The Introduction of Pepsi and Mcdonald's Into The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SDN Changes 2014

OFFICE OF FOREIGN ASSETS CONTROL CHANGES TO THE Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons List SINCE JANUARY 1, 2014 This publication of Treasury's Office of Foreign AL TOKHI, Qari Saifullah (a.k.a. SAHAB, Qari; IN TUNISIA; a.k.a. ANSAR AL-SHARIA IN Assets Control ("OFAC") is designed as a a.k.a. SAIFULLAH, Qari), Quetta, Pakistan; DOB TUNISIA; a.k.a. ANSAR AL-SHARI'AH; a.k.a. reference tool providing actual notice of actions by 1964; alt. DOB 1963 to 1965; POB Daraz ANSAR AL-SHARI'AH IN TUNISIA; a.k.a. OFAC with respect to Specially Designated Jaldak, Qalat District, Zabul Province, "SUPPORTERS OF ISLAMIC LAW"), Tunisia Nationals and other entities whose property is Afghanistan; citizen Afghanistan (individual) [FTO] [SDGT]. blocked, to assist the public in complying with the [SDGT]. AL-RAYA ESTABLISHMENT FOR MEDIA various sanctions programs administered by SAHAB, Qari (a.k.a. AL TOKHI, Qari Saifullah; PRODUCTION (a.k.a. ANSAR AL-SHARIA; OFAC. The latest changes may appear here prior a.k.a. SAIFULLAH, Qari), Quetta, Pakistan; DOB a.k.a. ANSAR AL-SHARI'A BRIGADE; a.k.a. to their publication in the Federal Register, and it 1964; alt. DOB 1963 to 1965; POB Daraz ANSAR AL-SHARI'A IN BENGHAZI; a.k.a. is intended that users rely on changes indicated in Jaldak, Qalat District, Zabul Province, ANSAR AL-SHARIA IN LIBYA; a.k.a. ANSAR this document that post-date the most recent Afghanistan; citizen Afghanistan (individual) AL-SHARIAH; a.k.a. ANSAR AL-SHARIAH Federal Register publication with respect to a [SDGT]. -

Pepsi: Can a Soda Really Make the World a Better Place?

Short Case Pepsi: Can a Soda Really Make The World a Better Place? This year, PepsiCo did something that shocked the advertising world. After 23 straight years of running ads for its flagship brand on the Super Bowl, it announced that the number-two soft drink maker would be absent from the Big Game. But in the weeks leading up to Super Bowl XLIV, Pepsi was still the second-most discussed advertiser associated with the event. It wasn’t so much what Pepsi wasn’t doing that created such a stir as much as what it was doing. Rather than continuing with the same old messages of the past, focusing on the youthful nature of the Pepsi Generation, and using the same old mass-media channels, Pepsi is taking a major gamble by breaking new ground with its advertising program. Its latest campaign, called Pepsi Refresh, represents a major departure from its old promotion efforts in two ways: (1) The message centers on a theme of social responsibility, and (2) the message is being delivered with a fat dose of social media. At the center of the campaign is the Pepsi Refresh Project. PepsiCo has committed to award $20 million in grants ranging from $5,000 to $250,000 to organizations and individuals with ideas that will make the world a better place. The refresheverything.com Web site greets visitors with the headline, “What do you care about?” PepsiCo accepts up to 1,000 proposals each month in each of six different areas: health, arts and culture, food and shelter, the planet, neighborhoods, and education. -

Cultural Imperialism and Globalization in Pepsi Marketing

Cultural Imperialism and Globalization in Pepsi Marketing The increased speed and flow of information brought about by technology has influenced a massive global culture shift. Two consequences of this increased information exchange are cultural imperialism and globalization. Cultural imperialism is a heavily debated concept that “refers to how an ideology, a politics, or a way of life is exported into other territories through the export of cultural products” (Struken and Cartwright 397). The related concept of globalization “describes the progression of forces that have accelerated the interdependence of peoples to the point at which we can speak of a true world community” (Struken and Cartwright 405). A driving force of both cultural imperialism and globalization are major corporations, many of which are based in the United States. Brands like Pepsi are now known worldwide and not simply confined to one particular country or the western sphere. These global brands can be viewed “as homogenizing forces, selling the same tastes and styles throughout diverse cultures” (Stuken and Cartwright 402). Conversely, viewers in other countries are free to “appropriate what they see to make new meanings, meanings that may be not just different from but even oppositional to the ideologies” of these global advertising campaigns. By analyzing three recent aspects of Pepsi’s “Live for Now” global campaign, I will examine their relationship to cultural imperialism and globalization, as well as show how the use of an interactive website accounts for a multitude of factors to become the most effective aspect of the campaign. The Global Branding of Pepsi Advertising Pepsi cola was created in United States in the 1890s and originally sold as medicine (The Soda Museum). -

