Science As Culture, Cultures of Science

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Invented Or Inherited?

Call for Papers 12th UNEeCC Conference Culture: Invented or Inherited? 7-9 November 2018 University of Malta, Valletta Campus Culture is ‘the way-of-life in an ecosystem characteristic of a particular people’ (Keesing 1981:68). This is only one of the countless definitions given to this term which is ‘surprisingly’ and ‘notoriously’ difficult to define due to its dynamic nature (Smith and Riley 2011). Underlying dimensions characterising early and modern Europe, such as the economic situation of specific countries and humanitarian crises may be determining factors by which its collectivist culture has been constantly in flux, particularly in its production and consumption. One would question the affects which these factors may have on the transmission of traditional and popular European cultures and if their core components are, in fact, inherited or invented. The main objective of this conference is to develop critical arguments based on two concepts which can be non-homogenous and overlapping at the same time, namely (i) Culture inheritance and (ii) Cultural invention. Key questions relevant to this conference are: (i) ‘how does the concept of European Capitals of Culture consider the invention and inheritance of cultures?’; (ii) ‘What avenues are being taken by ECoC programmers to strike a balance in the promotion of cultural components which are ‘invented’ and those based on grass-root identities?’; and (iii) ‘What are the core arguments surrounding the questions of whether a culture is invented or inherited?. Established academics, -

Embracing Cyberculture on Graphic Design

Conference Proceeding: 2nd INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON CREATIVE MEDIA, DESIGN & TECHNOLOGY (REKA2016) EMBRACING CYBERCULTURE ON GRAPHIC DESIGN Nurul Hanim Romainoor 1 Universiti Sains Malaysia 1 [email protected] Sarena Abdullah 2 Universiti Sains Malaysia 2 [email protected] ABSTRACT This paper is about exploring the concept of Cyberculture on graphic design. Today, people from the different background of age and culture are engaged in using personal computers, smartphones, and even digital cameras. They are known as the active media users. They are the new inventors of graphic design, digital images, animation and films in cyberspace. This study uses a thematic lens to describe writings on popular Cyberculture. The interesting part of this section is the construction of cyberpunk and cyborg that engaged in many popular Cyberculture writings. Two lenses derived from popular Cyberculture were assessed; one is cyberpunk and two is the cyborg. These two lenses are the foundation for reviewing Cyberculture on graphic design and a reflection of graphic design involvement with the computer and the Internet are discussed. The finding on graphic design in the lens of Cyberpunk seen in design illustration of favourite comic characters. Where, active media users may transform the iconic characters into cyberpunk that portray dark colours with streaks of neon colours and lighting. While from the lens cyborg, a graphic design series can be seen in the conceptual digital art by fans illustrations that revolve around popular movies and TV series. When graphic design took notice of the cyberspace, it increased the popularity for active media users to implement a graphic design into their personal artwork. -

Tourism and Cultural Identity: the Case of the Polynesian Cultural Center

Athens Journal of Tourism - Volume 1, Issue 2 – Pages 101-120 Tourism and Cultural Identity: The Case of the Polynesian Cultural Center By Jeffery M. Caneen Since Boorstein (1964) the relationship between tourism and culture has been discussed primarily in terms of authenticity. This paper reviews the debate and contrasts it with the anthropological focus on cultural invention and identity. A model is presented to illustrate the relationship between the image of authenticity perceived by tourists and the cultural identity felt by indigenous hosts. A case study of the Polynesian Cultural Center in Laie, Hawaii, USA exemplifies the model’s application. This paper concludes that authenticity is too vague and contentious a concept to usefully guide indigenous people, tourism planners and practitioners in their efforts to protect culture while seeking to gain the economic benefits of tourism. It recommends, rather that preservation and enhancement of identity should be their focus. Keywords: culture, authenticity, identity, Pacific, tourism Introduction The aim of this paper is to propose a new conceptual framework for both understanding and managing the impact of tourism on indigenous host culture. In seminal works on tourism and culture the relationship between the two has been discussed primarily in terms of authenticity. But as Prideaux, et. al. have noted: “authenticity is an elusive concept that lacks a set of central identifying criteria, lacks a standard definition, varies in meaning from place to place, and has varying levels of acceptance by groups within society” (2008, p. 6). While debating the metaphysics of authenticity may have merit, it does little to guide indigenous people, tourism planners and practitioners in their efforts to protect culture while seeking to gain the economic benefits of tourism. -

