Chapter Outline

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Record Series 1121-105, W. W. Law Music Collection Album Artwork

Record Series 1121‐105, W. W. Law Music Collection Album Artwork Inventory Alphabetically by Title Title Genre Box # / Folder #Associated with Box # / Folder # A Lincoln Portrait Music for the stage 1121‐105‐0043/FF04 1121‐105‐0029/FF2 A Nation Is Born; A Historic Vote For A Jewish State Narrative recordings‐‐ Addresses (speeches) 1121‐105‐0035/FF01 1121‐105‐0031/FF1 A Porter's Love Song/Since I've Been With You Jazz 1121‐105‐0037/FF08 1121‐105‐0005/FF4 American Spirituals Sacred music‐‐ Spirituals (songs) 1121‐105‐0035/FF03 1121‐105‐0022/FF12 Baby Daddy/Joogie Boogie Jazz 1121‐105‐0036/FF07 1121‐105‐0002/FF8 Ballad For Americans Classical music‐‐ Cantatas 1121‐105‐0036/FF01 1121‐105‐0007/FF7 Blues by Basie Blues (music) 1121‐105‐0037/FF03 1121‐105‐0033/FF9 Brahms Concerto No. 2, in B Flat Major, Op. 83 Classical music‐‐ Concertos 1121‐105‐0039/FF05 1121‐105‐0019/FF2 Brahms Symphony No. 3 In F, Op. 90 Classical Music‐‐Symphonies 1121‐105‐0040/FF04 1121‐105‐0019/FF1 Classical Music‐‐Symphonies 1121‐105‐0041/FF06 1121‐105‐0018/FF1 Cantorial Jewels Saturday, April 02, 2016 Page 1 of 6 Title Genre Box # / Folder #Associated with Box # / Folder # Sacred music 1121‐105‐0043/FF01 1121‐105‐0024/FF1 Concerto in C; (In The Style of Vivaldi) Classical music‐‐ Concertos 1121‐105‐0040/FF03 1121‐105‐0021/FF3 Concerto in D Major for Violin and Orcestra, Op. 77 Classical music‐‐ Concertos 1121‐105‐0042/FF02 1121‐105‐0009/FF1 Concerto in D Major for Violin and Orchestra, Op. -

CATALOGUE WELCOME to NAXOS JAZZ LEGENDS and NAXOS NOSTALGIA, Twin Compendiums Presenting the Best in Vintage Popular Music

NAXOS JAZZ LEGENDS/NOSTALGIA CATALOGUE WELCOME TO NAXOS JAZZ LEGENDS AND NAXOS NOSTALGIA, twin compendiums presenting the best in vintage popular music. Following in the footsteps of Naxos Historical, with its wealth of classical recordings from the golden age of the gramophone, these two upbeat labels put the stars of yesteryear back into the spotlight through glorious new restorations that capture their true essence as never before. NAXOS JAZZ LEGENDS documents the most vibrant period in the history of jazz, from the swinging ’20s to the innovative ’40s. Boasting a formidable roster of artists who forever changed the face of jazz, Naxos Jazz Legends focuses on the true giants of jazz, from the fathers of the early styles, to the queens of jazz vocalists and the great innovators of the 1940s and 1950s. NAXOS NOSTALGIA presents a similarly stunning line-up of all-time greats from the golden age of popular entertainment. Featuring the biggest stars of stage and screen performing some of the best- loved hits from the first half of the 20th century, this is a real treasure trove for fans to explore. RESTORING THE STARS OF THE PAST TO THEIR FORMER GLORY, by transforming old 78 rpm recordings into bright-sounding CDs, is an intricate task performed for Naxos by leading specialist producer-engineers using state-of-the-art-equipment. With vast personal collections at their disposal, as well as access to private and institutional libraries, they ensure that only the best available resources are used. The records are first cleaned using special equipment, carefully centred on a heavy-duty turntable, checked for the correct playing speed (often not 78 rpm), then played with the appropriate size of precision stylus. -

