The Neighborly Substation the Neighborly Substation Electricity, Zoning, and Urban Design

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Valley & Spruce Project Initial Study and Mitigated

VALLEY & SPRUCE PROJECT INITIAL STUDY AND MITIGATED NEGATIVE DECLARATION Prepared for: City of Rialto December 2017 VALLEY & SPRUCE PROJECT INITIAL STUDY AND MITIGATED NEGATIVE DECLARATION Prepared For: City of Rialto 150 S. Palm Avenue Rialto, CA 92376 Prepared By: Kimley-Horn and Associates, Inc. 401 B Street, Suite 600 San Diego, California 92101 December 2017 095894012 Copyright © 2017 Kimley-Horn and Associates, Inc. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Initial Study ............................................................................................................................................ 1 II. Description of Proposed Project ........................................................................................................... 2 III. Required Permits ................................................................................................................................... 8 IV. Environmental Factors Potentially Affected ......................................................................................... 9 V. Determination ........................................................................................................................................ 9 VI. Environmental Evaluation .................................................................................................................. 10 1. Aesthetics ................................................................................................................................ 10 2. Agricultural and Forestry Resources ..................................................................................... -

Use F-Response Cloud Connector to Access Google Drive Cloud Storage

F-Response Mission Guide Email:[email protected] Using the F-Response Cloud Connector with Google Drive Website:www.f-response.com Rev 1.0 Phone: 1-800-317-5497 Your Mission: Use F-Response Cloud Connector to access Google Drive Cloud Storage Note: This guide assumes you have installed F-Response TACTICAL, Consultant, Consultant + Covert, or Enterprise, your F-Response licensing dongle is plugged into your analyst machine, and the F-Response Cloud Connector (FCLDC) has been started. For more information, please reference the F-Response User Manual. Step 1: Open Google Drive Credential Configuration window Before you can connect to Google Drive you must first input valid credentials. In the F-Response Cloud Storage Connector go to File->Configure Credentials-> Configure Google Drive Credentials. Cloud Storage Connector Step 2: Open URL or Copy to Clipboard The first step in obtaining access to the Google Drive account is to request access either via the browser directly, or if you do not have access to the account in question, copying the request URL to the clipboard to be shared with the account holder via email, IM, etc. Regardless of the method chosen, the web browser user will be asked to login to Google Drive and authorize the F- Response Cloud Connector, upon completion they will be redirected to the F-Response website where an Authorization code will be presented. This is the Google Drive Authorization Code and must be inputed into the dialog box as indicated: F-Response Mission Guide Email:[email protected] Using the F-Response Cloud Connector with Google Drive Website:www.f-response.com Rev 1.0 Phone: 1-800-317-5497 Press Validate Access and the dialog will now present the User Account name, UID, and additional details in the Confirm Account section. -

Form E – Testing Accommodations

THE STATE BAR OF CALIFORNIA CALIFORNIA BOARD OF LEGAL SPECIALIZATION/OFFICE OF ADMISSIONS 180 Howard Street • San Francisco, CA 94105-1639 • (415) 538-2300 845 S. Figueroa Street • Los Angeles, CA 90017-2515 • (213) 765-1500 FORM E TESTING ACCOMMODATIONS – PSYCHOLOGICAL DISABILITIES VERIFICATION All original documents must be filed with the Office of Admissions’ San Francisco Office. (Must be completed by the applicant; please type or print legibly) NOTICE TO APPLICANT: This section of this form is to be completed by you. The remainder of the form is to be completed by the qualified professional who is recommending testing accommodations for the Legal Specialist Examination for you on the basis of a psychological disability. Please read, complete, and sign below before submitting this form to the qualified professional for completion of the remainder of this form. Applicant’s Full Name: Bar Number: I give permission to the qualified professional completing this form to release the information requested on the form, and I request the release of any additional information regarding my disability or accommodations previously granted that may be requested by the California Board of Legal Specialization or consultant(s) of the California Board of Legal Specialization. Signature of Applicant Date NOTICE TO QUALIFIED PROFESSIONAL: The above-named person is requesting accommodations for the Legal Specialist Examination. All such requests must be supported by a comprehensive evaluation report from the qualified professional who conducted an individualized assessment of the applicant and is recommending accommodations for the examination on the basis of a psychological disability. The California Board of Legal Specialization also requires the qualified professional to complete this form. -

