Is Northeast Poised for Lasting Peace ?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2021081046.Pdf

Samuxchana Vc Biock Kutcha house beneficiary list under Kakraban PD Answe Father Category APSWANI DEBBARMA TR1153198 SUBHASH DEBBARMA Kutcha Wall Yes RATAN KUMAR MURASING TR1128768 MANGALPAD MURASING Kutcha Wall Yes TR1128773 AMAR DEBBARMA ANANDA DEBBARMA Kutcha Wall Yes GUU PRASAD DEBBARMA Yes TR1177025 |MANYA LAL DEBBARMA Kutcha Wall TR1177028 HALEM MIA MNOHAR ALI Kutcha Wal Yes GURU PRASAD DEBBARMA Kutcha Nall TR1212148 SUNIL DEBBARMA Yes SURENDRA DEBBARMA Yes TR1128767 CHANDRA MANI DEBBARMA Kutcha Wall TR1235047 SADHANI DEBBARMA RABI TRIPURA Kutcha Wall Yes Kutcha Wall Yes TR1212144 JOY MOHAN DEBBARMA ARANYA PADA DEBBARMA RUHINI KUMAR DEB8ARMA Kutcha Wall Yes 10 TR1279857 HARIPADA DEBBARMA 11 TRL279860 SURJAYA MANIK DEBBARMA SURESH DEBBARMA Kutcha Wall Yes SHANTA KUMAR TRIPURA Kutcha Wall Yes 12 TR1200564 KRISHNAMANI TRIPURA 1258729 BIRAN MANI TRIPURA MALINDRA TRIPURA Kutcha Wall Yes Kutcha Wall 14 TR1165123 SURESH DEBBARMA BISHNU HARI DEBBARMA Yes 128769 PURNA MOHAN DEBBARMA SURENDRA DEBBARMA Kutcha Wall 1246344 GOURANGA DEBBARMA GURU PRASAD DEBBARMA Kutcha Wali Yes 17 RL140 83 KANTI BALA NOATIA SAHADEB DEBBARMA Kutcha Wa!l Yes 18 290885 BINAY DEBBARMA HACHUBROY DEBBARMA Kutcha Wali Yes 77024 SUKHCHANDRA MURASING MANMOHAN MURASING Kutcha Wall es 20 T1188838 SUMANGAL DEBBARMA JAINTHA KUMAR DEBBARMA Kutcha Wall Yes 2 T290883 PURRNARAY NOYATIYA DURRBA CHANDRA NOYATIYA Kutcha Wall Yes 212143 SHUKURAN!MURASING KRISHNA KUMAR MURASING Kutcha Wall Yes 279859 BAISHAKH LAKKHI MURASINGH PATHRAI MURASINGH Kutcha Wall Yes 128771 PULIN DEBBARMA -

A Translation of Kokborok Poetry in English by Ashes Gupta

Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities, Vol. IX, No. 1, 2017 0975-2935 DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.21659/rupkatha.v9n1.36 Full Text: http://rupkatha.com/V9/n1/v9n136.pdf Review Article The Fragrant Joom revisited: A translation of Kokborok poetry in English by Ashes Gupta Ashes Gupta, The Fragrant Joom revisited: A translation of Kokborok poetry in English (Akshar Publications, Agartala 2017), 144 pages, Rs. 250. Reviewed by Sukla Singha Research Scholar, Department of English, Tripura University, Tripura, India. Orcid: 0000-0003-4948-7297. Email: [email protected] When one wishes to read and understand a piece of literary writing (poem or prose) originally written in a language very different from one’s own and probably even beyond one’s comprehension, one is left with no other choice but to depend on the translation of the original text, in a language that one is familiar with, although not necessarily one’s mother tongue. The text in question is The Fragrant Joom revisited, a collection of poems originally written in Kokborok, the principal language of the natives of the state of Tripura, and translated to English by Ashes Gupta, eminent translator and academician of the state. The first edition of the book had come out in 2006, and in the words of the translator and editor: “A decade has passed since the first publication of The Fragrant Joom in 2006. It’s time to revisit the old joom again, time to feel new blooms and new fragrances that time had brought to life in a land criss-crossed by myriad influences - social, economic, cultural and political.” In the foreword to the second edition, Gupta bares all his heart and words describing why he started taking a keen interest in Kokborok poetry despite belonging to a different community (Bengali) of the state. -

