And the 'Long Eighth Century'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Islamic Art from the Collection, Oct. 23, 2020 - Dec

It Comes in Many Forms: Islamic Art from the Collection, Oct. 23, 2020 - Dec. 18, 2021 This exhibition presents textiles, decorative arts, and works on paper that show the breadth of Islamic artistic production and the diversity of Muslim cultures. Throughout the world for nearly 1,400 years, Islam’s creative expressions have taken many forms—as artworks, functional objects and tools, decoration, fashion, and critique. From a medieval Persian ewer to contemporary clothing, these objects explore migration, diasporas, and exchange. What makes an object Islamic? Does the artist need to be a practicing Muslim? Is being Muslim a religious expression or a cultural one? Do makers need to be from a predominantly Muslim country? Does the subject matter need to include traditionally Islamic motifs? These objects, a majority of which have never been exhibited before, suggest the difficulty of defining arts from a transnational religious viewpoint. These exhibition labels add honorifics whenever important figures in Islam are mentioned. SWT is an acronym for subhanahu wa-ta'ala (glorious and exalted is he), a respectful phrase used after every mention of Allah (God). SAW is an acronym for salallahu alayhi wa-sallam (may the blessings and the peace of Allah be upon him), used for the Prophet Muhammad, the founder and last messenger of Islam. AS is an acronym for alayhi as-sallam (peace be upon him), and is used for all other prophets before him. Tayana Fincher Nancy Elizabeth Prophet Fellow Costume and Textiles Department RISD Museum CHECKLIST OF THE EXHIBITION Spanish Tile, 1500s Earthenware with glaze 13.5 x 14 x 2.5 cm (5 5/16 x 5 1/2 x 1 inches) Gift of Eleanor Fayerweather 57.268 Heavily chipped on its surface, this tile was made in what is now Spain after the fall of the Nasrid Kingdom of Granada (1238–1492). -

The Athenian Agora

Excavations of the Athenian Agora Picture Book No. 12 Prepared by Dorothy Burr Thompson Produced by The Stinehour Press, Lunenburg, Vermont American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 1993 ISBN 87661-635-x EXCAVATIONS OF THE ATHENIAN AGORA PICTURE BOOKS I. Pots and Pans of Classical Athens (1959) 2. The Stoa ofAttalos II in Athens (revised 1992) 3. Miniature Sculpturefrom the Athenian Agora (1959) 4. The Athenian Citizen (revised 1987) 5. Ancient Portraitsfrom the Athenian Agora (1963) 6. Amphoras and the Ancient Wine Trade (revised 1979) 7. The Middle Ages in the Athenian Agora (1961) 8. Garden Lore of Ancient Athens (1963) 9. Lampsfrom the Athenian Agora (1964) 10. Inscriptionsfrom the Athenian Agora (1966) I I. Waterworks in the Athenian Agora (1968) 12. An Ancient Shopping Center: The Athenian Agora (revised 1993) I 3. Early Burialsfrom the Agora Cemeteries (I 973) 14. Graffiti in the Athenian Agora (revised 1988) I 5. Greek and Roman Coins in the Athenian Agora (1975) 16. The Athenian Agora: A Short Guide (revised 1986) French, German, and Greek editions 17. Socrates in the Agora (1978) 18. Mediaeval and Modern Coins in the Athenian Agora (1978) 19. Gods and Heroes in the Athenian Agora (1980) 20. Bronzeworkers in the Athenian Agora (1982) 21. Ancient Athenian Building Methods (1984) 22. Birds ofthe Athenian Agora (1985) These booklets are obtainable from the American School of Classical Studies at Athens c/o Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, N.J. 08540, U.S.A They are also available in the Agora Museum, Stoa of Attalos, Athens Cover: Slaves carrying a Spitted Cake from Market. -