Selected Observations from the Harlem Jazz Scene By

SELECTED OBSERVATIONS FROM THE HARLEM JAZZ SCENE BY JONAH JONATHAN A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Jazz History and Research Written under the direction of Dr. Lewis Porter and approved by ______________________ ______________________ Newark, NJ May 2015 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements Page 3 Abstract Page 4 Preface Page 5 Chapter 1. A Brief History and Overview of Jazz in Harlem Page 6 Chapter 2. The Harlem Race Riots of 1935 and 1943 and their relationship to Jazz Page 11 Chapter 3. The Harlem Scene with Radam Schwartz Page 30 Chapter 4. Alex Layne's Life as a Harlem Jazz Musician Page 34 Chapter 5. Some Music from Harlem, 1941 Page 50 Chapter 6. The Decline of Jazz in Harlem Page 54 Appendix A historic list of Harlem night clubs Page 56 Works Cited Page 89 Bibliography Page 91 Discography Page 98 3 Acknowledgements This thesis is dedicated to all of my teachers and mentors throughout my life who helped me learn and grow in the world of jazz and jazz history. I'd like to thank these special people from before my enrollment at Rutgers: Andy Jaffe, Dave Demsey, Mulgrew Miller, Ron Carter, and Phil Schaap. I am grateful to Alex Layne and Radam Schwartz for their friendship and their willingness to share their interviews in this thesis. I would like to thank my family and loved ones including Victoria Holmberg, my son Lucas Jonathan, my parents Darius Jonathan and Carrie Bail, and my sisters Geneva Jonathan and Orelia Jonathan. -

Dear Friends, in Keeping with the Nostalgic Themes with Which We

Dear friends, In keeping with the nostalgic themes with which we normally open these Activity Pages, I thought I’d tell you a story about young love – its excitement, its promise, and its almost inevitable woes. It’s a true story, one from my own past. And it begins at Roller City, a roller skating rink located, in those distant days, on Alameda Avenue just west of Federal Boulevard in Denver, Colorado. It was a balmy Friday night when I first spied my Cinderella – a lovely, lithe thing with a cute smile, pink ribbons in her blonde hair, and very “girly” bons bons of matching color hanging on the front of her white roller skates. It might have been love at first sight but certainly by the time we skated hand in hand under the multi-colored lights in a romantic “couples skate,” I was a goner. Indeed, I fell more madly in love than I had at any other time in my whole life. I was 10 years old. I drop in that fact because it proved to be the relevant point in the impending tragedy of unrequited love. For you see, it turned out there was an unbridgeable gap in our ages. I was just getting ready to go into the 4th grade whereas I learned she was going into the 5th grade! Yipes! I had fallen for an older woman! How could I break it to her? And how would I deal with the rejection I knew must follow? I was in a terrible jam and so…and I’m not proud of it…I made up a lie. -

Jazz and the Cultural Transformation of America in the 1920S

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s Courtney Patterson Carney Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Carney, Courtney Patterson, "Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 176. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/176 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. JAZZ AND THE CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICA IN THE 1920S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Courtney Patterson Carney B.A., Baylor University, 1996 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2003 For Big ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The real truth about it is no one gets it right The real truth about it is we’re all supposed to try1 Over the course of the last few years I have been in contact with a long list of people, many of whom have had some impact on this dissertation. At the University of Chicago, Deborah Gillaspie and Ray Gadke helped immensely by guiding me through the Chicago Jazz Archive. -

