LOCATING and INTERVENING / an Introduction Gary Lee Downey and Joseph Dumit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Embracing Cyberculture on Graphic Design

Conference Proceeding: 2nd INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON CREATIVE MEDIA, DESIGN & TECHNOLOGY (REKA2016) EMBRACING CYBERCULTURE ON GRAPHIC DESIGN Nurul Hanim Romainoor 1 Universiti Sains Malaysia 1 [email protected] Sarena Abdullah 2 Universiti Sains Malaysia 2 [email protected] ABSTRACT This paper is about exploring the concept of Cyberculture on graphic design. Today, people from the different background of age and culture are engaged in using personal computers, smartphones, and even digital cameras. They are known as the active media users. They are the new inventors of graphic design, digital images, animation and films in cyberspace. This study uses a thematic lens to describe writings on popular Cyberculture. The interesting part of this section is the construction of cyberpunk and cyborg that engaged in many popular Cyberculture writings. Two lenses derived from popular Cyberculture were assessed; one is cyberpunk and two is the cyborg. These two lenses are the foundation for reviewing Cyberculture on graphic design and a reflection of graphic design involvement with the computer and the Internet are discussed. The finding on graphic design in the lens of Cyberpunk seen in design illustration of favourite comic characters. Where, active media users may transform the iconic characters into cyberpunk that portray dark colours with streaks of neon colours and lighting. While from the lens cyborg, a graphic design series can be seen in the conceptual digital art by fans illustrations that revolve around popular movies and TV series. When graphic design took notice of the cyberspace, it increased the popularity for active media users to implement a graphic design into their personal artwork. -

Part Three Autoevolution and Posthumanism

Part Three Autoevolution and Posthumanism Pawe Majewski - 9783631710258 Downloaded from PubFactory at 09/23/2021 08:08:01PM via free access Pawe Majewski - 9783631710258 Downloaded from PubFactory at 09/23/2021 08:08:01PM via free access 17 Themes of Lampoon of Evolution In Part Three of this book I will discuss the last chapter of ST, and then some of the currents in contemporary philosophy and sociology, which in one way or another seem to be akin to Lem’s project of autoevolution. These are mostly convergences rather than any kind of genetic affinities, and will partly be constructed through my interpretations. The aim is to show that Lem’s work, especially ST, has great albeit so far unacknowledged significance for the con- temporary problems of our civilization. The last chapter of ST is titled “Lampoon of Evolution.” It includes a descrip- tion of the project of autoevolution of human species, the very description to which the rest of ST is but a set of introductory studies, as I have suggested ear- lier. The word “lampoon” ought to be taken with a grain of salt, just as other rhetorical devices Lem uses in the titles of his chapters and sections of ST. It is a testimony to Lem’s personal and internally diverse attitude to bioevolution. He both admires the phenomenon, which he often hypostatizes, and is critical and hostile to it. The admiration comes from the fact that bioevolution has pro- duced such amazing beings as a biological cell and rational humans.180 The crit- icism and hostility stem from the fact that for Lem the rationalist the process is unbearable in how blindly random it is. -

Downloaded” to a Computer Than to Answer Questions About Emotions, Which Will Organize Their World

Between an Animal and a Machine MODERNITY IN QUESTION STUDIES IN PHILOSOPHY AND HISTORY OF IDEAS Edited by Małgorzata Kowalska VOLUME 10 Paweł Majewski Between an Animal and a Machine Stanisław Lem’s Technological Utopia Translation from Polish by Olga Kaczmarek Bibliographic Information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data is available in the internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. The Publication is founded by Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Poland as a part of the National Programme for the Development of the Humanities. This publication reflects the views only of the authors, and the Ministry cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. ISSN 2193-3421 E-ISBN 978-3-653-06830-6 (E-PDF) E-ISBN 978-3-631-71024-1 (EPUB) E-ISBN 978-3-631-71025-8 (MOBI) DOI 10.3726/978-3-653-06830-6 Open Access: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial No Derivatives 4.0 unported license. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ © Paweł Majewski, 2018 . Peter Lang – Berlin · Bern · Bruxelles · New York · Oxford · Warszawa · Wien This publication has been peer reviewed. www.peterlang.com Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................ 9 Lemology Pure and Applied ............................................................................. 9 Part One Dialogues – Cybernetics as an Anthropology ........................................ -

