The First European Observatory Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(ISU) at the University of Marburg

In This Issue: March 21, 2016 Hessen International Summer University (ISU) at the University of Marburg Hessen International Summer University (ISU) at the University of Marburg Find your MBA, Master or Double Degree at the International Graduate Center in Bremen! Start your MBA programme in Germany at Kempten University of Applied Sciences Register now for the 2016 BSUA Berlin programme to work on your artistic The Hessen International Summer University (ISU) at the Philipps- potentials! Universität Marburg is a four-week summer study program, open to all candidates looking to combine their academic studies with an exciting Masters Programs at The Center for intercultural experience. Global Politics at Freie Universität The program offers an intensive German course (all levels, also for Berlin beginners), specialized seminars in English, credits (up to 9 ECTS), weekend field trips to various destinations in Germany and France and more! Vi si t: daad.org ISU in a nutshell Emai l: [email protected] Dates: July 16 August 13, 2016 Program Topic: Business, Politics, and Conflicts in a Changing World. Selected Topics in: Business and Accounting Peace and Conflict Studies Middle Eastern Studies German Studies. Requirements: Applicants are expected to have a level of English language proficiency sufficient to participate in the academic and social environment of the program. Application documentation will include a letter of motivation and a transcript of records. Apply by March 31, 2016 and get an early-bird discount off the program fee! -

Preliminary Ruling Requested by the Verwaltungsgericht Kassel

JUDGMENT OF THE COURT OF 31 JANUARY 1979<appnote>1</appnote> Yoshida GmbH v Industrie- und Handelskammer Kassel (preliminary ruling requested by the Verwaltungsgericht Kassel) "Slide fasteners" Case 114/78 1. Goods — Slide fasteners — Origin — Determination thereof — Criteria — Commission Regulation (EEC) No 2067/77, Art. 1 — Invalid In adopting Regulation (EEC) No Regulation (EEC) No 802/68 of the 2067/77 concerning the determination of Council. Article 1 of Regulation No the origin of slide fasteners, the 2067/77 is therefore invalid. Commission exceeded its power under In Case 114/78 REFERENCE to the Court under Article 177 of the EEC Treaty by the Verwaltungsgericht Kassel for a preliminary ruling in the action pending before that court between Yoshida GmbH, Mainhausen (Federal Republic of Germany) and Industrie- und Handelskammer Kassel on the validity of Commission Regulation (EEC) No 2067/77 concerning the determination of the origin of slide fasteners (Official Journal L 242 of 21 September 1977, p. 5), 1 — Language of the Case: German. 151 JUDGMENT OF 31. 1. 1979 — CASE 114/78 THE COURT composed of: H. Kutscher, President, J. Mertens de Wilmars and Lord Mackenzie Stuart (Presidents of Chambers), A. M. Donner, P. Pescatore, M. Sørensen, A. O'Keeffe, G. Bosco and A. Touffait, Judges, Advocate General: F. Capotorti Registrar: A. Van Houtte gives the following JUDGMENT Facts and Issues The facts of the case, procedure, origin certifying that its products are conclusions and submissions and of German origin or possibly of arguments of the parties may be Community origin. Whereas these certi• summarized as follows: ficates have hitherto been granted under Article 5 of Regulation (EEC) No I — Facts and procedure 802/68 of 27 June 1968 on the common definition of the concept of the origin of The plaintiff in the main action is a sub• goods in so far as the value of the raw sidiary of the Yoshida Kogyo K. -

The Federal State of Hesse

Helaba Research REGIONAL FOCUS 7 August 2018 Facts & Figures: The Federal State of Hesse AUTHOR The Federal Republic of Germany is a country with a federal structure that consists of 16 federal Barbara Bahadori states. Hesse, which is situated in the middle of Germany, is one of them and has an area of just phone: +49 69/91 32-24 46 over 21,100 km2 making it a medium-sized federal state. [email protected] EDITOR Hesse in the middle of Germany At 6.2 million, the population of Hesse Dr. Stefan Mitropoulos/ Population in millions, 30 June 2017 makes up 7.5 % of Germany’s total Anna Buschmann population. In addition, a large num- PUBLISHER ber of workers commute into the state. Dr. Gertrud R. Traud As a place of work, Hesse offers in- Chief Economist/ Head of Research Schleswig- teresting fields of activity for all qualifi- Holstein cation levels, for non-German inhabit- Helaba 2.9 m Mecklenburg- West Pomerania ants as well. Hence, the proportion of Landesbank Hamburg 1.6 m Hessen-Thüringen 1.8 m foreign employees, at 15 %, is signifi- MAIN TOWER Bremen Brandenburg Neue Mainzer Str. 52-58 0.7 m 2.5 m cantly higher than the German aver- 60311 Frankfurt am Main Lower Berlin Saxony- age of 11 %. phone: +49 69/91 32-20 24 Saxony 3.6 m 8.0 m Anhalt fax: +49 69/91 32-22 44 2.2 m North Rhine- Apart from its considerable appeal for Westphalia 17.9 m immigrants, Hesse is also a sought- Saxony Thuringia 4.1 m after location for foreign direct invest- Hesse 2.2 m 6.2 m ment. -

