _BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION X.NO —MILITARY —OTHER (OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Francis M. shea STREET & NUMBER 17 Francis Street CITY, TOWN STATE Cambridge _ VICINITY OF Massachusetts (LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. Middlesex Registry of Deeds Southern District REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC STREET & NUMBER 3rd and Ottis Streets CITY. TOWN STATE Cambridge Massachusetts REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE None DATE — FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY __LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY. TOWN STATE DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE x .^EXCELLENT _DETERIORATED _UNALTERED ^.ORIGINAL SITE _GOOD _RUINS _ALTERED _MOVED DATE- _FAIR (unrestored) _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The William Morris Davis House in Cambridge, Massachusetts, is a frame, 2h story gabled roof house with a gambreled roof wing. The exterior is sheathed in shingles. The main entrance is located on the side of the house and there is also a rear entrance. -

The EERI Oral History Series

CONNECTIONS The EERI Oral History Series Robert E. Wallace CONNECTIONS The EERI Oral History Series Robert E. Wallace Stanley Scott, Interviewer Earthquake Engineering Research Institute Editor: Gail Hynes Shea, Albany, CA ([email protected]) Cover and book design: Laura H. Moger, Moorpark, CA Copyright ©1999 by the Earthquake Engineering Research Institute and the Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to the Earthquake Engineering Research Institute and the Bancroft Library of the University of California at Berkeley. No part may be reproduced, quoted, or transmitted in any form without the written permission of the executive director of the Earthquake Engi- neering Research Institute or the Director of the Bancroft Library of the University of California at Berkeley. Requests for permission to quote for publication should include identification of the specific passages to be quoted, anticipated use of the passages, and identification of the user. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the oral history subject and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or policies of the Earthquake Engineering Research Institute or the University of California. Published by the Earthquake Engineering Research Institute 499 14th Street, Suite 320 Oakland, CA 94612-1934 Tel: (510) 451-0905 Fax: (510) 451-5411 E-Mail: [email protected] Web site: http://www.eeri.org EERI Publication No.: OHS-6 ISBN 0-943198-99-2 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Wallace, R. E. (Robert Earl), 1916- Robert E. Wallace / Stanley Scott, interviewer. p. cm – (Connections: the EERI oral history series ; 7) (EERI publication ; no. -

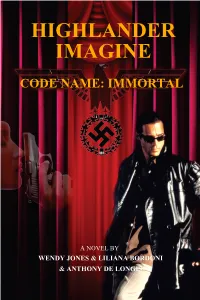

Code Name: Immortal

HIGHLANDER IMAGINE CODE NAME: IMMORTAL A NOVEL BY WENDY JONES & LILIANA BORDONI & ANTHONY DE LONGIS FICTION: ACTION & ADVENTURE/ROMANCE/HISTORICAL "This train can't take a Quickening, it will be destroyed! How many people will die because of us?" IT'S SPY VS SPY with Duncan MacLeod of the Clan MacLeod caught in the middle. When Connor suddenly disappears, Annelise’s desperate plea for Duncan to help her find him pulls the Highlander into a deadly game of cat and mouse. Soon, Duncan is face-to-face with the head of the Hunters’ organization and their darkest secrets. Master of the sword, Anthony De Longis weaves a deadly tale of suspense, intrigue and no-holds-barred sword fights between the Mac Leods and those seeking their Quickenings. This work was fully authorized by Davis-Panzer Productions and Studiocanal Films Ltd; however the content is wholly an RK Books original fan creation. “Since when do Immortals need an excuse to kill Watchers?” Annelise snapped. “It was just evening the score for what those people do to you people. I would’ve done the same,” she finished, coldly. Aghast, Duncan did a double take. “Kill Watchers—what are you saying? What score are you talking about?” “I know now who’s responsible for what happened to my brother,” she continued. “Connor promised he would help me free him—he’s on his way there now, but I know it’s a trap. You’ve got to help me, Duncan. Take me to Connor before it is too late for both of them.” Follow Solo Highlander Imagine Code Name: Immortal An RK Books production www.RK-books.com ISBN: 978-0-9777110-6-2 Copyright © January 4, 2018 by Wendy Lou Jones Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data Jones, Wendy Lou Highlander Imagine: Code Name Immortal by Wendy Lou Jones Fiction: Historical │ Mystery Detective / Historical │ Romance / Action & Adventure Library of Congress Control Number: 2017963943 All rights reserved Highlander Imagine Series This work was fully authorized by Davis-Panzer Productions and Studiocanal Films Ltd; however the content is wholly an RK Books original fan creation. -

