Tripura HDR-Prelimes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 43 Electoral Statistics

CHAPTER 43 ELECTORAL STATISTICS 43.1 India is a constitutional democracy with a parliamentary system of government, and at the heart of the system is a commitment to hold regular, free and fair elections. These elections determine the composition of the Government, the membership of the two houses of parliament, the state and union territory legislative assemblies, and the Presidency and vice-presidency. Elections are conducted according to the constitutional provisions, supplemented by laws made by Parliament. The major laws are Representation of the People Act, 1950, which mainly deals with the preparation and revision of electoral rolls, the Representation of the People Act, 1951 which deals, in detail, with all aspects of conduct of elections and post election disputes. 43.2 The Election Commission of India is an autonomous, quasi-judiciary constitutional body of India. Its mission is to conduct free and fair elections in India. It was established on 25 January, 1950 under Article 324 of the Constitution of India. Since establishment of Election Commission of India, free and fair elections have been held at regular intervals as per the principles enshrined in the Constitution, Electoral Laws and System. The Constitution of India has vested in the Election Commission of India the superintendence, direction and control of the entire process for conduct of elections to Parliament and Legislature of every State and to the offices of President and Vice- President of India. The Election Commission is headed by the Chief Election Commissioner and other Election Commissioners. There was just one Chief Election Commissioner till October, 1989. In 1989, two Election Commissioners were appointed, but were removed again in January 1990. -

Social Media Stars:Kerala

SOCIAL MEDIA STARS: KERALA Two people whose reach goes beyond Kerala and its politics — Congress MP Shashi Tharoor and BJP’s surprise candidate for the Thiruvananthapuram Assembly constituency former cricketer S Sreesanth — lead the Twitter charts in the state. Chief Minister Oommen Chandy and BJP state president K Rajasekaran are also active, often tweeting in Malayalam. Due to long-standing alliances in the state, the United Democratic Front (UDF) led by the Congress has a handle of its own, in addition to independent handles of the parties. Neither the Left Front nor its leaders seem to have figured out Twitter. In the last of a four-part series on social media stars in the poll-bound states of Tamil Nadu, West Bengal, Assam and Kerala, N Sundaresha Subramanian looks at the Twitter scene in God’s Own Country OOMMEN CHANDY Chief Minister, Kerala (Congress) Twitter Handle: @Oommen_Chandy Tweets No. of followers 6,129 51.4K SHASHI THAROOR Congress MP, Thiruvananthapuram Twitter Handle: @ShashiTharoor S SREESANTH Tweets No. of followers BJP candidate, Thiruvananthapuram 30.8K 4.09M Twitter Handle: @sreesanth36 Tweets No. of followers 6,268 1.04M PARTY HANDLES UDF KERALA V MURALEEDHARAN Twitter Handle: @udfkerala BJP veteran Tweets No. of followers Twitter Handle: @MuraliBJP 103 4,602 Tweets No. of followers 625 4,415 CPI(M) KERALAM Twitter Handle: @CPIM_Keralam KUMMANAM RAJASEKHARAN Tweets No. of followers 4,127 State president, BJP 958 Twitter Handle: @Kummanam Tweets No. of followers BJP KERALAM 1,324 10.8K Twitter Handle: @BJP4Keralam Tweets No. of followers RAMESH 3,993 4,906 CHENNITHALA Home Minister , Kerala (Congress) Twitter Handle: @chennithala KERALA CONGRESS Tweets No. -

