Part Three Autoevolution and Posthumanism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MASKA STANISŁAWA LEMA Opowiadanie Maska S

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS LODZIENSIS FOLIA LITTERARIA POLONICA 9, 2007 Maciej Wróblewski CZY MASZYNA MOŻE BYĆ CZŁOWIEKIEM? M A SK A STANISŁAWA LEMA Lalka woskowa jest imitacją człowieka, nieprawdaż? A jeżeli ktoś sporządzi lalkę, która będzie chodziła i mówiła, będzie to imitacja wyborna. A jeśli skon- struuje lalkę krwawiącą? Lalkę, która będzie nie- szczęśliwa i śmiertelna, co wtedy?1 Opowiadanie M aska Stanisława Lema zaliczyć można, nie narażając się na błąd subiektywizmu, do tekstów udanych literacko i intrygujących myś- lowo. Obydwa poziomy - estetyczny i intelektualny - wzajemnie się warun- kują i stanowią o wartości utworu, który w odbiorze jest niełatwy i wielo- wykładalny. W wywiadzie-rzece, przeprowadzonym przez Stanisława Beresia, w następujący sposób Lem opowiadał o swojej strategii pisarskiej: „Ogólnie mówiąc, im bardziej utwór jest oryginalny, czyli odstrychnięty od wzorca gatunkowego, tym bardziej wielowykładalny jak test Rorschacha. Ale oczy- wiście nie mogę siadać do maszyny z postanowieniem napisania «bardzo oryginalnego i przez to wielowykładalnego tekstu»”2. Każde dzieło artystyczne, jak wiadomo, niesie w sobie pewien naddatek, pozwalający spostrzec je jako byt odrębny, nie-rzeczywisty (choć z rzeczywis- tości biorący swój początek), a M aska Lema zdaje się literacką i myślową zagadką, czymś ex definitione niejednoznacznym, chociaż artystycznie (kom- pozycyjnie) wyrazistym i kompletnym w tym sensie, że autor zrezygnował z eksperymentu formalnego: na poziomie narracji, prezentacji postaci czy kompozycji. Opowiadanie manifestuje swoją dziwność i tajemniczość w spo- sób bezdyskusyjny, ale odmienny niż robią to autorzy tekstów science fiction , np. poprzez nagromadzenie rekwizytów, opisy zjawisk kosmicznych i od- ległych od Ziemi planet wraz z zamieszkującymi je cywilizacjami. Dodajmy jednak, iż Masce nie można odmówić cech, pozwalających umieścić ją 1 S. -

Politics and Metaphysics in Three Novels of Philip K. Dick

EUGÊNIA BARTHELMESS Politics and Metaphysics in Three Novels of Philip K. Dick Dissertação apresentada ao Curso de Pós- Graduação em Letras, Área de Concentra- ção Literaturas de Língua Inglesa, do Setor de Ciências Humanas, Letras e Artes da Universidade Federai do Paraná, como requisito parcial à obtenção do grau de Mestre. Orientadora: Prof.3 Dr.a BRUNILDA REICHMAN LEMOS CURITIBA 19 8 7 OF PHILIP K. DICK ERRATA FOR READ p -;2011 '6:€h|j'column iinesllll^^is'iiearly jfifties (e'jarly i fx|fties') fifties); Jl ' 1 p,.2Ò 6th' column line 16 space race space race (late fifties) p . 33 line 13 1889 1899 i -,;r „ i i ii 31 p .38 line 4 reel."31 reel • p.41 line 21 ninteenth nineteenth p .6 4 line 6 acien ce science p .6 9 line 6 tear tears p. 70 line 21 ' miliion million p .72 line 5 innocence experience p.93 line 24 ROBINSON Robinson p. 9 3 line 26 Robinson ROBINSON! :; 1 i ;.!'M l1 ! ! t i " i î : '1 I fi ' ! • 1 p .9 3 line 27 as deliberate as a deliberate jf ! •! : ji ' i' ! p .96 lin;e , 5! . 1 from form ! ! 1' ' p. 96 line 8 male dis tory maledictory I p .115 line 27 cookedly crookedly / f1 • ' ' p.151 line 32 why this is ' why is this I 1; - . p.151 line 33 Because it'll Because (....) it'll p.189 line 15 mourmtain mountain 1 | p .225 line 13 crete create p.232 line 27 Massachusetts, 1960. Massachusetts, M. I. T. -

