Dorothy Fields and the American Musical

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Smile — Dancing Is About the Relationship

Smile — Dancing Is About the Relationship by Harold & Meredith Sears When we first learn a new figure, a new amalgamation, a new dance, it is natural to focus on the steps and the figures? But if we want to feel good and look good, we need to go beyond technical accuracy and incorporate into our dancing a relationship with our partner. Without a relationship, the dance is just steps, just exercise, just earnest, unsmiling locomotion. But if the dance contains emotion and communication, then we have something more than exercise. We have art. Of course, we need to execute the steps, but the steps only make up the foundation of a dance. Built on top of the steps, we need to feel the fun, the story that the dance might be telling, or the picture that it’s painting. If we can show that we enjoy our partner, if we can play off our partner and respond emotionally to the music and to the movements of the dance, then we can achieve a richness that goes well beyond the dance routine. Fred and Ginger — Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers made ten movies in all, nine between 1933 and 1939 and then a tenth, in 1949, almost by accident (Judy Garland was originally cast for the part). Of course, Fred and Ginger dance beautifully, but the beauty emerges especially because those dances are more than their steps. Many are wonderfully fun. Some are serious and dramatic, and some are even tragic. Their dances are physically and emotionally rich. Each dance embodies a human relationship. -

Ralph W. Judd Collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt487035r5 No online items Finding Aid to the Ralph W. Judd Collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts Michael P. Palmer Processing partially funded by generous grants from Jim Deeton and David Hensley. ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives 909 West Adams Boulevard Los Angeles, California 90007 Phone: (213) 741-0094 Fax: (213) 741-0220 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.onearchives.org © 2009 ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives. All rights reserved. Finding Aid to the Ralph W. Judd Coll2007-020 1 Collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts Finding Aid to the Ralph W. Judd Collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts Collection number: Coll2007-020 ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives Los Angeles, California Processed by: Michael P. Palmer, Jim Deeton, and David Hensley Date Completed: September 30, 2009 Encoded by: Michael P. Palmer Processing partially funded by generous grants from Jim Deeton and David Hensley. © 2009 ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Ralph W. Judd collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts Dates: 1848-circa 2000 Collection number: Coll2007-020 Creator: Judd, Ralph W., 1930-2007 Collection Size: 11 archive cartons + 2 archive half-cartons + 1 records box + 8 oversize boxes + 19 clamshell albums + 14 albums.(20 linear feet). Repository: ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives. Los Angeles, California 90007 Abstract: Materials collected by Ralph Judd relating to the history of cross-dressing in the performing arts. The collection is focused on popular music and vaudeville from the 1890s through the 1930s, and on film and television: it contains few materials on musical theater, non-musical theater, ballet, opera, or contemporary popular music. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Doing the Time Warp: Queer Temporalities and Musical Theater Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1k1860wx Author Ellis, Sarah Taylor Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Doing the Time Warp: Queer Temporalities and Musical Theater A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Theater and Performance Studies by Sarah Taylor Ellis 2013 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Doing the Time Warp: Queer Temporalities and Musical Theater by Sarah Taylor Ellis Doctor of Philosophy in Theater and Performance Studies University of California, Los Angeles, 2013 Professor Sue-Ellen Case, Co-chair Professor Raymond Knapp, Co-chair This dissertation explores queer processes of identification with the genre of musical theater. I examine how song and dance – sites of aesthetic difference within the musical – can warp time and enable marginalized and semi-marginalized fans to imagine different ways of being in the world. Musical numbers can complicate a linear, developmental plot by accelerating and decelerating time, foregrounding repetition and circularity, bringing the past to life and projecting into the future, and physicalizing dreams in a narratively open present. These excesses have the potential to contest naturalized constructions of historical, progressive time, as well as concordant constructions of gender, sexual, and racial identities. While the musical has historically been a rich source of identification for the stereotypical white gay male show queen, this project validates a broad and flexible range of non-normative readings. -

Lister); an American Folk Rhapsody Deutschmeister Kapelle/JULIUS HERRMANN; Band of the Welsh Guards/Cap