Jazzletter P-Q Ocrober 1986 P 5Jno;..1O

Jazzletter P-Q ocrober 1986 P 5jNo;..1o . u-1'!-an J.R. Davis,.Bill Davis, Rusty Dedrick, Buddy DeFranco, Blair The Readers . Deiermann, Rene de Knight,‘ Ron Della Chiesa (WGBH), As of August 25, I986, the JazzIetrer’s readers were: Louise Dennys, Joe Derise, Vince Dellosa, Roger DeShon, Michael Abene, John Abbott, Mariano F. Accardi, Harlan John Dever, Harvey Diamond, Samuel H. Dibert’, Richard Adamcik, Keith Albano, Howard Alden, Eleanore Aldrich, DiCarlo, Gene DiNovi, Victor DiNovi, Chuck Domanico, Jeff Alexander, Steve Allen, Vernon Alley, Alternate and Arthur Domaschenz, Mr. and Mrs. Steve Donahue, William E. Independent Study Program, Bill Angel, Alfred Appel J r, Ted Donoghue, Bob Dorough, Ed Dougherty, Hermie Dressel, Len Arenson, Bruce R. Armstrong, Jim Armstrong, Tex Arnold, Dresslar, Kenny Drew, Ray Drummond, R.H. Duffield, Lloyd Kenny Ascher, George Avakian, Heman B. Averill, L. Dulbecco, Larry Dunlap, Marilyn Dunlap, Brian Duran, Jean Bach, Bob Bain, Charles Baker (Kent State University Eddie Duran, Mike Dutton (KCBX), ' School of Music), Bill Ballentine, Whitney Balliett, Julius Wendell Echols, Harry (Sweets) Edison,Jim_Eigo, Rachel Banas, Jim Barker, Robert H. Barnes, Charlie Barnet, Shira Elkind-Tourre, Jack Elliott, Herb Ellis, Jim Ellison, Jack r Barnett, Jeff Barr, E.M. Barto Jr, Randolph Bean, Jack Ellsworth (WLIM), Matt Elmore (KCBX FM), Gene Elzy Beckerman, Bruce B. Bee, Lori Bell, Malcolm Bell Jr, Carroll J . (WJR), Ralph Enriquez, Dewey Emey, Ricardo Estaban, Ray Bellis MD, Mr and Mrs Mike Benedict, Myron Bennett, Dick Eubanks (Capital University Conservatory of Music), Gil Bentley, Stephen C. Berens MD, Alan Bergman, James L. Evans, Prof Tom Everett (Harvard University), Berkowitz, Sheldon L. -

Indices for Alley Sing-A-Long Books

INDICES FOR ALLEY SING-A-LONG BOOKS Combined Table of Contents Places Index Songs for Multiple Singers People Index Film and Show Index Year Index INDICES FOR THE UNOFFICIAL ALLEY SING-A-LONG BOOKS Acknowledgments: Indices created by: Tony Lewis Explanation of Abbreviations (w) “words by” (P) “Popularized by” (CR) "Cover Record" i.e., a (m) “music by” (R) “Rerecorded by” competing record made of the same (wm) “words and music by” (RR) “Revival Recording” song shortly after the original record (I) “Introduced by” (usually the first has been issued record) NARAS Award Winner –Grammy Award These indices can be downloaded from http://www.exelana.com/Alley/TheAlley-Indices.pdf Best Is Yet to Come, The ............................................. 1-6 4 Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea .................. 2-6 nd Bewitched .................................................................... 1-7 42 Street (see Forty-Second Street) ........................ 2-20 Beyond the Sea ............................................................ 2-7 Bicycle Built for Two (see Daisy Bell) ..................... 2-15 A Big Spender ................................................................. 2-6 Bill ............................................................................... 1-7 A, You’re Adorable (The Alphabet Song) .................. 1-1 Bill Bailey, Won’t You Please Come Home ............... 1-8 Aba Daba Honeymoon, The ........................................ 1-1 Black Coffee ............................................................... -

