Because Maps Used to Say “There Be Dragons Here”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stijl in Fargo

BACHELOR EINDWERKSTUK Jasper Koenen 3909700 Media- en Cultuurwetenschappen Docent: Hanna Surma Studiejaar 2015-2016, blok 2. Inleverdatum: 29 januari 2016 STIJL IN FARGO Stilistische analyse naar de functie van stijl op de vormgeving van het personage Gus Grimly. Deze pagina is welbewust wit gelaten. 1 Abstract In dit eindwerkstuk wordt er onderzoek gedaan naar de relatie tussen stijl en personage in dramaserie FARGO van FX. Het personage dat centraal zal staat is Gus Grimly. Er is gekozen voor dit personage vanwege de grote ontwikkeling die hij doormaakt. Met behulp van een stilistische analyse worden de stijlelementen mise-en-scène, geluid en montage nader bekeken. De opzet van de analyse is overgenomen van mediawetenschapper Jeremy Butler. In zijn boek TV Style werkt hij een methode uit voor onderzoek naar stijl in televisie. Uit de analyse die is uitgevoerd in dit eindwerkstuk blijkt stijl een belangrijke functie te hebben. Waar Gus zich na tien afleveringen ontpopt tot personage dat in staat is iemand te vermoorden, lijkt stijl juist iets anders te willen betogen. Gus wordt immer afgebeeld als de rustige en goedaardige man en zelfs na het doden van Lorne Malvo blijft de vormgeving onveranderd. Hiermee wordt aangegeven dat Gus als personage niet veranderd is, maar dat het doden van Lorne een actie was waar Gus dwangmatig aan toe moest geven. Stijl is dus in staat een boodschap uit te dragen die in eerste instantie niet lijkt te stroken met wat het narratief van een serie vertelt. Keywords: Television Style; stylistic analysis, complex tv, character development. 2 Inhoudsopgave Abstract ................................................................................................................................................... 2 1. Inleiding .......................................................................................................................................... -

Masterarbeit / Master's Thesis

MASTERARBEIT / MASTER’S THESIS Titel der Masterarbeit / Title of the Master‘s Thesis „Eat the Rude. Serielle Verfahren und die Ästhetisierung kannibalistischer Gewalt in der TV-Serie Hannibal“ verfasst von / submitted by Kristina Höch, BA angestrebter akademischer Grad / in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (MA) Wien, 2016 / Vienna 2016 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt / A 066 582 degree programme code as it appears on the student record sheet: Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt / Masterstudium Theater-, Film- und Medientheorie degree programme as it appears on the student record sheet: Betreut von / Supervisor: Mag. Dr. habil. Ramón Reichert 1 Für meine Eltern. Ihr habt es erst möglich gemacht. Danke für absolut alles! Ihr seid die Besten! Danke Dani, dass du all die Jahre immer für mich da warst. Für all die Zeit, die du in wirre Schachtelsätze investiert hast, für deine aufmunternden Worte und die vielen Care Pakete mit Nervenfutter. Danke Andre, dass du meine Launen ertragen hast und immer an meiner Seite warst, vor allem dann, wenn mich Laptop und Drucker fast in den Wahnsinn getrieben hätten. Danke Johnny, dass du mir bei vielen Kinobesuchen und guten Gesprächen neue Perspektiven eröffnet hast. Ein großer Dank gilt auch Herrn Mag. Dr. habil. Ramón Reichert, der mich durch den Schreibprozess begleitet und mit hilfreichen Tipps und konstruktiver Kritik unterstützt hat. 2 3 Eidesstattliche Erklärung Ich erkläre hiermit an Eides Statt, dass ich die vorliegende Arbeit selbstständig und ohne Benutzung anderer als der angegebenen Hilfsmittel angefertigt habe. Die aus fremden Quellen direkt oder indirekt übernommenen Gedanken sind als solche kenntlich gemacht. -

Congratulations Class of 2014! 2 Student Life Getting Involved in the Stock Market Into Debt in Such a Short Period of Time, but Clearly It Is Very Pos- Sible