Soviet Ruble, Gold Ruble, Tchernovetz and Ruble-Merchandise Mimeograph

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt258032tg No online items Overview of the Soviet ruble, gold ruble, tchernovetz and ruble-merchandise mimeograph Processed by Hoover Institution Archives Staff. Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California 94305-6010 Phone: (650) 723-3563 Fax: (650) 725-3445 Email: [email protected] © 2009 Hoover Institution Archives. All rights reserved. Overview of the Soviet ruble, YY497 1 gold ruble, tchernovetz and ruble-merchandise mimeograph Overview of the Soviet ruble, gold ruble, tchernovetz and ruble-merchandise mimeograph Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California Processed by: Hoover Institution Archives Staff Date Completed: 2009 Encoded by: Machine-readable finding aid derived from MARC record by David Sun. © 2009 Hoover Institution Archives. All rights reserved. Collection Summary Title: Soviet ruble, gold ruble, tchernovetz and ruble-merchandise mimeograph Dates: 1923 Collection Number: YY497 Collection Size: 1 item (1 folder) (0.1 linear feet) Repository: Hoover Institution Archives Stanford, California 94305-6010 Abstract: Relates to the circulation of currency in the Soviet Union. Original article published in Agence économique et financière, 1923 July 18. Translated by S. Uget. Physical Location: Hoover Institution Archives Languages: English Access Collection is open for research. The Hoover Institution Archives only allows access to copies of audiovisual items. To listen to sound recordings or to view videos or films during your visit, please contact the Archives at least two working days before your arrival. We will then advise you of the accessibility of the material you wish to see or hear. Please note that not all audiovisual material is immediately accessible. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Archives. -

Russian America and the USSR: Striking Parallels by Andrei V

Russian America and the USSR: Striking Parallels by Andrei V. Grinëv Translated by Richard L. Bland Abstract. The article is devoted to a comparative analysis of the socioeconomic systems that have formed in the Russian colonies in Alaska and in the USSR. The author shows how these systems evolved and names the main reason for their similarity: the nature of the predominant type of property. In both systems, supreme state property dominated and in this way they can be designated as politaristic. Politariasm (from the Greek πολιτεία—the power of the majority, that is, in a broad sense, the state, the political system) is formation founded on the state’s supreme ownership of the basic means of production and the work force. Economic relations of politarism generated the corresponding social structure, administrative management, ideological culture, and even similar psychological features in Russian America and the USSR. Key words: Russian America, USSR, Alaska, Russian-American Company, politarism, comparative historical research. The selected theme might seem at first glance paradoxical. And in fact, what is common between the few Russian colonies in Alaska, which existed from the end of the 18th century to 1867, and the huge USSR of the 20th century? Nevertheless, analysis of this topic demonstrates the indisputable similarity between the development of such, it would seem, different-scaled and diachronic socioeconomic systems. It might seem surprising that many phenomena of the economic and social sphere of Russian America subsequently had clear analogies in Soviet society. One can hardly speak of simple coincidences and accidents of history. Therefore, the selected topic is of undoubted scholarly interest. -

APPLICATION of the CHARTER in UKRAINE 2Nd Monitoring Cycle A

Strasbourg, 15 January 2014 ECRML (2014) 3 EUROPEAN CHARTER FOR REGIONAL OR MINORITY LANGUAGES APPLICATION OF THE CHARTER IN UKRAINE 2nd monitoring cycle A. Report of the Committee of Experts on the Charter B. Recommendation of the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe on the application of the Charter by Ukraine The European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages provides for a control mechanism to evaluate how the Charter is applied in a State Party with a view to, where necessary, making recommendations for improving its language legislation, policy and practices. The central element of this procedure is the Committee of Experts, set up under Article 17 of the Charter. Its principal purpose is to report to the Committee of Ministers on its evaluation of compliance by a Party with its undertakings, to examine the real situation of regional or minority languages in the State and, where appropriate, to encourage the Party to gradually reach a higher level of commitment. To facilitate this task, the Committee of Ministers adopted, in accordance with Article 15, paragraph1, an outline for periodical reports that a Party is required to submit to the Secretary General. The report should be made public by the State. This outline requires the State to give an account of the concrete application of the Charter, the general policy for the languages protected under Part II and, in more precise terms, all measures that have been taken in application of the provisions chosen for each language protected under Part III of the Charter. The Committee of Experts’ first task is therefore to examine the information contained in the periodical report for all the relevant regional or minority languages on the territory of the State concerned. -

