King Porter Stomp" and the Jazz Tradition* Jazz Historians Have Reinforced and Expanded Morton's Claim and Goodman's Testimony

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Original Dixieland Jazz Band & "Nick" Larocca of New Orleans, Creator

Jack "Papa" Laine (Sicilian native George Vitale), Leader of his famous Reliance Brass Military Marching Band of New Orleans. Nick LaRocca was a regular member from 1910 to 1916. Original Dixieland Jazz Band & "Nick" LaRocca of New Orleans, Creator of Jazz Original Dixieland Jazz Band Members Victor release of "Livery Stable Blues" 1917. Victor release of "Dixie Jass Band One-Step" 1917. Original Dixieland Jazz Band - A 1918 promotional postcard showing (from left), drummer Tony Sbarbaro (aka Tony Spargo), trombonist Edwin "Daddy" Edwards, cornetist Dominick James "Nick" LaRocca, clarinetist Larry Shields, and pianist Henry Ragas 1917 Nick LaRocca Bust Courtesy Nick LaRocca Cultural Arts Center in Salaparuta, Sicily Dominic James "Nick" LaRocca Jimmy LaRocca 1889-1961 Continuing the Tradition In 1917, under the leadership of Nick LaRocca, the Original Dixieland Jazz Band (ODJB) made the first jazz recording. This first and many to follow were instant sensational “Hits” that were inspirational and influential beyond imagination. The success of the ODJB recordings was immense and musicians worldwide changed instrumentation to emulate the sound and style they made famous. From 1917 to 1938 they recorded fifty-two 78’s that are still sold today on various CD compilations. (Click on the photo below for a printable 8 X 10.) On February 8, 2006 the Original Dixieland Jazz Band was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame for their 1917 recording of the “Darktown Strutter’s Ball.” The ODJB is back in full swing under the direction of the original leader’s son, Jimmy LaRocca, on trumpet and vocals, with a fine ensemble of New Orleans musicians. -

Victory and Sorrow: the Music & Life of Booker Little

ii VICTORY AND SORROW: THE MUSIC & LIFE OF BOOKER LITTLE by DYLAN LAGAMMA A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Jazz History & Research written under the direction of Henry Martin and approved by _________________________ _________________________ Newark, New Jersey October 2017 i ©2017 Dylan LaGamma ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION VICTORY AND SORROW: THE MUSICAL LIFE OF BOOKER LITTLE BY DYLAN LAGAMMA Dissertation Director: Henry Martin Booker Little, a masterful trumpeter and composer, passed away in 1961 at the age of twenty-three. Little's untimely death, and still yet extensive recording career,1 presents yet another example of early passing among innovative and influential trumpeters. Like Clifford Brown before him, Theodore “Fats” Navarro before him, Little's death left a gap the in jazz world as both a sophisticated technician and an inspiring composer. However, unlike his predecessors Little is hardly – if ever – mentioned in jazz texts and classrooms. His influence is all but non-existent except to those who have researched his work. More than likely he is the victim of too early a death: Brown passed away at twenty-five and Navarro, twenty-six. Bob Cranshaw, who is present on Little's first recording,2 remarks, “Nobody got a chance to really experience [him]...very few remember him because nobody got a chance to really hear him or see him.”3 Given this, and his later work with more avant-garde and dissonant harmonic/melodic structure as a writing partner with Eric Dolphy, it is no wonder that his remembered career has followed more the path of James P. -

Selected Observations from the Harlem Jazz Scene By

SELECTED OBSERVATIONS FROM THE HARLEM JAZZ SCENE BY JONAH JONATHAN A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Jazz History and Research Written under the direction of Dr. Lewis Porter and approved by ______________________ ______________________ Newark, NJ May 2015 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements Page 3 Abstract Page 4 Preface Page 5 Chapter 1. A Brief History and Overview of Jazz in Harlem Page 6 Chapter 2. The Harlem Race Riots of 1935 and 1943 and their relationship to Jazz Page 11 Chapter 3. The Harlem Scene with Radam Schwartz Page 30 Chapter 4. Alex Layne's Life as a Harlem Jazz Musician Page 34 Chapter 5. Some Music from Harlem, 1941 Page 50 Chapter 6. The Decline of Jazz in Harlem Page 54 Appendix A historic list of Harlem night clubs Page 56 Works Cited Page 89 Bibliography Page 91 Discography Page 98 3 Acknowledgements This thesis is dedicated to all of my teachers and mentors throughout my life who helped me learn and grow in the world of jazz and jazz history. I'd like to thank these special people from before my enrollment at Rutgers: Andy Jaffe, Dave Demsey, Mulgrew Miller, Ron Carter, and Phil Schaap. I am grateful to Alex Layne and Radam Schwartz for their friendship and their willingness to share their interviews in this thesis. I would like to thank my family and loved ones including Victoria Holmberg, my son Lucas Jonathan, my parents Darius Jonathan and Carrie Bail, and my sisters Geneva Jonathan and Orelia Jonathan. -

