The Early History of India, from 600 B.C. to the Muhammadan Conquest, Including the Invasion of Alexander the Great

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

341 BC the THIRD PHILIPPIC Demosthenes Translated By

1 341 BC THE THIRD PHILIPPIC Demosthenes translated by Thomas Leland, D.D. Notes and Introduction by Thomas Leland, D.D. 2 Demosthenes (383-322 BC) - Athenian statesman and the most famous of Greek orators. He was leader of a patriotic party opposing Philip of Macedon. The Third Philippic (341 BC) - The third in a series of speeches in which Demosthenes attacks Philip of Macedon. Demosthenes urged the Athenians to oppose Philip’s conquests of independent Greek states. Cicero later used the name “Philippic” to label his bitter speeches against Mark Antony; the word has since come to stand for any harsh invective. 3 THE THIRD PHILIPPIC INTRODUCTION To the Third Philippic THE former oration (The Oration on the State of the Chersonesus) has its effect: for, instead of punishing Diopithes, the Athenians supplied him with money, in order to put him in a condition of continuing his expeditions. In the mean time Philip pursued his Thracian conquests, and made himself master of several places, which, though of little importance in themselves, yet opened him a way to the cities of the Propontis, and, above all, to Byzantium, which he had always intended to annex to his dominions. He at first tried the way of negotiation, in order to gain the Byzantines into the number of his allies; but this proving ineffectual, he resolved to proceed in another manner. He had a party in the city at whose head was the orator Python, that engaged to deliver him up one of the gates: but while he was on his march towards the city the conspiracy was discovered, which immediately determined him to take another route. -

VU Research Portal

VU Research Portal The impact of empire on market prices in Babylon Pirngruber, R. 2012 document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) Pirngruber, R. (2012). The impact of empire on market prices in Babylon: in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 - 140 B.C. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 25. Sep. 2021 THE IMPACT OF EMPIRE ON MARKET PRICES IN BABYLON in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 – 140 B.C. R. Pirngruber VRIJE UNIVERSITEIT THE IMPACT OF EMPIRE ON MARKET PRICES IN BABYLON in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 – 140 B.C. ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad Doctor aan de Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, op gezag van de rector magnificus prof.dr. -

The Sweep of History

STUDENT’S World History & Geography 1 1 1 Essentials of World History to 1500 Ver. 3.1.10 – Rev. 2/1/2011 WHG1 The following pages describe significant people, places, events, and concepts in the story of humankind. This information forms the core of our study; it will be fleshed-out by classroom discussions, audio-visual mat erials, readings, writings, and other act ivit ies. This knowledge will help you understand how the world works and how humans behave. It will help you understand many of the books, news reports, films, articles, and events you will encounter throughout the rest of your life. The Student’s Friend World History & Geography 1 Essentials of world history to 1500 History What is history? History is the story of human experience. Why study history? History shows us how the world works and how humans behave. History helps us make judgments about current and future events. History affects our lives every day. History is a fascinating story of human treachery and achievement. Geography What is geography? Geography is the study of interaction between humans and the environment. Why study geography? Geography is a major factor affecting human development. Humans are a major factor affecting our natural environment. Geography affects our lives every day. Geography helps us better understand the peoples of the world. CONTENTS: Overview of history Page 1 Some basic concepts Page 2 Unit 1 - Origins of the Earth and Humans Page 3 Unit 2 - Civilization Arises in Mesopotamia & Egypt Page 5 Unit 3 - Civilization Spreads East to India & China Page 9 Unit 4 - Civilization Spreads West to Greece & Rome Page 13 Unit 5 - Early Middle Ages: 500 to 1000 AD Page 17 Unit 6 - Late Middle Ages: 1000 to 1500 AD Page 21 Copyright © 1998-2011 Michael G. -