Part Three Autoevolution and Posthumanism

Part Three Autoevolution and Posthumanism Pawe Majewski - 9783631710258 Downloaded from PubFactory at 09/23/2021 08:08:01PM via free access Pawe Majewski - 9783631710258 Downloaded from PubFactory at 09/23/2021 08:08:01PM via free access 17 Themes of Lampoon of Evolution In Part Three of this book I will discuss the last chapter of ST, and then some of the currents in contemporary philosophy and sociology, which in one way or another seem to be akin to Lem’s project of autoevolution. These are mostly convergences rather than any kind of genetic affinities, and will partly be constructed through my interpretations. The aim is to show that Lem’s work, especially ST, has great albeit so far unacknowledged significance for the con- temporary problems of our civilization. The last chapter of ST is titled “Lampoon of Evolution.” It includes a descrip- tion of the project of autoevolution of human species, the very description to which the rest of ST is but a set of introductory studies, as I have suggested ear- lier. The word “lampoon” ought to be taken with a grain of salt, just as other rhetorical devices Lem uses in the titles of his chapters and sections of ST. It is a testimony to Lem’s personal and internally diverse attitude to bioevolution. He both admires the phenomenon, which he often hypostatizes, and is critical and hostile to it. The admiration comes from the fact that bioevolution has pro- duced such amazing beings as a biological cell and rational humans.180 The crit- icism and hostility stem from the fact that for Lem the rationalist the process is unbearable in how blindly random it is. -

Why a Public Anthropology? Notes and References

WHY A PUBLIC ANTHROPOLOGY? NOTES AND REFERENCES While the placement of notes and references online is still relatively rare, they are quite easy to examine in a PDF online format. Readers should use find (or control F) with a fragment of the quote to discover the cited reference. In a number of cases, I have added additional material so advanced readers, if they wish, can explore the issue in greater depth. Find can also be used to track down relevant citations, explore a topic of interest, or locate a particular section (e.g. Chapter 2 or 3.4). May I make a request? Since this Notes and References section contains over 1,300 references, it is likely that, despite my best efforts, there are still incomplete references and errors. I would appreciate readers pointing them out to me, especially since I can, in most cases, readily correct them. Thank you. Readers can email me at [email protected]. Quotes from Jim Yong Kim: On Leadership , Washington Post (April 1, 2010, listed as March 31, 2010) http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp- dyn/content/video/2010/03/31/VI2010033100606.html?hpid=smartliving CHAPTER 1 1.1 Bronislaw Malinowski, a prominent early twentieth century anthropologist, famously stated his goal in anthropology was "to grasp the native's point of view, his relation to life, to realize his vision of his world" (1961 [1922]:25) To do this, he lived as a participant-observer for roughly two years – between 1915-1918 – among the Trobriand Islanders of Papua New Guinea (in the South Pacific). Quoting him (1961[1922]:7-8): There is all the difference between a sporadic plunging into the company of natives, and being really in contact with them. -

Downloaded” to a Computer Than to Answer Questions About Emotions, Which Will Organize Their World

Between an Animal and a Machine MODERNITY IN QUESTION STUDIES IN PHILOSOPHY AND HISTORY OF IDEAS Edited by Małgorzata Kowalska VOLUME 10 Paweł Majewski Between an Animal and a Machine Stanisław Lem’s Technological Utopia Translation from Polish by Olga Kaczmarek Bibliographic Information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data is available in the internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. The Publication is founded by Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Poland as a part of the National Programme for the Development of the Humanities. This publication reflects the views only of the authors, and the Ministry cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. ISSN 2193-3421 E-ISBN 978-3-653-06830-6 (E-PDF) E-ISBN 978-3-631-71024-1 (EPUB) E-ISBN 978-3-631-71025-8 (MOBI) DOI 10.3726/978-3-653-06830-6 Open Access: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial No Derivatives 4.0 unported license. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ © Paweł Majewski, 2018 . Peter Lang – Berlin · Bern · Bruxelles · New York · Oxford · Warszawa · Wien This publication has been peer reviewed. www.peterlang.com Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................ 9 Lemology Pure and Applied ............................................................................. 9 Part One Dialogues – Cybernetics as an Anthropology ........................................ -