The Volume 74, Issue 3 RAMPARTThe Official Student Newspaper of Fordham Prep May 2014 A Tribute to a Great Teacher I enjoy museums, reading. Es- By LIAM NEUBAUER pecially reading and finding out recently had the outstanding more about artists. experience to sit down and talk Is there anything else you’d like to Fordham Prep’s art teacher, to mention? IMrs. Marilyn Honigman. Mrs. I just feel so lucky. I get to come Honigman has been at the Prep in everyday, do what I love, and for 35 years. Her full educational teach it! All these years have been career is at the Prep, and she is great and I’m going to miss it. a cherished member of our com- Mrs. Honigman’s love and munity. I was sad to learn that support for her students and art is she is retiring this year. She has overwhelming. She goes beyond done so much for this school, be being just an art teacher. She is it putting on art shows, running such an interesting person, being the art club, supplying and man- her student for a few years now aging numerous projects every I learned so much from her and year, and most of all inspiring her I wasn’t very good at much else, their mind what they’ve created. about her. She taught me many students. I was able to ask her and I always just loved art. I orig- I personally love to draw. things not only about art, but some questions, and this is what inally wanted to be a fashion de- What are you going to miss the about life. -

TV Review: Fargo Season 1 Episode 1: 'The Crocodile's

Nouse Web Archives TV Review: Fargo Season 1 Episode 1: ‘The Crocodile’s Dilema’ Page 1 of 3 News Comment MUSE. Politics Business Science Sport Roses Freshers Muse › Film & TV › Features Film Reviews TV Reviews Festivals TV Review: Fargo Season 1 Episode 1: ‘The Crocodile’s Dilema’ The opening episode of this crime thriller manages to capture the mood of the original while delivering a new and nail-biting story. Kate Barlow reviews Wednesday 23 April 2014 Rating: ★★★★★ Adapting an Oscar-winning well-loved cult film into a TV show only 18 years after its original release is a risky business. Especially given the fact that said film is directed by no other than the Coen brothers. However, in this grimly compelling crime thriller the high-risk strategy has paid off. Perhaps one of the first things that has to be said about the TV adaptation of Fargo is that it is in no way a remake. Despite the fact that the episode opens in the same way as the film, with a message claiming (falsely) that this is a true story, from here on the entire storyline of the first episode is different. While versions of characters from the film version remain (although their names have been changed) – we see Martin Freeman deliver a version of Jerry Lundegaard to perfection, along with Allison Tolman as an ambitious police detective not dissimilar to Marge Gunderson, truly giving Frances McDormand a run for her money – new characters are also introduced, giving the story a burst of originality. Billy Bob Thornton as the devilish do-what-you-want Lorne Malvo opens the episode, setting the dark broody atmosphere for the rest of the 68 minute runtime (and, hopefully, the rest of the series). -

Fergal TWOMEY Methodology As Teleology: the Economy of Secrets and Drama As Critique of Systems in the Works of Vince Gilligan A

Methodology as Teleology: The Economy of Secrets and Drama as Critique of Systems 133 in the Works of Vince Gilligan and Noah Hawley Fergal TWOMEY Methodology as Teleology: The Economy of Secrets and Drama as Critique of Systems in the Works of Vince Gilligan and Noah Hawley Abstract: In Noah Hawley’s Fargo, Lorne Malvo, a maverick loner who embodies sublime forces modulating human behaviour, states that he is a “student of institutions”. What serves as a glib and ironic remark on the arbitrary regulations of a small-town hostel raises questions about the aspirations and context of modern television. Traditional drama in this medium strives to portray human relationships on their psychological vague, through personal crises of love, family and identity as the force of character and plot development. A turn in recent series such as those of Vince Gilligan (Breaking Bad and Better Call Saul) and Noah Hawley (Fargo) presents a different form of drama. This is story as process, where the monomyth revolves around the circuitous navigation of institutions and processes by individuals, as well as the innovative manner in which they use and abuse them and, in turn, are used and abused by them in a struggle for agency. In this format, which has antecedents in procedural drama but departs radically from its conventions, the story is not driven by individual motives or ‘primal’ desires, but rather by the inhuman and dehumanising force which systems exert over the individuals contained within them. The cultural experience of fear and ambition in the era of consolidation of post-Fordist structures of life has departed from a paradigm of randomised fortune and misfortune to one of incorrigible and overlapping expectations, where the uncertainty behind both emotions is subaltern to the process-interaction that comprises a theory of systems. -

Fargo: Seeing the Significance of Style in Television Poetics?