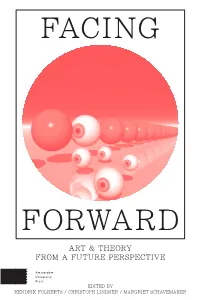

FACING FORWARD Art & Theory from a Future Perspective

This spirited exploration of the interfaces between art and theory in the 21st century brings together a range F of viewpoints on their future. Drawn from across the A fields of art history, architecture, philosophy, and media C FACING studies, the authors examine contemporary visual culture based on speculative predictions and creative scientific I arguments. Focusing on seven themes — N Future Tech G Future Image Future Museum Future City Future Freedom Future History & Future Future — the book shows how our sense of the future is shaped by a pervasive visual rhetoric of acceleration, progression, excess, and destruction. Contributors include: Hans Belting Manuel Delando Amelia Jones Rem Koolhaas China Miéville Hito Steyerl David Summers F O R W FORWARD A R ART & THEORY D FROM A FUTURE PERSPECTIVE AUP.nl 9789089647993 EDITED BY HENDRIK FOLKERTS / CHRISTOPH LINDNER / MARGRIET SCHAVEMAKER FACING FORWARD Art & Theory from a Future Perspective Edited by Hendrik Folkerts / Christoph Lindner / Margriet Schavemaker AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS COLOPHON This book is published in print and online Amsterdam University Press English- through the online OAPEN library (www. language titles are distributed in the US oapen.org). OAPEN (Open Access Publish- and Canada by the University of Chicago ing in European Networks) is a collabora- Press. tive initiative to develop and implement a sustainable Open access publication model for academic books in the Humanities and Social Sciences. The OAPEN Library aims to improve the visibility and usability of high quality academic resAearch by aggre- gating peer reviewed Open Access publica- tions from across Europe. PARTNERS ISBN Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam 978 90 8964 799 3 University of Amsterdam E-ISBN Stedelijk Museum Bureau Amsterdam 978 90 4852 623 9 (SMBA) NUR De Appel arts centre 670 W139 Metropolis M COVER DESIGN AND LAYOUT Studio Felix Salut and Stefano Faoro Creative Commons License CC BY NC (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc/3.0) All authors / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam, 2015 Some rights reserved. -

Introduction

M889 - FULLER TEXT.qxd 4/4/07 11:21 am Page 1 Phil's G4 Phil's G4:Users:phil:Public: PHIL'S JO Introduction Science and Technology Studies (STS) is an interdisciplinary field usually defined as the confluence of three fields with distinct intellec- tual lineages and orientations: history of science, philosophy of science, and sociology of science. All three have been marginal to their named disciplines, because surprisingly few of the original practitioners of history, philosophy, or sociology of science were primarily trained in history, philosophy, or sociology. Rather, they were natural or exact scientists who came to be disenchanted with the social entanglements of their chosen fields of study. In effect, they fell victim to an intellec- tual bait-and-switch, whereby the reasons they entered science failed to explain science’s continued support in the wider society. This point often makes STS appear more critical than many of its practitioners intend it to be. STS researchers are virtually in agreement that people tend to like science for the wrong reasons (i.e. they are too easily taken in by its hype), but relatively few STS researchers would thereby con- clude that there are no good reasons to like science. There have been three generations of STS research, and each tells a different story of disenchantment with science. First, the logical pos- itivists, including Karl Popper, were keen to protect the theoretical base of science from the technological devastation that was wrought in its name during World War I. Next, Thomas Kuhn and his con- temporaries on both sides of the Atlantic – including Paul Feyerabend, Imre Lakatos, Stephen Toulmin, Derek de Solla Price – tried to do the same vis-à-vis World War II, though, more than the previous genera- tion, they relied on science’s past for normative guidance, largely out of a realization of technology’s contemporary role in scaling up the sci- entific enterprise and giving it forward momentum. -

The Cyborg Is the Message: a Monstrous Perspective for Communication Theory Katherine Anna Merrick Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2007 The cyborg is the message: a monstrous perspective for communication theory Katherine Anna Merrick Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Other Communication Commons, and the Rhetoric and Composition Commons Recommended Citation Merrick, Katherine Anna, "The cyborg is the message: a monstrous perspective for communication theory" (2007). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 13953. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/13953 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The cyborg is the message: A monstrous perspective for communication theory by Katherine Anna Merrick A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major: Rhetoric, Composition, and Professional Communication Program of Study Committee: Don Payne, Major Professor Jean Goodwin Donna Niday Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2007 Copyright © Katherine Anna Merrick, 2007. All rights reserved. UMI Number: 1443141 UMI Microform 1443141 Copyright 2007 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform -

