Early Observation of the a Urora Australis: AD 1640

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biografías Y Bibliografías De Naturalistas Y Antropólogos, Principalmente De Chile, Publi- Cadas Por Don Carlos E

GUALTERIO LOOSER Biografías y bibliografías de naturalistas y antropólogos, principalmente de Chile, publi- cadas por don Carlos E. Porter LSD Santiago de Chile Imprenta Universitaria 19 4 9 APARTAD3 DE I.A «REVISTA CHILENA DE HISTORIA Y GEOGRAFÍA N.° 113. 1049. Biografías y bibliografías de naturalistas y an- tropólogos, principalmente de Chile, publica- das por don Carlos E. Porter La idea de hacer esta recopilación bibliográfica se debe a una insinuación del eminente naturalista holandés y biblió- grafo de las ciencias iKiturales, Dr. Frans Yerdoorn, editor de la importante revista Chronica Botanica, de la obra Plants and Plant Science in Latín America y otras publicaciones in- ternacionales. Se quejaba el Dr. Verdoorn de las grandes di- ficultades que se presentan al investigador en Europa, KK. UU., etc., para encontrar datos fidedignos sobre los hombres de ciencia de la América Latina. Ale rogaba le enviara datos relativos a los botánicos chilenos y llamaba mi atención ha- cia la importancia de las biografías y bibliografías que el Prof. Dr. D. Carlos K. Porter había publicado en la Revista Chilena de Historia Natural, fundada por él en 1897 y mante- nida con admirable constancia durante 45 años, hasta su muerte. Acogí con entusiasmo la insinuación del Dr. Verdoorn y me lancé a la tarea de formar una lista lo más completa posi- ble de los artículos biográficos y bibliográficos sobre natura- listas y antropólogos publicados por el Dr. Porter, tanto en la Revista Chilena de Historia Natural, como en otras partes. Un extracto de la sección botánica será enviado al Dr. Ver- doorn, para que lo utilice en sus obras bibliográficas; pero me pareció conveniente publicar el trabajo in extenso en Chile, enumerando no sólo las biobibliografías de los botánicos, sino IilOGRAFÍAS V BIJiLIOGRAF. -

Artículo Titulado Pocos Meses Que Lleva De Existencia

Revista Chilena de Historia Natural 61: 89-112, 1988 DOCUMENTO Carlos E. Porter, la Academia Chilena de Ciencias Naturales y los Anales de la Academia Chilena de Ciencias Naturales Carlos E. Porter, the Academia Chilena de Ciencias Naturales and the Anales de la Academia Chilena de Ciencias Naturales MARIA ETCHEVERR Y Irarrázaval1628, Depto. 94, Santiago, Chile En 1926, en la Revista Universitaria 11 (4): otras es el fruto de sus esfuerzos de los 237-246, se publica un artículo titulado pocos meses que lleva de existencia. El gran "Academia Chilena de Ciencias Naturales" premio, al más meritorio de nuestros natu- en el cual aparecen las dos primeras actas ralistas nacionales, fue adjudicado por la constitutivas de esta institución y el direc- unanimidad de la Academia a su Director torio y miembros de ella. Vitalicio y profesor nuestro, don Carlos En ese artículo se informa que el 8 de Porter". En el mismo tomo 12 ( 4 ), pág. mayo de 1926, a las 4.30 de la tarde, se 362, aparece: "Acta de la 11a sesión reunieron en el salón de la Biblioteca de la solemne efectuada el 28 de mayo de 1927 Universidad Católica, presididas por el Rec- en honor de su Director Vitalicio, don tor Monseñor D. Carlos Casanueva, varias Carlos E. Porter, para la entrega de la personas invitadas por él, con el fin de medalla que acordó la Academia". En esta estudiar las bases de la fundación de una acta se pueden leer entre otras cosas los Academia de Ciencias Naturales que coope- discursos del homenajeado y de don En- rara al progreso de estas ciencias en Chile. -

