Supplemental Text Chapter on the Simple Computer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Design of 8-Bit Arithmetic Processor Unit Based on Reversible Logic by A

Global Journal of Researches in Engineering Electrical and Electronics Engineering Volume 13 Issue 10 Version 1.0 Year 2013 Type: Double Blind Peer Reviewed International Research Journal Publisher: Global Journals Inc. (USA) Online ISSN: 2249-4596 & Print ISSN: 0975-5861 Design of 8-Bit Arithmetic Processor Unit based on Reversible Logic By A. Kamaraj, C. Kalyana Sundaram & J. Senthil Kumar Mepco Schlenk Engineering College, India Abstract - Reversible logic is emerging as an important research area in the recent years due to its ability to reduce the power dissipation, which is the main requirement in low power digital design. Energy dissipation is proportional to the number of bits lost during computation. The reversible circuits do not lose information and can generate unique outputs from specified inputs and vice versa. It has application in diverse fields such as low power CMOS design, optical information processing, cryptography, quantum computation and nanotechnology. This paper proposes a reversible design of an 8 -bit arithmetic processor. The architecture of the processor has been proposed, in which, each block is realized using reversible logic gates. The important blocks of the processor are control unit, arithmetic and logical unit and register file. Each module has been coded using Verilog then simulated using Modelsim and prototyped in Xilinx- Spartan 3E. Keywords : reversible logic, reversible gate, FPGA, xilinx. GJRE-F Classification : FOR Code: 290901 Design of 8-Bit ArithmeticProcessor Unit based on ReversibleLogic Strictly as per the compliance and regulations of : © 2013. A. Kamaraj, C. Kalyana Sundaram & J. Senthil Kumar. This is a research/review paper, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 Unported License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/), permitting all non commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. -

Computer Architecture (BCA Part-I)

Biyani's Think Tank Concept based notes Computer Architecture (BCA Part-I) Micky Haldya Revised By: Jyoti Sharma Deptt. of Information Technology Biyani Girls College, Jaipur 2 Published by : Think Tanks Biyani Group of Colleges Concept & Copyright : Biyani Shikshan Samiti Sector-3, Vidhyadhar Nagar, Jaipur-302 023 (Rajasthan) Ph : 0141-2338371, 2338591-95 Fax : 0141-2338007 E-mail : [email protected] Website :www.gurukpo.com; www.biyanicolleges.org ISBN: 978-93-81254-38-0 Edition : 2011 Price : While every effort is taken to avoid errors or omissions in this Publication, any mistake or omission that may have crept in is not intentional. It may be taken note of that neither the publisher nor the author will be responsible for any damage or loss of any kind arising to anyone in any manner on account of such errors and omissions. Leaser Type Setted by : Biyani College Printing Department For More Details: - www.gurukpo.com Computer Architecture 3 Preface am glad to present this book, especially designed to serve the needs of the I students. The book has been written keeping in mind the general weakness in understanding the fundamental concepts of the topics. The book is self-explanatory and adopts the “Teach Yourself” style. It is based on question-answer pattern. The language of book is quite easy and understandable based on scientific approach. Any further improvement in the contents of the book by making corrections, omission and inclusion is keen to be achieved based on suggestions from the readers for which the author shall be obliged. I acknowledge special thanks to Mr. -

Address Decoding Large-Size Binary Decoder: 28-To-268435456 Binary Decoder for 256Mb Memory

Embedded System 2010 SpringSemester Seoul NationalUniversity Application [email protected] Dept. ofEECS/CSE ower Naehyuck Chang P 4190.303C ow- L Introduction to microprocessor interface mbedded aboratory E L L 1 P L E Harvard Architecture Microprocessor Instruction memory Input: address from PC ARM Cortex M3 architecture Output: instruction (read only) Data memory Input: memory address Addressing mode Input/output: read/write data Read or write operand Embedded Low-Power 2 ELPL Laboratory Memory Interface Interface Address bus Data bus Control signals (synchronous and asynchronous) Fully static read operation Input Memory Output Access control Embedded Low-Power 3 ELPL Laboratory Memory Interface Memory device Collection of memory cells: 1M cells, 1G cells, etc. Memory cells preserve stored data Volatile and non-volatile Dynamic and static How access memory? Addressing Input Normally address of the cell (cf. content addressable memory) Memory Random, sequential, page, etc. Output Exclusive cell access One by one (cf. multi-port memory) Operations Read, write, refresh, etc. RD, WR, CS, OE, etc. Access control Embedded Low-Power 4 ELPL Laboratory Memory inside SRAM structure Embedded Low-Power 5 ELPL Laboratory Memory inside Ports Recall D-FF 1 input port and one output port for one cell Ports of memory devices Large number of cells One write port for consistency More than one output ports allow simultaneous accesses of multiple cells for read Register file usually has multiple read ports such as 1W 3R Memory devices usually has one read -