Chronik Des Werra-Meißner-Kreises Anlässlich Des 40-Jährigen Jubiläums Der Kreisgründung

Chronik des Werra-Meißner-Kreises anlässlich des 40-jährigen Jubiläums der Kreisgründung Diese Publikation wurde durch die freundliche Unterstützung der Sparkasse Werra-Meißner möglich. 2 Inhaltsverzeichnis / Impressum 1. Vorwort 3 2. Einleitung 4 3. Die territoriale Vorgeschichte der Region um Werra und Meißner 4 3.1. Von der Landvogtei an der Werra zum Distrikt Eschwege – Die Werra-Meißner-Region zwischen Spätmittelalter und Franzosenherrschaft 4 3.1.1. Der hessisch-thüringische Erbfolgekrieg 4 3.1.2. Die Städte und Ämter im Werraland 5 3.1.3. Die Landvogtei an der Werra 5 3.1.4. Die Landvogtei nach dem „Sterner“-Krieg 5 3.1.5. Landadel muss hessische Landeshoheit anerkennen 6 3.1.6. Das Werraland im „Ökonomischen Staat“ und seine Verwaltungsorganisation 6 3.1.7. Die Rotenburger Quart 7 3.1.8. Teil des „Königreiches Westphalen“ 7 4. Verwaltungsgeschichte der Kreise Eschwege und Witzenhausen 1821–1945 8 4.1. Die kurhessische Verwaltungsreform von 1821 und die Gründung der Landkreise Eschwege und Witzenhausen 8 4.1.1. Von der Kreisgründung 1821 bis zur bürgerlichen Revolution 1848 8 4.1.2. 1848 und die Folgen: Demokratisches Zwischenspiel 10 4.1.3. 1851–1866 11 4.1.4. Die Kreise Eschwege und Witzenhausen im Kaiserreich (1866–1918) 11 4.1.5. Kreis Eschwege 12 4.1.6. Kreis Witzenhausen 13 4.2. Die Kreise Eschwege und Witzenhausen zur Zeit der Weimarer Republik und des „Dritten Reiches“ 1918–1945 14 4.2.1. Kreis Eschwege 14 4.2.2. Kreis Witzenhausen 17 5. Von der Stunde „Null “ zur Gebietsreform 21 5.1. Wiedergeburt der Demokratie und Integration der Flüchtlinge 21 5.2. -

Marburg Hemorrhagic Fever Fact Sheet

Marburg Hemorrhagic Fever Fact Sheet What is Marburg hemorrhagic fever? Marburg hemorrhagic fever is a rare, severe type of hemorrhagic fever which affects both humans and non-human primates. Caused by a genetically unique zoonotic (that is, animal-borne) RNA virus of the filovirus family, its recognition led to the creation of this virus family. The four species of Ebola virus are the only other known members of the filovirus family. Marburg virus was first recognized in 1967, when outbreaks of hemorrhagic fever occurred simultaneously in laboratories in Marburg and Frankfurt, Germany and in Belgrade, Yugoslavia (now Serbia). A total of 37 people became ill; they included laboratory workers as well as several medical personnel and Negative stain image of an isolate of Marburg virus, family members who had cared for them. The first people showing filamentous particles as well as the infected had been exposed to African green monkeys or characteristic "Shepherd's Crook." Magnification their tissues. In Marburg, the monkeys had been imported approximately 100,000 times. Image courtesy of for research and to prepare polio vaccine. Russell Regnery, Ph.D., DVRD, NCID, CDC. Where do cases of Marburg hemorrhagic fever occur? Recorded cases of the disease are rare, and have appeared in only a few locations. While the 1967 outbreak occurred in Europe, the disease agent had arrived with imported monkeys from Uganda. No other case was recorded until 1975, when a traveler most likely exposed in Zimbabwe became ill in Johannesburg, South Africa – and passed the virus to his traveling companion and a nurse. 1980 saw two other cases, one in Western Kenya not far from the Ugandan source of the monkeys implicated in the 1967 outbreak. -