El Abate Juan Ignacio Molina Y Opazo: Su Descripción Del Reyno De Chile

Revista de Geografía Norte Grande, 22: 111-115 (1995) GALERIA GEOGRAFICA DE CHILE El Abate Juan Ignacio Molina y Opazo: Su Descripción del Reyno de Chile HUGO RODOLFO RAMIREZ RIVERA De la Academia Nacional Venezolana de la Historia RESUMEN El presente estudio tiene por objeto revisar descripcián que hicieron los cronistas del siglo XIX respecto a Chile. ABSTRACT This study attempts to review the description 01the Chilean territory made by the primitive historians in the XIXth Century. I. INTRODUCCION lineamientos más universales, producto del ra ciocinio, tenderá a enfocar los objetos de estudio Con la presente entrega damos término al desde una perspectiva sistematizadora. trabajo iniciado en los números anteriores de esta Uno de los exponentes más genuinos de todo revista sobre los autores y sus obras descriptivas esto es el Abate Juan Ignacio Malina y Opazo, del antiguo Reyno de Chile. En esta ocasión natural de Guaraculén, en Loncomilla, Reyno de damos a conocer la visión que hacia fines del siglo Chile. Ingresado a la Compañía de Jesús en la XVIII y comienzos del XIX tenía el ilustre sabio Ciudad de Santiago en 1756, debió correr la chileno Abate Don Juan Ignacio Malina y Opazo. suerte de sus demás hermanos de hábito, pasando a residenciarse en Italia, haciendo en Bolonia una 11.LOS AUTORES Y SUS OBRAS: importante carrera como hombre de estudio, sien do considerado por sus contemporáneos entre los Descripciones del Reyno de Chile sabios de su tiempo. Falleció en Bolonia el 12 de septiembre de 1829 1• Con el siglo XIX el desarrollo de las ciencias Preocupado como otros de sus compatriotas toma un más fuerte incremento como consecuen jesuitas expulsas de dar a conocer su país en cia del movimiento de la Ilustración, que había Europa, publicó anónimamente en Bolonia en sido el inicio de una nueva postura de apreciación 1776 un Compendio de la Historia Geográfica, del cosmos. -

El Abate Juan Ignacio Molina (1740-1829) Y Su Contribución a Las Ciencias Naturales De Chile

Gestión Ambiental 17: 1-9 (2009) EL ABATE JUAN IGNACIO MOLINA (1740-1829) Y SU CONTRIBUCIÓN A LAS CIENCIAS NATURALES DE CHILE The abbot Juan Ignacio Molina (1740-1829) and his contribution to the knowledge of natural science of Chile Manuel Tamayo Universidad Católica del Maule, Talca Chile. Correo electrónico: [email protected] Gestión Ambiental (Valdivia). ISSN 0718-445X versión en línea, ISSN 0717-4918 versión impresa. 1 Tamayo RESUMEN El sacerdote jesuita chileno, abate Juan Ignacio Molina (1740-1829), historiador, filósofo, zoólogo y botánico, se dedicó especialmente a la historia natural de Chile. Estudió lenguas e historia natural en un colegio de jesuitas. Dedicó años a la observación de la naturaleza y a la recopilación y descripción de plantas y animales chilenos. Debido a que a los jesuitas se les expulsó de los dominios de España, se fue desde Chile a Italia en 1768. Era experto en varios idiomas y gracias a ello se convirtió en profesor de la Universidad de Bolonia, miembro de la Academia Italiana de Ciencias y del Instituto de Italia. Publicó Saggio Sulla Storia Naturale del Chili en 1782, la primera obra maestra clásica de la historia natural de Chile, que trata de geografía, mineralogía, zoología y botánica. Durante muchos años esta obra fue una referencia esencial para interesados en la historia natural de Chile. El uso de nombres científicos en latín permitió la incorporación de un número importante de nombres propuestos por Molina a la taxonomía internacional. Nacido en Huaraculén, Chile, falleció en Bolonia, Italia. Palabras claves: Historia de la ciencia, biografía, naturalista chileno, historia natural de Chile. -