Fargo: Seeing the significance of style in television poetics? By Max Sexton and Dominic Lees 6 Keywords: Poetics; Mini-series; Style; Storyworld; Coen brothers; Noah Hawley Abstract This article argues that Fargo as an example of contemporary US television serial drama renews the debate about the links between Televisuality and narrative. In this way, it seeks to demonstrate how visual and audio strategies de-stabilise subjectivities in the show. By indicating the viewing strategies required by Fargo, it is possible to offer a detailed reading of high-end drama as a means of understanding how every fragment of visual detail can be organised into a ‘grand’ aesthetic. Using examples, the article demonstrates how the construction of meaning relies on the formally playful use of tone and texture, which form the locus of engagement, as well as aesthetic value within Fargo. At the same time, Televisuality can be more easily explained and understood as a strategy by writers, directors and producers to construct discourses around increased thematic uncertainty that invites audience interpretation at key moments. In Fargo, such moments will be shown to be a manifestation not only of the industrial strategy of any particular network ‒ its branding ‒ but how is it part of a programme’s formal design. In this way, it is hoped that a system of television poetics ‒ including elements of camera and performance ‒ generates new insight into the construction of individual texts. By addressing television style as significant, it avoids the need to refer to pre-existing but delimiting categories of high-end television drama as examples of small screen art cinema, the megamovie and so on. -

The Rise of 'Bright Noir'. Redemption A

Author’s Accepted Manuscript (AAM) of the following chapter: García, Alberto N. "The Rise of 'Bright Noir'. Redemption and Moral Optimism in American Contemporary TV Noir", in European Television Crime Drama and Beyond, edited by Kim Toft Hansen, Steven Peacock, and Sue Turnbull, Palgrave, 2018, pp. 41- 60. Published version: https://www.palgrave.com/gp/book/9783319968865 1 The Rise of “Bright Noir” Redemption and Moral Optimism in American Contemporary TV Noir Alberto N. García Lou Solverson: We’re just out of balance. Betsy Solverson: You and me? Lou Solverson: Whole world. Used to know right from wrong. A moral centre. Now... (Fargo, “Fear and Trembling”, 2.4) Seated on the porch of their home, the Solversons reflect on evil and its masks, consequences and origins. Such ruminations have always been implicit, and sometimes explicit, in film noir since its emergence. However, as the above scene illustrates, Fargo (FX, 2014–) addresses evil from a classical moral perspective, as opposed to the anti- heroism and cynicism of angry, contradictory protagonists that have characterized the first decade of the golden age of television fiction (Martin 2013; Lotz 2014; Vaage 2015). Fargo is unlike other ‘quality TV’ crime series – such as The Sopranos (HBO, 1999–2007), The Wire (HBO, 2002–2008) or The Shield (FX, 2002–2008) – because the Solversons demonstrate hope, the “cousin” of optimism. Fargo embraces optimism, which, as defined by the anthropologist Lionel Tiger, is “a mood or attitude associated with an expectation about the social or material future—one which the evaluator regards as socially desirable, to his advantage, or for his pleasure” (1979, 53). -

Masculine Failure and Male Violence in Noah Hawley's Fargo

Journal of International Women's Studies Volume 21 Issue 3 Feminist Comforts and Considerations amidst a Global Pandemic: New Writings in Feminist and Women’s Studies—Winning and Article 8 Short-listed Entries from the 2020 Feminist Studies Association’s (FSA) Annual Student Essay Competition May 2020 Masculine Failure and Male Violence in Noah Hawley’s Fargo J. T. Weisser Follow this and additional works at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws Part of the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Weisser, J. T. (2020). Masculine Failure and Male Violence in Noah Hawley’s Fargo. Journal of International Women's Studies, 21(3), 90-106. Available at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol21/iss3/8 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. This journal and its contents may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. ©2020 Journal of International Women’s Studies. Masculine Failure and Male Violence in Noah Hawley’s Fargo By J. T. Weisser1 Abstract ‘Quality’ television drama is drama marketed as being filmic and boundary-pushing, yet it tackles the concept of masculinity in highly normative ways. Scholars argue that many quality television shows feature narratives of men struggling against emasculation at the hands of contemporary society before using violence to assert their masculinity by force. However, this interpretation is limited, assuming that all quality television shows which engage with violent masculinities root this violence in normative, ‘aggressive’ masculinity. -