Göttingen Eichenberg Esch W Eg E Bebra Achtung: Baustellenbedingte

Montag - Freitag r 4 Linie RB87 RB87 RB87 RB87 RB87 RB87 RB87 RB87 RB87 RB87 RB87 RB87 RB87 RB87 RB87 RB87 Verkehrsbeschränkungen Anmerkungen Göttingen ab 4.14 5.14 6.14 6.59 8.14 9.14 10.14 11.14 12.14 13.14 14.14 15.14 16.14 17.14 18.14 19.14 Friedland (Han) 4.23 5.24 6.23 7.09 8.23 9.23 10.23 11.23 12.23 13.23 14.23 15.23 16.23 17.23 18.23 19.23 Eichenberg an 4.28 5.28 6.28 7.14 8.28 9.28 10.28 11.28 12.28 13.28 14.28 15.28 16.28 17.28 18.28 19.28 RB87 Eichenberg ab 4.30 5.30 6.30 7.15 8.30 9.30 10.30 11.30 12.30 13.30 14.30 15.30 16.30 17.30 18.30 19.30 Bad Sooden-Allendorf 4.40 5.40 6.40 7.25 8.40 9.40 10.40 11.40 12.40 13.40 14.40 15.40 16.40 17.40 18.40 19.40 Eschwege-Niederhone 4.48 5.48 6.48 7.33 8.48 9.48 10.48 11.48 12.48 13.48 14.48 15.48 16.48 17.48 18.48 19.48 Eschwege an 4.51 5.51 6.51 7.36 8.51 9.51 10.51 11.51 12.51 13.51 14.51 15.51 16.51 17.51 18.51 19.51 Eschwege ab 4.59 5.59 6.59 7.59 8.59 9.59 10.59 11.59 12.59 13.59 14.59 15.59 16.59 17.59 18.59 19.59 Wehretal-Reichensachsen 5.06 6.06 7.06 8.06 9.06 10.06 11.06 12.06 13.06 14.06 15.06 16.06 17.06 18.06 19.06 20.06 Sontra 5.12 6.12 7.12 8.12 9.12 10.12 11.12 12.12 13.12 14.12 15.12 16.12 17.12 18.12 19.12 20.12 Bebra an 5.26 6.26 7.26 8.26 9.26 10.26 11.26 12.26 13.26 14.26 15.26 16.26 17.26 18.26 19.26 20.26 r RE5/RB5 Bebra ab 5.59 6.42 7.31 8.34 9.35 10.31 11.31 12.31 13.35 14.31 15.35 16.31 17.35 18.31 19.35 20.31 r RE5/RB5 Bad Hersfeld an 6.09 6.53 7.42 8.45 9.45 10.41 11.41 12.41 13.45 14.41 15.45 16.41 17.45 18.41 19.45 20.41 r RE5/RB5 Bebra ab 5.33 6.33 7.33 -

Escaping Liberty: Western Hegemony, Black Fugitivity Barnor Hesse Political Theory 2014 42: 288 DOI: 10.1177/0090591714526208

Political Theory http://ptx.sagepub.com/ Escaping Liberty: Western Hegemony, Black Fugitivity Barnor Hesse Political Theory 2014 42: 288 DOI: 10.1177/0090591714526208 The online version of this article can be found at: http://ptx.sagepub.com/content/42/3/288 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com Additional services and information for Political Theory can be found at: Email Alerts: http://ptx.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://ptx.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav >> Version of Record - May 14, 2014 What is This? Downloaded from ptx.sagepub.com by guest on May 20, 2014 PTXXXX10.1177/0090591714526208Political TheoryHesse 526208research-article2014 Article Political Theory 2014, Vol. 42(3) 288 –313 Escaping Liberty: © 2014 SAGE Publications Reprints and permissions: Western Hegemony, sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/0090591714526208 Black Fugitivity ptx.sagepub.com Barnor Hesse1 Abstract This essay places Isaiah Berlin’s famous “Two Concepts of Liberty” in conversation with perspectives defined as black fugitive thought. The latter is used to refer principally to Aimé Césaire, W. E. B. Du Bois and David Walker. It argues that the trope of liberty in Western liberal political theory, exemplified in a lineage that connects Berlin, John Stuart Mill and Benjamin Constant, has maintained its universal meaning and coherence by excluding and silencing any representations of its modernity gestations, affiliations and entanglements with Atlantic slavery and European empires. This particular incarnation of theory is characterized as the Western discursive and hegemonic effects of colonial-racial foreclosure. Foreclosure describes the discursive contexts in which particular terms or references become impossible to formulate because the means by which they could be formulated have been excluded from the discursive context. -

MARBURG HEMORRHAGIC FEVER (Marburg HF)