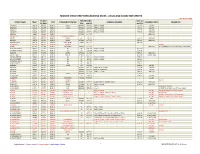

Residential Resurfacing List

MISSION VIEJO STREET RESURFACING INDEX - LOCAL AND COLLECTOR STREETS Rev. DEC 31, 2020 TB MAP RESURFACING LAST AC STREET NAME TRACT TYPE COMMUNITY/OWNER ADDRESS NUMBERS PAVEMENT INFO COMMENTS PG GRID TYPE MO/YR MO/YR ABADEJO 09019 892 E7 PUBLIC OVGA RPMSS1 OCT 18 28241 to 27881 JUL 04 .4AC/NS ABADEJO 09018 892 E7 PUBLIC OVGA RPMSS1 OCT 18 27762 to 27832 JUL 04 .4AC/NS ABANICO 09566 892 D2 PUBLIC RPMSS OCT 17 27551 to 27581 SEP 10 .35AC/NS ABANICO 09568 892 D2 PUBLIC RPMSS OCT 17 27541 to 27421 SEP 10 .35AC/NS ABEDUL 09563 892 D2 PUBLIC RPMSS OCT 17 .35AC/NS ABERDEEN 12395 922 C7 PRIVATE HIGHLAND CONDOS -- ABETO 08732 892 D5 PUBLIC MVEA AC JUL 15 JUL 15 .35AC/NS ABRAZO 09576 892 D3 PUBLIC MVEA RPMSS OCT 17 SEP 10 .35AC/NS ACACIA COURT 08570 891 J6 PUBLIC TIMBERLINE TRMSS OCT 14 AUG 08 ACAPULCO 12630 892 F1 PRIVATE PALMIA -- GATED ACERO 79-142 892 A6 PUBLIC HIGHPARK TRMSS OCT 14 .55AC/NS 4/1/17 TRMSS 40' S of MAQUINA to ALAMBRE ACROPOLIS DRIVE 06667 922 A1 PUBLIC AH AC AUG 08 24582 to 24781 AUG 08 ACROPOLIS DRIVE 07675 922 A1 PUBLIC AH AC AUG 08 24801 to 24861 AUG 08 ADELITA 09078 892 D4 PUBLIC MVEA RPMSS OCT 17 SEP 10 .35AC/NS ADOBE LANE 06325 922 C1 PUBLIC MVSRC RPMSS OCT 17 AUG 08 .17SAC/.58AB ADONIS STREET 06093 891 J7 PUBLIC AH AC SEP 14 24161 to 24232 SEP 14 ADONIS STREET 06092 891 J7 PUBLIC AH AC SEP 14 24101 to 24152 SEP 14 ADRIANA STREET 06092 891 J7 PUBLIC AH AC SEP 14 SEP 14 AEGEA STREET 06093 891 J7 PUBLIC AH AC SEP 14 SEP 14 AGRADO 09025 922 D1 PUBLIC OVGA AC AUG 18 AUG 18 .4AC/NS AGUILAR 09255 892 D1 PUBLIC RPMSS OCT 17 PINAVETE -

Permanent War on Peru's Periphery: Frontier Identity

id2653500 pdfMachine by Broadgun Software - a great PDF writer! - a great PDF creator! - http://www.pdfmachine.com http://www.broadgun.com ’S PERIPHERY: FRONT PERMANENT WAR ON PERU IER IDENTITY AND THE POLITICS OF CONFLICT IN 17TH CENTURY CHILE. By Eugene Clark Berger Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in History August, 2006 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: Date: Jane Landers August, 2006 Marshall Eakin August, 2006 Daniel Usner August, 2006 íos Eddie Wright-R August, 2006 áuregui Carlos J August, 2006 id2725625 pdfMachine by Broadgun Software - a great PDF writer! - a great PDF creator! - http://www.pdfmachine.com http://www.broadgun.com HISTORY ’ PERMANENT WAR ON PERU S PERIPHERY: FRONTIER IDENTITY AND THE POLITICS OF CONFLICT IN 17TH-CENTURY CHILE EUGENE CLARK BERGER Dissertation under the direction of Professor Jane Landers This dissertation argues that rather than making a concerted effort to stabilize the Spanish-indigenous frontier in the south of the colony, colonists and indigenous residents of 17th century Chile purposefully perpetuated the conflict to benefit personally from the spoils of war and use to their advantage the resources sent by viceregal authorities to fight it. Using original documents I gathered in research trips to Chile and Spain, I am able to reconstruct the debates that went on both sides of the Atlantic over funds, protection from ’ th pirates, and indigenous slavery that so defined Chile s formative 17 century. While my conclusions are unique, frontier residents from Paraguay to northern New Spain were also dealing with volatile indigenous alliances, threats from European enemies, and questions about how their tiny settlements could get and keep the attention of the crown. -

The Morgan's Role out West

THE MORGAN’S ROLE OUT WEST CELEBRATED AT VAQUERO HERITAGE DAYS 2012 By Brenda L. Tippin Stories of cowboys and the old west have always captivated Americans with their romance. The California vaquero was, in fact, America’s first cowboy and the Morgan horse was the first American breed regularly used by many of these early vaqueros. Renewed interest in the vaquero style of horsemanship in recent years has opened up huge new markets for breeders, trainers, and artisans, and the Morgan horse is stepping up to take his rightful place as an important part of California Vaquero Heritage. THE MORGAN CONNECTION and is becoming more widely recognized as what is known as the The Justin Morgan horse shared similar origins with the horses of “baroque” style horse, along with such breeds as the Andalusian, the Spanish conquistadors, who were the forefathers of the vaquero Lippizan, and Kiger Mustangs, which are all favored as being most traditions. The Conquistador horses, brought in by the Moors, like the horse of the Conquistadors. These breeds have the powerful, carried the blood of the ancient Barb, Arab, and Oriental horses— deep rounded body type; graceful arched necks set upright, coming the same predominant lines which may be found in the pedigree out of the top of the shoulder; and heavy manes and tails similar of Justin Morgan in Volume I of the Morgan Register. In recent to the European paintings of the Baroque period, which resemble years, the old style foundation Morgan has gained in popularity today’s original type Morgans to a remarkable degree. -