Jazz and the Cultural Transformation of America in the 1920S

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s Courtney Patterson Carney Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Carney, Courtney Patterson, "Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 176. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/176 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. JAZZ AND THE CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICA IN THE 1920S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Courtney Patterson Carney B.A., Baylor University, 1996 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2003 For Big ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The real truth about it is no one gets it right The real truth about it is we’re all supposed to try1 Over the course of the last few years I have been in contact with a long list of people, many of whom have had some impact on this dissertation. At the University of Chicago, Deborah Gillaspie and Ray Gadke helped immensely by guiding me through the Chicago Jazz Archive. -

Porgy and Bess Composer: George Gershwin Section of the Work to Be

Title: Porgy and Bess Composer: George Gershwin Section of the work to be studied: ‘Summertime’ Interpretation in performance 1: Leontyne Price, from 1:11 to 4:32, Porgy and Bess: High Performance, RCA Interpretation in performance 2: Billie Holiday, The Quintessential Billie Holiday, Vol. 2: 1936, Columbia, this recording is also available on a number of compilation CDs. Score: Summertime, single for voice and piano. Alfred Publishing. (AP.VS5985) The following notes are designed to inform discussion. They are not to be considered as representative of the VCAA or amuse. The notes are to be used as starting points. Paul Curtis 2009 Briefly: Gershwin completed the work in September 1935 following 20 months of work. The show opened on 30 September 1935 at Boston’s Colonial Theatre. The show opened in New York at the Alvin Theatre on 10 October. The show ran for only 124 shows at the Alvin. The critical reaction was mixed and the entire monetary investment was lost. Gershwin wrote the following defense of his work: It is true that I have written songs for Porgy and Bess. I am not ashamed at writing songs at any time so long as they are good songs. In Porgy and Bess I realized that I was writing an opera for the theatre and without songs it could be neither of the theatre nor entertaining from my viewpoint. But songs are entirely within the operatic tradition. Many of the most successful operas of the past have had songs….Of course, the songs in Porgy and Bess are only a part of the whole…I have used symphonic music to unify entire scenes. -

Louis Armstrong

A+ LOUIS ARMSTRONG 1. Chimes Blues (Joe “King” Oliver) 2:56 King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band: King Oliver, Louis Armstrong-co; Honore Dutrey-tb; Johnny Dodds-cl; Lil Hardin-p, arr; Arthur “Bud” Scott-bjo; ?Bill Johnson-b; Warren “Baby” Dodds-dr. Richmond, Indiana, April 5, 1923. first issue Gennett 5135/matrix number 11387-A. CD reissue Masters of Jazz MJCD 1. 2. Weather Bird Rag (Louis Armstrong) 2:45 same personnel. Richmond, Indiana, April 6, 1923. Gennett 5132/11388. Masters of Jazz MJCD 1. 3. Everybody Loves My Baby (Spencer Williams-Jack Palmer) 3:03 Fletcher Henderson and his Orchestra: Elmer Chambers, Howard Scott-tp; Louis Armstrong-co, vocal breaks; Charlie Green-tb; Buster Bailey, Don Redman, Coleman Hawkins-reeds; Fletcher Henderson-p; Charlie Dixon- bjo; Ralph Escudero-tu; Kaiser Marshall-dr. New York City, November 22-25, 1924. Domino 3444/5748-1. Masters of Jazz MJCD 21. 4. Big Butter and Egg Man from the West (Armstrong-Venable) 3:01 Louis Armstrong and his Hot Five: Louis Armstrong-co, voc; Edward “Kid” Ory-tb; Johnny Dodds-cl; Lil Hardin Armstrong-p; Johnny St. Cyr-bjo; May Alix-voc. Chicago, November 16, 1926. Okeh 8423/9892-A. Maze 0034. 5. Potato Head Blues (Armstrong) 2:59 Louis Armstrong and his Hot Seven: Louis Armstrong-co; John Thomas-tb; Johnny Dodds-cl; Lil Hardin Armstrong-p; Johnny St. Cyr-bjo; Pete Briggs-tu; Warren “Baby” Dodds-dr. Chicago, May 10, 1927. Okeh 8503/80855-C. Maze 0034. 6. Struttin’ with Some Barbecue (Armstrong) 3:05 Louis Armstrong and his Hot Five. -

