A Hep Kid with a Beat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ralph W. Judd Collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt487035r5 No online items Finding Aid to the Ralph W. Judd Collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts Michael P. Palmer Processing partially funded by generous grants from Jim Deeton and David Hensley. ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives 909 West Adams Boulevard Los Angeles, California 90007 Phone: (213) 741-0094 Fax: (213) 741-0220 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.onearchives.org © 2009 ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives. All rights reserved. Finding Aid to the Ralph W. Judd Coll2007-020 1 Collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts Finding Aid to the Ralph W. Judd Collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts Collection number: Coll2007-020 ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives Los Angeles, California Processed by: Michael P. Palmer, Jim Deeton, and David Hensley Date Completed: September 30, 2009 Encoded by: Michael P. Palmer Processing partially funded by generous grants from Jim Deeton and David Hensley. © 2009 ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Ralph W. Judd collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts Dates: 1848-circa 2000 Collection number: Coll2007-020 Creator: Judd, Ralph W., 1930-2007 Collection Size: 11 archive cartons + 2 archive half-cartons + 1 records box + 8 oversize boxes + 19 clamshell albums + 14 albums.(20 linear feet). Repository: ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives. Los Angeles, California 90007 Abstract: Materials collected by Ralph Judd relating to the history of cross-dressing in the performing arts. The collection is focused on popular music and vaudeville from the 1890s through the 1930s, and on film and television: it contains few materials on musical theater, non-musical theater, ballet, opera, or contemporary popular music. -

Selected Observations from the Harlem Jazz Scene By

SELECTED OBSERVATIONS FROM THE HARLEM JAZZ SCENE BY JONAH JONATHAN A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Jazz History and Research Written under the direction of Dr. Lewis Porter and approved by ______________________ ______________________ Newark, NJ May 2015 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements Page 3 Abstract Page 4 Preface Page 5 Chapter 1. A Brief History and Overview of Jazz in Harlem Page 6 Chapter 2. The Harlem Race Riots of 1935 and 1943 and their relationship to Jazz Page 11 Chapter 3. The Harlem Scene with Radam Schwartz Page 30 Chapter 4. Alex Layne's Life as a Harlem Jazz Musician Page 34 Chapter 5. Some Music from Harlem, 1941 Page 50 Chapter 6. The Decline of Jazz in Harlem Page 54 Appendix A historic list of Harlem night clubs Page 56 Works Cited Page 89 Bibliography Page 91 Discography Page 98 3 Acknowledgements This thesis is dedicated to all of my teachers and mentors throughout my life who helped me learn and grow in the world of jazz and jazz history. I'd like to thank these special people from before my enrollment at Rutgers: Andy Jaffe, Dave Demsey, Mulgrew Miller, Ron Carter, and Phil Schaap. I am grateful to Alex Layne and Radam Schwartz for their friendship and their willingness to share their interviews in this thesis. I would like to thank my family and loved ones including Victoria Holmberg, my son Lucas Jonathan, my parents Darius Jonathan and Carrie Bail, and my sisters Geneva Jonathan and Orelia Jonathan. -

Jazz and the Cultural Transformation of America in the 1920S

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s Courtney Patterson Carney Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Carney, Courtney Patterson, "Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 176. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/176 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. JAZZ AND THE CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICA IN THE 1920S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Courtney Patterson Carney B.A., Baylor University, 1996 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2003 For Big ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The real truth about it is no one gets it right The real truth about it is we’re all supposed to try1 Over the course of the last few years I have been in contact with a long list of people, many of whom have had some impact on this dissertation. At the University of Chicago, Deborah Gillaspie and Ray Gadke helped immensely by guiding me through the Chicago Jazz Archive. -