MARBURG HEMORRHAGIC FEVER (Marburg HF) REPORTING INFORMATION • Class A: Report immediately via telephone the case or suspected case and/or a positive laboratory result to the local public health department where the patient resides. If patient residence is unknown, report immediately via telephone to the local public health department in which the reporting health care provider or laboratory is located. Local health departments should report immediately via telephone the case or suspected case and/or a positive laboratory result to the Ohio Department of Health (ODH). • Reporting Form(s) and/or Mechanism: o Immediately via telephone. o For local health departments, cases should also be entered into the Ohio Disease Reporting System (ODRS) within 24 hours of the initial telephone report to the ODH. • Key fields for ODRS reporting include: import status (whether the infection was travel-associated or Ohio-acquired), date of illness onset, and all the fields in the Epidemiology module. AGENT Marburg hemorrhagic fever is a rare, severe type of hemorrhagic fever which affects both humans and non-human primates. Caused by a genetically unique zoonotic RNA virus of the family Filoviridae, its recognition led to the creation of this virus family. The five species of Ebola virus are the only other known members of the family Filoviridae. Marburg virus was first recognized in 1967, when outbreaks of hemorrhagic fever occurred simultaneously in laboratories in Marburg and Frankfurt, Germany and in Belgrade, Yugoslavia (now Serbia). A total of 31 people became ill, including laboratory workers as well as several medical personnel and family members who had cared for them. -

French and Hessian Impressions: Foreign Soldiers' Views of America During the Revolution

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2003 French and Hessian Impressions: Foreign Soldiers' Views of America during the Revolution Cosby Williams Hall College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Military History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Hall, Cosby Williams, "French and Hessian Impressions: Foreign Soldiers' Views of America during the Revolution" (2003). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626414. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-a7k2-6k04 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FRENCH AND HESSIAN IMPRESSIONS: FOREIGN SOLDIERS’ VIEWS OF AMERICA DURING THE REVOLUTION A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Cosby Hall 2003 a p p r o v a l s h e e t This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts CosbyHall Approved, September 2003 _____________AicUM James Axtell i Ronald Hoffman^ •h im m > Ronald S chechter TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Acknowledgements iv Abstract V Introduction 2 Chapter 1: Hessian Impressions 4 Chapter 2: French Sentiments 41 Conclusion 113 Bibliography 116 Vita 121 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The writer wishes to express his sincere appreciation to Professor James Axtell, under whose guidance this paper was written, for his advice, editing, and wisdom during this project. -

Anlage 5 Tabellen Der Natura 2000-Gebiete, Die Mit Ihrem Größeren Flächenanteil in Einem Der Nachbarregierungsbezirke Liegen

Anlage 5 Tabellen der Natura 2000-Gebiete, die mit ihrem größeren Flächenanteil in einem der Nachbarregierungsbezirke liegen und daher in der dortigen Natura 2000-Verordnung gesichert werden. Sie sind in dieser Anlage nur nachrichtlich aufgeführt und in der Übersichtskarte (Anlage 2) zu dieser Verordnung nur nachrichtlich mit dünner blauer Schraffur dargestellt oder bei sehr schmalen linienhaften Fließgewässergebieten mit einem textli- chen Hinweis in der Karte „Rechtliche Sicherung durch das benannte Nachbarregierungspräsidium“ versehen. Tabelle der RP-übergreifenden FFH-Gebiete mit dem größten Flächenanteil im Regierungsbezirk Darmstadt, die in der Übersichtkarte dieser Verord- nung mit dünner blauer Schraffur und Natura-Nummer nachrichtlich dargestellt werden NATURA_NR NAME HA REG_BEZ KREIS GEMEINDE 5518-301 Salzwiesen von Münzenberg 64.20 Darmstadt, Wetteraukreis, Gießen, Münzenberg, Lich Gießen 5520-302 Talauen von Nidder und Hillersbach 253,90 Darmstadt, Wetteraukreis, Vogelsbergkreis Gedern, Schotten bei Gedern und Burkhards Gießen 5520-306 Waldgebiete südlich und südwestlich 1680,60 Darmstadt, Wetteraukreis, Vogelsbergkreis Hirzenhain, Nidda, Schot- von Schotten Gießen ten 5622-310 Steinaubachtal und Ürzeller Wasser 45,30 Darmstadt, Main-Kinzig-Kreis, Vogelsbergkreis Steinau an der Straße, Gießen Schlüchtern, Freiensteinau Tabelle der RP-übergreifenden schmalen linienhaften Fließgewässer-FFH-Gebiete mit dem größten Flächenanteil im Regierungsbezirk Darmstadt, die in der Übersichtkarte dieser Verordnung mit dem textlichen Hinweis -