Stories of Words: Spanish

Stories of Words: Spanish By: Elfrieda H. Hiebert & Wendy Svec Stories of Words: Spanish, Second Edition © 2018 TextProject, Inc. Some rights reserved. ISBN: 978-1-937889-23-4 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ us/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. “TextProject” and the TextProject logo are trademarks of TextProject, Inc. Cover photo ©2016 istockphoto.com/valentinrussanov. All rights reserved. Used under license. 2 Contents Learning About Words ...............................4 Chapter 1: Everyday Sayings .....................5 Chapter 2: ¡Buen Apetito! ...........................8 Chapter 3: Cockroaches to Cowboys ......12 Chapter 4: ¡Vámonos! ...............................15 Chapter 5: It’s Raining Gatos & Perros!....18 Our Changing Language ..........................21 Glossary ...................................................22 Think About It ...........................................23 3 Learning About Words Hola! Welcome to America, where you can see and hear the Spanish language all around you. Look at street signs or on menus. You will probably see Spanish words or names. Listen to the radio or television. It is likely you will hear Spanish being spoken. Since Spanish-speaking people first arrived in North America in the 16th century, the Spanish language has been part of American culture. Some people are being raised in Spanish-speaking homes and communities. Other people are taking classes to learn to speak and read Spanish. As a result, Spanish has become the second most spoken language in the United States. Every day, millions of Americans are speaking Spanish. -

CHILE COMO UN “FLANDES INDIANO” EN LAS CRÓNICAS DE LOS SIGLOS XVI Y XVII1

REVISTA CHILENA DE LiteratURA Noviembre 2013, Número 85, 157-177 CHILE COMO UN “FLANDES INDIANO” EN LAS CRÓNICAS DE LOS SIGLOS XVI Y XVII1 Álvaro Baraibar GRISO - Universidad de Navarra [email protected] RESUMEN / ABSTRACT La idea de un nuevo Flandes o de un segundo Flandes o simplemente de otro Flandes apareció en diferentes momentos en el territorio de la Monarquía Hispánica referida a Aragón, Cataluña o Messina. El recuerdo de la guerra pervivió en el imaginario colectivo español más allá del final del conflicto, cuando Flandes era ya un aliado de la Corona española frente a Francia. Cuando en el desarrollo de la conquista de las Indias Occidentales Chile se convierte en el gran problema militar con motivo de la resistencia de los indígenas de la Araucanía, la idea de un segundo Flandes aparecerá también en tierras americanas. Este trabajo pretende mostrar el proceso y los contextos en que Flandes se hizo presente en el discurso que se elaboró sobre el Reino de Chile en las crónicas de los siglos XVI y XVII, hasta que Diego de Rosales acuñara el término “Flandes indiano”. PALABRAS CLAVE: Crónicas de Indias, reino de Chile, guerra, Flandes. The idea of a new Flanders or of a second or simply of another one appeared in different moments in the territory of Hispanic Monarchy referred to Aragón, Catalonia or Messina. The memory of this war survived in the Spanish collective imaginary even long after the end of the conflict, when Flanders was an ally of the Spanish Crown against France. When Chile becomes the great military problem due to native resistance to conquest, the idea of a second Flanders will turn up in America. -