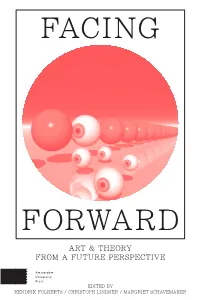

FACING FORWARD Art & Theory from a Future Perspective

This spirited exploration of the interfaces between art and theory in the 21st century brings together a range F of viewpoints on their future. Drawn from across the A fields of art history, architecture, philosophy, and media C FACING studies, the authors examine contemporary visual culture based on speculative predictions and creative scientific I arguments. Focusing on seven themes — N Future Tech G Future Image Future Museum Future City Future Freedom Future History & Future Future — the book shows how our sense of the future is shaped by a pervasive visual rhetoric of acceleration, progression, excess, and destruction. Contributors include: Hans Belting Manuel Delando Amelia Jones Rem Koolhaas China Miéville Hito Steyerl David Summers F O R W FORWARD A R ART & THEORY D FROM A FUTURE PERSPECTIVE AUP.nl 9789089647993 EDITED BY HENDRIK FOLKERTS / CHRISTOPH LINDNER / MARGRIET SCHAVEMAKER FACING FORWARD Art & Theory from a Future Perspective Edited by Hendrik Folkerts / Christoph Lindner / Margriet Schavemaker AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS COLOPHON This book is published in print and online Amsterdam University Press English- through the online OAPEN library (www. language titles are distributed in the US oapen.org). OAPEN (Open Access Publish- and Canada by the University of Chicago ing in European Networks) is a collabora- Press. tive initiative to develop and implement a sustainable Open access publication model for academic books in the Humanities and Social Sciences. The OAPEN Library aims to improve the visibility and usability of high quality academic resAearch by aggre- gating peer reviewed Open Access publica- tions from across Europe. PARTNERS ISBN Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam 978 90 8964 799 3 University of Amsterdam E-ISBN Stedelijk Museum Bureau Amsterdam 978 90 4852 623 9 (SMBA) NUR De Appel arts centre 670 W139 Metropolis M COVER DESIGN AND LAYOUT Studio Felix Salut and Stefano Faoro Creative Commons License CC BY NC (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc/3.0) All authors / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam, 2015 Some rights reserved. -

PDF Download Intercultural Communication for Global

INTERCULTURAL COMMUNICATION FOR GLOBAL ENGAGEMENT 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Regina Williams Davis | 9781465277664 | | | | | Intercultural Communication for Global Engagement 1st edition PDF Book Resilience, on the other hand, includes having an internal locus of control, persistence, tolerance for ambiguity, and resourcefulness. This textbook is suitable for the following courses: Communication and Intercultural Communication. Along with these attributes, verbal communication is also accompanied with non-verbal cues. Create lists, bibliographies and reviews: or. Linked Data More info about Linked Data. A critical analysis of intercultural communication in engineering education". Cross-cultural business communication is very helpful in building cultural intelligence through coaching and training in cross-cultural communication management and facilitation, cross-cultural negotiation, multicultural conflict resolution, customer service, business and organizational communication. September Lewis Value personal and cultural. Inquiry, as the first step of the Intercultural Praxis Model, is an overall interest in learning about and understanding individuals with different cultural backgrounds and world- views, while challenging one's own perceptions. Need assistance in supplementing your quizzes and tests? However, when the receiver of the message is a person from a different culture, the receiver uses information from his or her culture to interpret the message. Acculturation Cultural appropriation Cultural area Cultural artifact Cultural -

Introduction

M889 - FULLER TEXT.qxd 4/4/07 11:21 am Page 1 Phil's G4 Phil's G4:Users:phil:Public: PHIL'S JO Introduction Science and Technology Studies (STS) is an interdisciplinary field usually defined as the confluence of three fields with distinct intellec- tual lineages and orientations: history of science, philosophy of science, and sociology of science. All three have been marginal to their named disciplines, because surprisingly few of the original practitioners of history, philosophy, or sociology of science were primarily trained in history, philosophy, or sociology. Rather, they were natural or exact scientists who came to be disenchanted with the social entanglements of their chosen fields of study. In effect, they fell victim to an intellec- tual bait-and-switch, whereby the reasons they entered science failed to explain science’s continued support in the wider society. This point often makes STS appear more critical than many of its practitioners intend it to be. STS researchers are virtually in agreement that people tend to like science for the wrong reasons (i.e. they are too easily taken in by its hype), but relatively few STS researchers would thereby con- clude that there are no good reasons to like science. There have been three generations of STS research, and each tells a different story of disenchantment with science. First, the logical pos- itivists, including Karl Popper, were keen to protect the theoretical base of science from the technological devastation that was wrought in its name during World War I. Next, Thomas Kuhn and his con- temporaries on both sides of the Atlantic – including Paul Feyerabend, Imre Lakatos, Stephen Toulmin, Derek de Solla Price – tried to do the same vis-à-vis World War II, though, more than the previous genera- tion, they relied on science’s past for normative guidance, largely out of a realization of technology’s contemporary role in scaling up the sci- entific enterprise and giving it forward momentum. -