Underpinning of Soviet Industrial Paradigms

Science and Social Policy: Underpinning of Soviet Industrial Paradigms by Chokan Laumulin Supervised by Professor Peter Nolan Centre of Development Studies Department of Politics and International Studies Darwin College This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2019 Preface This dissertation is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It is not substantially the same as any that I have submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for a degree or diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. I further state that no substantial part of my dissertation has already been submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for any such degree, diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text It does not exceed the prescribed word limit for the relevant Degree Committee. 2 Chokan Laumulin, Darwin College, Centre of Development Studies A PhD thesis Science and Social Policy: Underpinning of Soviet Industrial Development Paradigms Supervised by Professor Peter Nolan. Abstract. Soviet policy-makers, in order to aid and abet industrialisation, seem to have chosen science as an agent for development. Soviet science, mainly through the Academy of Sciences of the USSR, was driving the Soviet industrial development and a key element of the preparation of human capital through social programmes and politechnisation of the society. -

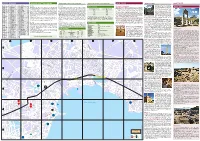

1 2 3 4 5 a B C D E

STREET REGISTER ARRIVING & GETTING AROUND ARRIVING & GETTING AROUND ARRIVING & GETTING AROUND WHAT TO SEE WHAT TO SEE WHAT TO SEE Amurskaya E/F-2 Krasniy Spusk G-3 Radishcheva E-5 By Bus By Plane Great Mitridat Stairs C-4, near the Lenina Admirala Vladimirskogo E/F-3 Khersonskaya E/F-3 Rybatskiy prichal D/C-4-B-5 Churches & Cathedrals pl. The stairs were built in the 1930’s with plans Ancient Cities Admirala Azarova E-4/5 Katernaya E-3 Ryabova F-4 Arriving by bus is the only way to get to Kerch all year round. The bus station There is a local airport in Kerch, which caters to some local Crimean flights Ferry schedule Avdeyeva E-5 Korsunskaya E-3 Repina D-4/5 Church of St. John the Baptist C-4, Dimitrova per. 2, tel. (+380) 6561 from the Italian architect Alexander Digby. To save Karantinnaya E-3 Samoylenko B-3/4 itself is a buzzing place thanks to the incredible number of mini-buses arriving during the summer season, but the only regular flight connection to Kerch is you the bother we have already counted them; Antonenko E-5 From Kerch (from Port Krym) To Kerch (from Port Kavkaz) 222 93. This church is a unique example of Byzantine architecture. It was built in Admirala Fadeyeva A/B-4 Kommunisticheskaya E-3-F-5 Sladkova C-5 and departing. Marshrutkas run from here to all of the popular destinations in through Simferopol State International, which has regular flights to and from Kyiv, there are 432 steps in all meandering from the Dep. -

Baltic States And

UNCLASSIFIED Asymmetric Operations Working Group Ambiguous Threats and External Influences in the Baltic States and Poland Phase 1: Understanding the Threat October 2014 UNCLASSIFIED UNCLASSIFIED Cover image credits (clockwise): Pro-Russian Militants Seize More Public Buildings in Eastern Ukraine (Donetsk). By Voice of America website (VOA) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:VOAPro- Russian_Militants_Seize_More_Public_Buildings_in_Eastern_Ukraine.jpg. Ceremony Signing the Laws on Admitting Crimea and Sevastopol to the Russian Federation. The website of the President of the Russian Federation (www.kremlin.ru) [CC-BY-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ceremony_signing_ the_laws_on_admitting_Crimea_and_Sevastopol_to_the_Russian_Federation_1.jpg. Sloviansk—Self-Defense Forces Climb into Armored Personnel Carrier. By Graham William Phillips [CCBY-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons, http://commons.wikimedia. org/wiki/File:BMDs_of_Sloviansk_self-defense.jpg. Dynamivska str Barricades on Fire, Euromaidan Protests. By Mstyslav Chernov (http://www.unframe.com/ mstyslav- chernov/) (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dynamivska_str_barricades_on_fire._ Euromaidan_Protests._Events_of_Jan_19,_2014-9.jpg. Antiwar Protests in Russia. By Nessa Gnatoush [CC-BY-2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Euromaidan_Kyiv_1-12-13_by_ Gnatoush_005.jpg. Military Base at Perevalne during the 2014 Crimean Crisis. By Anton Holoborodko (http://www. ex.ua/76677715) [CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:2014-03-09_-_Perevalne_military_base_-_0180.JPG. -