Pre-Islamic Arabia

Pre-Islamic Arabia The Nomadic Tribes of Arabia The nomadic pastoralist Bedouin tribes inhabited the Arabian Peninsula before the rise of Islam around 700 CE. LEARNING OBJECTIVES Describe the societal structure of tribes in Arabia KEY TAKEAWAYS Key Points Nomadic Bedouin tribes dominated the Arabian Peninsula before the rise of Islam. Family groups called clans formed larger tribal units, which reinforced family cooperation in the difficult living conditions on the Arabian peninsula and protected its members against other tribes. The Bedouin tribes were nomadic pastoralists who relied on their herds of goats, sheep, and camels for meat, milk, cheese, blood, fur/wool, and other sustenance. The pre-Islamic Bedouins also hunted, served as bodyguards, escorted caravans, worked as mercenaries, and traded or raided to gain animals, women, gold, fabric, and other luxury items. Arab tribes begin to appear in the south Syrian deserts and southern Jordan around 200 CE, but spread from the central Arabian Peninsula after the rise of Islam in the 630s CE. Key Terms Nabatean: an ancient Semitic people who inhabited northern Arabia and Southern Levant, ca. 37–100 CE. Bedouin: a predominantly desert-dwelling Arabian ethnic group traditionally divided into tribes or clans. Pre-Islamic Arabia Pre-Islamic Arabia refers to the Arabian Peninsula prior to the rise of Islam in the 630s. Some of the settled communities in the Arabian Peninsula developed into distinctive civilizations. Sources for these civilizations are not extensive, and are limited to archaeological evidence, accounts written outside of Arabia, and Arab oral traditions later recorded by Islamic scholars. Among the most prominent civilizations were Thamud, which arose around 3000 BCE and lasted to about 300 CE, and Dilmun, which arose around the end of the fourth millennium and lasted to about 600 CE. -

Constructing the Seventh Century

COLLÈGE DE FRANCE – CNRS CENTRE DE RECHERCHE D’HISTOIRE ET CIVILISATION DE BYZANCE TRAVAUX ET MÉMOIRES 17 constructing the seventh century edited by Constantin Zuckerman Ouvrage publié avec le concours de la fondation Ebersolt du Collège de France et de l’université Paris-Sorbonne Association des Amis du Centre d’Histoire et Civilisation de Byzance 52, rue du Cardinal-Lemoine – 75005 Paris 2013 PREFACE by Constantin Zuckerman The title of this volume could be misleading. “Constructing the 7th century” by no means implies an intellectual construction. It should rather recall the image of a construction site with its scaffolding and piles of bricks, and with its plentiful uncovered pits. As on the building site of a medieval cathedral, every worker lays his pavement or polishes up his column knowing that one day a majestic edifice will rise and that it will be as accomplished and solid as is the least element of its structure. The reader can imagine the edifice as he reads through the articles collected under this cover, but in this age when syntheses abound it was not the editor’s aim to develop another one. The contributions to the volume are regrouped in five sections, some more united than the others. The first section is the most tightly knit presenting the results of a collaborative project coordinated by Vincent Déroche. It explores the different versions of a “many shaped” polemical treatise (Dialogica polymorpha antiiudaica) preserved—and edited here—in Greek and Slavonic. Anti-Jewish polemics flourished in the seventh century for a reason. In the centuries-long debate opposing the “New” and the “Old” Israel, the latter’s rejection by God was grounded in an irrefutable empirical proof: God had expelled the “Old” Israel from its promised land and given it to the “New.” In the first half of the seventh century, however, this reasoning was shattered, first by the Persian conquest of the Holy Land, which could be viewed as a passing trial, and then by the Arab conquest, which appeared to last. -

How Could Phenological Records from the Chinese Poems of the Tang and Song Dynasties

