The Frontiersman from Lout to Hero Notes on the Significance Ofthe Comparative Method and the Stage Theory in Early American Literature and Cidture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Influence of the Irish Tudor and Stuart Plantation Experiences in the Evolution of American Colonial Theory and Practice

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1992 "This Famous Island in the Virginia Sea": The Influence of the Irish Tudor and Stuart Plantation Experiences in the Evolution of American Colonial Theory and Practice Meaghan Noelle Duff College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Duff, Meaghan Noelle, ""This Famous Island in the Virginia Sea": The Influence of the Irish udorT and Stuart Plantation Experiences in the Evolution of American Colonial Theory and Practice" (1992). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625771. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-kvrp-3b47 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "THIS FAMOUS ISLAND IN THE VIRGINIA SEA": THE INFLUENCE OF IRISH TUDOR AND STUART PLANTATION EXPERIENCES ON THE EVOLUTION OF AMERICAN COLONIAL THEORY AND PRACTICE A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY THE COLLEGE OF WILLIAM AND MARY IN VIRGINIA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS BY MEAGHAN N. DUFF MAY, 1992 APPROVAL SHEET THIS THESIS IS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS AGHAN N APPROVED, MAY 1992 '''7 ^ ^ THADDEUS W. TATE A m iJI________ JAMES AXTELL CHANDOS M. -

Early Colonial Life

Early Colonial Life The 16th century was the age of mercantilism, an extremely competitive economic philosophy that pushed European nations to acquire as many colonies as they could. As a result, for the most part, the English colonies in North America were business ventures. They provided an outlet for England’s surplus population and more religious freedom than England did, but their primary purpose was to make money for their sponsors. The first English settlement in North America was established in 1587, when a group of colonists (91 men, 17 women and nine children) led by Sir Walter Raleigh settled on the island of Roanoke. Mysteriously, the Roanoke colony had vanished entirely. Historians still do not know what became of its inhabitants. In 1606, King James I divided the Atlantic seaboard in two, giving the southern half to the Virginia Company and the northern half to the Plymouth Company. In 1606, just a few months after James I issued its charter, the London Company sent 144 men to Virginia on three ships: the Godspeed, the Discovery and the Susan Constant. They reached the Chesapeake Bay in the spring of 1607 and headed about 60 miles up the James River, where they built a settlement they called Jamestown. The Jamestown colonists had a rough time of it: They were so busy looking for gold and other exportable resources that they could barely feed themselves. It was not until 1616, when Virginia’s settlers learned to grow tobacco and John Smith’s leadership helped the colony survive. The first African slaves arrived in Virginia in 1619. -

Hclassification

Form No. 10-306 (Rev. 10-74) J, UN1TEDSTATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR FEDERAL PROPERTIES SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ____________TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS___________ | NAME HISTORIC Lane's New Fort in Virginia/Cittie of Raleigh AND/OR COMMON ~ Fort Raleigh National Historic Site ( \\ ^f I____________ LOCATION STREETS.NUMBER North end of Roanoke Island; 1 mile east of William B. Umstead Memorial Bridge on U.S. 64. —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Manteo — VICINITY OF First STATE CODE COUNTY CODE North Carolina 37 Dare 055 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT ^.PUBLIC X-OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED _ COMMERCIAL 2L.PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS -^.EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE XsiTE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE JCENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _ IN PROCESS —YES. RESTRICTED X.GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED X_YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: [AGENCY REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS: (If applicable) National Park Service. Department of the Interior, Southeast Regional Office STREET 8» NUMBER 1895 Phoenix Boulevard CITY. TOWN STATE Atlanta VICINITY OF Georgia 30349 LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC. Dare County Courthouse/Register of Deeds STREET & NUMBER Courthouse Building CITY, TOWN STATE Manteo North Carolina 27954 TITLE DATE —FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL CITY. TOWN STATE DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —XEXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X.ORIGINALSITE —GOOD —RUINS JCALTERED —MOVED DATE- —FAIR —UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The boundaries of Fort Raleigh National Historic Site include 159 acres. However, most of this acreage is either developed area, being managed as a natural area or the Elizabethan Gardens maintained by the Garden Club of North Carolina. -