Crimea______9 3.1

CONTENTS Page Page 1. Introduction _____________________________________ 4 6. Transport complex ______________________________ 35 1.1. Brief description of the region ______________________ 4 1.2. Geographical location ____________________________ 5 7. Communications ________________________________ 38 1.3. Historical background ____________________________ 6 1.4. Natural resource potential _________________________ 7 8. Industry _______________________________________ 41 2. Strategic priorities of development __________________ 8 9. Energy sector ___________________________________ 44 3. Economic review 10. Construction sector _____________________________ 46 of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea ________________ 9 3.1. The main indicators of socio-economic development ____ 9 11. Education and science ___________________________ 48 3.2. Budget _______________________________________ 18 3.3. International cooperation _________________________ 20 12. Culture and cultural heritage protection ___________ 50 3.4. Investment activity _____________________________ 21 3.5. Monetary market _______________________________ 22 13. Public health care ______________________________ 52 3.6. Innovation development __________________________ 23 14. Regions of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea _____ 54 4. Health-resort and tourism complex_________________ 24 5. Agro-industrial complex __________________________ 29 5.1. Agriculture ____________________________________ 29 5.2. Food industry __________________________________ 31 5.3. Land resources _________________________________ -

Russian Ruble, Rub

As of March 16th 2015 RUSSIA - RUSSIAN RUBLE, RUB Country: Russia Currency: Russian Ruble (RUB) Phonetic Spelling: {ru:bil} Country Overview Abbreviation: RUB FOREIGN EXCHANGE Controlled by the Central Bank of Russia (http://www.cbr.ru/eng/) The RUB continues Etymology to be affected by the oil price shock, escalating capital outflows, and damaging The origin of the word “rouble” is derived from the economic sanctions. The Russian ruble (RUB) continued to extend its losses and Russian verb руби́ть (rubit’), which means “to chop, cut, suffered its largest one-day decline on Dec 1st against the US dollar (USD) — less than to hack.” Historically, “ruble” was a piece of a certain a month after allowing the RUB to float freely. The RUB’s slide reflects the fact that weight chopped off a silver oblong block, hence the Russia is among the most exposed to falling oil prices and is particularly vulnerable to name. Another version of the word’s origin comes from the Russian noun рубец, rubets, which translates OPEC’s recent decision to maintain its supply target of 30-million-barrels per day. This to the seam that is left around the coin after casting, combined with the adverse impact of Western sanctions has contributed to the RUB’s therefore, the word ruble means “a cast with a seam” nearly 40% depreciation vis-à-vis the USD since the start of 2014. In this context, the Russian Central Bank will likely hike interest rates at its next meeting on December In English, both the spellings “ruble” and “rouble” are 11th. -

Consumerism, Art, and Identity in American Culture

ABSTRACT OKAY, MAYBE YOU ARE YOUR KHAKIS: CONSUMERISM, ART, AND IDENTITY IN AMERICAN CULTURE by Meghan Triplett Bickerstaff This thesis explores the evolving relationship between the cultural realms of art and the marketplace. The practice of “coolhunting,” or finding original fashions and ideas to co-opt and market to a mainstream audience, is increasingly being used in corporate America. The Toyota Scion and its advertising campaign are examples of such commodification, and they are considered within the context of Roland Marchand and Thomas Frank’s histories and theories of advertising. The novels Pattern Recognition by William Gibson and The Savage Girl by Alex Shakar both feature main characters who are coolhunters, and both approach the problem of the imposition of capital into the realm of art but formulate responses to the problem very differently. This literature offers insight into the important relationship between consumption and identity in American culture in the early twenty-first century. Okay, Maybe You Are Your Khakis: Consumerism, Art, and Identity in American Culture A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of the Arts Department of English by Meghan Triplett Bickerstaff Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2004 _________________________ Advisor: C. Barry Chabot _________________________ Reader: Timothy D. Melley _________________________ Reader: Whitney A. Womack Table of Contents Chapter 1: They’re Selling Us Aspirin for Our Broken Hearts 1 Chapter 2: Time, Space, and Critical Distance in Pattern Recognition 13 Chapter 3: The Savage Girl as an Oppositional Text 22 Chapter 4: Attention Shoppers: Authenticity is Dead, But Please Don’t 37 Stop Looking for It Works Cited 47 ii Acknowledgements I am lucky to have had a warm and positive environment in which to work, and I would like to extend my gratitude toward several people who made this possible.