The Palgrave Handbook of Posthumanism in Film and Television the Palgrave Handbook of Posthumanism in Film and Television

The Palgrave Handbook of Posthumanism in Film and Television The Palgrave Handbook of Posthumanism in Film and Television Edited by Michael Hauskeller University of Exeter, UK Thomas D. Philbeck World Economic Forum, Switzerland Curtis D. Carbonell Khalifa University of Science, Technology and Research, UAE Selection and editorial matter © Michael Hauskeller, Thomas D. Philbeck and Curtis D. Carbonell 2015 Individual chapters © Respective authors 2015 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 2015 978-1-137-43031-1 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, Saffron House, 6–10 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The authors have asserted their rights to be identified as the authors of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2015 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Palgrave Macmillan in the UK is an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS. Palgrave Macmillan in the US is a division of St Martin’s Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010. Palgrave Macmillan is the global academic imprint of the above companies and has companies and representatives throughout the world. -

Embracing Cyberculture on Graphic Design

Conference Proceeding: 2nd INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON CREATIVE MEDIA, DESIGN & TECHNOLOGY (REKA2016) EMBRACING CYBERCULTURE ON GRAPHIC DESIGN Nurul Hanim Romainoor 1 Universiti Sains Malaysia 1 [email protected] Sarena Abdullah 2 Universiti Sains Malaysia 2 [email protected] ABSTRACT This paper is about exploring the concept of Cyberculture on graphic design. Today, people from the different background of age and culture are engaged in using personal computers, smartphones, and even digital cameras. They are known as the active media users. They are the new inventors of graphic design, digital images, animation and films in cyberspace. This study uses a thematic lens to describe writings on popular Cyberculture. The interesting part of this section is the construction of cyberpunk and cyborg that engaged in many popular Cyberculture writings. Two lenses derived from popular Cyberculture were assessed; one is cyberpunk and two is the cyborg. These two lenses are the foundation for reviewing Cyberculture on graphic design and a reflection of graphic design involvement with the computer and the Internet are discussed. The finding on graphic design in the lens of Cyberpunk seen in design illustration of favourite comic characters. Where, active media users may transform the iconic characters into cyberpunk that portray dark colours with streaks of neon colours and lighting. While from the lens cyborg, a graphic design series can be seen in the conceptual digital art by fans illustrations that revolve around popular movies and TV series. When graphic design took notice of the cyberspace, it increased the popularity for active media users to implement a graphic design into their personal artwork. -

Teaching the Short Story: a Guide to Using Stories from Around the World. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 397 453 CS 215 435 AUTHOR Neumann, Bonnie H., Ed.; McDonnell, Helen M., Ed. TITLE Teaching the Short Story: A Guide to Using Stories from around the World. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-1947-6 PUB DATE 96 NOTE 311p. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock No. 19476: $15.95 members, $21.95 nonmembers). PUB 'TYPE Guides Classroom Use Teaching Guides (For Teacher) (052) Collected Works General (020) Books (010) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC13 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Authors; Higher Education; High Schools; *Literary Criticism; Literary Devices; *Literature Appreciation; Multicultural Education; *Short Stories; *World Literature IDENTIFIERS *Comparative Literature; *Literature in Translation; Response to Literature ABSTRACT An innovative and practical resource for teachers looking to move beyond English and American works, this book explores 175 highly teachable short stories from nearly 50 countries, highlighting the work of recognized authors from practically every continent, authors such as Chinua Achebe, Anita Desai, Nadine Gordimer, Milan Kundera, Isak Dinesen, Octavio Paz, Jorge Amado, and Yukio Mishima. The stories in the book were selected and annotated by experienced teachers, and include information about the author, a synopsis of the story, and comparisons to frequently anthologized stories and readily available literary and artistic works. Also provided are six practical indexes, including those'that help teachers select short stories by title, country of origin, English-languag- source, comparison by themes, or comparison by literary devices. The final index, the cross-reference index, summarizes all the comparative material cited within the book,with the titles of annotated books appearing in capital letters. -