Reflexiones En Torno Al Uso De Embarcaciones Monóxilas En

Reflexiones en torno al uso de embarcaciones monóxilas en ambientes boscosos lacustres precordilleranos andinos, zona centro-sur de Chile Diego Carabias, Nicolás Lira San Martin, Leonora Adán To cite this version: Diego Carabias, Nicolás Lira San Martin, Leonora Adán. Reflexiones en torno al uso de embarca- ciones monóxilas en ambientes boscosos lacustres precordilleranos andinos, zona centro-sur de Chile. Magallania, Universidad de Magallanes, 2010, 38 (1), pp.87-108. hal-01884677 HAL Id: hal-01884677 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01884677 Submitted on 1 Oct 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial| 4.0 International License MAGALLANIA, (Chile), 2010. Vol. 38(1):87-108 87 REFLEXIONES EN TORNO AL USO DE EMBARCACIONES MONÓXILAS EN AMBIENTES BOSCOSOS LACUSTRES PRECORDILLERANOS ANDINOS, ZONA CENTRO-SUR DE CHILE DIEGO CARABIAS A.*, NICOLÁS LIRA S.** Y LEONOR ADÁN A.*** RESUMEN El presente trabajo propone una refl exión en torno a las prácticas de navegación interior en los ambientes boscosos de lagos subandinos del centro-sur de Chile. Se realiza una revisión crítica de los antecedentes disponibles para estas tecnologías de transporte, y en particular, de las canoas monóxilas indígenas, desde la arqueología, la etnohistoria y la etnografía. -

Historia De La Literatura Colonial De Chile Tomo I

Historia de la literatura colonial de Chile Tomo I José Toribio Medina Primera parte Poesía (1541-1810) C'est qu'en effet, toujours et partont, la poésie de la vie humaine se résume en trois mots: religion, gloire, amour. MENNECHET, Matinées littèraires, I, p. 106. [VII] Introducción ¿Qué debe entenderse por literatura colonial de Chile?- Estado intelectual de Chile a la llegada de los españoles.- Oratoria araucana.- Carácter impreso a la literatura colonial por la guerra araucana.- Diferencia de otros pueblos de la América.- Doble papel de actores y escritores que representaron nuestros hombres.- Ingratitud de la corte.- Amor a Chile.- Encadenamiento en la vida de nuestros escritores.- Transiciones violentas que experimentaron.- Principios fatalistas.- Crueldades atribuidas a los conquistadores.- El teatro español y la conquista de Chile.- Creencia vulgar sobre la oposición que se suponía existir entre las armas y la pluma.- Condiciones favorables para escribir la historia.- Las obras de los escritores chilenos aparecen por lo general inconclusas.- Profesiones ordinarias de esos escritores.- Falta de espontaneidad que se nota en ellos.- Ilustración de algunos de nuestros gobernadores.- Errores bibliográficos.- Obras perdidas.- Ignorancia de nuestros autores acerca de lo que otros escribieron.- Dificultades de impresión.- Sistema de la corte.- El respeto a la majestad real.- Prohibición de leer obras de imaginación.- Id. de escribir impuesta a los indígenas.- Privación de la influencia extranjera.- Persecuciones de la corte.- Disposiciones legales.- Dedicatorias.- La crítica.- Respeto por la antigüedad.- Prurito de las citas.- Monotonía de la vida colonial.- La sociedad.- El gusto por la lectura.- Bibliotecas.- Preferencias por el latín.- Falta de estímulos.- Sociedades literarias.- Historia de la instrucción en Chile.- Id. -

El Jardín De La América Meridional»… Ciencia Como Deleite, Información Y El Encanto De Los Jardines Ingleses En Un Naturalista Chileno En El Illuminismo Italiano*

Revista de Indias, 2020, vol. LXXX, núm. 278 Págs. 131-162, ISSN: 0034-8341 https://doi.org/10.3989/revindias.2020.005 «El jardín de la América meridional»… ciencia como deleite, información y el encanto de los jardines ingleses en un naturalista chileno en el Illuminismo italiano* por Francisco Orrego González1 Universidad Andrés Bello, Chile El presente artículo quiere explorar en una de las diversas representaciones culturales que se elaboraron de la América meridional por uno de los tantos jesuitas expulsos en la Italia del Settecento como el naturalista e historiador chileno Juan Ignacio Molina (1740- 1829). La expresión metafórica «El jardín de la América», permite adentrarse en las contro- versias culturales en torno a un objeto histórico que los historiadores culturales poco han abordado una escenografía natural particular como es el jardín. El trabajo sostiene, por medio del estudio de la historia natural de Chile escrita por Molina, junto a una memoria defendida por él mismo en la Accademia delle Scienze de Bolonia relativa a los jardines in- gleses a inicios del siglo XIX, que el naturalista chileno fue un autor prerromántico gracias a las fuentes de información que utilizó para realizar estos trabajos en un escenario cultural particular como fue el Illuminismo italiano. Palabras clave: Juan Ignacio Molina; historia natural; jardines; fuentes de información; prerromanticismo. Cómo citar este artículo / Citation: Orrego González, Francisco, “«El jardín de la América meridional»… ciencia como deleite, información y el encanto de los jardines ingle- ses en un naturalista chileno en el Illuminismo italiano”, Revista de Indias, LXXX/278 (Ma- drid, 2020): 131-162.