Language Wing

LANGUAGE WING UNDER EDUCATION DEPARTMENT TRIPURA TRIBAL AREAS AUTONOMOUS DISTRICT COUNCIL KHUMULWNG, TRIPURA -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- PROMOTION OF KOKBOROK AND OTHER TRIBAL LANGUAGES IN TTAADC The Language Wing under Education Department in TTAADC was started in 1994 by placing a Linguistic Officer. A humble start for development of Kokborok had taken place from that particular day. Later, activities has been extended to other tribal languages. All the activities of the Language Wing are decided by the KOKBOROK LANGUAGE DEVELOPMENT COMMITTEE (KLDC) chaired by the Hon’ble Executive Member for Education Department in TTAADC. There are 12(twelve) members in the Committee excluding Chairman and Member- Secretary. The members of the Committee are noted Kokborok Writers, Poets, Novelist and Social Workers. The present members of the KLDC ar:; Sl. No. Name of the Members and full address 01. Mg. Radha Charan Debbarma, Chairman Hon’ble Executive Member, Education, TTAADC 02. Mg. Rabindra Kishore Debbarma, Member Pragati Bidya Bhavan, Agartala 03. Mg. Shyamlal Debbarma, Member MDC, TTAADC, Khumulwng 04. Mg. Bodhrai Debbarma, Member MGM HS School, Agartala 05. Mg. Chandra Kanta Murasingh, Member Ujan Abhoynagar, Agartala 06. Mg. Upendra Rupini, Member Brigudas Kami, Champaknagar, West Tripura 07. Mg. Laxmidhan Murasing, Member MGM HS School, Agartala 08. Mg. Narendra Debbarma, Member SCERT, Agartala 09. Mg. Chitta Ranjan Jamatia, Member Ex. HM, Killa, Udaipur, South Tripura 10. Mg. Gitya Kumar Reang, Member Kailashashar, North Tripura 11. Mg. Rebati Tripura, Member MGM HS School, Agartala 12. Mg. Ajit Debbarma, Member ICAT Department, Agartala 13. Mg. Sachin Koloi, Member Kendraicharra SB School, Takarjala 14. Mr. Binoy Debbarma, Member-Secretary Senior Linguistic Officer, Education Department There is another committee separately constituted for the development of Chakma Language namely CHAKMA LANGUAGE DEVELOPMENT COMMITTEE with the following members: Sl No Name of the members and full address 01. -