Guide to the Martin Williams Collection

Columbia College Chicago Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago CBMR Collection Guides / Finding Aids Center for Black Music Research 2020 Guide to the Martin Williams Collection Columbia College Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colum.edu/cmbr_guides Part of the History Commons, and the Music Commons Columbia COLLEGE CHICAGO CENTER FOR BLACK MUSIC RESEARCH COLLECTION The Martin Williams Collection,1945-1992 EXTENT 7 boxes, 3 linear feet COLLECTION SUMMARY Mark Williams was a critic specializing in jazz and American popular culture and the collection includes published articles, unpublished manuscripts, files and correspondence, and music scores of jazz compositions. PROCESSING INFORMATION The collection was processed, and a finding aid created, in 2010. BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Martin Williams [1924-1992] was born in Richmond Virginia and educated at the University of Virginia (BA 1948), the University of Pennsylvania (MA 1950) and Columbia University. He was a nationally known critic, specializing in jazz and American popular culture. He wrote for major jazz periodicals, especially Down Beat, co-founded The Jazz Review and was the author of numerous books on jazz. His book The Jazz Tradition won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in music criticism in 1973. From 1971-1981 he directed the Jazz and American Culture Programs at the Smithsonian Institution, where he compiled two widely respected collections of recordings, The Smithsonian Collection of Classic Jazz, and The Smithsonian Collection of Big Band Jazz. His liner notes for the latter won a Grammy Award. SCOPE & CONTENT/COLLECTION DESCRIPTION Martin Williams preferred to retain his writings in their published form: there are many clipped articles but few manuscript drafts of published materials in his files. -

![The American Legion [Volume 120, No. 3 (March 1986)]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3408/the-american-legion-volume-120-no-3-march-1986-563408.webp)

The American Legion [Volume 120, No. 3 (March 1986)]

! IT IS NO U.S. MILITARY SECRET! fAVY You can't buy a better designed pair of shoes for Fit and Comfort and LAST While they last m I Long Wear than this world famous classic designed for and by the m GET 2 Pairs U.S. Navy! Now Haband, the mail order people from Paterson, NJ, far $55 SHOES IHI WM I have a huge surplus on hand and available to the general public — while they last — only $27.95 a pair! ^HABAND 265 N. 9th St., Paterson, N.J. 07530 Genuine Leather Uppers! Genuine Leather Sole! Aye Aye, Sir! Send me pairs of these Navy Last Shoes as specified below. ir Genuine Rubber Heel! Genuine Goodyear Welt Construction If you can act at once, here is the FIND YOUR SIZE HERE best shoe value you could see in *tAiirMr /irfrir\ ADD $1 PtR PAIR MEDIUM (D) WIDTH *WIDE (EEE) — FOR WIDE SIZtS lifetime ! At $27.95 a pair, 6y2-7-7y2-8-8y2-9-9y2 6y2-7-7y2-8-8y2-9-9y2 you can afford the 10-10y2-11-12-13 10-10y2-11-12-13 very best. Order on money-back STYLE — approval Black Oxford Mail this Black Loafer coupon today Black "Velcro®" Strap I Qluarantee: if upon receipt, I do not choose to wear the $ 2.40 shoes, I may return them within 30 days for a full refund 'wide width Size Charge of every penny I paid you. TOTAL PAYMENT ENCLOSED Or Charge: DVisa DMC Acct. # Exp. Date [ STATE ZIP HABAND is a conscientious family business, serving 9th Street I 265 N. -