The Planting of English America ᇻᇾᇻ 1500–1733

2 The Planting of English America ᇻᇾᇻ 1500–1733 . For I shall yet to see it [Virginia] an Inglishe nation. SIR WALTER RALEIGH, 1602 s the seventeenth century dawned, scarcely a three European powers planted three primitive out- Ahundred years after Columbus’s momentous posts in three distant corners of the continent landfall, the face of m uch of the New World had within three years of one another: the Spanish at already been profoundly transformed. European Santa Fe in 1610, the French at Quebec in 1608, and, crops and livestock had begun to alter the very land- most consequentially for the future United States, scape, touching off an ecological revolution that the English at Jamestown, Virginia, in 1607. would reverberate for centuries to come. From Tierra del Fuego in the south to Hudson Bay in the north, disease and armed conquest had cruelly win- England’s Imperial Stirrings nowed and disrupted the native peoples. Several hundred thousand enslaved Africans toiled on Caribbean and Brazilian sugar plantations. From Feeble indeed were England’s efforts in the 1500s to Florida and New Mexico southward, most of the New compete with the sprawling Spanish Empire. As World lay firmly within the grip of imperial Spain. Spain’s ally in the first half of the century, England Bu t North America in 1600 remained largely took little interest in establishing its own overseas unexplored and effectively unclaimed by Euro- colonies. Religious conflict, moreover, disrupted peans. Then, as if to herald the coming century of England in midcentury, after King Henry VIII broke colonization and conflict in the northern continent, with the Roman Catholic Church in the 1530s, 25 26 CHAPTER 2The Planting of English America, 1500–1733 launching the English Protestant Reformation. -

Commonlit | Settling a New World: the Lost Colony of Roanoke Island

Name: Class: Settling a New World: The Lost Colony of Roanoke Island By National Park Service 2016 The Fort Raleigh National Historic Site is dedicated to the preservation of England’s first New World settlements, as well as the cultural legacy of Native Americans, European Americans, and African Americans who lived on Roanoke Island. In 1585 and 1587, England tried its hand at establishing a colonial presence in North America under the leadership of Sir Walter Raleigh. The attempts were failures on both accounts but they would come to form one of the most puzzling mysteries in early American history: the disappearance of the Roanoke colony. As you read, take notes on what circumstances or mistakes might have put the English settlers at a disadvantage in creating a lasting colony. [1] "About the place many of my things spoiled and broken, and my books torn from the covers, the frames of some of my pictures and maps rotted and spoiled with rain, and my armor almost eaten through with rust." - John White1 on the lost colony of Roanoke Island 1584 Voyage In the late sixteenth-century, England’s primary goal in North America was to disrupt Spanish "John White discovers the word "CROATOAN" carved at Roanoke's shipping. Catholic Spain, under the rule of Philip fort palisade" by Unknown is in the public domain. II,2 had dominated the coast of Central and South America, the Caribbean, and Florida for the latter part of the 1500s. Protestant England, under the rule of Elizabeth I,3 sought to circumvent4 Spanish dominance in the region by establishing colonies in the New World. -

Introduction English Worthies: the Age of Expansion Remembered 1

Notes Introduction English Worthies: The Age of Expansion Remembered 1. Fuller, History of the Worthies of England (London, 1662), 318/Sss2v (pagination to both editions is unreliable; I have given page numbers where these seem useful, followed by signature). Subsequent citations to the two editions of Fuller’s work are given in the text as Worthies 1684 or Worthies 1662. 2. For copies of Hariot, I have consulted the online English Short Title Catalogue (ESTC) at http://estc.bl.uk (accessed July 2007). 3. I am indebted for these references to Matthew Day’s excellent thesis on Hakluyt, Richard Hakluyt’s Principal Navigations (1598–1600) and the Textuality of Tudor English Nationalism. (D. Phil., York, 2003). 4. Hakluyt’s 1589 collection included a brief account of the circumnavi- gation summarized from a manuscript no longer extant—these “Drake leaves,” 12 folio sides of black letter text, fall between pages 643 and 644 but are themselves unpaginated, an indication that they were added at some point after the rest of the volume had gone to press. The first full-length account of Drake’s epochal voyage in English, The World Encompassed, did not appear until 1628, several decades after Drake’s death. 5. Cal. S.P. For. 1584–85, 19:108. Harry Kelsey thinks the reference is to the circumnavigation of 1577–80 (Sir Francis Drake: The Queen’s Pirate [New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998], 178). Mary Frear Keeler believes the reference is to evolving plans for what became Drake’s voyage to the West Indies in 1585–86 (Sir Francis Drake’s West Indian Voyage. -

"Theater and Empire: a History of Assumptions in the English-Speaking Atlantic World, 1700-1860"