Japońska Polska. Kulturowy Wizerunek Polski W Japonii

Artykuły IV. Varia Zeszyty Naukowe KUL 60 (2018), nr 2 (242) R YSZARD Z A JąC ZKOWSK I* Japońska Polska. Kulturowy wizerunek Polski w Japonii aponia nie jest w Polsce krajem nieznanym1. Recepcja jej kultury zaczęła się Jna Wisłą na początku XX w., kiedy też zapanowała moda na japońszczyznę. Zupełnie inna kwestia to obecność kultury polskiej na wyspach japońskich2. Na ten temat wiemy niewiele. Pytanie o wizerunek naszego kraju w Japonii – zwłaszcza w wymiarze kulturowym do którego się ograniczę – ma znaczenie w globalizującym się świecie i pozwala z innej perspektywy spojrzeć na Polskę. Kultura – jak dowiodła tego historia – to ważny czynnik służący zbliżeniu między oboma krajami. Japończykom znacznie bliżej jest do Chin, do Korei czy do Rosji. Z naturalnych względów interesuje ich też obszar anglosaski. Europę (zwłaszcza Niemcy, Anglię i Francję) traktują jako ciekawy cel wojaży turystycz- nych bądź studiów. Wciąż jednak niezbyt często trafiają do Polski (choć liczba turystów stale rośnie!). Mimo to kultura polska obecna jest w Japonii w różnej postaci, zwłaszcza z chwilą wejścia Polski do Unii Europejskiej, która na różny sposób promuje tu swoje osiągnięcia i wizerunek. Zacznijmy od literatury, z tym jednak zastrzeżeniem, że nie ma dotych- czas satysfakcjonujących zestawień bibliograficznych obrazujących recepcję polskiej sztuki słowa w Japonii. Z tej racji można pokusić się tylko o wstępne * Dr hab. Ryszard Zajączkowski, prof. KUL – Katedra Teorii Kultury i Sztuki KUL; e-mail: [email protected]. 1 Artykuł został opracowany w ramach stażu „Najlepsze praktyki” w strategicznej transformacji KUL w Tokyo University of Foreign Studies w 2015 r. 2 Godną polecenia pracą jest książka Historia stosunków polsko-japońskich 1904-1945 pod. -

Downloaded” to a Computer Than to Answer Questions About Emotions, Which Will Organize Their World

Between an Animal and a Machine MODERNITY IN QUESTION STUDIES IN PHILOSOPHY AND HISTORY OF IDEAS Edited by Małgorzata Kowalska VOLUME 10 Paweł Majewski Between an Animal and a Machine Stanisław Lem’s Technological Utopia Translation from Polish by Olga Kaczmarek Bibliographic Information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data is available in the internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. The Publication is founded by Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Poland as a part of the National Programme for the Development of the Humanities. This publication reflects the views only of the authors, and the Ministry cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. ISSN 2193-3421 E-ISBN 978-3-653-06830-6 (E-PDF) E-ISBN 978-3-631-71024-1 (EPUB) E-ISBN 978-3-631-71025-8 (MOBI) DOI 10.3726/978-3-653-06830-6 Open Access: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial No Derivatives 4.0 unported license. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ © Paweł Majewski, 2018 . Peter Lang – Berlin · Bern · Bruxelles · New York · Oxford · Warszawa · Wien This publication has been peer reviewed. www.peterlang.com Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................ 9 Lemology Pure and Applied ............................................................................. 9 Part One Dialogues – Cybernetics as an Anthropology ........................................ -