West Tripura District, Tripura

कᴂद्रीय भूमि जल बो셍ड जल संसाधन, नदी विकास और गंगा संरक्षण विभाग, जल शक्ति मंत्रालय भारत सरकार Central Ground Water Board Department of Water Resources, River Development and Ganga Rejuvenation, Ministry of Jal Shakti Government of India AQUIFER MAPPING AND MANAGEMENT OF GROUND WATER RESOURCES WEST TRIPURA DISTRICT, TRIPURA उत्तर पूिी क्षेत्र, गुिाहाटी North Eastern Region, Guwahati GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF JAL SHAKTI DEPARTMENT OF WATER RESOURCES, RIVER DEVELOPMENT & GANGA REJUVENATION CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD REPORT ON “AQUIFER MAPPING AND MANAGEMENT PLAN OF WEST TRIPURA DISTRICT, TRIPURA” (AAP 2017-18) By Shri Himangshu Kachari Assistant Hydrogeologist Under the supervision of Shri T Chakraborty Officer In Charge, SUO, Shillong & Nodal Officer of NAQUIM, NER CONTENTS Page no. 1. Introduction 1-20 1.1 Objectives 1 1.2 Scope of the study 1 1.2.1 Data compilation & data gap analysis 1 1.2.2 Data Generation 2 1.2.3 Aquifer map preparation 2 1.2.4 Aquifer management plan formulation 2 1.3 Approach and methodology 2 1.4 Area details 2-4 1.5Data availability and data adequacy before conducting aquifer mapping 4-6 1.6 Data gap analysis and data generation 6 1.6.1 Data gap analysis 6 1.6.2 Recommendation on data generation 6 1.7 Rainfall distribution 7 1.8 Physiography 7-8 1.9 Geomorphology 8 1.10 Land use 9-10 1.11Soil 11 1.12 Drainage 11-12 1.13 Agriculture 13-14 1.14 Irrigation 14 1.15 Irrigation projects: Major, Medium and Minor 15-16 1.16 Ponds, tanks and other water conservation structures 16 1.17 Cropping pattern 16-17 1.18 Prevailing water conservation/recharge practices 17 1.19 General geology 18-19 1.20 Sub surface geology 19-20 2. -

Tripura Human Development Report II

Tripura Human Development Report II Pratichi Institute Pratichi (India) Trust 2018 2 GLIMPSES OF THE STUDY Contributory Authors Sabir Ahamed Ratan Ghosh Toa Bagchi Amitava Gupta Indraneel Bhowmik Manabi Majumdar Anirban Chattapadhyay Sangram Mukherjee Joyanta Choudhury Kumar Rana Joyeeta Dey Manabesh Sarkar Arijita Dutta Pia Sen Dilip Ghosh Editors Manabi Majumdar, Sangram Mukherjee, Kumar Rana and Manabesh Sarkar Field Research Sabir Ahamed Mukhlesur Rahaman Gain Toa Bagchi Dilip Ghosh Susmita Bandyopadhyay Sangram Mukherjee Runa Basu Swagata Nandi Subhra Bhattacharjee Piyali Pal Subhra Das Kumar Rana Joyeeta Dey Manabesh Sarkar Tanmoy Dutta Pia Sen Arijita Dutta Photo Courtesy Pratichi Research Team Logistical Support Dinesh Bhat Saumik Mukherjee Piuli Chakraborty Sumanta Paul TRIPURA HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORT II 3 4 GLIMPSES OF THE STUDY FOREWORD Amartya Sen India is a country of enormous diversity, and there is a great deal for us to learn from the varying experiences and achievements of the different regions. Tripura’s accomplishments in advancing human development have many distinguishing features which separate it out from much of the rest of India. An understanding of the special successes of Tripura is important for the people of Tripura, but – going beyond that – there are lessons here for the rest of India in appreciating what this small state has been able to achieve, particularly given the adverse circumstances that had to be overcome. Among the adversities that had to be addressed, perhaps the most important is the gigantic influx of refugees into this tiny state at the time of the partition of India in 1947 and again during the turmoil in East Pakistan preceding the formation of Bangladesh in 1971. -

List of School Under South Tripura District

List of School under South Tripura District Sl No Block Name School Name School Management 1 BAGAFA WEST BAGAFA J.B SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 2 BAGAFA NAGDA PARA S.B State Govt. Managed 3 BAGAFA WEST BAGAFA H.S SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 4 BAGAFA UTTAR KANCHANNAGAR S.B SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 5 BAGAFA SANTI COL. S.B SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 6 BAGAFA BAGAFA ASRAM H.S SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 7 BAGAFA KALACHARA HIGH SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 8 BAGAFA PADMA MOHAN R.P. S.B SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 9 BAGAFA KHEMANANDATILLA J.B SCHOOL TTAADC Managed 10 BAGAFA KALA LOWGONG J.B SCHOOL TTAADC Managed 11 BAGAFA ISLAMIA QURANIA MADRASSA SPQEM MADRASSA 12 BAGAFA ASRAM COL. J.B SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 13 BAGAFA RADHA KISHORE GANJ S.B. State Govt. Managed 14 BAGAFA KAMANI DAS PARA J.B. SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 15 BAGAFA ASWINI TRIPURA PARA J.B SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 16 BAGAFA PURNAJOY R.P. J.B SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 17 BAGAFA GARDHANG S.B SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 18 BAGAFA PRATI PRASAD R.P. J.B SCHOOL TTAADC Managed 19 BAGAFA PASCHIM KATHALIACHARA J.B. State Govt. Managed 20 BAGAFA RAJ PRASAD CHOW. MEMORIAL HIGH SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 21 BAGAFA ALLOYCHARRA J.B SCHOOL TTAADC Managed 22 BAGAFA GANGARAI PARA J.B SCHOOL TTAADC Managed 23 BAGAFA KIRI CHANDRA PARA J.B SCHOOL TTAADC Managed 24 BAGAFA TAUCHRAICHA CHOW PARA J.B TTAADC Managed 25 BAGAFA TWIKORMO HS SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 26 BAGAFA GANGARAI S.B SCHOOL State Govt. -