Guild GmbH Guild -Light Catalogue Bärenholzstrasse 8, 8537 Nussbaumen, Switzerland Tel: +41 52 742 85 00 - e-mail: [email protected] CD-No. Title Track/Composer Artists GLCD 5101 An Introduction Gateway To The West (Farnon); Going For A Ride (Torch); With A Song In My Heart QUEEN'S HALL LIGHT ORCHESTRA/ROBERT FARNON; SIDNEY TORCH AND (Rodgers, Hart); Heykens' Serenade (Heykens, arr. Goodwin); Martinique (Warren); HIS ORCHESTRA; ANDRE KOSTELANETZ & HIS ORCHESTRA; RON GOODWIN Skyscraper Fantasy (Phillips); Dance Of The Spanish Onion (Rose); Out Of This & HIS ORCHESTRA; RAY MARTIN & HIS ORCHESTRA; CHARLES WILLIAMS & World - theme from the film (Arlen, Mercer); Paris To Piccadilly (Busby, Hurran); HIS CONCERT ORCHESTRA; DAVID ROSE & HIS ORCHESTRA; MANTOVANI & Festive Days (Ancliffe); Ha'penny Breeze - theme from the film (Green); Tropical HIS ORCHESTRA; L'ORCHESTRE DEVEREAUX/GEORGES DEVEREAUX; (Gould); Puffin' Billy (White); First Rhapsody (Melachrino); Fantasie Impromptu in C LONDON PROMENADE ORCHESTRA/ WALTER COLLINS; PHILIP GREEN & HIS Sharp Minor (Chopin, arr. Farnon); London Bridge March (Coates); Mock Turtles ORCHESTRA; MORTON GOULD & HIS ORCHESTRA; DANISH STATE RADIO (Morley); To A Wild Rose (MacDowell, arr. Peter Yorke); Plink, Plank, Plunk! ORCHESTRA/HUBERT CLIFFORD; MELACHRINO ORCHESTRA/GEORGE (Anderson); Jamaican Rhumba (Benjamin, arr. Percy Faith); Vision in Velvet MELACHRINO; KINGSWAY SO/CAMARATA; NEW LIGHT SYMPHONY (Duncan); Grand Canyon (van der Linden); Dancing Princess (Hart, Layman, arr. ORCHESTRA/JOSEPH LEWIS; QUEEN'S HALL LIGHT ORCHESTRA/ROBERT Young); Dainty Lady (Peter); Bandstand ('Frescoes' Suite) (Haydn Wood) FARNON; PETER YORKE & HIS CONCERT ORCHESTRA; LEROY ANDERSON & HIS 'POPS' CONCERT ORCHESTRA; PERCY FAITH & HIS ORCHESTRA; NEW CONCERT ORCHESTRA/JACK LEON; DOLF VAN DER LINDEN & HIS METROPOLE ORCHESTRA; FRANK CHACKSFIELD & HIS ORCHESTRA; REGINALD KING & HIS LIGHT ORCHESTRA; NEW CONCERT ORCHESTRA/SERGE KRISH GLCD 5102 1940's Music In The Air (Lloyd, arr. -

Cole Porter: the Social Significance of Selected Love Lyrics of the 1930S

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Unisa Institutional Repository Cole Porter: the social significance of selected love lyrics of the 1930s by MARILYN JUNE HOLLOWAY submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the subject of ENGLISH at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR IA RABINOWITZ November 2010 DECLARATION i SUMMARY This dissertation examines selected love lyrics composed during the 1930s by Cole Porter, whose witty and urbane music epitomized the Golden era of American light music. These lyrics present an interesting paradox – a man who longed for his music to be accepted by the American public, yet remained indifferent to the social mores of the time. Porter offered trenchant social commentary aimed at a society restricted by social taboos and cultural conventions. The argument develops systematically through a chronological and contextual study of the influences of people and events on a man and his music. The prosodic intonation and imagistic texture of the lyrics demonstrate an intimate correlation between personality and composition which, in turn, is supported by the biographical content. KEY WORDS: Broadway, Cole Porter, early Hollywood musicals, gays and musicals, innuendo, musical comedy, social taboos, song lyrics, Tin Pan Alley, 1930 film censorship ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I should like to thank Professor Ivan Rabinowitz, my supervisor, who has been both my mentor and an unfailing source of encouragement; Dawie Malan who was so patient in sourcing material from libraries around the world with remarkable fortitude and good humour; Dr Robin Lee who suggested the title of my dissertation; Dr Elspa Hovgaard who provided academic and helpful comment; my husband, Henry Holloway, a musicologist of world renown, who had to share me with another man for three years; and the man himself, Cole Porter, whose lyrics have thrilled, and will continue to thrill, music lovers with their sophistication and wit. -