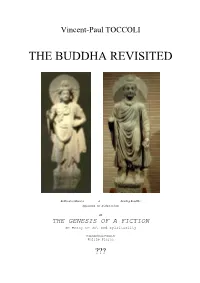

The Buddha Revisited

Vincent-Paul TOCCOLI THE BUDDHA REVISITED Bodhisattva Maitreya & Standing Bouddha Afghanistan, 1er & 2ème sicècles or THE GENESIS OF A FICTION an essay on art and spirituality Translated from French by Philip Pierce ??? "Stories do not belong to eternity "They belong to time "And out of time they grow... "It is in time "That stories, relived and redreamed "Become timeless... "Nations and people are largely the stories they feed themselves "If they tell themselves stories that are lies, "They will suffer the future consequences of those lies. "If they tell themselves stories that free their own truths "They will free their histories forfuture flowerings. (Ben OKRI, Birds of heaven, 25, 15) "Dans leur prétention à la sagesse, "Ils sont devenus fous, "Et ils ont changé la gloire du dieu incorruptible "Contre une représentation, "Simple image d`homme corruptible. (St Paul, to the Romans, 1, 22-23) C O N T E N T S INTRODUCTION FIRST PART: THE MAKING-SENSE TRANSGRESSIONS 1st SECTION: ON THE GANGES SIDE, 5th-1st cent. BC. Chap.1: The Buddhism of the Buddha Chap.2: The state of Buddhism under the last Mauryas 2nd SECTION: ON THE INDUS SIDE, 4th-1st cent. BC. Chap.3: The permanence of Philhellenism, from the Graeco-bactrians to the Scytho-Parthans Chap.4: An approach to the graeco-hellenistic influence SECOND PART: THE ARTIFICIAL FECUNDATIONS 3rd SECTION: THE SYMBOLIC IMAGINARY AND THE REPRESENTATION OF THE SACRED Chap.5: The figurative vision of Buddhism Chap.6: The aesthetic tradition of Greek sculpture 4th SECTION: THE PRECIPITATE IN SPACE -

What the Romans Knew Piero Scaruffi Copyright 2018 • Part II

What the Romans knew Piero Scaruffi Copyright 2018 http://www.scaruffi.com/know • Part II 1 What the Romans knew Archaic Roma Capitolium Forum 2 (Museo della Civiltà Romana, Roma) What the Romans Knew • Greek! – Wars against Carthage resulted in conquest of the Phoenician and Greek civilizations – Greek pantheon (Zeus=Jupiter, Juno = Hera, Minerva = Athena, Mars= Ares, Mercury = Hermes, Hercules = Heracles, Venus = Aphrodite,…) – Greek city plan (agora/forum, temples, theater, stadium/circus) – Beginning of Roman literature: the translation and adaptation of Greek epic and dramatic poetry (240 BC) – Beginning of Roman philosophy: adoption of Greek schools of philosophy (155 BC) – Roman sculpture: Greek sculpture 3 What the Romans Knew • Greek! – Greeks: knowing over doing – Romans: doing over knowing (never translated Aristotle in Latin) – “The day will come when posterity will be amazed that we remained ignorant of things that will to them seem so plain” (Seneca, 1st c AD) – Impoverished mythology – Indifference to metaphysics – Pragmatic/social religion (expressing devotion to the state) 4 What the Romans Knew • Greek! – Western civilization = the combined effect of Greece's construction of a new culture and Rome's destruction of all other cultures. 5 What the Romans Knew • The Mediterranean Sea (Mare Nostrum) – Rome was mainly a sea power, an Etruscan legacy – Battle of Actium (31 BC) created the “mare nostrum”, a peaceful, safe sea for trade and communication – Disappearance of piracy – Sea routes were used by merchants, soldiers, -

Hasmonean” Family Tree

THE “HASMONEAN” FAMILY TREE Hasmoneus │ Simeon │ John │ Mattathias ┌──────────────┬─────────────────────┼─────────────────┬─────────┐ John Simon Judas Maccabee Eleazar Jonathan Murdered: Murdered: KIA: KIA: Murdered: 160/159 BC 134 BC 160 BC 162 BC 143 BC ┌────────┬────┴────┐ Judas John Hyrcanus Murdered: Murdered: Died: 134 BC 135 BC 104 BC ├──────────────────────┬─────────────┐ Aristobulus ═ Salome Alexander Antigonus Alexander ═══════ Salome Alexander Declared Himself “King”: Murdered: Declared “King”: Declared “Regent”: 104 BC 103 BC 103 BC 76 BC Died: Died: 103 BC 76 BC ┌──────┴──────┐ Hyrcanus II Aristobulus II Declared High Priest: 76 BC 1 THE “HASMONEAN” DYNASTY OF SIMON THE HIGH PRIEST 142 BC Simon, the last of the sons of Mattathias, was declared High Priest & “Ethnarch” (ruler of one’s own ethnic group) of the Jews by Demetrius II, King of the Seleucid Empire. 138 BC After Demetrius II was captured by the Parthians, his brother, Antiochus VII, affirmed Simon’s High Priesthood & requested assistance in dealing with Trypho, a usurper of the Seleucid throne. “King Antiochus to Simon the high priest and ethnarch and to the nation of the Jews, greetings. “Whereas certain scoundrels have gained control of the kingdom of our ancestors, and I intend to lay claim to the kingdom so that I may restore it as it formerly was, and have recruited a host of mercenary troops and have equipped warships, and intend to make a landing in the country so that I may proceed against those who have destroyed our country and those who have devastated many cities in my kingdom, now therefore I confirm to you all the tax remissions that the kings before me have granted you, and a release from all the other payments from which they have released you. -