Effects of Human-Machine Integration on the Construction of Identity

Effects of human-machine integration on the construction of identity Francesc Ballesté (Humanitats, UOC, Barcelona) Carme Torras (Institut de Robòtica i Informàtica Industrial, CSIC-UPC, Barcelona) Abstract Recent developments in social robotics, intelligent prosthetics, brain-computer interfaces and implants pose new questions as to the effects of technology on identity, society and the future of humankind. Our standpoint is that such effects cannot be studied separately from their social/cultural context, and thus we begin by reviewing the existing approaches to the social construction of reality, placing special emphasis on language and its limitations to describe the future. Then, we focus on the body as the place where the human-machine integration occurs, and we describe four levels at which the notion of cyborg has been analyzed in anthropological studies: symbolic, physical, as a permeable layer between nature and culture, and as an intermediate step towards a higher-order existence. We end up with a word of caution in relation to technological determinism stemming from STS (Science and Technology Studies), as well as the need to establish Relevant Social Groups (RSG) with well-founded criteria that join scientific and sociological academics under a multidisciplinary approach. 1. Introduction 1 Our aim is to study the basic factors to be considered when exploring the effects of technology on identity and its impact on society. We see that there are three such factors. First, we follow the thesis of Ihde (2004) regarding technological 'multi-stability' in that predicting the effects of a new technology is difficult because of the appearance of unforeseen uses for it. -

Four Genealogies for a Recombinant Anthropology of Science and Technology

FOUR GENEALOGIES FOR A RECOMBINANT ANTHROPOLOGY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY MICHAEL M. J. FISCHER CMassachusettsA Institute of Technology INTRODUCTORY OVERTURE The call of and for an Anthropology of Science and Technology requires a new generation of robust switches to translate legacy genealogies to public futures.1 Just as we have moved from Mertonian sociologies of science (stressing the regulative ideals of organized skepticism, disinterested objectivity, universalism, and commu- nal ownership of ideas) to analyses of what scientists actually do (the slogans of the “new sociologies of science,” i.e., social studies of knowledge (SSK), and “social construction” of technology [SCOT], and of the anthropologically informed ethno- graphies of science and technology of the 1990s), so too we need now to formulate anthropologies of science and technology that attend to both the cultural switches of the heterogeneous communities within which sciences are cultured and tech- nologies are peopled, and to the reflexive social institutions within which medical, environmental, informational, and other technosciences must increasingly operate. Public futures are playing out in culturally and socially contested sites around the world where knowledges are generated and infrastructures are assembled, empowering some and disempowering others, calling for effective engagement across cultural difference. These public futures can be seen emerging in today’s sciences of climate change and biodiversity built on knowledge of the Amazon, Indonesia, or the environment of circumpolar populations (Callison 2007; Lahsen 2001, 2004, 2005; Lowe 2006; Tsing 2005); in the way knowledge of the risks of CULTURAL ANTHROPOLOGY, Vol. 22, Issue 4, pp. 539–615. ISSN 0886-7356, online ISSN 1548-1360. -

Redalyc.RACE AS TECHNOLOGY: from POSTHUMAN CYBORG TO

Ilha do Desterro: A Journal of English Language, Literatures in English and Cultural Studies E-ISSN: 2175-8026 [email protected] Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina Brasil Jones, Holly; Jones, Nicholaos RACE AS TECHNOLOGY: FROM POSTHUMAN CYBORG TO HUMAN INDUSTRY Ilha do Desterro: A Journal of English Language, Literatures in English and Cultural Studies, vol. 70, núm. 2, mayo-agosto, 2017, pp. 39-51 Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina Florianópolis, Brasil Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=478355303004 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5007/2175-8026.2017v70n2p39 RACE AS TECHNOLOGY: FROM POSTHUMAN CYBORG TO HUMAN INDUSTRY Holly Jones* he University of Alabama in Huntsville Huntsville, USA. Nicholaos Jones** he University of Alabama in Huntsville Huntsville, USA. Abstract Cyborg and prosthetic technologies frame prominent posthumanist approaches to understanding the nature of race. But these frameworks struggle to accommodate the phenomena of racial passing and racial stationarity, and their posthumanist orientation blurs useful distinctions between racialized humans and their social contexts. We advocate, instead, a humanist approach to race, understanding racial hierarchy as an industrial technology. Our approach accommodates racial passing and stationarity. It integrates a wide array of research across disciplines. It also helpfully distinguishes among the grounds of racialization and conditions facilitating the impacts of such racialization. Keywords: Eyeborg; Haraway; industrial technology; humanism; racial hierarchy 1 Introductory Remarks within a racial hierarchy. -

From Cyber to Digital Anthropology to an Anthropology of the Contemporary Philipp Budka (University of Vienna)