"THEATER AND EMPIRE: A HISTORY OF ASSUMPTIONS IN THE ENGLISH-SPEAKING ATLANTIC WORLD, 1700-1860" BY ©2008 Douglas S. Harvey Submitted to the graduate degree program in History and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ____________________________________ Chairperson Committee Members* ___________________________________* ___________________________________* ___________________________________* ___________________________________* Date Defended: April 7, 2008 The Dissertation Committee for Douglas S. Harvey certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: "THEATER AND EMPIRE: A HISTORY OF ASSUMPTIONS IN THE ENGLISH-SPEAKING ATLANTIC WORLD, 1700-1860" Committee ____________________________________ Chairperson ___________________________________* ___________________________________* ___________________________________* ___________________________________* Date Approved: April 7, 2008 ii Abstract It was no coincidence that commercial theater, a market society, the British middle class, and the “first” British Empire arose more or less simultaneously. In the seventeenth century, the new market economic paradigm became increasingly dominant, replacing the old feudal economy. Theater functioned to “explain” this arrangement to the general populace and gradually it became part of what I call a “culture of empire” – a culture built up around the search for resources and markets that characterized imperial expansion. It also rationalized the depredations the Empire brought to those whose resources and labor were coveted by expansionists. This process intensified with the independence of the thirteen North American colonies, and theater began representing Native Americans and African American populations in ways that rationalized the dominant society’s behavior toward them. By utilizing an interdisciplinary approach, this research attempts to advance a more nuanced and realistic narrative of empire in the early modern and early republic periods. -

Mapmaking in England, Ca. 1470–1650

54 • Mapmaking in England, ca. 1470 –1650 Peter Barber The English Heritage to vey, eds., Local Maps and Plans from Medieval England (Oxford: 1525 Clarendon Press, 1986); Mapmaker’s Art for Edward Lyman, The Map- world maps maker’s Art: Essays on the History of Maps (London: Batchworth Press, 1953); Monarchs, Ministers, and Maps for David Buisseret, ed., Mon- archs, Ministers, and Maps: The Emergence of Cartography as a Tool There is little evidence of a significant cartographic pres- of Government in Early Modern Europe (Chicago: University of Chi- ence in late fifteenth-century England in terms of most cago Press, 1992); Rural Images for David Buisseret, ed., Rural Images: modern indices, such as an extensive familiarity with and Estate Maps in the Old and New Worlds (Chicago: University of Chi- use of maps on the part of its citizenry, a widespread use cago Press, 1996); Tales from the Map Room for Peter Barber and of maps for administration and in the transaction of busi- Christopher Board, eds., Tales from the Map Room: Fact and Fiction about Maps and Their Makers (London: BBC Books, 1993); and TNA ness, the domestic production of printed maps, and an ac- for The National Archives of the UK, Kew (formerly the Public Record 1 tive market in them. Although the first map to be printed Office). in England, a T-O map illustrating William Caxton’s 1. This notion is challenged in Catherine Delano-Smith and R. J. P. Myrrour of the Worlde of 1481, appeared at a relatively Kain, English Maps: A History (London: British Library, 1999), 28–29, early date, no further map, other than one illustrating a who state that “certainly by the late fourteenth century, or at the latest by the early fifteenth century, the practical use of maps was diffusing 1489 reprint of Caxton’s text, was to be printed for sev- into society at large,” but the scarcity of surviving maps of any descrip- 2 eral decades. -

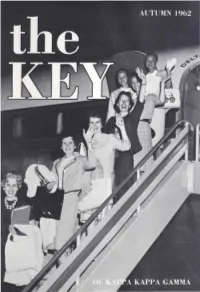

THE KEY VOL 79 NO 3 AUTUMN 1962.Pdf

VOLUME 79 NUMBER 3 The first college women's frat ernity magazine Published continuously the KEY since 1882 OF KAPPA KAPPA GAMMA AUTUMN 1962 Send all editorial material and COVER: Airborne Kappas arrive on the first charter flight to correspondence to the a Kappa convention. Ranging up the steps, they are: Barbara EDITOR Russell Kunz, n A-Illinois, Champaign-Urbana alumna dele Mrs. Robert H . Simmons gate; Sue Sather, n IT-Washington, active delegate; ~ancy 15 6 North Roosevelt Avenue Columbus 9, Ohio Sampson Nethercutt, r H-Washington State, alumna VISitor; Virginia Pitts Malico, r r-Whitman, Spokane alumna deleg_ate; Martha Lynn, X-Minnesota, active visitor; Karen Rushmg, Send all business i terns to the X-Minnesota, active delegate; Diane Haas Clover, n-Kansas, BUSINESS MANAGER adviser to r Z-Arizona. Miss Clara 0. Pierce Fraternity Headquarters 530 East Town Street 3 Devotional given at opening session Columbus 16, Ohio (For other devotionals, see pages 11, 27, 29, 43, and 45) Send changes of address, six weeks prior to month of pub .. 4 " ... four square to all the winds that blow" lication, to 9 What I wish for a fraternity chapter FRATERNITY HEADQUARTERS 12 The rest is our own doing 530 East Town Street 19 The state of the Kappa union Columbus 16, Ohio 22 "All mimsy were the Borogoves" (Duplicate copies cannot be sent to replace those unde 23 Scholarship grants announced livered through failure to send advance notice.) 28 The World and K K r 30 A bit of this and that Deadline dates are August 1, September 25, November 15, 32 Alumnre Day activity January 15 for Autumn, Winter, Mid-Winter, and 33 Magazine sales bring rewards Spring issues respectively. -