Modeling and Implementation of a 6-Bit, 50Mhz Pipelined ADC in CMOS

Qazi Omar Farooq Omar Qazi Modeling and Implementation of A 6- Bit, 50MHz Pipelined ADC in CMOS Master’s Thesis Modeling and Implementation of A 6-Bit, 50MHz Pipelined ADC in CMOS Qazi Omar Farooq Series of Master’s theses Department of Electrical and Information Technology LU/LTH-EIT 2016-549 http://www.eit.lth.se Department of Electrical and Information Technology, Faculty of Engineering, LTH, Lund University, 2016. Master’s Thesis Modeling and Implementation of A 6- Bit, 50MHz Pipelined ADC in CMOS By QAZI OMAR FAROOQ Department of Electrical and Information Technology Faculty of Engineering, LTH, Lund University SE-221 00 Lund, Sweden Abstract The pipelined ADC is a popular Nyquist-rate data converter due to its attractive feature of maintaining high accuracy at high conversion rate with low complexity and power consumption. The rapid growth of its application such as mobile system, digital video and high speed data acquisition is driving the pipelined ADC design towards higher speed, higher precision with lower supply voltage and power consumption. This thesis project aims at modeling and implementation of a pipelined ADC with high speed and low power consumption. 2 Acknowledgements First of all, I would like to thank Almighty ALLAH for giving me the strength to complete this work. My supervisor Mr. Xiaodong Liu needs a big appreciation here because he helped me at every stage of my work. Whenever I found myself stuck in a problem he helped me and gave me some very useful suggestion which proved very helpful to me. Without his constant support and guidance this work wouldn’t be completed. -

Unit-4 Combinational Logic Design

UNIT-4 COMBINATIONAL LOGIC DESIGN DECODERS: A decoder is a multiple-input, multiple-output logic circuit that converts coded inputs into coded outputs, where the input and output codes are different. The input code generally has fewer bits than the output code, and there is a one-to one mapping from input code words into output code words. In a one-to-one mapping, each input code word produces a different output code word. The general structure of a decoder circuit is shown in Figure 1. The enable inputs, if present, must be asserted for the decoder to perform its normal mapping function. Otherwise, the decoder maps all input code words into a single, ―disabled,‖ output code word. The most commonly used output code is a 1-out-of-m code, which contains m bits, where one bit is asserted at any time. Thus, in a 1-out-of-4 code with active-high outputs, the code words are 0001, 0010, 0100, and 1000. With active-low outputs, the code words are 1110, 1101, 1011, and 0111. BINARY DECODERS The most common decoder circuit is an n-to-2n decoder or binary decoder. Such a decoder has an n-bit binary input code and a 1-out-of-2n output code. A binary decoder is used when you need to activate exactly one of 2n outputs based on an n- bit input value. Table 1 is the truth table of a 2-to-4 decoder. The input code word I1,I0 represents an integer in the range 0–3. The output code word Y3,Y2,Y1,Y0 has Yi equal to 1 if and only if the input code word is the binary representation of i and the enable input EN is 1. -

Regular Low-Density Parity-Check Code Decoder

EURASIP Journal on Applied Signal Processing 2003:6, 530–542 c 2003 Hindawi Publishing Corporation An FPGA Implementation of (3, 6)-Regular Low-Density Parity-Check Code Decoder Tong Zhang Department of Electrical, Computer, and Systems Engineering, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Troy, NY 12180, USA Email: [email protected] Keshab K. Parhi Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA Email: [email protected] Received 28 February 2002 and in revised form 6 December 2002 Because of their excellent error-correcting performance, low-density parity-check (LDPC) codes have recently attracted a lot of attention. In this paper, we are interested in the practical LDPC code decoder hardware implementations. The direct fully parallel decoder implementation usually incurs too high hardware complexity for many real applications, thus partly parallel decoder design approaches that can achieve appropriate trade-offs between hardware complexity and decoding throughput are highly desirable. Applying a joint code and decoder design methodology, we develop a high-speed (3,k)-regular LDPC code partly parallel decoder architecture based on which we implement a 9216-bit, rate-1/2(3, 6)-regular LDPC code decoder on Xilinx FPGA device. This partly parallel decoder supports a maximum symbol throughput of 54 Mbps and achieves BER 10−6 at 2 dB over AWGN channel while performing maximum 18 decoding iterations. Keywords and phrases: low-density parity-check codes, error-correcting coding, decoder, FPGA. 1. INTRODUCTION decoding messages are iteratively computed on each variable In the past few years, the recently rediscovered low-density node and check node and exchanged through the edges be- parity-check (LDPC) codes [1, 2, 3] have received a lot of at- tween the neighboring nodes. -