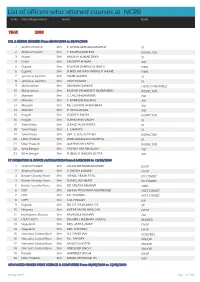

List of Officers Who Attended Courses at NCRB

List of officers who attened courses at NCRB Sr.No State/Organisation Name Rank YEAR 2000 SQL & RDBMS (INGRES) From 03/04/2000 to 20/04/2000 1 Andhra Pradesh Shri P. GOPALAKRISHNAMURTHY SI 2 Andhra Pradesh Shri P. MURALI KRISHNA INSPECTOR 3 Assam Shri AMULYA KUMAR DEKA SI 4 Delhi Shri SANDEEP KUMAR ASI 5 Gujarat Shri KALPESH DHIRAJLAL BHATT PWSI 6 Gujarat Shri SHRIDHAR NATVARRAO THAKARE PWSI 7 Jammu & Kashmir Shri TAHIR AHMED SI 8 Jammu & Kashmir Shri VIJAY KUMAR SI 9 Maharashtra Shri ABHIMAN SARKAR HEAD CONSTABLE 10 Maharashtra Shri MODAK YASHWANT MOHANIRAJ INSPECTOR 11 Mizoram Shri C. LALCHHUANKIMA ASI 12 Mizoram Shri F. RAMNGHAKLIANA ASI 13 Mizoram Shri MS. LALNUNTHARI HMAR ASI 14 Mizoram Shri R. ROTLUANGA ASI 15 Punjab Shri GURDEV SINGH INSPECTOR 16 Punjab Shri SUKHCHAIN SINGH SI 17 Tamil Nadu Shri JERALD ALEXANDER SI 18 Tamil Nadu Shri S. CHARLES SI 19 Tamil Nadu Shri SMT. C. KALAVATHEY INSPECTOR 20 Uttar Pradesh Shri INDU BHUSHAN NAUTIYAL SI 21 Uttar Pradesh Shri OM PRAKASH ARYA INSPECTOR 22 West Bengal Shri PARTHA PRATIM GUHA ASI 23 West Bengal Shri PURNA CHANDRA DUTTA ASI PC OPERATION & OFFICE AUTOMATION From 01/05/2000 to 12/05/2000 1 Andhra Pradesh Shri LALSAHEB BANDANAPUDI DY.SP 2 Andhra Pradesh Shri V. RUDRA KUMAR DY.SP 3 Border Security Force Shri ASHOK ARJUN PATIL DY.COMDT. 4 Border Security Force Shri DANIEL ADHIKARI DY.COMDT. 5 Border Security Force Shri DR. VINAYA BHARATI CMO 6 CISF Shri JISHNU PRASANNA MUKHERJEE ASST.COMDT. 7 CISF Shri K.K. SHARMA ASST.COMDT. -

Tripura HDR-Prelimes

32 TRIPURA HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORT Tripura Human Development Report 2007 Government of Tripura PUBLISHED BY Government of Tripura All rights reserved PHOTO CREDITS V.K. Ramachandran: pages 1, 2 (all except the middle photo), 31, 32, 34, 41, 67 (bottom photo), 68 (left photo), 69, 112 (bottom photo), 124 (bottom photo), 128. Government of Tripura: pages 2 (middle photo), 67 (top photo), 68 (right photo), 72, 76, 77, 79, 89, 97, 112 (top photo), 124 (top left and top right photos). COVER DESIGN Alpana Khare DESIGN AND PRINT PRODUCTION Tulika Print Communication Services, New Delhi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This Report is the outcome of active collaboration among Departments of the Government of Tripura, independent academics and researchers, and staff and scholars of the Foundation for Agrarian Studies. The nodal agency on the official side was the Department of Planning and Coordination of the Government of Tripura, and successive Directors of the Department – A. Guha, S.K. Choudhury, R. Sarwal and Jagdish Singh – have played a pivotal role in coordinating the work of this Report. S.K. Panda, Principal Secre- tary, took an active personal interest in the preparation of the Report. The Staff of the Department, and M. Debbarma in particular, have worked hard to collect data, organize workshops and help in the preparation of the Re- port. The process of planning, researching and writing this Report has taken over two years, and I have accumulated many debts on the way. The entire process was guided by the Steering Committee under the Chairmanship of the Chief Secretary. The members of the Steering Committee inclu-ded a representative each from the Planning Commission and UNDP, New Delhi; the Vice-Chancellor, Tripura University; Professor Abhijit Sen, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi and Professor V. -

Classifiers in Kokborok

International Journal of Linguistics and Literature (IJLL) ISSN(P): 2319-3956; ISSN(E): 2319-3964 Vol. 4, Issue 5, Aug - Sep 2015, 33-42 © IASET CLASSIFIERS IN KOKBOROK S. GANESH BASKARAN Associate Professor, Department of Linguistics, Rabindranath Tagore School of Indian Languages and Cultural Studies, Assam University, Silchar, Dorgakona, Silchar, Assam, India ABSTRACT Classifiers are defined as morphemes which occur ‘in surface structures under specific conditions’; denote ‘some salient perceived or imputed characteristics of the entity to which an associated noun refers’ (Allan 1977: 285). The classifiers are primarily divided into sortal and mensural subtypes. Sortal classifiers typically individuate referents in terms of the kind of entity it is, particularly with respect to inherent properties such as shape and animacy while the mensural one distinguishes the referents in terms of quantum or amount (Lyons 1977: 463). Thepresent paper is a humble attempt to describe morphosemantic aspects of Kokborok classifiers in the light of synchronic approaches. The study is confined to the West Tripura district of Tripura State. KEYWORDS: Kokborok, Classifier, Numeral Classifiers, Sortal and Mensural Classifiers INTRODUCTION The word ‘kokborok’ is a compound word. ‘ kok ’ means ‘ language ’ and ‘ borok ’ means ‘ people ’. According to 2001 Census of India, the total population of Kokborok speakers in the State of Tripura was 761964. Robert Shafer (1966-74) has made totally different classification of Sino-Tibetan languages than from other authors. He divides Tibeto- Burman into four main groups: Bodic, Baric, Burmic and Karenic. According to Shafer, Kokborok belongs to the Western Units of the Barish Section within the Baric Subdivision of Sino-Tibetan. -