https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-2020-122 Preprint. Discussion started: 28 September 2020 c Author(s) 2020. CC BY 4.0 License. How could phenological records from the Chinese poems of the Tang and Song Dynasties (618-1260 AD) be reliable evidence of past climate changes? Yachen Liu1, Xiuqi Fang2, Junhu Dai3, Huanjiong Wang3, Zexing Tao3 5 1School of Biological and Environmental Engineering, Xi’an University, Xi’an, 710065, China 2Faculty of Geographical Science, Key Laboratory of Environment Change and Natural Disaster MOE, Beijing Normal University, Beijing, 100875, China 3Key Laboratory of Land Surface Pattern and Simulation, Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research, Chinese Academy of Science (CAS), Beijing, 100101, China 10 Correspondence to: Zexing Tao ([email protected]) Abstract. Phenological records in historical documents have been proved to be of unique value for reconstructing past climate changes. As a literary genre, poetry reached its peak period in the Tang and Song Dynasties (618-1260 AD) in China, which could provide abundant phenological records in this period when lacking phenological observations. However, the reliability of phenological records from 15 poems as well as their processing methods remains to be comprehensively summarized and discussed. In this paper, after introducing the certainties and uncertainties of phenological information in poems, the key processing steps and methods for deriving phenological records from poems and using them in past climate change studies were discussed: -

The Migration of Syrian and Palestinian Populations in the 7Th Century: Movement of Individuals and Groups in the Mediterranean

Chapter 10 The Migration of Syrian and Palestinian Populations in the 7th Century: Movement of Individuals and Groups in the Mediterranean Panagiotis Theodoropoulos In 602, the Byzantine emperor Maurice was dethroned and executed in a mili- tary coup, leading to the takeover of Phokas. In response to that, the Sasanian Great King Khosrow ii (590–628), who had been helped by Maurice in 591 to regain his throne from the usurper Bahram, launched a war of retribution against Byzantium. In 604 taking advantage of the revolt of the patrikios Nars- es against Phokas, he captured the city of Dara. By 609, the Persians had com- pleted the conquest of Byzantine Mesopotamia with the capitulation of Edes- sa.1 A year earlier, in 608, the Exarch of Carthage Herakleios the Elder rose in revolt against Phokas. His nephew Niketas campaigned against Egypt while his son, also named Herakleios, led a fleet against Constantinople. Herakleios managed to enter the city and kill Phokas. He was crowned emperor on Octo- ber 5, 610.2 Ironically, three days later on October 8, 610, Antioch, the greatest city of the Orient, surrendered to the Persians who took full advantage of the Byzantine civil strife.3 A week later Apameia, another great city in North Syria, came to terms with the Persians. Emesa fell in 611. Despite two Byzantine counter at- tacks, one led by Niketas in 611 and another led by Herakleios himself in 613, the Persian advance seemed unstoppable. Damascus surrendered in 613 and a year later Caesarea and all other coastal towns of Palestine fell as well. -

MEDIEVAL DAMASCUS Arabic Book Culture, Library Culture and Reading Culture Is Significantly Enriched.’ Li Guo, University of Notre Dame and MEDIEVAL

PLURALITY KONRAD HIRSCHLER ‘This is a tour de force of ferocious codex dissection, relentless bibliographical probing and imaginative reconstructive storytelling. Our knowledge of medieval MEDIEVAL DAMASCUS DAMASCUS MEDIEVAL Arabic book culture, library culture and reading culture is significantly enriched.’ Li Guo, University of Notre Dame AND MEDIEVAL The first documented insight into the content and DIVERSITY structure of a large-scale medieval Arabic library The written text was a pervasive feature of cultural practices in the medieval Middle East. At the heart of book circulation stood libraries that experienced a rapid expansion from the DAMASCUS twelfth century onwards. While the existence of these libraries is well known, our knowledge of their content and structure has been very limited as hardly any medieval Arabic catalogues have been preserved. This book discusses the largest and earliest medieval library of the PLURALITY AND Middle East for which we have documentation – the Ashrafiya library in the very centre of IN AN Damascus – and edits its catalogue. The catalogue shows that even book collections attached to Sunni religious institutions could hold very diverse titles, including Muʿtazilite theology, DIVERSITY IN AN Shiʿite prayers, medical handbooks, manuals for traders, stories from the 1001 Nights and texts extolling wine consumption. ARABIC LIBRARY ARABIC LIBRARY Listing over two thousand books the Ashrafiya catalogue is essential reading for anybody interested in the cultural and intellectual history of Arabic societies. -