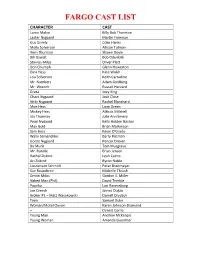

Fargo Cast List

FARGO CAST LIST CHARACTER CAST Lorne Malvo Billy Bob Thornton Lester Nygaard Martin Freeman Gus Grimly Colin Hanks Molly Solverson Allison Tolman Vern Thurman Shawn Doyle Bill Oswalt Bob Odenkirk Stavros Milos Oliver Platt Don Chumph Glenn Howerton Gina Hess Kate Walsh Lou Solverson Keith Carradine Mr. Numbers Adam Goldberg Mr. Wrench Russell Harvard Greta Joey King Chazz Nygaard Josh Close Nitty Nygaard Rachel Blanchard Moe Hess Liam Green Mickey Hess Atticus Mitchell Ida Thurman Julie Ann Emery Pearl Nygaard Kelly Holden Bashar Max Gold Brian Markinson Sam Hess Kevin O’Grady Wally Semenchko Barry Flatman Gordo Nygaard Pencer Drever Bo Munk Tom Musgrave Mr. Rundle Brian Jensen Rachel Ziskind Leah Cairns Ari Ziskind Byron Noble Lieutenant Schmidt Peter Breitmayer Sue Roundtree Michelle Thrush Dmitri Milos Gordon S. Miller Naked Man (Phil) David Trimble Paprika Lori Ravensborg Joe Creech James Dugan Broker #1 – Matt Wasakowski Darrell Orydzuk Teen Samuel Duke Woman/Motel Owner Karen Johnson-Diamond -- Dennis Corrie Young Man Andrew McKenzie Young Woman Amanda Guenther FARGO CASTING SCENE SELECTION FOR BLUE RIBBON PANEL/ RACHEL TENNER CD 1 EPISODE 101 3) Insurance Scene with the Couple 5:27- 6:10 Starts with: “So, that’s uh,…like I said” Ends with “I work at the library MARTIN FREEMAN/ ANDREW NEIL MCKENZIE (Young Man) / AMANDA GUETHNER (Young woman) 4) Sam Threatening Martin 9:14- 10:15 Starts With: “18 years, huh?” ends with Lester hitting the window and a little laugh from Sam MARTIN FREEMAN/ KEVIN O’GRADY (Sam HEss) / ATTICUS MITCHELL -

Revista 24 Cuadros

REVISTA 24 CUADROS TRUE REVISTAEspecial Series Volumen II Escriben: Acevedo / Vallarelli / Fonte / Giuffré / Gil / Cabana / Fili / Mastropaolo / Avila / Mazzini / Hernán Castaño / Mariano Castaño Especial Series - Vol II Revista 24 Cuadros - Año 11 Nº 32 Número 32 / Año 11 INDEX 24CUADROS True Detective - Tapa. Ud está aquí. Plot / Pág 3. En el Barrio se hablaba de tí por F. Vallarelli / Pág 4. True Detective por M. Acevedo y M. Castaño / Pág 5. The Night Of por F. Vallarelli / Pág 16. The Leftovers por A. Fili / Pág 18. The O.A. por Néstor Fonte / Pág 20. Black Mirror por Marcelo Acevedo / Pág 22. Cosmos por A. Fili / Pág 25. Stranger Things por M. Castaño / Pág 30. River por R. Giuffré / Pág 32. Mr. Robot por L. Avila / Pág 34. The Good Wife por A. Cabana / Pág 38. 3% por J.P. Mazzini / Pág 41. Westworld por A. Fili / Pág 44. Ash Vs Evil Dead por M. Acevedo / Pág 47. Bloodline por M y H Castaño / Pág 50. Fargo por F. Vallarelli / Pág 55. Preacher por L.Avila / Pág 58. Narcos por D. Pecchini y H. Castaño / Pág 61. Universo Marvel por M. Acevedo y H. Castaño / Pág 64. Series DC por F. Vallarelli / Pág 75. The Following y Lie To me por M. Gil / Pág 79. House of Cards por M. Castaño / Pág 83. Cuatro Nuevos Animes por E. Mastropaolo/ Pág 87. Staff / Pág 90. Mr. Robot por Yañez/ Pág 91. En las discusiones previas al armado de la revista, surgió la expresión temida por cualquier editor: “tal cosa no puede faltar”. -