Louis Armstrong

A+ LOUIS ARMSTRONG 1. Chimes Blues (Joe “King” Oliver) 2:56 King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band: King Oliver, Louis Armstrong-co; Honore Dutrey-tb; Johnny Dodds-cl; Lil Hardin-p, arr; Arthur “Bud” Scott-bjo; ?Bill Johnson-b; Warren “Baby” Dodds-dr. Richmond, Indiana, April 5, 1923. first issue Gennett 5135/matrix number 11387-A. CD reissue Masters of Jazz MJCD 1. 2. Weather Bird Rag (Louis Armstrong) 2:45 same personnel. Richmond, Indiana, April 6, 1923. Gennett 5132/11388. Masters of Jazz MJCD 1. 3. Everybody Loves My Baby (Spencer Williams-Jack Palmer) 3:03 Fletcher Henderson and his Orchestra: Elmer Chambers, Howard Scott-tp; Louis Armstrong-co, vocal breaks; Charlie Green-tb; Buster Bailey, Don Redman, Coleman Hawkins-reeds; Fletcher Henderson-p; Charlie Dixon- bjo; Ralph Escudero-tu; Kaiser Marshall-dr. New York City, November 22-25, 1924. Domino 3444/5748-1. Masters of Jazz MJCD 21. 4. Big Butter and Egg Man from the West (Armstrong-Venable) 3:01 Louis Armstrong and his Hot Five: Louis Armstrong-co, voc; Edward “Kid” Ory-tb; Johnny Dodds-cl; Lil Hardin Armstrong-p; Johnny St. Cyr-bjo; May Alix-voc. Chicago, November 16, 1926. Okeh 8423/9892-A. Maze 0034. 5. Potato Head Blues (Armstrong) 2:59 Louis Armstrong and his Hot Seven: Louis Armstrong-co; John Thomas-tb; Johnny Dodds-cl; Lil Hardin Armstrong-p; Johnny St. Cyr-bjo; Pete Briggs-tu; Warren “Baby” Dodds-dr. Chicago, May 10, 1927. Okeh 8503/80855-C. Maze 0034. 6. Struttin’ with Some Barbecue (Armstrong) 3:05 Louis Armstrong and his Hot Five. -

Jacques Butler “Jack”

1 The TRUMPET of JACQUES BUTLER “JACK” Solographer: Jan Evensmo Last update: July 7, 2019 2 Born: April 29, 1909 Died: 2003 Introduction: There is no doubt: Jacques Butler was well known in the Norwegian jazz community, because he was visiting Oslo in 1940 and recorded one 78 rpm. together with our own best jazz performers. So, we grew up with him! History: Raised in Washington, D.C., studied dentistry at Howard University, began playing trumpet at the age of 17. Moved to New York City, worked with Cliff Jackson in the late 1920s, with Horace Henderson (1930-1). Led own band (in New York and on tour) 1934-35, worked with Willie Bryant, then to Europe. Joined Willie Lewis band (late 1936), worked mainly with Willie Lewis until 1939, then toured Scandinavia from June 1939. Was in Norway at the commencement of World War II, returned to the U.S.A. in April 1940. Led own band, worked with Mezz Mezzrow (spring 1943), with Art Hodes (summer 1943- 44), with Bingie Madison (1945), with bassist Cass Carr (summer 1947). Worked in Toronto, Canada (1948). Returned to Europe in late 1950, led own band on various tours, then played long residency at ‘La Cigale’, Paris, from 1953 until returning to the U.S.A. in 1968. Still plays regularly in New York (at the time of writing). Appeared in the film ‘Paris Blues’ (1961). (ref. John Chilton). 3 JACK BUTLER SOLOGRAPHY SAMMY LEWIS & HIS BAMVILLE SYNCOPATORS NYC. June 14, 1926 Edwin Swayze (cnt, arr), Jack Butler (cnt, cl?), Oscar Hammond (tb), Eugene Eikelberger (cl, as), Paul Serminole (p), Jimmy McLin (bjo), Lester Nichols (dm), Sammy Lewis (vo). -

What Is This Thing Called Swing? and Other Kinds of Jazz for That Matter?

What is This Thing Called Swing? And other kinds of jazz for that matter? What is This Thing Called Swing - Lunceford Key vocabulary • Meter, or time signature: This refers to the number of beats in one concise section of music. Although by no means a universal truth, in a basic and simple sense this usually means the number of beats per chord. Early jazz is typically in 2 (or 2/4 time) meaning 2 beats per unit, whereas later jazz becomes in 4 (4/4 time) with 4 beats per unit. This is mostly just a matter of conception of the basic unit and not a fundamental difference in how the music works. • Example in 2: 12th Street Rag - Kid Ory • Example in 4: Moten Swing - Benny Moten • Strong and Weak Beats: In any particular meter there is a set of beats that are accented and a set of beats that are not accented. In the music predating jazz, the strong beats are typically on the odd beats - 1 and 3 for example. • Beethoven - Sonata no. 8 in C minor • Sousa - Stars and Stripes Forever • In jazz, and almost all popular music to follow, the strong beat has been moved to the even beats. 2 and 4. This is why friends don’t let friends clap on 1 and 3. This quality is called the back beat. • Mills Blue Rhythm Band - Back Beats • The Beatles - Penny Lane • Syncopation: This term specifically refers to accents in the music that are not in the expected places. The back beat is one type of syncopation, other kinds are anticipations where the melodic line begins before the downbeat, or hesitations where the melodic line begins slightly delayed from the downbeat. -