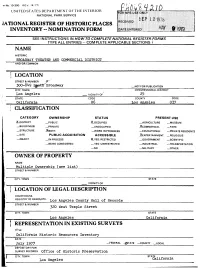

Jational Register of Historic Places Inventory -- Nomination Form

•m No. 10-300 REV. (9/77) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE JATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ____________TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS >_____ NAME HISTORIC BROADWAY THEATER AND COMMERCIAL DISTRICT________________________ AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREET & NUMBER <f' 300-8^9 ^tttff Broadway —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Los Angeles VICINITY OF 25 STATE CODE COUNTY CODE California 06 Los Angeles 037 | CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE X.DISTRICT —PUBLIC ^.OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED .^COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE .XBOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE ^ENTERTAINMENT _ REUGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS 2L.YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: NAME Multiple Ownership (see list) STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE VICINITY OF | LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDSETC. Los Angeie s County Hall of Records STREET & NUMBER 320 West Temple Street CITY. TOWN STATE Los Angeles California ! REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TiTLE California Historic Resources Inventory DATE July 1977 —FEDERAL ^JSTATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS office of Historic Preservation CITY, TOWN STATE . ,. Los Angeles California DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED ^ORIGINAL SITE X.GOOD 0 —RUINS X_ALTERED _MOVED DATE- —FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Broadway Theater and Commercial District is a six-block complex of predominately commercial and entertainment structures done in a variety of architectural styles. The district extends along both sides of Broadway from Third to Ninth Streets and exhibits a number of structures in varying condition and degree of alteration. -

Volume I Restoration of Historic Streetcar Service

VOLUME I ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT RESTORATION OF HISTORIC STREETCAR SERVICE IN DOWNTOWN LOS ANGELES J U LY 2 0 1 8 City of Los Angeles Department of Public Works, Bureau of Engineering Table of Contents Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................................. ES-1 ES.1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................... ES-1 ES.2 Purpose and Need ............................................................................................................................................... ES-1 ES.3 Background ............................................................................................................................................................ ES-2 ES.4 7th Street Alignment Alternative ................................................................................................................... ES-3 ES.5 Safety ........................................................................................................................................................................ ES-7 ES.6 Construction .......................................................................................................................................................... ES-7 ES.7 Operations and Ridership ............................................................................................................................... -

Two Bells October 26, 1925

I £ PEDRO ■■■ n 0 s BELLS VoL. VI OCTOBER 26. 1925 No. 22 A Herald of Good Cheer and Cooperation Published by and for Employes of the Los Angeles Railway Edited by J. G. JEFFERY, Director of Public Relations Community Chest Drive Outlined Billy Snyder, Married Division 1 Makes G. B. A. BACK 20 Consecutive Y ears, NINE MAJORS Given Suprise Party 99 Percent Mark In Association FROM EAST IN celebration of the twentieth wed- FOR SECOND ding anniversary of Mr. and Mrs. W. H. Snyder, an enthusiastic but or- DIVISION One has set a high derly party of supervisors and dis- mark in the Wives' Death WITH NEW patchers descended upon the family benefit branch of the Coopera- CHARITY home at 1104 West Thirty-eighth tive Association. Ninety-nine street October 17, as unexpectedly as per cent of the men under Su- a prohibition enforcement raiding perintendent E. C. Williams who squad, and proceeded to "throw a are eligible to participate in this IDEAS party." Mr. Snyder has been with the branch of the Association have APPEAL Los Angeles Railway 23 years, and is filed the necessary cards. now assistant director of traffic. The Wives' Death benefit Organization of the various depart- George Baker Anderson, manager of The big moment of the evening branch is intended to increase transportation, and R. B. Hill, super- came when W. B. Adams, director of ments of the Los Angeles Railway for the value of the Association. An participation in the second annual intendent of operation, have returned traffic, presented Mr. and Mrs. -