Kokborok 4Th Semester Unit-I MCQ Quetion Peper 1. Hachuk K

Swami Vivekananda Mahavidyala Department of Kokborok Question Bank:- Kokborok 4th semester Unit-i MCQ Quetion peper 1. Hachuk khuri o kothomayung swinai sabo? A) Sudhanwa Debbarma. B) shyamlal Debbarma C) Sunil Debbarma D) Budharai Debbarma 2. Hachuk khuri o kothomayung bo bisi o karijak? A) 1987 bisio B) 1978 bisio C) 1989 bisio D) 1998 bisio 3. Narenni buphani mung tamo? A) Wakhirai B) Budhiram C) Budharai D) Tokhirai 4. Narenni bahanokni mung tamo? A) Mita B) Sobita C) Madhabi D) Molina 5. Padmaboti Sabo? A) Narenni buma B) Sobitani buma C) Madhabini buma D) Mitani buma 6. Narenni bibini mung tamo? A) Kwchakti B) Kuphuti C) Kormoti D) Komola 7. Gupen thakurni bihikni mung tamo? A) Chandramolika B) Bonomala C) Padmabati D) Sukhulakhi 8. Gupen thakurni bwsajwkni mung tamo? A) Sabita B) Malina C) Mita D) Komola 9. Mitani buphayungni mung tamo? A) Molen B) Milon C) Alen D) Naren 10. Bharat chandrani bihikni mung wngkh---------- A) Bonomala B) Komola C) Mita D) Kormoti 11. Boktamoni saboni buchu? A) Mitani B) Molinani C) Sabitani D) Madhabini 12. Mongal sardar wngkha------------------------- A) Padmabati bwsai B) Sukhulakhini bwsai C) Biswalakhini bwsai D) Sabitani bupha 13. Mongal sardarni bwsajwkni mung tamo? A) Madhabi B) Sabita C) Molina D) Mita 14. Gonga charanni bwswlani mung tamo? A) Milon B) Bharat C) Pramud ranjan D) Bimol 15. Naren songni kamini mung tamo? A) Mwtai dongor kami B) Kuthumrai kami C) Mwtai twisa kami D) Athukrai kami 16. Mwtai dongor kami Aguli bwswk chal? A) Khelpesa B) Kholpedok C) Kholpeba D) Kholpechi 17. Horjoi wngkha-------------------------------- A) Budhuraini wai B) Mongal sordarni wai C) Bharatni wai D) Gupenni wai 18. -

20 Clothing Preference of the 21St Century Tribal Women: a Study of the Transformation in the Costume of Tribal Women of Tripura, India

20 Clothing preference of the 21st Century tribal women: a study of the transformation in the costume of tribal women of Tripura, India. Authors: Paramita Sarkar, Nilanjana Bairagi National Institute of Fashion Technology, India Corresponding author [email protected] Keywords Ethnographic, regional costume, traditional costume transformation, Tripuri tribe, Reang tribe, Abstract An ethnographic research was conducted from 2011 to 2016, to study the tribal costume of the Tripuri and Reang tribe. Tripura is situated in the northeastern part of India. It is surrounded on the north, west, and south by Bangladesh and is accessible to the rest of India through Assam and Mizoram state. Tripura witnessed the emergence of a new culture, with the flow of immigrants in the state during the post- independence period. There are about nineteen different tribes living in Tripura. The Tripuri and Reang are the most primitive tribes of Tripura. The uniqueness of the tribal community is expressed in the hand-woven textiles. The tribal communities are known for their conformity in dressing, a form of social interaction within the tribal community in which one tries to maintain standards set by the group. With modernisation and socio-economic development, the preferences of the modern tribal women have changed from the traditional way of dressing and adorning. The traditional costume has also undergone changes in terms of textiles, colour, and motifs as well as in draping style. The research paper focuses on the transformation that has taken place in the traditional costume, while the Tripuri and Reang tribal women also strive to preserve their cultural identity. -