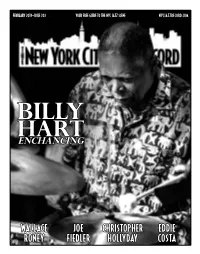

Wallace Roney Joe Fiedler Christopher

feBrUARY 2019—ISSUe 202 YOUr FREE GUide TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM BILLY HART ENCHANCING wallace joe christopher eddie roney fiedler hollyday costa Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East feBrUARY 2019—ISSUe 202 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 new york@niGht 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: interview : wallace roney 6 by anders griffen [email protected] Andrey Henkin: artist featUre : joe fiedler 7 by steven loewy [email protected] General Inquiries: on the cover : Billy hart 8 by jim motavalli [email protected] Advertising: encore : christopher hollyday 10 by robert bush [email protected] Calendar: lest we forGet : eddie costa 10 by mark keresman [email protected] VOXNews: LAbel spotliGht : astral spirits 11 by george grella [email protected] VOXNEWS by suzanne lorge US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or oBitUaries 12 by andrey henkin money order to the address above or email [email protected] FESTIVAL REPORT 13 Staff Writers Duck Baker, Stuart Broomer, Robert Bush, Kevin Canfield, CD reviews 14 Marco Cangiano, Thomas Conrad, Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Miscellany Tom Greenland, George Grella, 31 Anders Griffen, Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, event calendar Matthew Kassel, Mark Keresman, 32 Marilyn Lester, Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Jim Motavalli, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Scott Yanow Contributing Writers Brian Charette, Steven Loewy, As unpredictable as the flow of a jazz improvisation is the path that musicians ‘take’ (the verb Francesco Martinelli, Annie Murnighan, implies agency, which is sometimes not the case) during the course of a career. -

Howard Scott

THE RECORDINGS OF HOWARD SCOTT An Annotated Tentative Discography SCOTT, Howard born: c. 1900 Played with Shrimp Jones (late 1923); recorded with Fletcher Hendserson starting with Edison session (Nov. 1923), and played with Henderson from Jan. 1924 till Apr. 1925. With Bill Brown (fall 1925); Allie Ross (spring 1926); Joe? Wynne (Aug. 1927); Alex Jackson (early 1929); Lew Leslie show (1929-30); Kaiser Marshall (early 1932); possibly with Chick Webb (c. 1932); Benny Carter (late 1932); recorded with Spike Hughes (May 1933); James P. Johnson (1934). Frank Driggs met him first in fall of 1971; the last surviving member of Fl. Henderson´s first regular band, he is retired from a Civil Service job, reportedly is executive of the New Amsterdam Musical Association in Harlem, and still well and hearty! (W.C. Allen, Hendersonia, 1973) SCOTT, HOWARD STYLE Howard Scott has a habit of dropping pitch at the end of his notes and bending his notes downward to the consecutive notes, very similar to Louis Metcalf. Stylistically, he is a follower of Johnny Dunn´s kind of playing. Because of sufficient technical ability and expertize he is able to turn his style in the direction of his stronger colleagues in the Henderson band, Joe Smith and Louis Armstrong. This may have been the cause for Henderson to engage him from the Shrimp Jones band. It is interesting to recognize how Scott develops into a sincere hot soloist, beginning with some awkward old-fashioned 6/8 phrasing in session 001 to a respectable hot blues accompanist at later sessions. It really seems to be a blow of fate that he had to retain when Armastrong joined the band. -

The Great American Songbook in the Classical Voice Studio

THE GREAT AMERICAN SONGBOOK IN THE CLASSICAL VOICE STUDIO BY KATHERINE POLIT Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University May, 2014 Accepted by the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music. ___________________________________ Patricia Wise, Research Director and Chair __________________________________ Gary Arvin __________________________________ Raymond Fellman __________________________________ Marietta Simpson ii For My Grandmothers, Patricia Phillips and Leah Polit iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to express my sincerest thanks to the members of my committee—Professor Patricia Wise, Professor Gary Arvin, Professor Marietta Simpson and Professor Raymond Fellman—whose time and help on this project has been invaluable. I would like to especially thank Professor Wise for guiding me through my education at Indiana University. I am honored to have her as a teacher, mentor and friend. I am also grateful to Professor Arvin for helping me in variety of roles. He has been an exemplary vocal coach and mentor throughout my studies. I would like to give special thanks to Mary Ann Hart, who stepped in to help throughout my qualifying examinations, as well as Dr. Ayana Smith, who served as my minor field advisor. Finally, I would like to thank my family for their love and support throughout my many degrees. Your unwavering encouragement is the reason I have been -