Fargo #101 Production Draft

Executive Producer: Noah Hawley EPISODE: #101 Executive Producer: Warren Littlefield SCRIPT: #101 Executive Producers: Joel & Ethan Coen PRODUCTION: #1001 Executive Producer: Geyer Kosinski Co-Executive Producer: John Cameron Directed by: Adam Bernstein Inspired by the feature film By Joel and Ethan Coen “The Crocodile’s Dilemma” Episode #101 Script by Noah Hawley GREEN PRODUCTION DRAFT – FULL 11/1/13 Prep Starts: 9/23 Shoot Dates: 11/4 – 12/4 26 Keys Productions The Littlefield Company Nomadic Pictures MGM Television FX Network MGM Television Entertainment Inc. 245 North Beverly Drive Beverly Hills, CA 90210 © 2013 MGM Television Entertainment Inc. All Rights Reserved. F A R G O Episode #101 “The Crocodile’s Dilemma” GREEN FULL PRODUCTION DRAFT 11.1.13 REVISION HISTORY FULL GREEN PRODUCTION DRAFT 11/1/13 YELLOW PRODUCTION DRAFT – REVISED PAGES 10/25/13 FULL PINK PRODUCTION DRAFT 10/18/13 FULL BLUE PRODUCTION DRAFT 10/3/13 FULL WHITE PRODUCTION DRAFT 8/28/13 WRITER’S DRAFT 4/3/13 NOTES: GREEN DRAFT REVISIONS - Sc. 2 description changes - Sc. 3 dialogue change - Sc. 6 description and dialogue change - Sc. 8 dialogue change - Sc. 9 time of day change to DAY, dialogue change - Sc. 10, 11, 12, 13 time of day change to DAY - Sc. 14 character name change, dialogue change - Sc. 15, 16, 17 character, dialogue, description and location name changes - Sc. 27, 28 location name change - Sc. 29, 30 dialogue change - Sc. 31 character name change - Sc. 34 character name and dialogue changes - Sc. 35, 36 description changes - Sc. 38 location name change - Sc. 39 dialogue changes - Sc. -

Fargo Series Document 7.18.13

F a r g o S e r i e s D o c u m e n t N o a h H a w l e y T h e L i t t l e f i e l d C o m p a n y M G M F X J u l y 23 , 2 0 1 3 Far·go (fär g ) 1. A city of eastern North Dakota on the Red River east of Bismarck. Founded with the coming of the railroad in 1871, it is the largest city in the state. Population: 90,100. 2.A unique brand of true crime story, part tragedy, part farce, in which simple, good hearted people come face to face with something monstrous. 2 THIS IS THE STORY of a CRIMINAL who meets a spineless insurance salesman and agrees to kill his bully, mostly because he wants to see how far he can push the insurance salesman before he snaps. IT’S THE STORY of an INSURANCE SALESMAN who asks the Criminal to kill his bully, then beats his own wife to death, and lies, and cheats and steals to get away with it. IT’S THE STORY of a young, FEMALE POLICE DEPUTY trying to figure out who killed the insurance salesman’s wife, shot the police chief, stabbed a local trucking boss in a whorehouse, and who exactly is the dead naked guy in the woods. IT’S THE STORY of a widowed STATE PATROLMAN who lets the Criminal escape, and then feels compelled to track him down.