Gender and Sexuality

PERSPECTIVES: AN OPEN INTRODUCTION TO CULTURAL ANTHROPOLOGY SECOND EDITION Nina Brown, Thomas McIlwraith, Laura Tubelle de González 2020 American Anthropological Association 2300 Clarendon Blvd, Suite 1301 Arlington, VA 22201 ISBN Print: 978-1-931303-67-5 ISBN Digital: 978-1-931303-66-8 http://perspectives.americananthro.org/ This book is a project of the Society for Anthropology in Community Colleges (SACC) http://sacc.americananthro.org/ and our parent organization, the American Anthropological Association (AAA). Please refer to the website for a complete table of contents and more information about the book. Perspectives: An Open Introduction to Cultural Anthropology, 2nd Edition by Nina Brown, Thomas McIlwraith, Laura Tubelle de González is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted. Under this CC BY-NC 4.0 copyright license you are free to: Share — copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format Adapt — remix, transform, and build upon the material Under the following terms: Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use. NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes. 1010 GENDER AND SEXUALITY Carol C. Mukhopadhyay, San Jose State University [email protected] http://www.sjsu.edu/people/carol.mukhopadhyay Tami Blumenfield, Yunnan University [email protected] with Susan Harper, Texas Woman’s University, [email protected], and Abby Gondek, [email protected] Learning Objectives • Identify ways in which culture shapes sex/gender and sexuality. -

The Cyborg Is the Message: a Monstrous Perspective for Communication Theory Katherine Anna Merrick Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2007 The cyborg is the message: a monstrous perspective for communication theory Katherine Anna Merrick Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Other Communication Commons, and the Rhetoric and Composition Commons Recommended Citation Merrick, Katherine Anna, "The cyborg is the message: a monstrous perspective for communication theory" (2007). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 13953. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/13953 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The cyborg is the message: A monstrous perspective for communication theory by Katherine Anna Merrick A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major: Rhetoric, Composition, and Professional Communication Program of Study Committee: Don Payne, Major Professor Jean Goodwin Donna Niday Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2007 Copyright © Katherine Anna Merrick, 2007. All rights reserved. UMI Number: 1443141 UMI Microform 1443141 Copyright 2007 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform -

Crossing Cultures: Readings for Composition Pdf, Epub, Ebook

CROSSING CULTURES: READINGS FOR COMPOSITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Myrna Knepler, Annie Knepler, Ellie Knepler | 416 pages | 23 Feb 2007 | Cengage Learning, Inc | 9780618918065 | English | Belmont, CA, United States Crossing Cultures: Readings for Composition PDF Book I can see myself picking up this book to read for pleasure. The flapping flag in the painting features a circle of stars on a blue field and red and white stripes. But they are generalizations and stereotypes that have been proven to be statistically valid when applied to large populations of people over time, but to which nonetheless there are always exceptions and variations in individual and collective behavior. Sophie marked it as to- read May 22, Comparative literature Cosmopolitanism Cross-cultural leadership Cross-cultural narcissism Cross-cultural psychiatry Emotions and culture Globalism Hybridity Interculturalism Interculturality Negotiation Third culture kid Transculturation Transnationalism. Papacharissi, Zizi, ed. He created an inspirational vision of brave and upright men from a variety of backgrounds standing up and fighting together against incredible odds for the common cause of liberty. Students study select court transcripts and other primary source material from the second Scottsboro Boys Trial of , a continuation of the first trial in which two young white women wrongfully accused nine African American youths of rape. Published in , The Sound and the Fury is often referred to as William Faulkner's first work of genius. Turkle, Sherry, ed. This is the notion of distributed intelligence. Timur Sattybayev marked it as to-read Jan 17, To Kill a Mockingbird and the Scottsboro Boys Trial of Profiles in Courage Students study select court transcripts and other primary source material from the second Scottsboro Boys Trial of , a continuation of the first trial in which two young white women wrongfully accused nine African American youths of rape.