P:Tp:Lg9lv- 21 Dr

Government of TriPura O/o the Mission Director, National Health Mission, Tripura & Member Secretary, State AYUSH Mission, Tripura Palace Com pound, Asa rta la, Tri pu ra (West)-799001 O_R-D E-R The Regional Research Institute for Homoeopathy, Khumulwng, Tripura (West) under Central (two) Council for Research in Homoeopathy, Ministry of AYUSH, Govt. of India is going to organize 02 days Continued Medical Education (CME) Programme for uplifting the medical knowledge of Homoeo (West) doctors on 30ft & 31"1January, 2020 atRegional Research Institute (H), Khumulwng, Tripura at 9.30 A.M. The theme of CME is 'Scope of Homoeopathy in the Prevention & Treatment of Malaria and other vector bome diseases prevalent in Tripura' Therefore, the bellow mentioned Medical Officers (AYUSH) Homoeo under State Health & Family Welfare Society under NHM, Tripura are hereby directed to remain present on scheduled date, time and venue. sl. Date & Time Name of the Participants Designation Place of Posting No 1 Dr.Shreyasee Choud hury M.O (Homoeo) Bamutia PHC Ghatak 2 Dr. Chandan Debnath M.O (Homoeo) Nandannagar UPHC J Dr.Mita Das M.O (Homoeo) Ranibazar PHC 4 Dr.Sabari Goswami M.O (Homoeo) Asrampara UPHC 5 Dr. Somnath Reang M.O (Homoeo) Lefunga PHC 6 Dr. Jyotilal Debbarma M.O (Homoeo) l'r/landai PHC 7 Dr.Sukhendu Nath M.O (Homoeo) O/o CMO West M.O (Homoeo) Mohanpur CHC 30th & 31't 8 Dr.KakoliGope January, 9 Dr. Dipan Sankar Dey M.O (Homoeo) Kanchanmala PHC 2020 10 Dr.Tania Tilak M.O (Homoeo) Gandhigram PHC 11 Dr.Anindita Saha M.O (Homoeo) Jirania CHC t2 Dr. -

Memorandum of Settlement Between the Tripura State Government and All Tripura Tribal Force (ATTF)

Memorandum of Settlement between the Tripura State Government and All Tripura Tribal Force (ATTF) 23 August 1993 PREAMBLE: Where as the government of Tripura have been making concerned efforts to bring about an effective settlement of the problems of the tribal who are presently minority in Tripura an attempt have been made on a continuing basis to usher in peace and harmony in areas in which disturbed conditions have prevailed for long. AND Whereas All Tripura Tribal Force have given a clear indication that they would like to give up the path of armed struggle and would like to resume a normal life and they have decided to abandon the path of violence and to seek solutions to their problems within the framework of the Constitution of India and, therefore, they have responded positively to the appeals made by the Government of Tripura to join the mainstream and to help in the cause of building a prosperous Tripura AND Whereas on a series of discussions between the parties here to and based on such discussions it has been mutually agreed by and between the parties hereto that the FIRST ATTF shall give up the path of violence and surrender to the Other Party the Government of Tripura along with all their arms and ammunition ending their underground activities and the Governor of Tripura will provide some economic package and financial benefits and facilities hereafter provided 2. (B). Action is taken against foreign Nationals: - Action would be taken in respect of sending back all Bangladesh foreign nationals who have come to Tripura after 25 th March, 1971 and are not in possession of valid documents authorizing their presence in Tripura. -