Part of Princeton's Climate Change & History Research Initiative

The climate of survival? Environment, climate and society in Byzantine Anatolia, ca. 600-1050 Part of Princeton's Climate Change & History Research Initiative J. Haldon History Department, Princeton University, USA Project Team: Tim Newfield (Princeton); Lee Mordechai (Princeton) Introduction Problem and context No-one doubts that climate, environment and societal development are Between the early 630s and 740s the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) empire lost some The onset of this simplification cannot be made to coincide either with known political linked in causally complex ways. The problem is in the actual mechanics 75% of its territory (Fig. 2) and an equivalent amount in annual revenue to the events, such as the Arab invasions, nor can it be made to fit neatly with any single linking the two, and in trying to determine the causal associations, or in Arab-Islamic conquests or, in the Balkans, to various ‘barbarian’ groups. How did it ‘climate change’ event. In some areas the simplified regime does indeed coincide assigning these causal factors some order of priority. Key questions survive such a catastrophic loss, and how was it able to recover stability and go with the onset of the more humid conditions, in others it begins much later, and in include, for example, at what scale are the climatic and environmental onto the offensive in the later 9th and 10th centuries? There are many factors, as others there is no change at all. So a first conclusion must be that while some farmers events observed, and how does this relate to the societal changes in noted already, but environmental aspects have hitherto been largely disregarded. -

Christian Apologetics and the Gradual Restriction of Dhimmi Social Religious Liberties from the Arab-Muslim Conquests to the Abbasid Era Michael J

Eastern Michigan University DigitalCommons@EMU Master's Theses, and Doctoral Dissertations, and Master's Theses and Doctoral Dissertations Graduate Capstone Projects 2017 Shifting landscapes: Christian apologetics and the gradual restriction of dhimmi social religious liberties from the Arab-Muslim conquests to the Abbasid era Michael J. Rozek Follow this and additional works at: http://commons.emich.edu/theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Rozek, Michael J., "Shifting landscapes: Christian apologetics and the gradual restriction of dhimmi social religious liberties from the Arab-Muslim conquests to the Abbasid era" (2017). Master's Theses and Doctoral Dissertations. 863. http://commons.emich.edu/theses/863 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses, and Doctoral Dissertations, and Graduate Capstone Projects at DigitalCommons@EMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses and Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@EMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Shifting Landscapes: Christian Apologetics and the Gradual Restriction of Dhimmī Social-Religious Liberties from the Arab-Muslim Conquests to the Abbasid Era by Michael J. Rozek Thesis Submitted to the Department of History Eastern Michigan University in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER of History in History Thesis Committee: Philip C. Schmitz, Ph.D, Chair John L. Knight, Ph.D April 21, 2017 Ypsilanti, Michigan Abstract This historical research study explores the changes of conquered Christians’ social-religious liberties from the first interactions between Christians and Arab-Muslims during the conquests c. A.D. 630 through the the ‘Abbasid era c. -

Mclaren 650S DIALS up PERFORMANCE and EXCITEMENT

Media Information EMBARGOED: 11:15.GMT, 4 March 2014 McLAREN 650S DIALS UP PERFORMANCE AND EXCITEMENT Developed to give the enthusiast driver the ultimate in luxury, engagement and excitement…on road and track Offers the widest breadth of capabilities of any supercar Design and engineering inspired by the groundbreaking McLaren P1™ Joins McLaren’s range of supercars above 12C, which continues on sale Coupé and Spider, with electrically retractable hard top, to be available from Spring 2014 launch McLaren Automotive will return to the International Geneva Motor Show this year with its fastest, most engaging, best equipped and most beautiful series-production supercar yet. The McLaren 650S joins the range as an additional model alongside the 12C and sold-out McLaren P1™, and learns from both models as well as 50 years of competing in the highest levels of motorsport. Available as a fixed-head Coupé or as a Spider, with a retractable folding hard top, the McLaren 650S promises to redefine the high performance supercar segment, and has been designed and developed to provide the ultimate in driver engagement on the road and on the race track. The 650S badge designation refers to the power output – 650PS (641 bhp), - of the unique British-built McLaren M838T twin turbo V8 engine. ‘S’ stands for ‘Sport’, underlining the focus and developments made to handling, transmission, drivability and engagement. The maximum power figure ensures the best power-to-weight ratio in its class, at 500PS (493 bhp) per tonne. The design is inspired by the McLaren P1™, showcasing a new family design language for the brand. -