The English Listing

THE CROSBY 78's ZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBAthe English listing Members may recall that we issued a THE questionnaire in 1990 seeking views and comments on what we should be providing in CROSBY BING. We are progressively attempting to fulfil 7 8 's these wishes and we now address one major ENGLISH request - a listing of the 78s issued in the UK. LISTING The first time this listing was issued in this form was in the ICC's 1974 booklet and this was updated in 1982in a publication issued by John Bassett's Crosby Collectors Society. The joint compilers were Jim Hayes, Colin Pugh and Bert Bishop. John has kindly given us permission to reproduce part of his publication in BING. This is a complete listing of very English-issued lO-inch and 12-inch 78 rpm shellac record featuring Sing Crosby. In all there are 601 discs on 10different labels. The sheet music used to illustrate some of the titles and the photos of the record labels have been p ro v id e d b y Don and Peter Haizeldon to whom we extend grateful thanks. NUMBERSITITLES LISTING OF ENGLISH 78"s ARIEl GRAND RECORD. THE 110-Inchl 4364 Susiannainon-Bing BRUNSWICK 112-inchl 1 0 5 Gems from "George White's Scandals", Parts 1 & 2 0 1 0 5 ditto 1 0 7 Lawd, you made the night too long/non-Bing 0 1 0 7 ditto 1 1 6 S I. L o u is blues/non-Bing _ 0 1 3 4 Pennies from heaven medley/Pennies from heaven THECROSBYCOLLECTORSSOCIETY BRUNSWICK 110-inchl 1 1 5 5 Just one more chance/Were you sincere? 0 1 6 0 8 Home on the range/The last round-up 0 1 1 5 5 ditto 0 1 6 1 5 Shadow waltz/I've got to sing a torch -

Rhythm Section Roles (In Standard Swing)

Rhythm Section Roles (in standard swing) ● Bass: Provide a solid metric and harmonic foundation by creating a quarter-note based melody with the roots and/or fifths of each chord occurring on downbeats and chord changes. ○ Ideal sound is plucked upright bass. Proper attack of note in right hand, clarity of center and sustain in left hand are key. ○ Create walking bassline by starting on root of chord and approaching subsequent roots or fifths by V-I resolution, half-step, or logical diatonic/chromatic motion or sequence. ● Drums: Assist bass in providing solid metric foundation, provide subdivision and stylistic emphasis, and drive dynamics and phrasing. ○ Right Hand: Primary responsibility is ride cymbal playing ride pattern. ■ Fundamental of ride pattern is quarter-notes with eighth-note subdivision added as desired, needed, and appropriate for dictation of swing. ■ Think of playing approximately ½” through cymbal to provide clarity and emphasis. ○ Left Foot: Play hi-hat on beats 2 and 4 for emphasis of fundamental syncopation. ■ Keep heel off the ground. ■ Cymbals should be approx. 1” apart. ○ Left Hand: Free to provide stylistic emphasis. ■ Cross-stick hits on beat 4 with bead of stick on drum head and shaft of stick striking rim of snare. ■ Musically logical “fills” on snare, toms, etc. to emphasize or set-up written figures or improvised solo moments. ○ Right Foot: Play bass drum. ■ Optionally “feather” bass drum as quarter notes to emphasize bassline by lightly hitting bass drum. Felt not heard, should not be louder than bass. ■ Use to emphasize ends of fills and set-up syncopation by playing downbeat before a syncopated entrance. -

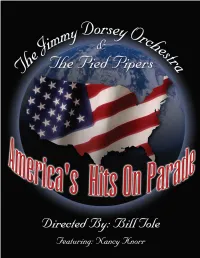

Jimmy Dorsey Orchestratm Jimmy’S Musical Training Began When He Was a Young Boy in Pennsylvania

America’s Music On Parade Enjoy an evening of America’s Hits that inspired many of the greatest recordings ever made. A memory of these songs touched our deepest feelings in a way no other songs have or ever will. American’s Hits On Parade are legendary songs from the most thrilling era of music that captured our hearts during an amazing ten years of music and history. The America’s Hits On Parade was everywhere! Radio’s broadcasted from ballrooms like the Aragon, Palomar, Palladium and the “Make Believe” Ballroom. Juke Boxes whirled at home while a world away GI’s warmly welcomed the sounds of America’s Hits. We danced at night clubs, USO’s, ballrooms and truly had the greatest time of our lives. Sit back and enjoy America’s Hits On Parade with an evening of the songs we cherished the most and will never forget listening to - I’ll Never Smile Again - In The Mood - I’m Getting Sentimental Over You - Tangerine - There Are Such Things - Dream - Boogie Woogie - So Rare - Stardust………. and many more. Jimmy Dorsey OrchestraTM Jimmy’s musical training began when he was a young boy in Pennsylvania. Along with his brother Tommy, the talented young musicians joined Paul Whiteman’s Orchestra and at the same time they were recording many records under the billing “The Dorsey Brothers Orchestra”. Their band continued through the early thirties until a dispute over a tempo of a song separated the brothers for decades. Jimmy found himself an instant leader of the band that became the birth of the Jimmy Dorsey Orchestra. -

Why Am I Doing This?