High Voltage Direct Current Transmission – Proven Technology for Power Exchange

www.siemens.com/energy/hvdc High Voltage Direct Current Transmission – Proven Technology for Power Exchange Answers for energy. 2 Contents Chapter Theme Page 1 Why High Voltage Direct Current? 4 2 Main Types of HVDC Schemes 6 3 Converter Theory 8 4 Principle Arrangement of an HVDC Transmission Project 11 5 Main Components 14 5.1 Thyristor Valves 14 5.2 Converter Transformer 18 5.3 Smoothing Reactor 20 5.4 Harmonic Filters 22 5.4.1 AC Harmonic Filter 22 5.4.2 DC Harmonic Filter 25 5.4.3 Active Harmonic Filter 26 5.5 Surge Arrester 28 5.6 DC Transmission Circuit 31 5.6.1 DC Transmission Line 31 5.6.2 DC Cable 32 5.6.3 High Speed DC Switches 34 5.6.4 Earth Electrode 36 5.7 Control & Protection 38 6 System Studies, Digital Models, Design Specifications 45 7 Project Management 46 3 1 Why High Voltage Direct Current? 1.1 Highlights from the High Voltage Direct In 1941, the first contract for a commercial HVDC Current (HVDC) History system was signed in Germany: 60 MW were to be supplied to the city of Berlin via an underground The transmission and distribution of electrical energy cable of 115 km length. The system with ±200 kV started with direct current. In 1882, a 50-km-long and 150 A was ready for energizing in 1945. It was 2-kV DC transmission line was built between Miesbach never put into operation. and Munich in Germany. At that time, conversion between reasonable consumer voltages and higher Since then, several large HVDC systems have been DC transmission voltages could only be realized by realized with mercury arc valves. -

Operational and Safety Considerations for Light Rail DC Traction Electrification System Design

LIGHT RAIL ELECTRIFICATION Operational and Safety Considerations for Light Rail DC Traction Electrification System Design KINH D. PHAM Elcon Associates, Inc., Engineers & Consultants RALPH S. THOMAS WALTER E. STINGER, JR. LTK Engineering Services n overview is presented of an integrated approach to operational and safety issues when A designing a DC traction electrification system (TES) for modern light rail and streetcar systems. First, the human body electrical circuit model is developed, and tolerable step and touch potentials derived from IEEE Standard 80 are defined. Touch voltages that are commonly present around the rails, at station platforms, at traction power substations are identified and analyzed. Operational and safety topics discussed include • Applicable codes and standards for electrical safety; • Traction power substation (TPS) grounding; • Detection of ground faults; • DC protective relaying schemes including rail-to-earth voltage sensing and nuisance tripping, and transfer tripping of adjacent substations; • TES system surge protection; • Electromagnetic and induced voltage problems that could cause disturbances in the signaling system; • DC stray currents that can cause corrosion and damage to the negative return system, underground utilities, telecommunication cables, and other metallic structures; and • Emergency shutdown trip stations (ETS). To ensure safety of the project personnel and the public, extensive testing and proper and safe equipment operation, are required. The testing includes factory testing of the DC protection system, first article inspection of critical TES components, inspection and field testing during commissioning. In addition, safety certification must be accomplished before the TES system is energized and put into operation. INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW The TES for a typical modern light rail or street car system includes an overhead contact system (OCS), traction power substations and feeder cables, together with associated substation protective devices, and may include supervisory control and data acquisition. -

Final Gold Line Report

STRATEGIC PLANNING STUDY REPORT FOR METRO GOLD LINE FOOTHILL EXTENSION TO LA/ONTARIO INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT PREPARED FOR Metro Gold Line Foothill Extension Construction Authority Funded By San Bernardino Associated Governments and The Southern California Association of Governments December 2008 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: Metro Gold Line Foothill Extension Construction Authority Southern California Association of Governments San Bernardino Associated Governments San Bernardino County Board of Supervisors Los Angeles World Airports PREPARED BY: KOA Corporation In Association with: STV Incorporated J.L. Patterson & Associates, INC. Consensus Planning Group, Inc. CITYWORKS DESIGN Metro Gold Line Foothill Extension to LA/Ontario International Airport Strategic Planning Study Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................... E-1 BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................................................................................. E-1 PLANNING TEAM APPROACH AND PUBLIC OUTREACH .......................................................................................................... E-1 THE ALIGNMENTS ........................................................................................................................................................................ E-2 ADDITIONAL STUDY CONSIDERATIONS ................................................................................................................................... -