Kokborok (General) (Choice Based Credit System) (Effective from the Academic Session 2018-2019)

SYLLABUS & PROGRAMME STRUCTURE Kokborok (General) (Choice Based Credit System) (Effective from the Academic Session 2018-2019) Fifth Semester MAHARAJA BIR BIKRAM UNIVERSITY AGARTALA, TRIPURA: 799004 Semester Core Course Ability Skill Discipline Generic Enhancement Enhancement Specific Elective (12) Compulsory Course Course (SEC) Elective (GE) Kokborok (General) | Semester - V (AECC) (2) (2) (DSE) (2) (4) 1 Compulsory English-1 AECC1 DSC- 1 A : Environmental (Paper-I of choice of Science subject-I) DSC- 2 A (Paper-I of choice of subject-II) 2 Compulsory English-2 AECC2 DSC- 1 B : (Paper-II of choice of (English/MIL) subject-I) (English/Bengali/Ko DSC- 2 B kborak/Hindi) (Paper-II of choice of (Communication) subject-II) 3 Compulsory MIL-1 SEC1 (Alternative (From Choice English/Bengali/Kokborak/Hi of subject-I) ndi) DSC- 1 C (Paper-III of choice of subject-I) DSC- 2 C (Paper-III of choice of subject-II) 4 Compulsory MIL-2 SEC2 (From (Alternative Choice of English/Bengali/Kokborak/Hi subject-II) ndi) DSC- 1D (Paper-IV of choice of subject-I) DSC- 2D (Paper-IV of choice of subject-II) 5 SEC3 (From DSE1A GE-1 (Choice of (From Choice (From subject-I) of subject-I) Choice of DSE2A (From subject-I) Choice of subject-II) 6 SEC4 (From DSE1B (From GE-2 (Choice of Choice of (From subject-II) subject-I) Choice of DSE2B subject-II) (From Choice of subject-II) PROGRAMME STRUCTURE Structure of Proposed CBCS Syllabus for B.A/B.Com (General) Kokborok (General) | Semester - V Semester – V DSE – Paper – I (A) ( General ) TOTALMARKS – 100 (End Semester-80; Internal-20) Unit-I Short stories 1. -

India and Bangladesh: Internal Challenges and External Relations

IPCS ISSUE BRIEF NO 137 FEBRUARY 2010 India and Bangladesh Internal Challenges and External Relations Smruti S Pattanaik Research Fellow, IDSA On January 6, the Awami League government killing. The government set up two commissions to celebrated one year in office. While addressing enquire into the matter. However, one of the to the nation, Sheikh Hasina said “We want to reports that were made public has not revealed free the country of corruption, misrule, illiteracy any conspiracy angle where outsiders may have and poverty by 2021”. It’s a long way to go, but been involved. The report attributed the mutiny to one year is too short a time to judge the long existing grievances of the BDR. The incident is government and make an assessment of its attributed to intelligence failure. performance. Currently the BDR trials are being held to try the The government has taken a firm decision to mutineers who were involved in this carnage. The establish war crime tribunals for the trial of war name of the BDR is changed to Bangladesh Border criminals despite pressures from various quarters. Guards but it continues to be seconded by officers The manner in which it handled the mutiny in the from the Army. It needs to be mentioned that one Bangladesh Rifles and its decision to expose the of the demands of the mutineers was to promote involvement of two senior officers from the officers from within the BDR to such posts. The National Security Intelligence who were involved Government has agreed to disband four battalions in the Chittagong arms haul indicate that the which were directly involved in the mutiny. -