Protecting the Crown: a Century of Resource Management in Glacier National Park

Protecting the Crown A Century of Resource Management in Glacier National Park Rocky Mountains Cooperative Ecosystem Studies Unit (RM-CESU) RM-CESU Cooperative Agreement H2380040001 (WASO) RM-CESU Task Agreement J1434080053 Theodore Catton, Principal Investigator University of Montana Department of History Missoula, Montana 59812 Diane Krahe, Researcher University of Montana Department of History Missoula, Montana 59812 Deirdre K. Shaw NPS Key Official and Curator Glacier National Park West Glacier, Montana 59936 June 2011 Table of Contents List of Maps and Photographs v Introduction: Protecting the Crown 1 Chapter 1: A Homeland and a Frontier 5 Chapter 2: A Reservoir of Nature 23 Chapter 3: A Complete Sanctuary 57 Chapter 4: A Vignette of Primitive America 103 Chapter 5: A Sustainable Ecosystem 179 Conclusion: Preserving Different Natures 245 Bibliography 249 Index 261 List of Maps and Photographs MAPS Glacier National Park 22 Threats to Glacier National Park 168 PHOTOGRAPHS Cover - hikers going to Grinnell Glacier, 1930s, HPC 001581 Introduction – Three buses on Going-to-the-Sun Road, 1937, GNPA 11829 1 1.1 Two Cultural Legacies – McDonald family, GNPA 64 5 1.2 Indian Use and Occupancy – unidentified couple by lake, GNPA 24 7 1.3 Scientific Exploration – George B. Grinnell, Web 12 1.4 New Forms of Resource Use – group with stringer of fish, GNPA 551 14 2.1 A Foundation in Law – ranger at check station, GNPA 2874 23 2.2 An Emphasis on Law Enforcement – two park employees on hotel porch, 1915 HPC 001037 25 2.3 Stocking the Park – men with dead mountain lions, GNPA 9199 31 2.4 Balancing Preservation and Use – road-building contractors, 1924, GNPA 304 40 2.5 Forest Protection – Half Moon Fire, 1929, GNPA 11818 45 2.6 Properties on Lake McDonald – cabin in Apgar, Web 54 3.1 A Background of Construction – gas shovel, GTSR, 1937, GNPA 11647 57 3.2 Wildlife Studies in the 1930s – George M. -

Bailey Willis

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES BAILEY WILLIS 1857—1949 A Biographical Memoir by E L I O T B L A C KWELDER Any opinions expressed in this memoir are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Academy of Sciences. Biographical Memoir COPYRIGHT 1961 NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES WASHINGTON D.C. BAILEY WILLIS May 3/, i8^j-February 19,1949 BY ELIOT BLACKWELDER HILE it is not easy to classify as versatile a man as Bailey W Willis, the word explorer fits him best. Although he came too late for the early period of geologic exploration of the western states, he was associated with many of those who had taken part in it, and he grew up with its later stage. The son of a noted poet, it is not strange that he displayed much of the temperament of an artist and that his scientific work should have leaned toward the imaginative and speculative side rather than the rigorously factual. Willis was born on a country estate at Idlewild-on-Hudson in New York, on May 31, 1857. His father, Nathaniel Parker Willis, whose Puritan ancestors settled in Boston in 1630, was well known as a journalist, poet and writer of essays and commentaries; but he died when Bailey was only ten years old. His mother, Cornelia Grinnell Willis, of Quaker ancestry, seems to have been his principal mentor in his youth, inspiring his interest in travel, adventure and explora- tion. At the age of thirteen he was taken to England and Germany for four years of schooling.