Google Data Collection —NEW—

Digital Content Next January 2018 / DCN Distributed Content Revenue Benchmark Google Data Collection —NEW— August 2018 digitalcontentnext.org CONFIDENTIAL - DCN Participating Members Only 1 This research was conducted by Professor Douglas C. Schmidt, Professor of Computer Science at Vanderbilt University, and his team. DCN is grateful to support Professor Schmidt in distributing it. We offer it to the public with the permission of Professor Schmidt. Google Data Collection Professor Douglas C. Schmidt, Vanderbilt University August 15, 2018 I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. Google is the world’s largest digital advertising company.1 It also provides the #1 web browser,2 the #1 mobile platform,3 and the #1 search engine4 worldwide. Google’s video platform, email service, and map application have over 1 billion monthly active users each.5 Google utilizes the tremendous reach of its products to collect detailed information about people’s online and real-world behaviors, which it then uses to target them with paid advertising. Google’s revenues increase significantly as the targeting technology and data are refined. 2. Google collects user data in a variety of ways. The most obvious are “active,” with the user directly and consciously communicating information to Google, as for example by signing in to any of its widely used applications such as YouTube, Gmail, Search etc. Less obvious ways for Google to collect data are “passive” means, whereby an application is instrumented to gather information while it’s running, possibly without the user’s knowledge. Google’s passive data gathering methods arise from platforms (e.g. Android and Chrome), applications (e.g. -

Federal Pacific Electric (FPE) Stab-Lok Breakers and Panelboards

Federal Pacific Electric (FPE) Stab-Lok Breakers and Panelboards HSB, part of Munich Re, is a What is the best course of action when discovered? technology-driven company built on a foundation of specialty insurance, engineering and technology, all Federal Pacific Electric Company (FPE) manufactured many electrical products working together to drive innovation while in business including a panelboard and breaker line called Stab-Lok. The in a modern world. Stab-Lok products are no longer manufactured, but millions had been installed in residential and commercial buildings between 1950 and 1985. The purpose of the breaker is to protect the building from fire in the event of an electrical circuit abnormality. The Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) investigated many reports in 1982 of Stab-Lok breakers failing to trip as required by Underwriters Laboratories (UL) testing standards. The CPSC did not have the funding to further investigate this problem or arrive at a definitive conclusion. Tests by the CPSC and independent consulting engineers concluded that certain Stab-Lok breakers do not trip according to UL requirements and in some cases, can jam in the “on” position. In addition, overheating problems have been found within the panelboard internal bus connections. Unfortunately, this information surfaced after many Stab-Lokinstallations were completed and had been in service for years. In 2002, a New Jersey class-action lawsuit decided that the manufacturer of the Stab-Lok breakers committed fraud over many years in issuing UL labels to products they knew did not meet the UL testing requirements. HSB Page 2/2 Federal Pacific Electric (FPE) Stab-Lok Breakers and Panelboards The National Electrical Code requires that all installed products must be listed and labeled by an independent testing agency to be acceptable for the intended use. -

MCO Arrival Wayfnding Map

MCO Arrival Wayfnding Map N SIDE Gates 1-29 Level 1 Gates 100-129 Ground Transportation & Baggage Claim (8A) Level 2 Baggage Claim Gates 10-19 Gates Ticketing Locations 20-29 Gates 100-111 A-1 A-2 Level 3 A-3 A-4 2 1 Gates Gates 1-9 112-129 Hyatt Regency - Lvl.4 - Lvl.4 Regency Hyatt Security Checkpoint To Gates 70 - 129 70 Gates To Food Court To Gates 1-59 1-59 Gates To Security Checkpoint Gates 70-79 Gates 50-59 To Parking “C” Gates 3 90-99 4 B-1 B-2 Level 3 B-3 B-4 Gates Gates 30-39 Ticketing Locations Gates 80-89 40-49 Gates 70-99 Level 2 Gates 30-59 Baggage Claim Level 1 Ground Transportation & Baggage Claim (28B) SIDE C Check-in and baggage claim locations subject to change. Please check signage on arrival. *Map not to scale Find it ALL in One Place Welcome to Orlando Download the Orlando MCO App Available for International Airport (MCO) OrlandoAirports.net /flymco @MCO @flymco Flight Arrival Guide 03/18 To reach the Main Terminal, The journey to the To retrieve checked baggage, take follow directions on the overhead Main Terminal (A-Side or B-Side) the stairs, escalator or elevator down signage to the shuttle station 2 takes just over one minute. As the 4 6 to the Arrivals/Baggage Claim on which is located in the center train transports you, observe the Level 2. Check the monitors to of the Airside Terminal. signage and listen to the instructions determine the correct carousel directing you to either Baggage Claim A for your flight.