The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2012 Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier Wai Kit Wicky Tse University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian History Commons, Asian Studies Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Tse, Wai Kit Wicky, "Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier" (2012). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 589. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/589 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/589 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier Abstract As a frontier region of the Qin-Han (221BCE-220CE) empire, the northwest was a new territory to the Chinese realm. Until the Later Han (25-220CE) times, some portions of the northwestern region had only been part of imperial soil for one hundred years. Its coalescence into the Chinese empire was a product of long-term expansion and conquest, which arguably defined the egionr 's military nature. Furthermore, in the harsh natural environment of the region, only tough people could survive, and unsurprisingly, the region fostered vigorous warriors. Mixed culture and multi-ethnicity featured prominently in this highly militarized frontier society, which contrasted sharply with the imperial center that promoted unified cultural values and stood in the way of a greater degree of transregional integration. As this project shows, it was the northwesterners who went through a process of political peripheralization during the Later Han times played a harbinger role of the disintegration of the empire and eventually led to the breakdown of the early imperial system in Chinese history. -

Banbhore) (200 Bc to 200 Ad)

INTERNATIONAL TRADE OF SINDH FROM ITS PORT BARBARICON (BANBHORE) (200 BC TO 200 AD) BY M.H. PANHWAR This period covers the rule of Bactrian Greeks, Scythians, Parthians and Kushans in Sindh, rest of the present Pakistan and parts of India. The origins of the development of European trade in the Sindh and trade routes under notice go back to later part of the sixth century BC, and it involved continuous efforts over next seven centuries. (a) After Darius-I’s conquest of Gandhara and Sindhu, admiral Skylax (a Greek of Caryanda), made exploratory voyage down the Kabul and the Indus from Kaspapyrus or Kasyabapura (Peshawar) to the Sindh coast and thence along the Arabian coast to the Red Sea and Egypt in 518 BC, completing the journey in 2 1/2 years and returning to Iran in 514 BC. The voyage was meant to connect the South Asia with Egypt. Darius-I also restored Necho-II’s canal connecting the Nile with the Red Sea. Thus he made Egypt and not Mesopotamia the main line of communication between the Indian and the Mediterranean Oceans. Darius built ‘the Royal Road’ connecting various cities of the empire. It ran the distance of 1677 well-garrisoned miles from Euphesus to Susa. A much longer route than this was from Babylon to Ecbatans and from thence to Kabul, which was already connected with Peshawar. The great voyage of Skylax connected Peshawar with the Red Sea and Egypt, via the Indus and the Arabian Sea. The earlier Egyptian navigation under Pharaohs had purely utilitarian and limited objectives were in no way similar to the great historical voyages, like one by Skylax, for general exploration. -

THE SANCTUARY at EPIDAUROS and CULT-BASED NETWORKING in the GREEK WORLD of the FOURTH CENTURY B.C. a Thesis Presented in Partial

THE SANCTUARY AT EPIDAUROS AND CULT-BASED NETWORKING IN THE GREEK WORLD OF THE FOURTH CENTURY B.C. A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University by Pamela Makara, B.A. The Ohio State University 1992 Master's Examination Committee: Approved by Dr. Timothy Gregory Dr. Jack Ba I cer Dr. Sa u I Corne I I VITA March 13, 1931 Born - Lansing, Michigan 1952 ..... B.A. in Education, Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan 1952-1956, 1966-Present Teacher, Detroit, Michigan; Rochester, New York; Bowling Green, Ohio 1966-Present ............. University work in Education, Art History, and Ancient Greek and Roman History FIELDS OF STUDY Major Field: History Studies in Ancient Civi I izations: Dr. Timothy Gregory and Dr. Jack Balcer i i TABLE OF CONTENTS VITA i i LIST OF TABLES iv CHAPTER PAGE I. INTRODUCTION 1 I I. ANCIENT EPIDAUROS AND THE CULT OF ASKLEPIOS 3 I II. EPIDAURIAN THEARODOKOI DECREES 9 IV. EPIDAURIAN THEOROI 21 v. EPIDAURIAN THEARODOKOI INSCRIPTIONS 23 VI. AN ARGIVE THEARODOKOI INSCRIPTION 37 VII. A DELPHIC THEARODOKOI INSCRIPTION 42 VIII. SUMMARY 47 END NOTES 49 BIBLIOGRAPHY 55 APPENDICES A. EPIDAURIAN THEARODOKOI INSCRIPTIONS AND TRANSLATIONS 58 B. ARGIVE THEARODOKO I I NSCR I PT I ON 68 C. DELPHIC THEARODOKOI INSCRIPTION 69 D. THEARODOKO I I NSCR I PT IONS PARALLELS 86 iii LIST OF TABLES TABLE PAGE 1. Thearodoko i I nscr i pt ions Para I I e Is •••••••••••• 86 iv CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION Any evidence of I inkage in the ancient world is valuable because it clarifies the relationships between the various peoples of antiquity and the dealings they had with one another. -