![MARBURG VIRUS [African Hemorrhagic Fever, Green Or Vervet Monkey Disease]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3334/marburg-virus-african-hemorrhagic-fever-green-or-vervet-monkey-disease-883334.webp)

MARBURG VIRUS [African Hemorrhagic Fever, Green Or Vervet Monkey Disease]

MARBURG VIRUS [African Hemorrhagic Fever, Green or Vervet Monkey Disease] SPECIES: Nonhuman primates, especially african green monkeys & macaques AGENT: Agent is classified as a Filovirus. It is an RNA virus, superficially resembling rhabdoviruses but has bizarre branching and filamentous or tubular forms shared with no other known virus group on EM. The only other member of this class of viruses is ebola virus. RESERVOIR AND INCIDENCE: An acute highly fatal disease first described in Marburg, Germany in 1967. Brought to Marburg in a shipment of infected African Green Monkeys from Uganda. 31 people were affected and 7 died in 1967. Exposure to tissue and blood from African Green monkeys (Cercopithecus aethiops) or secondary contact with infected humans led to the disease. No disease occurred in people who handled only intact animals or those who wore gloves and protective clothing when handling tissues. A second outbreak was reported in Africa in 1975 involving three people with no verified contact with monkeys. Third and fourth outbreaks in Kenya 1980 and 1987. Natural reservoir is unknown. Monkeys thought to be accidental hosts along with man. Antibodies have been found in African Green monkeys, baboons, and chimpanzees. 100% fatal in experimentally infected African Green Monkeys, Rhesus, squirrel monkeys, guinea pigs, and hamsters. TRANSMISSION: Direct contact with infected blood or tissues or close contact with infected patients. Virus has also been found in semen, saliva, and urine. DISEASE IN NONHUMAN PRIMATES: No clinical signs occur in green monkeys, but the disease is usually fatal after experimental infection of other primate species. Leukopenia and petechial hemorrhages throughout the body of experimentally infected monkeys, sometimes with GI hemorrhages. -

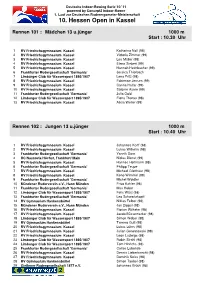

10. Hessen Open in Kassel

Deutsche Indoor-Rowing Serie`10/`11 powered by Concept2 Indoor-Rower 1. Lauf zur Deutschen Ruderergometer-Meisterschaft 10. Hessen Open in Kassel Rennen 101 : Mädchen 13 u.jünger 1000 m Start : 10.30 Uhr 1 RV Friedrichsgymnasium Kassel Katharina Noll (98) 2 RV Friedrichsgymnasium Kassel Victoria Zimmer (99) 3 RV Friedrichsgymnasium Kassel Lea Müller (98) 4 RV Friedrichsgymnasium Kassel Elena Siebert (99) 5 RV Friedrichsgymnasium Kassel Hannah Heimbucher (99) 6 Frankfurter Rudergesellschaft 'Germania' Jessica Thierbach 7 Limburger Club für Wassersport 1895/1907 Lena Fritz (98) 8 RV Friedrichsgymnasium Kassel Fabienne Jensen (99) 9 RV Friedrichsgymnasium Kassel Carina Halfar (99) 10 RV Friedrichsgymnasium Kassel Salome Asare (99) 11 Frankfurter Rudergesellschaft 'Germania' Julia Gold 12 Limburger Club für Wassersport 1895/1907 Fiona Thurau (98) 13 RV Friedrichsgymnasium Kassel Alicia Weller (99) Rennen 102 : Jungen 13 u.jünger 1000 m Start : 10.40 Uhr 1 RV Friedrichsgymnasium Kassel Johannes Korff (98) 2 RV Friedrichsgymnasium Kassel Lukas Wilhelm (98) 3 Frankfurter Rudergesellschaft 'Germania' Yannik Dorn 4 RC Nassovia Höchst, Frankfurt/ Main Niclas Dienst (99) 5 RV Friedrichsgymnasium Kassel Hannes Heitmann (98) 6 Frankfurter Rudergesellschaft 'Germania' Philipp Teupe 7 RV Friedrichsgymnasium Kassel Michael Glatthaar (98) 8 RV Friedrichsgymnasium Kassel Keno Wimmel (98) 9 Frankfurter Rudergesellschaft 'Germania' Michel Woldter 10 Mündener Ruderverein e.V., Hann Münden Friso Kahler (98) 11 Frankfurter Rudergesellschaft 'Germania' Max Huber