13 Things You Didn't Know About the 13 Colonies by Liana Mahoney

Name : 13 Things You Didn't Know About the 13 Colonies by Liana Mahoney You probably already know the story of Maine (part of America's thirteen colonies. It's a story of perseverance, Massachusetts) New Hampshire danger, adventure, and luck. It is the story of Virginia, Massachusetts New York Rhode Island Connecticut Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New York, Maryland, Pennsylvania New Jersey Delaware Rhode Island, Connecticut, Delaware, North Carolina, Maryland Virginia New Jersey, South Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Georgia. North Carolina South Carolina At !rst, these colonies followed the rules and laws of Georgia Atlantic Ocean England, but it wasn't long before they decided they wanted to govern themselves. As a result, in 1776, it became the story of the birth of a nation, when these original thirteen colonies fought for their independence and became the United States of America. What else is there to know? Here are thirteen lesser-known facts that you may not have known about the thirteen colonies. 1. There was a lost colony. In 1585, Sir Walter Raleigh began the !rst English settlement in North America on Roanoke Island, just o" the coast of what we now know as North Carolina. Living conditions here were so harsh that the colonists had no choice but to return to England just a year later. In 1587, Raleigh sent a second group of colonists, led by a man named John White. White left his family temporarily to sail back to England for more supplies. When he returned two years later, the colony had vanished! Everyone was gone. Carved into the bark of a tree was a single word: Croatoan. -

The Planting of English America ᇻᇾᇻ 1500–1733

2 The Planting of English America ᇻᇾᇻ 1500–1733 . For I shall yet to see it [Virginia] an Inglishe nation. SIR WALTER RALEIGH, 1602 s the seventeenth century dawned, scarcely a three European powers planted three primitive out- A hundred years after Columbus’s momentous posts in three distant corners of the continent landfall, the face of much of the New World had within three years of one another: the Spanish at already been profoundly transformed. European Santa Fe in 1610, the French at Quebec in 1608, and, crops and livestock had begun to alter the very land- most consequentially for the future United States, scape, touching off an ecological revolution that the English at Jamestown, Virginia, in 1607. would reverberate for centuries to come. From Tierra del Fuego in the south to Hudson Bay in the north, disease and armed conquest had cruelly win- England’s Imperial Stirrings nowed and disrupted the native peoples. Several hundred thousand enslaved Africans toiled on Caribbean and Brazilian sugar plantations. From Feeble indeed were England’s efforts in the 1500s to Florida and New Mexico southward, most of the New compete with the sprawling Spanish Empire. As World lay firmly within the grip of imperial Spain. Spain’s ally in the first half of the century, England But North America in 1600 remained largely took little interest in establishing its own overseas unexplored and effectively unclaimed by Euro- colonies. Religious conflict, moreover, disrupted peans. Then, as if to herald the coming century of England in midcentury, after King Henry VIII broke colonization and conflict in the northern continent, with the Roman Catholic Church in the 1530s, 25 26 CHAPTER 2 The Planting of English America, 1500–1733 launching the English Protestant Reformation. -

Birth of a Colony North Carolina Guide for Educators Act III—The Roanoke

Birth of a Colony North Carolina Guide for Educators Act III—The Roanoke Voyages, 1584–1590 Birth of a Colony Guide for Educators Birth of a Colony explores the history of North Carolina from the time of European exploration through the Tuscarora War. Presented in five acts, the video combines primary sources and expert commentary to bring this period of our history to life. Use this study guide to enhance students’ understanding of the ideas and information presented in the video. The guide is organized according to the video’s five acts. Included for each act are a synopsis, a vocabulary list, discussion questions, and lesson plans. Going over the vocabulary with students before watching the video will help them better understand the film’s content. Discussion questions will encourage students to think critically about what they have viewed. Lesson plans extend the subject matter, providing more information or opportunity for reflection. The lesson plans follow the new Standard Course of Study framework that takes effect with the 2012–2013 school year. With some adjustments, most of the questions and activities can be adapted for the viewing audience. Birth of a Colony was developed by the North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, in collaboration with UNC-TV and Horizon Productions. More resources are available at the website http://www.unctv.org/birthofacolony/index.php. 2 Act III—The Roanoke Voyages, 1584–1590 Act III of Birth of a Colony presents the story of England’s attempts to settle in the New World. Queen Elizabeth enlisted Sir Walter Raleigh to launch an expedition “to inhabit and possess” any lands not already claimed by Spain or France.