Iran (Persia) and Aryans Part - 1

INDIA (BHARAT) - IRAN (PERSIA) AND ARYANS PART - 1 Dr. Gaurav A. Vyas This book contains the rich History of India (Bharat) and Iran (Persia) Empire. There was a time when India and Iran was one land. This book is written by collecting information from various sources available on the internet. ROOTSHUNT 15, Mangalyam Society, Near Ocean Park, Nehrunagar, Ahmedabad – 380 015, Gujarat, BHARAT. M : 0091 – 98792 58523 / Web : www.rootshunt.com / E-mail : [email protected] Contents at a glance : PART - 1 1. Who were Aryans ............................................................................................................................ 1 2. Prehistory of Aryans ..................................................................................................................... 2 3. Aryans - 1 ............................................................................................................................................ 10 4. Aryans - 2 …............................………………….......................................................................................... 23 5. History of the Ancient Aryans: Outlined in Zoroastrian scriptures …….............. 28 6. Pre-Zoroastrian Aryan Religions ........................................................................................... 33 7. Evolution of Aryan worship ....................................................................................................... 45 8. Aryan homeland and neighboring lands in Avesta …...................……………........…....... 53 9. Western -

Early Career and Different Achievements of Asoka

International Journal of Research in Social Sciences Vol. 7 Issue 9, September 2017, ISSN: 2249-2496 Impact Factor: 7.081 Journal Homepage: http://www.ijmra.us, Email: [email protected] Double-Blind Peer Reviewed Refereed Open Access International Journal - Included in the International Serial Directories Indexed & Listed at: Ulrich's Periodicals Directory ©, U.S.A., Open J-Gage as well as in Cabell’s Directories of Publishing Opportunities, U.S.A Early career and different achievements of Asoka Manoj Malakar* Abstract Asoka was the greatest emperor in Mauriyan dynesty. He was a great patronage of Buddhism and art and architecture. This paper tries to high light about the early life and career of the great Mauryan emperor Asoka. There was lot of great emperor in Indian history, who wrote their name in golden letter in history and Asoka also one of among these rulers. Some different prominent writer had analysis about Asoka’s life and career. This paper tries to analyses how he (Asoka) began his career and got achievements during his region. This paper also tries to highlight Asoka’s Dhamma and his patronage of art and architecture during his region. This paper also tries to discuss Asoka’s patronage of Buddhism. He sent his own son and girl to Sri Lanka to spread Buddhism. Keywords: Career, Buddha Dhamma, Art and Architecture, Inscription. * Assistant Teacher & Faculty K.K.H.S.O.U. (Malaybari junior college study centre). 624 International Journal of Research in Social Sciences http://www.ijmra.us, Email: [email protected] ISSN: 2249-2496 Impact Factor: 7.081 Introduction Asoka was one of the greatest kings of India. -

Calendar of Roman Events

Introduction Steve Worboys and I began this calendar in 1980 or 1981 when we discovered that the exact dates of many events survive from Roman antiquity, the most famous being the ides of March murder of Caesar. Flipping through a few books on Roman history revealed a handful of dates, and we believed that to fill every day of the year would certainly be impossible. From 1981 until 1989 I kept the calendar, adding dates as I ran across them. In 1989 I typed the list into the computer and we began again to plunder books and journals for dates, this time recording sources. Since then I have worked and reworked the Calendar, revising old entries and adding many, many more. The Roman Calendar The calendar was reformed twice, once by Caesar in 46 BC and later by Augustus in 8 BC. Each of these reforms is described in A. K. Michels’ book The Calendar of the Roman Republic. In an ordinary pre-Julian year, the number of days in each month was as follows: 29 January 31 May 29 September 28 February 29 June 31 October 31 March 31 Quintilis (July) 29 November 29 April 29 Sextilis (August) 29 December. The Romans did not number the days of the months consecutively. They reckoned backwards from three fixed points: The kalends, the nones, and the ides. The kalends is the first day of the month. For months with 31 days the nones fall on the 7th and the ides the 15th. For other months the nones fall on the 5th and the ides on the 13th.