Ernest Elliott

THE RECORDINGS OF ERNEST ELLIOTT An Annotated Tentative Name - Discography ELLIOTT, ‘Sticky’ Ernest: Born Booneville, Missouri, February 1893. Worked with Hank Duncan´s Band in Detroit (1919), moved to New York, worked with Johnny Dunn (1921), etc. Various recordings in the 1920s, including two sessions with Bessie Smith. With Cliff Jackson´s Trio at the Cabin Club, Astoria, New York (1940), with Sammy Stewart´s Band at Joyce´s Manor, New York (1944), in Willie ‘The Lion’ Smith´s Band (1947). Has retired from music, but continues to live in New York.” (J. Chilton, Who´s Who of Jazz) STYLISTICS Ernest Elliott seems to be a relict out of archaic jazz times. But he did not spend these early years in New Orleans or touring the South, but he became known playing in Detroit, changing over to New York in the very early 1920s. Thus, his stylistic background is completely different from all those New Orleans players, and has to be estimated in a different way. Bushell in his book “Jazz from the Beginning” says about him: “Those guys had a style of clarinet playing that´s been forgotten. Ernest Elliott had it, Jimmy O´Bryant had it, and Johnny Dodds had it.” TONE Elliott owns a strong, rather sharp, tone on the clarinet. There are instances where I feel tempted to hear Bechet-like qualities in his playing, probably mainly because of the tone. This quality might have caused Clarence Williams to use Elliott when Bechet was not available? He does not hit his notes head-on, but he approaches them with a fast upward slur or smear, and even finishes them mostly with a little downward slur/smear, making his notes to sound sour. -

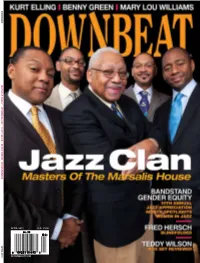

Downbeat.Com April 2011 U.K. £3.50

£3.50 £3.50 U.K. PRIL 2011 DOWNBEAT.COM A D OW N B E AT MARSALIS FAMILY // WOMEN IN JAZZ // KURT ELLING // BENNY GREEN // BRASS SCHOOL APRIL 2011 APRIL 2011 VOLume 78 – NumbeR 4 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Ed Enright Associate Editor Aaron Cohen Art Director Ara Tirado Production Associate Andy Williams Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Associate Maureen Flaherty ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Classified Advertising Sales Sue Mahal 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, John McDonough, Howard Mandel Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Michael Point, Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Robert Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, -

Tommy Dorsey 1 9

Glenn Miller Archives TOMMY DORSEY 1 9 3 7 Prepared by: DENNIS M. SPRAGG CHRONOLOGY Part 1 - Chapter 3 Updated February 10, 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS January 1937 ................................................................................................................. 3 February 1937 .............................................................................................................. 22 March 1937 .................................................................................................................. 34 April 1937 ..................................................................................................................... 53 May 1937 ...................................................................................................................... 68 June 1937 ..................................................................................................................... 85 July 1937 ...................................................................................................................... 95 August 1937 ............................................................................................................... 111 September 1937 ......................................................................................................... 122 October 1937 ............................................................................................................. 138 November 1937 ......................................................................................................... -

The Recordings

Appendix: The Recordings These are the URLs of the original locations where I found the recordings used in this book. Those without a URL came from a cassette tape, LP or CD in my personal collection, or from now-defunct YouTube or Grooveshark web pages. I had many of the other recordings in my collection already, but searched for online sources to allow the reader to hear what I heard when writing the book. Naturally, these posted “videos” will disappear over time, although most of them then re- appear six months or a year later with a new URL. If you can’t find an alternate location, send me an e-mail and let me know. In the meantime, I have provided low-level mp3 files of the tracks that are not available or that I have modified in pitch or speed in private listening vaults where they can be heard. This way, the entire book can be verified by listening to the same re- cordings and works that I heard. For locations of these private sound vaults, please e-mail me and I will send you the links. They are not to be shared or downloaded, and the selections therein are only identified by their numbers from the complete list given below. Chapter I: 0001. Maple Leaf Rag (Joplin)/Scott Joplin, piano roll (1916) listen at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9E5iehuiYdQ 0002. Charleston Rag (a.k.a. Echoes of Africa)(Blake)/Eubie Blake, piano (1969) listen at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R7oQfRGUOnU 0003. Stars and Stripes Forever (John Philip Sousa, arr.