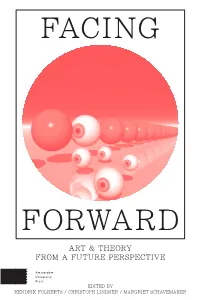

FACING FORWARD Art & Theory from a Future Perspective

This spirited exploration of the interfaces between art and theory in the 21st century brings together a range F of viewpoints on their future. Drawn from across the A fields of art history, architecture, philosophy, and media C FACING studies, the authors examine contemporary visual culture based on speculative predictions and creative scientific I arguments. Focusing on seven themes — N Future Tech G Future Image Future Museum Future City Future Freedom Future History & Future Future — the book shows how our sense of the future is shaped by a pervasive visual rhetoric of acceleration, progression, excess, and destruction. Contributors include: Hans Belting Manuel Delando Amelia Jones Rem Koolhaas China Miéville Hito Steyerl David Summers F O R W FORWARD A R ART & THEORY D FROM A FUTURE PERSPECTIVE AUP.nl 9789089647993 EDITED BY HENDRIK FOLKERTS / CHRISTOPH LINDNER / MARGRIET SCHAVEMAKER FACING FORWARD Art & Theory from a Future Perspective Edited by Hendrik Folkerts / Christoph Lindner / Margriet Schavemaker AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS COLOPHON This book is published in print and online Amsterdam University Press English- through the online OAPEN library (www. language titles are distributed in the US oapen.org). OAPEN (Open Access Publish- and Canada by the University of Chicago ing in European Networks) is a collabora- Press. tive initiative to develop and implement a sustainable Open access publication model for academic books in the Humanities and Social Sciences. The OAPEN Library aims to improve the visibility and usability of high quality academic resAearch by aggre- gating peer reviewed Open Access publica- tions from across Europe. PARTNERS ISBN Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam 978 90 8964 799 3 University of Amsterdam E-ISBN Stedelijk Museum Bureau Amsterdam 978 90 4852 623 9 (SMBA) NUR De Appel arts centre 670 W139 Metropolis M COVER DESIGN AND LAYOUT Studio Felix Salut and Stefano Faoro Creative Commons License CC BY NC (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc/3.0) All authors / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam, 2015 Some rights reserved. -

Solaris Across Media. Mark Bould. Solaris. BFI Film Classics

Reviews of Books 113 Emerging from Its Elements: Solaris across Media. Mark Bould. Solaris. BFI Film Classics. Palgrave McMillan: London, 2014. 96 pp. ISBN: 978-1-84- 457805-4. $17.95 pbk. Reviewed by Melody Jue When you walk into an aquarium, you are usually greeted by signs that welcome you to the “alien” realm of the ocean, with its “extraterrestrial” creatures, like the octopus and nautilus. One of the curious things about the ocean planet Solaris—as imagined by Stanislaw Lem and Andrei Tarkovsky—is that it has no indigenous life forms. In both Lem’s 1961 novel and Tarkovsky’s 1972 film, the planet Solaris is one massive ocean body of transient sculptural formations, perhaps sentient on a scale beyond human comprehension. The planet is at once an environment and a subject, presenting particular challenges for thinking about cinematic perception and the genre of sf. Mark Bould’s study of Tarkovsky’s Solaris is a new contribution to BFI’s Film Classics series that engages with the interrelation of environment and subjectivity. Although the book is organized into three chapters (“Sf, Tarkovsky and Lem,” “Solarises,” and “Tarkovsky’s Solaris”), the last chapter on Tarkovsky’s film comprises the majority of the book. Bould carefully recounts the plot of the film, occasionally splicing in forays into production history, literary and cinematic precedents, and full-color film frames. Bould’s Solaris is, in many ways, not simply a study of Tarkovsky’s Solaris, but an additional remediation of the film and novel that stands on its own. What emerges from Bould’s prudent analysis is an environmental sensibility: that the key to interpreting Solaris lies in a cinematic grammar that emerges out of its natural elements. -