Here Are a Number of Recognizable Singers Who Are Noted As Prominent Contributors to the Songbook Genre

Music Take- Home Packet Inside About the Songbook Song Facts & Lyrics Music & Movement Additional Viewing YouTube playlist https://bit.ly/AllegraSongbookSongs This packet was created by Board-Certified Music Therapist, Allegra Hein (MT-BC) who consults with the Perfect Harmony program. About the Songbook The “Great American Songbook” is the canon of the most important and influential American popular songs and jazz standards from the early 20th century that have stood the test of time in their life and legacy. Often referred to as "American Standards", the songs published during the Golden Age of this genre include those popular and enduring tunes from the 1920s to the 1950s that were created for Broadway theatre, musical theatre, and Hollywood musical film. The times in which much of this music was written were tumultuous ones for a rapidly growing and changing America. The music of the Great American Songbook offered hope of better days during the Great Depression, built morale during two world wars, helped build social bridges within our culture, and whistled beside us during unprecedented economic growth. About the Songbook We defended our country, raised families, and built a nation while singing these songs. There are a number of recognizable singers who are noted as prominent contributors to the Songbook genre. Ella Fitzgerald, Fred Astaire, Rosemary Clooney, Nat King Cole, Sammy Davis Jr., Judy Garland, Billie Holiday, Lena Horne, Al Jolson, Dean Martin, Frank Sinatra, Mel Tormé, Margaret Whiting, and Andy Williams are widely recognized for their performances and recordings which defined the genre. This is by no means an exhaustive list; there are countless others who are widely recognized for their performances of music from the Great American Songbook. -

Cole Albert Porter (June 9, 1891 October 15, 1964) Was An

Cole Albert Porter (June 9, 1891 October 15, 1964) was an American composer and songwriter. Born to a wealthy family in Indiana, he defied the wishes of his dom ineering grandfather and took up music as a profession. Classically trained, he was drawn towards musical theatre. After a slow start, he began to achieve succe ss in the 1920s, and by the 1930s he was one of the major songwriters for the Br oadway musical stage. Unlike many successful Broadway composers, Porter wrote th e lyrics as well as the music for his songs. After a serious horseback riding accident in 1937, Porter was left disabled and in constant pain, but he continued to work. His shows of the early 1940s did not contain the lasting hits of his best work of the 1920s and 30s, but in 1948 he made a triumphant comeback with his most successful musical, Kiss Me, Kate. It w on the first Tony Award for Best Musical. Porter's other musicals include Fifty Million Frenchmen, DuBarry Was a Lady, Any thing Goes, Can-Can and Silk Stockings. His numerous hit songs include "Night an d Day","Begin the Beguine", "I Get a Kick Out of You", "Well, Did You Evah!", "I 've Got You Under My Skin", "My Heart Belongs to Daddy" and "You're the Top". He also composed scores for films from the 1930s to the 1950s, including Born to D ance (1936), which featured the song "You'd Be So Easy to Love", Rosalie (1937), which featured "In the Still of the Night"; High Society (1956), which included "True Love"; and Les Girls (1957). -