Benny Goodman's Band As Opening C Fit Are Russell Smith, Joe Keyes, Miller Band Opened a Week Ago Bassist

orsey Launches Brain Trust! Four Bands, On the Cover Abe Most, the very fine fe« Three Chirps Brown clarinet man. just couldn't mm up ’he cornfield which uf- 608 S, Dearborn, Chicago, IK feted thi» wonderful opportunity Entered as «cwwrf Hom matter October 6.1939. at the poet oHice at Chicano. tllinou, under the Act of March 3, 1379. Copyright 1941 Taken Over for shucking. Lovely gal io Betty Bn Down Beat I’ubliAing Co., Ine. Janney, the Brown band'* chirp New York—With the open anil rumored fiancee of Most. ing of his penthouse offices Artene Pie- on Broadway and the estab VOL. 0. NO. 20 CHICAGO, OCTOBER 15, 1941 15 CENTS' lishment of his own personal management bureau, headed by Leonard Vannerson and Phil Borut, Tommy Dorsey JaeÆ Clint Brewer This Leader's Double Won Five Bucks becomes one of the most im portant figures in the band In Slash Murder business. Dorsey’s office has taken New York—The mutilated body of a mother of two chil- over Harry James’ band as Iren, found in a Harlem apartment house, sent police in nine well as the orks of Dean Hud lates on a search for Clinton P. Brewer last week. Brewer is son, Alex Bartha and Harold ihe Negro composer-arranger who was granted a parole from Aloma, leader of small “Hawaiian” style combo. In Addi the New Jersey State Penitentiary last summer after he com tion. Dorsey now is playing father posed and arranged Stampede in G-Minor, which Count to three music publishing houses, the Embassy, Seneca and Mohawk Ie’s band recorded. -

Jimmy Mchugh Collection of Sheet Music Title

Cal State LA Special Collections & Archives Jimmy McHugh Collection of Sheet Music Title: Jimmy McHugh Collection of Sheet Music Collection Number: 1989.001 Creator: Jimmy McHugh Music Inc Dates: 1894 - 1969 Extent: 8 linear ft. Repository: California State University, Los Angeles, John F. Kennedy Memorial Library, Special Collections and Archives Location: Special Collections & Archives, Palmer, 4th floor Room 4048 - A Provenance: Donated by Lucille Meyers. Processing Information: Processed by Jennifer McCrackan 2017 Arrangement: The collection is organized into three series: I. Musical and Movie Scores; II. Other Scores; III. Doucments; IV: LP Record. Copyright: Jimmy McHugh Musical Scores Collection is the physical property of California State University, Los Angeles, John F. Kennedy Memorial Library, Special Collections and Archives. Preferred Citation: Folder title, Series, Box number, Collection title, followed by Special Collections and Archives, John F. Kennedy Memorial Library, California State University, Los Angeles Historical/Biographical Note Jimmy Francis McHugh was born in Boston, Massachusetts on July 10th, 1893 and is hailed as one of the most popular Irish-American songwriters since Victor Herbert. His father was a plumber and his mother was an accomplished pianist. His career began when he was promoted from a office boy to a rehearsal pianist at the Boston Opera House. As his desire was to write and perform “popular” music, he left the job in 1917 to become a pianist and song plugger in Boston with the Irving Berlin publishing company. In 1921, he moved to New York after getting married and started working for Jack Mills Inc. where he published his first song, Emaline. -

Really the Blues, Mezzrow Says: “I Was the Only White Man in the Crowd

rom the time that Mezz Mezzrow first heard Sidney Bechet playing with the Original New Orleans Creole Jazz Band in Chicago in 1918, he nursed a burning ambition to record with him, inspired by the duets Bechet played with the band’s clarinettist Fleader, Lawrence Dewey. It took Mezzrow 20 years to realise that ambition, finally achieving his goal when French critic Hugues Panassié made his recording safari to New York in November 1938. The 12 tracks on this album are of later vintage, a selection from the sides that Mezzrow made in the mid-forties when he was president of the King Jazz record company. Recalling the Bechet dates in his celebrated autobiography, Really The Blues, Mezzrow says: “I was the only white man in the crowd. I walked on clouds all through those recording sessions… How easy it was, falling in with Bechet – what an instinctive mastery of harmony he has, and how marvellously delicate his ear is!” The Mezzrow-Bechet partnership was a conspicuously one-sided match because Mezzrow had nothing like Bechet’s stature as a musician. But he was undoubtedly a good catalyst for Bechet, for whom he had a boundless admiration, and he made no secret of his inability to measure up to Bechet’s almost overpowering virtuosity. Mezzrow once said of one of his sessions with Bechet: “I was ashamed of not being better than I was, to give him the support he deserved and the inspiration, too”. Mezzrow came in for more than his share of adverse criticism during his playing career, and certainly he was never more than a mediocre musician whose intonation was frequently wretched.