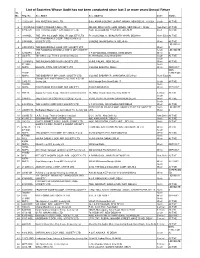

List of Societies Not Audited for Last 3 Years Or More/Annual Return

List of Societies Whose Audit has not been conducted since last 3 or more years/Annual Return Sr. No. Reg. No. Soc. Name Soc. Address Zone Status 1 1232S-GH NAV NIKETAN CGHS LTD B-83, AMAR COLONY, LAJPAT NAGAR, NEW DELHI : 110 024 South ACTIVE 2 1451ND-GH PREETI PRISHAD CGHS LTD. DB-84E, DDA FLATS, HARI NAGAR, NEW DELHI: 110 063 New Delhi ACTIVE 3 875E-GH NAV TARANG COOP. G/H SOCIETY LTD H-26, OLD GOBIND PURA EXT.,DELHI-51 East ACTIVE 4 724-INDL THE JAIN H/L COOP. INDL. (P) SOCIETY LTD. F413 GALI NO. 11, BHAGIRATH VIHAR, DELHI-94 North East ACTIVE THE BAKARWALA COOP. BRICKS KILN (I) 5 24W-INDL SOCIETY LTD. SURERE, NAJAFGARH, N. DELHI-43 West ACTIVE LIQUIDATE 6 24W-NMPS THE BAKARWALA COOP. M/P SOCIETY LTD. West D THE PANDWAL KHOODS COOP N.M.P SOCIETY South LIQUIDATE 7 32-NMPS LTD V.P.O PANDWAL KHOODS, NEW DELHI West D 8 505S-TC The Sikh Coop. Thrift & Credit Society Ltd. 61, Hemkunt Colony, New Delhi- South ACTIVE South 9 124-NMPS THE PALAM COOP N.M.P SOCIETY LTD V&PO, PALAM , NEW DELHI West ACTIVE 211NW- North 10 NMPS BAKAOLI COOL M/P SOCIETY LTD VILLAGE BAKAOLI, DELHI West DEFUNCT NON- 216NE- FUNCTION 11 NMPS THE BABARPUR M/P COOP. SOCIETY LTD. VILLAGE BABARPUR, SHAHDARA, DELHI-32 North East AL Chiragh Delhi Palti Yadram Coop. Thrift & Credit 12 230S-TC Sociey Ltd. 830 Chiragh Delhi,New Delhi-17 South ACTIVE 138NW- North 13 NMPS BUKHTAWAR PUR COOP. -

Gender and Moral Authority in the Carolingian Age (2016)

NOTICE: The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of reproductions of copyrighted material. One specified condition is that the reproduction is not to be "used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research." If a user makes a request for, or later uses a reproduction for purposes in excess of "fair use," that user may be liable for copyright infringement. RESTRICTIONS: This student work may be read, quoted from, cited, for purposes of research. It may not be published in full except by permission of the author. 1 INTRODUCTION The common people call the place, both the spring and the village, Fontenoy, Where that massacre and bloody downfall of the Franks [took place]: The fields tremble, the woods tremble, the very swamp trembles… Let not that accursed day be counted in the calendar of the year, Rather let it be erased from all memory, May the sun’s rays never fall there, may no dawn ever come to [end its endless] twilight. -Englebert, 8411 The Battle of Fontenoy in 841 left the Carolingian Empire devastated. It was the only battle of a three-year civil war that left too many dead and the survivors, shattered. During this period of unrest, from 840-843, an aristocratic woman, Dhuoda, endured the most difficult years of her life. The loyalty of her absentee husband, Bernard of Septimania, was being questioned by one of the three kings fighting for an upper-hand in this bloody civil war. To ensure his loyalty, his and Dhuoda’s 14-year old son, William, was to be sent to King Charles the Bald as a hostage.