2021081046.Pdf

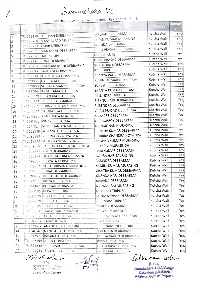

Samuxchana Vc Biock Kutcha house beneficiary list under Kakraban PD Answe Father Category APSWANI DEBBARMA TR1153198 SUBHASH DEBBARMA Kutcha Wall Yes RATAN KUMAR MURASING TR1128768 MANGALPAD MURASING Kutcha Wall Yes TR1128773 AMAR DEBBARMA ANANDA DEBBARMA Kutcha Wall Yes GUU PRASAD DEBBARMA Yes TR1177025 |MANYA LAL DEBBARMA Kutcha Wall TR1177028 HALEM MIA MNOHAR ALI Kutcha Wal Yes GURU PRASAD DEBBARMA Kutcha Nall TR1212148 SUNIL DEBBARMA Yes SURENDRA DEBBARMA Yes TR1128767 CHANDRA MANI DEBBARMA Kutcha Wall TR1235047 SADHANI DEBBARMA RABI TRIPURA Kutcha Wall Yes Kutcha Wall Yes TR1212144 JOY MOHAN DEBBARMA ARANYA PADA DEBBARMA RUHINI KUMAR DEB8ARMA Kutcha Wall Yes 10 TR1279857 HARIPADA DEBBARMA 11 TRL279860 SURJAYA MANIK DEBBARMA SURESH DEBBARMA Kutcha Wall Yes SHANTA KUMAR TRIPURA Kutcha Wall Yes 12 TR1200564 KRISHNAMANI TRIPURA 1258729 BIRAN MANI TRIPURA MALINDRA TRIPURA Kutcha Wall Yes Kutcha Wall 14 TR1165123 SURESH DEBBARMA BISHNU HARI DEBBARMA Yes 128769 PURNA MOHAN DEBBARMA SURENDRA DEBBARMA Kutcha Wall 1246344 GOURANGA DEBBARMA GURU PRASAD DEBBARMA Kutcha Wali Yes 17 RL140 83 KANTI BALA NOATIA SAHADEB DEBBARMA Kutcha Wa!l Yes 18 290885 BINAY DEBBARMA HACHUBROY DEBBARMA Kutcha Wali Yes 77024 SUKHCHANDRA MURASING MANMOHAN MURASING Kutcha Wall es 20 T1188838 SUMANGAL DEBBARMA JAINTHA KUMAR DEBBARMA Kutcha Wall Yes 2 T290883 PURRNARAY NOYATIYA DURRBA CHANDRA NOYATIYA Kutcha Wall Yes 212143 SHUKURAN!MURASING KRISHNA KUMAR MURASING Kutcha Wall Yes 279859 BAISHAKH LAKKHI MURASINGH PATHRAI MURASINGH Kutcha Wall Yes 128771 PULIN DEBBARMA -

Tripura's Tryst with Literacy

ISSN (Online) - 2349-8846 Tripura's Tryst with Literacy GORKY CHAKRABORTY, SUBHANIL CHOWDHURY Vol. 48, Issue No. 42, 19 Oct, 2013 Subhanil Chowdhury ([email protected]) and Gorky Chakraborty ([email protected]) teach at the Institute of Development Studies, Kolkata Tripura’s achievement in ensuring near full literacy is a consequence of initiatives taken at the level of governance, peoples’ participation and political will. As the public discourse today scrutinises the “development model” of the state of Gujarat ever so furiously, a significant milestone achieved by a small state in the much ignored North-East curiously has been given little coverage to. Tripura has become the most literate state in the country overtaking Kerala (itself, the owner of another “model” and a success story in social development). Manik Sarkar, the Chief Minister of Tripura in a press conference stated that as on date the literacy rate in the state was 94.65%. He also pointed out that Tripura is still short of attaining full literacy which the government will try and achieve soon (The Hindu, 9 September 2013). This achievement of Tripura shows how initiatives at the level of governance, peoples’ participation and political will can ensure education for all. Improvement in Literacy The remarkable improvement of Tripura in literacy is shown in the following table, along with other north-eastern states (and others that have been in the limelight recently). Table 1: Literacy Rates in Tripura and Other States State 1991 2001 2011 Tripura 60.44 73.19 87.75 Arunachal 41.59 54.34 66.95 Pradesh Nagaland 61.65 66.59 80.11 Manipur 59.89 70.53 79.85 Mizoram 82.26 88.80 91.58 Meghalaya 49.1 62.56 75.48 Assam 52.89 63.25 73.18 Kerala 89.81 90.86 93.91 Gujarat 61.29 69.14 79.31 ISSN (Online) - 2349-8846 Source: Economic Survey, Government of India, 2012-13 Table 1 shows that Tripura has increased its literacy rate by around 27 percentage points between 1991 and 2011. -