School of Electrical & Computer Engineering Purdue University

School of Electrical & Computer Engineering ECE 270 Lecture Module 2 Purdue University, College of Engineering Spring 2019 Edition Purdue IM:PACT* Spring 2019 Edition *Instruction Matters: Purdue Academic Glossary of Common Terms Course Transformation DISCRETE LOGIC – a circuit constructed using small-scale integrated (SSI) and medium-scale integrated (MSI) logic devices (NAND gates, decoders, Introduction to Digital System Design multiplexers, etc.) PROGRAMMABLE LOGIC DEVICE (PLD) – an integrated circuit onto which a generic logic circuit can be programmed (and subsequently erased and re-programmed) GENERIC ARRAY LOGIC (GAL) –a (legacy) flash memory based PLD, which is typically erased and re-programmed out- Module 2 of-circuit Combinational Logic Circuits COMPLEX PLD (CPLD) – large flash memory based PLD that is programmable in-circuit 2 Glossary of Common Terms Module 2 isp (IN-SYSTEM PROGRAMMING) –prefix Learning Outcome: “An ability to analyze and design used on CPLDs that can be erased and re- combinational logic circuits” programmed in-circuit A. Combinational Circuit Analysis and Synthesis FIELD PROGRAMMABLE GATE ARRAY B. Mapping and Minimization (FPGA) – an SRAM-based PLD that can be C. Timing Hazards programmed in-circuit (no need to “erase” D. XOR/XNOR Functions since SRAM-based) E. Programmable Logic Devices ADVANCED BOOLEAN EXPRESSION F. Hardware Description Languages LANGUAGE (ABEL) – a “classic” hardware G. Combinational Building Blocks: Decoders description language (HDL) for specifying the behavior of PLDs H. Combinational Building Blocks: Encoders and Tri-State Outputs I. Combinational Building Blocks: Multiplexers VHDL and VERILOG – advanced hardware J. Top Level Modules simulation and description languages 3 4 Purdue IM:PACT* Spring 2019 Edition Reading Assignment: *Instruction Matters: Purdue Academic th th Course Transformation DDPP 4 Ed. -

Certification of an Instruction Set Simulator Xiaomu Shi

Certification of an Instruction Set Simulator Xiaomu Shi To cite this version: Xiaomu Shi. Certification of an Instruction Set Simulator. Embedded Systems. Université de Greno- ble, 2013. English. NNT : 2013GRENM075. tel-00937524v2 HAL Id: tel-00937524 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-00937524v2 Submitted on 28 Jun 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. THÈSE Pour obtenir le grade de DOCTEUR DE L’UNIVERSITÉ DE GRENOBLE Spécialité : Informatique Arrêté ministérial : 7 août 2006 Présentée par Xiaomu SHI Thèse dirigée par Jean-François MONIN et codirigée par Vania JOLOBOFF préparée au sein de VERIMAG et de Mathématiques, Sciences et Technologies de l’Information, Informatique Certification of an Instruction Set Simulator Thèse soutenue publiquement le 10 juillet 2013, devant le jury composé de : M. Yves Bertot Directeur de Recherche, INRIA Sophia-Antipolis, Examinateur Mme Sandrine Blazy Professeur, IRISA, Rapporteur M. Vania Joloboff Directeur de Recherche, LIAMA, Co-Directeur de thèse M. Xavier Leroy Directeur de Recherche, INRIA Rocquencourt, Examinateur M. Laurent Maillet-Contoz Ingénieur, STMicroelectronics, Examinateur M. Claude Marché Directeur de Recherche, INRIA Saclay - Île-de-France et LRI, Rapporteur M. Jean-François Monin Professeur, Université de Grenoble 1 UJF, Directeur de thèse M. -

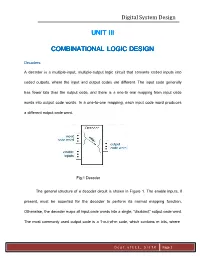

Unit Iii Combinational Logic Design

Digital System Design UNIT III COMBINATIONAL LOGIC DESIGN Decoders: A decoder is a multiple-input, multiple-output logic circuit that converts coded inputs into coded outputs, where the input and output codes are different. The input code generally has fewer bits than the output code, and there is a one-to one mapping from input code words into output code words. In a one-to-one mapping, each input code word produces a different output code word. Fig:1 Decoder The general structure of a decoder circuit is shown in Figure 1. The enable inputs, if present, must be asserted for the decoder to perform its normal mapping function. Otherwise, the decoder maps all input code words into a single, “disabled,” output code word. The most commonly used output code is a 1-out-of-m code, which contains m bits, where D e p t . o f E C E , S I E T K Page 1 Digital System Design one bit is asserted at any time. Thus, in a 1-out-of-4 code with active-high outputs, the code words are 0001, 0010, 0100, and 1000. With active-low outputs, the code words are 1110, 1101, 1011, and 0111. Binary Decoders The most common decoder circuit is an n-to-2n decoder or binary decoder. Such a decoder has an n-bit binary input code and a 1-out-of-2n output code. A binary decoder is used when you need to activate exactly one of 2n outputs based on an n-bit input value Table 1 is the truth table of a 2-to-4 decoder. -