TSR Female Candidates.Pdf

ROAD MAP OF TRIPURA Q 16 Km Airport to TSR 2nd Bn 15 Km Railway station to t TSR 2nd Bn 7 Km Bus Station to TSR v 2nd Bn Schedule for PST & PET (Outdoor Test) of female candidates for the post of Riflemen (GD) and Riflemen (Tradesmen) towards raising of 02 (two) new India Reserve (IR) Battalions for the State of Tripura S/No Registration Name of C/O Female Categor DOB Education Village PO PS Dist State Pin No Post Inside / Others Date of No applicant y applied for Outside outdoor test 1 5 Jayashree Das Sadip Das Female SC 25/02/1998 12th Bhattapuku A.D.Nagar A.D.Nagar West Tripura 799003 Riflemen(G Inside 26-07-2021 Passed r Kalitilla D) 2 7 Rajib Rani Kushilian Female ST 10/09/1999 12th Monithang Thelakung Jampuijala Sepahijala Tripura 799102 Riflemen(S Inside 26-07-2021 Kaipeng Kaipeng Passed weeper) 3 11 Susmita Saha Debasish Saha Female UR 31/12/1997 Graduate Town Agartala East West Tripura 799001 Riflemen(G Inside 26-07-2021 Pratapgarh Agartala D) 4 12 Rupali Khatun Jahagir Miah Female UR 13/10/1998 12th Rajnagar Agartala West West Tripura 799001 Riflemen(G Inside 26-07-2021 Passed Agartala D) 5 13 Jhuma Sarkar Harimal Sarkar Female SC 13/07/1999 12th Sanmura Lankamura West West Tripura 799009 Riflemen(G Inside 26-07-2021 Passed Agartala D) 6 17 Ranjana Singha Madan Mohan Female OBC 04/02/1997 12th Betcherra Kumarghat Kumarghat Unakoti Tripura 799266 Riflemen(G Inside 26-07-2021 Singha Passed D) 7 24 Punam Sarkar Ratan Sarkar Female SC 25/12/1995 12th Sidhai Sidhai Sidhai West Tripura 799212 Riflemen(G Inside 26-07-2021 Passed Mohanpur D) 8 27 Sunita Debbarma Uttam Debbarma Female ST 10/09/1998 9th Passed Chikanchar Laticherra Bishramganj Sepahijala Tripura 799103 Riflemen(G Inside 26-07-2021 a D) 9 40 Achri Debbarma Lt. -

The State Strikes Back: India and the Naga Insurgency

Policy Studies 52 The State Strikes Back: India and the Naga Insurgency Charles Chasie and Sanjoy Hazarika About the East-West Center The East-West Center is an education and research organization estab- lished by the U.S. Congress in 1960 to strengthen relations and under- standing among the peoples and nations of Asia, the Pacific, and the United States. The Center contributes to a peaceful, prosperous, and just Asia Pacific community by serving as a vigorous hub for cooperative research, education, and dialogue on critical issues of common concern to the Asia Pacific region and the United States. Funding for the Center comes from the U.S. government, with additional support provided by private agencies, individuals, foundations, corporations, and the gov- ernments of the region. About the East-West Center in Washington The East-West Center in Washington enhances U.S. engagement and dia- logue with the Asia-Pacific region through access to the programs and expertise of the Center and policy relevant research, publications, and out- reach activities, including those of the U.S. Asia Pacific Council. The State Strikes Back: India and the Naga Insurgency Policy Studies 52 ___________ The State Strikes Back: India and the Naga Insurgency ___________________________ Charles Chasie and Sanjoy Hazarika Copyright © 2009 by the East-West Center The State Strikes Back: India and the Naga Insurgency by Charles Chasie and Sanjoy Hazarika ISBN: 978-1-932728-79-8 (online version) ISSN: 1547-1330 (online version) East-West Center in Washington 1819 L Street, NW, Suite 200 Washington, D.C. 20036 Tel: 202-293-3995 Fax: 202-293-1402 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.eastwestcenter.org/washington Online at: www.eastwestcenter.org/policystudies This publication is a product of the project on Internal Conflicts and State-Building Challenges in Asia.