Beyond Humanism: Reflections on Trans- and Posthumanism

A peer-reviewed electronic journal published by the Institute for Ethics and Emerging Technologies ISSN 1541-0099 21(2) – October 2010 Beyond Humanism: Reflections on Trans- and Posthumanism Stefan Lorenz Sorgner Department of Philosophy University of Erfurt, Germany [email protected] Journal of Evolution and Technology - Vol. 21 Issue 2 – October 2010 - pgs 1-19 http://jetpress.org/sorgner.htm Abstract I am focusing here on the main counterarguments that were raised against a thesis I put forward in my article “Nietzsche, the Overhuman, and Transhumanism” (2009), namely that significant similarities can be found on a fundamental level between the concept of the posthuman, as put forward by some transhumanists, and Nietzsche’s concept of the overhuman. The articles with the counterarguments were published in the recent “Nietzsche and European Posthumanisms” issue of The Journal of Evolution and Technology (January-July 2010). As several commentators referred to identical issues, I decided that it would be appropriate not to respond to each of the articles individually, but to focus on the central arguments and to deal with the counterarguments mentioned in the various replies. I am concerned with each topic in a separate section. The sections are entitled as follows: 1. Technology and evolution; 2. Overcoming nihilism; 3. Politics and liberalism; 4. Utilitarianism or virtue ethics?; 5. The good Life; 6. Creativity and the will to power; 7. Immortality and longevity; 8. Logocentrism; 9. The Third Reich. When dealing with the various topics, I am not merely responding to counterarguments; I also raise questions concerning transhumanism and put forward my own views concerning some of the questions I am dealing with. -

Rereading Posthumanism in the War of the Worlds and Independence Day

eSharp Issue 12: Technology and Humanity Rereading Posthumanism in The War of the Worlds and Independence Day Alistair Brown (Durham University) Science Fiction as the Discovery of the Future In a 1902 presentation to the Royal Institution on ‘The Discovery of the Future,’ H.G. Wells contrasted two types of mind: the legal or submissive type, and the creative or legislative. 1 The former, which predominates in society, is retrospective, fatalistically understanding the present in terms of precedent. The more modern, creative type ‘sees the world as one great workshop, and the present no more than material for the future’ (Wells 1989, p.19) and is implicitly associated with the writer of science fiction (or the scientific romance, as then known). Given our acquaintance with Wells’ descendents like Isaac Asimov or Arthur C. Clarke, this seems fairly uncontentious. However, in a climate of postmodern relativism we may be less comfortable with the way in which Wells went on to formalise the relationship between present and future. He compared the creative predictions of the future to those analyses of distant prehistory made by the relatively recent sciences of geology and archaeology, and contended that it ought to be possible to produce a long term portrait of the future as has been done with the ancient ‘inductive past’ (1989, p.27). Though many prominent science fiction writers assert that science fiction is the reasonable extrapolation of present 1 A shorter version of this paper was presented to the British Society of Literature and Science conference in Keele in March 2008. I am grateful for all the comments received there, in response to which some parts of this paper have been modified. -

The Potential of Posthumanism: Reimagining Utopia Through

THE POTENTIAL OF POSTHUMANISM: REIMAGINING UTOPIA THROUGH BELLAMY, ATWOOD, AND SLONCZEWSKI by JACOB MCKEEVER Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Arlington in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN ENGLISH THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON December 2014 Copyright © by Jacob McKeever 2014 All Rights Reserved ii Acknowledgements Though on the surface it was the smallest of gestures, this journey could not have begun without Dr. Kevin Gustafson, graduate advisor of English at the time, whose course suggestions helped this once ignorant anthropology major turned hopeful English graduate student begin this path. To Dr. Kenneth Roemer, thesis chair and director, thank you immensely for your insightful comments and guidance throughout this process. Not only were you the ideal committee chair, you were a constant figure of optimism throughout my time in the English program. To Dr. Stacy Alaimo and Dr. Timothy Richardson, committee members, my greatest appreciation goes out for your initial willingness to be a part of this committee and your eventual patience during the final stages. I sincerely appreciate all of you for your roles in both this process and my successful completion of this program. Most importantly, I want to acknowledge my family as my main inspiration and motivation. To Ashley, for subjecting yourself to my endless drafts and for your unending patience every day. And to Alec and Zoe, whose dad can finally come out and play. November 19, 2014 iii Abstract THE POTENTIAL OF POSTHUMANISM: REIMAGINING UTOPIA THROUGH BELLAMY, ATWOOD, AND SLONCZEWSKI Jacob McKeever, M.A.