Ece421) Digital Electronics Fundamental (Ece422

DIGITAL SYSTEM FUNDAMENTALS (ECE421) COURSE / CODE DIGITAL ELECTRONICS FUNDAMENTAL (ECE422) Medium Scale Integrated (MSI) devices It’s sometimes not reasonable to do all the design work at the gate-level. For example, it is a common practice to use full-adders as the building blocks in building a ripple-carry adder. When designing circuits, there are certain building blocks that are used over and over again. Thus, being familiar with a set of building blocks that are commonly used can make designing digital devices easier. Building blocks that are more complex than gates are sometimes called medium-scale integrated devices, or MSI devices for short. Exactly what makes a device “medium” in scale rather than “large” or “very large” (as in VLSI) is not always agreed on, but generally it’s all right stick with devices that are fairly simple and where small versions of them can be implemented in a couple dozen gates or so. Special Combinational Logic Circuits 1. Adders A half adder can add two bits. It has two inputs, generally labeled A and B, and two outputs, the sum S and carry C. S is the two-bit XOR of A and B, and C is the AND of A and B. Essentially the output of a half adder is the sum of two one-bit numbers, with C being the most significant of these two outputs. A half adder is a logical circuit that performs an addition operation on two binary digits. The half adder produces a sum and a carry value which are both binary digits. -

Multivalued Circuits and Interconnect Issues

Multivalued circuits and Interconnect issues Daniel Etiemble Computer Science Laboratory (LRI) Paris Saclay University Orsay, France [email protected] Abstract—Many papers have presented multi-valued circuits in various technologies as a solution to reduce or solve intercon- nection issues in binary circuits. This assumption is discussed. While 4-valued signaling could divide by two the number of interconnects between building blocks, it turns out that circuit designers use interconnect standards based on differential pairs such as PCIe, Infiniband, RapidIO, NVLink, etc. Doubling the Fig. 2. 4-valued circuits in a binary environment number of binary signals is a better solution than using single- ended quaternary signals. The design of quaternary basic gates, adders and multipliers are compared with the corresponding II. METHODOLOGY binary ones. At each level, the transistor count ratio between quaternary and binary circuits is greater than the x2 information In the last decade, most proposed designs of m-valued ratio between base 4 and base 2. Quaternary signaling is not a circuits use simulations of CNTFET technologies. The CNT- solution, either between or within circuit blocks . FET circuitry is similar to the CMOS one while presenting a significant advantage: the threshold voltage varies as the in- I. INTRODUCTION verse function of the diameter of the tube. Different diameters Many published papers proposing new m-valued circuits provide the different threshold voltages that are needed in m- justified their proposal by interconnection issues in binary valued circuits. circuits. Just to present one among a lot of quotes, "One However, this technology is far from being mature. In 2019, of the main problems in binary logic is the high volume of a 16-bit RISC microprocessor has been built with 14,000 interconnections which can increase the chip area and power CNFET transistors [2]. -

Lecture Summary Notes

ECE 270 IM:PACT Introduction to Digital System Design © 2019 by D. G. Meyer Lecture Summary – Module 2 Combinational Logic Circuits Learning Outcome: an ability to analyze and design combinational logic circuits Learning Objectives: 2-1. identify minterms (product terms) and maxterms (sum terms) 2-2. list the standard forms for expressing a logic function and give an example of each: sum-of-products (SoP), product-of-sums (PoS), ON set, OFF set 2-3. analyze the functional behavior of a logic circuit by constructing a truth table that lists the relationship between input variable combinations and the output variable 2-4. transform a logic circuit from one set of symbols to another through graphical application of DeMorgan’s Law 2-5. realize a combinational function directly using basic gates (NOT, AND, OR, NAND, NOR) 2-6. draw a Karnaugh Map (“K-map”) for a 2-, 3-, 4-, or 5-variable logic function 2-7. list the assumptions underlying function minimization 2-8. identify the prime implicants, essential prime implicants, and non-essential prime implicants of a function depicted on a K-map 2-9. use a K-map to minimize a logic function (including those that are incompletely specified) and express it in either minimal SoP or PoS form 2-10. use a K-map to convert a function from one standard form to another 2-11. calculate and compare the cost (based on the total number of gate inputs plus the number of gate outputs) of minimal SoP and PoS realizations of a given function 2-12. realize a function depicted on a K-map as a two-level NAND circuit, two-level NOR circuit, or as an open- drain NAND/wired-AND circuit 2-13.