LISTEN TO ME, BABY BOB DYLAN 2008 by Olof Björner A SUMMARY OF RECORDING & CONCERT ACTIVITIES, NEW RELEASES, RECORDINGS & BOOKS. © 2011 by Olof Björner All Rights Reserved. This text may be reproduced, re-transmitted, redistributed and otherwise propagated at will, provided that this notice remains intact and in place. Listen To Me, Baby — Bob Dylan 2008 page 2 of 133 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................................................. 4 2 2008 AT A GLANCE ............................................................................................................................................................. 4 3 THE 2008 CALENDAR ......................................................................................................................................................... 5 4 NEW RELEASES AND RECORDINGS ............................................................................................................................. 7 4.1 BOB DYLAN TRANSMISSIONS ............................................................................................................................................... 7 4.2 BOB DYLAN RE-TRANSMISSIONS ......................................................................................................................................... 7 4.3 BOB DYLAN LIVE TRANSMISSIONS ..................................................................................................................................... -

1715 Total Tracks Length: 87:21:49 Total Tracks Size: 10.8 GB

Total tracks number: 1715 Total tracks length: 87:21:49 Total tracks size: 10.8 GB # Artist Title Length 01 Adam Brand Good Friends 03:38 02 Adam Harvey God Made Beer 03:46 03 Al Dexter Guitar Polka 02:42 04 Al Dexter I'm Losing My Mind Over You 02:46 05 Al Dexter & His Troopers Pistol Packin' Mama 02:45 06 Alabama Dixie Land Delight 05:17 07 Alabama Down Home 03:23 08 Alabama Feels So Right 03:34 09 Alabama For The Record - Why Lady Why 04:06 10 Alabama Forever's As Far As I'll Go 03:29 11 Alabama Forty Hour Week 03:18 12 Alabama Happy Birthday Jesus 03:04 13 Alabama High Cotton 02:58 14 Alabama If You're Gonna Play In Texas 03:19 15 Alabama I'm In A Hurry 02:47 16 Alabama Love In the First Degree 03:13 17 Alabama Mountain Music 03:59 18 Alabama My Home's In Alabama 04:17 19 Alabama Old Flame 03:00 20 Alabama Tennessee River 02:58 21 Alabama The Closer You Get 03:30 22 Alan Jackson Between The Devil And Me 03:17 23 Alan Jackson Don't Rock The Jukebox 02:49 24 Alan Jackson Drive - 07 - Designated Drinke 03:48 25 Alan Jackson Drive 04:00 26 Alan Jackson Gone Country 04:11 27 Alan Jackson Here in the Real World 03:35 28 Alan Jackson I'd Love You All Over Again 03:08 29 Alan Jackson I'll Try 03:04 30 Alan Jackson Little Bitty 02:35 31 Alan Jackson She's Got The Rhythm (And I Go 02:22 32 Alan Jackson Tall Tall Trees 02:28 33 Alan Jackson That'd Be Alright 03:36 34 Allan Jackson Whos Cheatin Who 04:52 35 Alvie Self Rain Dance 01:51 36 Amber Lawrence Good Girls 03:17 37 Amos Morris Home 03:40 38 Anne Kirkpatrick Travellin' Still, Always Will 03:28 39 Anne Murray Could I Have This Dance 03:11 40 Anne Murray He Thinks I Still Care 02:49 41 Anne Murray There Goes My Everything 03:22 42 Asleep At The Wheel Choo Choo Ch' Boogie 02:55 43 B.J.