A Hep Kid with a Beat

A Hep Kid With a Beat The Early Years of Songwriter Jimmy McHugh By Richard Vacca If you are unfamiliar with Jimmy McHugh, the first thing to know is that he was a prolific Boston- born songwriter who prospered between the early 1920s and the mid 1950s. He had a way with a tune, and he composed some truly memorable contributions to the Great American Songbook. He was also an accomplished pianist, and made a living at it for a time, but that was always secondary to his song- writing. The second thing to know is that he was a born promoter. It didn’t matter what it was—a song, a show, a good cause, himself—he promoted it with gusto. He was a born salesman, blessed with a per- sonality brimming with energy, enthusiasm and charm. McHugh would have understood today’s mar- keting practices intuitively. He carefully tended the Jimmy McHugh brand. His highly compatible talents for music and promotion were formed in his home town of Boston, where he lived for the first 25 of his 74 years. James Francis McHugh was born on School Street in Jamaica Plain on July 10, 1893, the son of James, a plumber, and Julia, his music-loving mother. It was Julia who taught Jimmy how to play piano. His father wanted Jimmy to take up the trade, and he did try it for a short while, but he was destined for a career in music. His mother was his first teacher, and a fine one. Jimmy would noodle around on the piano while Julia listened, and the story he later told was that if she heard something imitative, a copy, she’d give him a rap across the knuckles. -

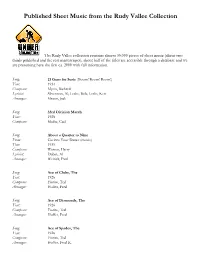

Published Sheet Music from the Rudy Vallee Collection

Published Sheet Music from the Rudy Vallee Collection The Rudy Vallee collection contains almost 30.000 pieces of sheet music (about two thirds published and the rest manuscripts); about half of the titles are accessible through a database and we are presenting here the first ca. 2000 with full information. Song: 21 Guns for Susie (Boom! Boom! Boom!) Year: 1934 Composer: Myers, Richard Lyricist: Silverman, Al; Leslie, Bob; Leslie, Ken Arranger: Mason, Jack Song: 33rd Division March Year: 1928 Composer: Mader, Carl Song: About a Quarter to Nine From: Go into Your Dance (movie) Year: 1935 Composer: Warren, Harry Lyricist: Dubin, Al Arranger: Weirick, Paul Song: Ace of Clubs, The Year: 1926 Composer: Fiorito, Ted Arranger: Huffer, Fred Song: Ace of Diamonds, The Year: 1926 Composer: Fiorito, Ted Arranger: Huffer, Fred Song: Ace of Spades, The Year: 1926 Composer: Fiorito, Ted Arranger: Huffer, Fred K. Song: Actions (speak louder than words) Year: 1931 Composer: Vallee, Rudy; Himber, Richard; Greenblatt, Ben Lyricist: Vallee, Rudy; Himber, Richard; Greenblatt, Ben Arranger: Prince, Graham Song: Adios Year: 1931 Composer: Madriguera, Enric Lyricist: Woods, Eddie; Madriguera, Enric(Spanish translation) Arranger: Raph, Teddy Song: Adorable From: Adorable (movie) Year: 1933 Composer: Whiting, Richard A. Lyricist: Marion, George, Jr. Arranger: Mason, Jack; Rochette, J. (vocal trio) Song: African Lament (Lamento Africano) Year: 1931 Composer: Lecuona, Ernesto Lyricist: Gilbert, L. Wolfe Arranger: Katzman, Louis Song: African Lament (Lamento Africano) -

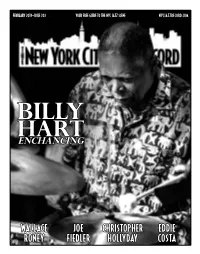

Wallace Roney Joe Fiedler Christopher

feBrUARY 2019—ISSUe 202 YOUr FREE GUide TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM BILLY HART ENCHANCING wallace joe christopher eddie roney fiedler hollyday costa Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East feBrUARY 2019—ISSUe 202 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 new york@niGht 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: interview : wallace roney 6 by anders griffen [email protected] Andrey Henkin: artist featUre : joe fiedler 7 by steven loewy [email protected] General Inquiries: on the cover : Billy hart 8 by jim motavalli [email protected] Advertising: encore : christopher hollyday 10 by robert bush [email protected] Calendar: lest we forGet : eddie costa 10 by mark keresman [email protected] VOXNews: LAbel spotliGht : astral spirits 11 by george grella [email protected] VOXNEWS by suzanne lorge US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or oBitUaries 12 by andrey henkin money order to the address above or email [email protected] FESTIVAL REPORT 13 Staff Writers Duck Baker, Stuart Broomer, Robert Bush, Kevin Canfield, CD reviews 14 Marco Cangiano, Thomas Conrad, Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Miscellany Tom Greenland, George Grella, 31 Anders Griffen, Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, event calendar Matthew Kassel, Mark Keresman, 32 Marilyn Lester, Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Jim Motavalli, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Scott Yanow Contributing Writers Brian Charette, Steven Loewy, As unpredictable as the flow of a jazz improvisation is the path that musicians ‘take’ (the verb Francesco Martinelli, Annie Murnighan, implies agency, which is sometimes not the case) during the course of a career. -