From Cyber to Digital Anthropology to an Anthropology of the Contemporary Philipp Budka (University of Vienna) www.philbu.net Paper at the DGV (German Anthropological Association) Workshop “Cyberculture” 15 September 2011, University of Vienna Introduction This paper is first taking a brief look back on the “anthropology of cyberculture”, formulated as anthropological research area, concept and issue by Arturo Escobar in 1994. Inspired by science and technology studies, he painted a very vivid picture how anthropology and ethnography could contribute to the understanding of new bio and communication technologies as society's transforming driving forces. Pushed by powerful digital media technologies, such as internet applications and services, a “digital anthropology” recently developed, particularly under the influence of material culture theory. What is the legacy of the anthropology of cyberculture when dealing with new digital practices? And is it actually necessary to construct branches of anthropology that deal with contemporary sociocultural developments? Or should we just open the discipline to an “anthropology of the contemporary”, as Rabinow and Marcus (2008) propose. Cyber anthropology – the anthropology of cyberculture The term “cyberanthropology” derives from the notion of “cyberspace”, which was for the first time mentioned in the science fiction novel Neuromancer by William Gibson in 1984. The prefix “cyber” was established by the mathematician Norbert Wiener at the end of the 1940s by using the notion “cybernetics” to describe the science of human-machine interaction. Wiener had in mind the Greek word for “steersman” or “pilot” – kybernetes – to describe a steering or controlling device for machines. It was after the Second World War and at the beginning of the Cold War when cybernetics as discipline was established and popularized, mainly by the work of Wiener (1948). -

Social Studies of Science

Social Studies of Science http://sss.sagepub.com/ Where are the Cyborgs in Cybernetics? Ronald Kline Social Studies of Science 2009 39: 331 DOI: 10.1177/0306312708101046 The online version of this article can be found at: http://sss.sagepub.com/content/39/3/331 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com Additional services and information for Social Studies of Science can be found at: Email Alerts: http://sss.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://sss.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Citations: http://sss.sagepub.com/content/39/3/331.refs.html >> Version of Record - May 22, 2009 What is This? Downloaded from sss.sagepub.com at St Petersburg State University on January 11, 2014 ABSTRACT Cyborgs – cybernetic organisms, hybrids of humans and machines – have pervaded everyday life, the military, popular culture, and the academic world since the advent of cyborg studies in the mid 1980s. They have been a recurrent theme in STS in recent decades, but there are surprisingly few cyborgs referred to in the early history of cybernetics in the USA and Britain. In this paper, I analyze the work of the early cyberneticians who researched and built cyborgs. I then use that history of cyborgs as a basis for reinterpreting the history of cybernetics by critiquing cyborg studies that give a teleological account of cybernetics, and histories of cybernetics that view it as a unitary discipline. I argue that cyborgs were a minor research area in cybernetics, usually classified under the heading of ‘medical cybernetics’, in the USA and Britain from the publication of Wiener’s Cybernetics in 1948 to the decline of cybernetics among mainstream scientists in the 1960s. -

ANTHGM01: Core Course in Digital Anthropology: Hannah Knox and Haidy Geismar | University College London

09/25/21 ANTHGM01: Core Course in Digital Anthropology: Hannah Knox and Haidy Geismar | University College London ANTHGM01: Core Course in Digital View Online Anthropology: Hannah Knox and Haidy Geismar Post Graduate Core Course in Digital Anthropology Hannah Knox and Haidy Geismar abanovi , S. ‘Inventing Japan’s “Robotics Culture”: The Repeated Assembly of Science, Technology, and Culture in Social Robotics’. Social Studies of Science 44.3 (2014): 342–367. Web. ‘A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace.’ N.p., n.d. Web. <https://homes.eff.org/~barlow/Declaration-Final.html>. ---. N.p., n.d. Web. <https://homes.eff.org/~barlow/Declaration-Final.html>. Akrich, Madeleine. ‘The De-Scription of Technical Objects.’ Shaping Technology/building Society : Studies in Sociotechnical Change / Edited by Wiebe E. Bijker and John Law. N.p., 1992. Web. <http://ucl-primo.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/primo_library/libweb/action/display.do?tabs=de tailsTab&ct=display&fn=search&doc=dedupmrg114643604&indx=1&recIds=dedupmrg11 4643604&recIdxs=0&elementId=0&renderMode=poppedOut&displayMode=full&frbrVersi on=&dscnt=0&frbg=&scp.scps=scope%3A%28UCL_LMS_DS%29&tab=local&dstmp=1415 788466910&srt=rank&mode=Basic&&dum=true&tb=t&vl(freeText0)=Shaping%20Techno logy%2FBuilding%20Society&vid=UCL_VU1>. Andrea Ballestero. ‘What’s in a Percentage? Calculation as the Poetic Translation of Human Rights.’ 21.1 (2014): 27–53. Web. <http://www.jstor.org/discover/10.2979/indjglolegstu.21.1.27?uid=3738032&uid=2&uid=4 &sid=21104585708101>. Annelise Riles. ‘Infinity within the Brackets.’ 25.3 (1998): 378–398. Web. <http://www.jstor.org/discover/10.2307/645790?uid=3738032&uid=2&uid=4&sid=211045 85708101>.