Lyricist's Lyrical Lyrics: Widening the Scope of Poetry Studies by Claiming the Obvious

Paper from the Conference “Current Issues in European Cultural Studies”, organised by the Advanced Cultural Studies Institute of Sweden (ACSIS) in Norrköping 15-17 June 2011. Conference Proceedings published by Linköping University Electronic Press: http://www.ep.liu.se/ecp_home/index.en.aspx?issue=062. © The Author. Lyricist’s Lyrical Lyrics: Widening the Scope 1 of Poetry Studies by Claiming the Obvious Geert Buelens Utrecht University/ Stellenbosch University [email protected] Poetry is all but absent from Cultural Studies. Most treatments of the genre tend to focus on canonized poets whose work is wilfully difficult and obscure. Alternative histories should be explored, opening up possibilities to view poetry again as a culturally relevant art form. The demotic and popular strain provides a case in point. From the Romantics onwards modern poetry linked itself with oral or folk traditions like the ballad. Socially the most popular of these forms is the pop lyric. Since the 1950s rock lyrics have been studied in Social Studies, Cultural Studies, Musicology and some English Departments, but rarely within the context of Poetics or Comparative Literature. Rap and canonized singer-songwriters like Dylan and Cohen are the exceptions to the rule. Systematic attention to both lyrics and performance may open up current ideas of what a poem is and how it works. 1 This article is the non copy-edited draft of a paper presented at the 2011 ACSIS conference ‘Current Issues in European Cultural Studies’, Norrköping, 15-17 June 2011 within the session ‘Revisiting the Literary Within Cultural Studies’. 495 LYRICIST’s LYRICAL LYRICS: WIDENING THE SKOPE OF POETRY STUDIES BY CLAIMING THE OBVIOUS Listen – I’m not dissin but there’s something that you’re missin Maybe you should touch reality KRS-One/Boogie Down Productions, ‘Poetry’ (1987) (in Bradley&DuBois 2010, 145) It is a truism of sorts to claim that Cultural Studies tries to understand the world we live in and to explain how cultural artefacts both reflect and construct that world and its inherent political tensions. -

CRLS Music Learning Expectations Grades 9-12 1St Year (A = All Students C = Choral Students P = Piano Students I = Instrumental Students)

CRLS Music Learning Expectations Grades 9-12 1st Year (A = all students C = choral students P = piano students I = instrumental students) CRLS Mass. Topic/Theme Key Understandings Assessments/Evidence Learning Standard Expectations 5.12-5.17 Historical/Cultural Students will: 6.5-6.8 Contexts of Music (A) Discuss 2 pieces of music (at least one of which was 7.5-7.10 heard live), detailing the title, composer, time and 8.6-8.11 place or origin, comparing and contrasting societal 9.5-9.9 function and relevance, societal support systems, 10.3-10.4 relevant technological advances, compositional form, instrumentation, and primary melodic/harmonic/rhythmic characteristics. In addition, students will make these comparisons to other musical works of the same period, works of another period and works from another discipline (dance/poetry) of the same period, interviewing at least one professional musician during the process. NOTE: all pieces shall be chosen from the following genres of music; • European classical • Jazz • Music representative of a specific ethnic or cultural group 1.10/3.11 Singing and Playing (A) Demonstrate good posture, diaphragmatic breathing, hand position and/or proper embouchure/facial & throat positioning as it applies to specific areas of study. 3.11 (I) Assemble and disassemble their instruments, and keep them in good basic repair. 3.11 (I) Coarse-tune their instruments mechanically using functions of the instruments themselves. CRLS Mass. Topic/Theme Key Understandings Assessments/Evidence Learning Standard Expectations