List of Applicants to Be Appeared Before the Interview For

List of Applicants to be appeared before the interview for undergoing EDP under National Mission for Food Processing (NMFP) of Ministry of Food Processing (MoFPI), Govt. of India. District: West Tripura Re SL. Name & Address Sub-Div. Category Venue Date Time mar No. ks W001 Sri Ratan debbarma, S/O, Sri Rabi Debbarma, Mohanpur ST SOFED, 19/09/2014 10.30 Vill: Gamcha Kobra Para, P.O: BodhjungNagar, Indranagar, AM Lefunga, Mohanpur, Tripura(w), Pin.No: 799210 Agartala W002 Sri Gitosh Debbarma, S/O, Sri Girendra Mohanpur S.T SOFED, 19/09/2014 10.30 Debbarma, Vill: Sarat Chowdhury Para, P.O: Indranagar, AM Darogamura, Sidhai, Mohanpur, Tripura(w), Agartala Pin.No: 799212 W003 Sri Bitu Debbarma, S/O, SriBrajendra Debbarma, Mohanpur S.T SOFED, 19/09/2014 10.30 Vill: Gamcha Kobra Para, P.O: Bodhjungnagar, Indranagar, AM Lefunga, Mohanpur, Tripura(W), Pin.No: 799120 Agartala W004 Sri Sajal Debbarma, S/O, sri Upendra Debbarma, Mohanpur S.T SOFED, 19/09/2014 10.30 Vill: Bhagaban Chowdhurypara, P.O: Indranagar, AM Bodhjangnagar, , Lefunga, Mohanpur, Agartala Tripura(W), Pin.No: 799210 W005 Sri Dinesh Debbarma, S/O, Sri Jitendra Mohanpur ST SOFED, 19/09/2014 10.30 Debbarma, Vill: Khampar Para, P.O: Bodhjung Indranagar, AM Nagar, Lefunga, Mohanpur, Tripura(W), Pin.No: Agartala 799210 W006 Sri Utpal Debbarma, S/O, Sri Anil Debbarma, Mohanpur ST SOFED, 19/09/2014 10.30 Vill: Radharambari, P.O: Uttardas Garia, Sidhai, Indranagar, AM Mohanpur, Tripura(W), Pin.No: 799212 Agartala W007 Sri Sanjoy Debbarma, S/O, Sri Phanil Debbarma, Mohanpur ST SOFED, 19/09/2014 -

The Executive Engineer, Kumarghat Division, PWD

FORMAT – A GOVERNMENT OF TRIPURA (For publication in the PUBLIC WORKS DEPARTMENT Local Newspapers and Websites) PRESS NOTICE INVITING e-TENDER NO: 21/EE/KD/2018-19 dated 31/01/2019 The Executive Engineer, Kumarghat Division, PWD(R&B), Kumarghat, Unakoti District, Tripura invites on behalf of the ‘Governor of Tripura’ percentage rate e-tender from the Central & State public sector undertaking / enterprise and eligible Bidders /Firms/Agencies of appropriate class registered with PWD/TTAADC/MES/CPWD/Railway/Other State PWD up to 15.00 Hrs. on 21.02.2019 for the following work:- NAME OF THE WORK BID COST SL SL NO MONEY BIDDER EARNEST EARNEST CLASS OF CLASS TIME FOR FOR TIME FOR TIME DOCUMENT DOCUMENT DOCUMENT ESTIMATED ESTIMATED AND BIDDING BIDDING AND COMPLETION APPLICATION AND BIDING AT AT BIDING AND OF OPENING OF OF OPENING OF DOWNLOADING DOWNLOADING DOWNLOADING LAST DATE AND AND DATE LAST TIME AND DATE DATE AND TIME FDR of road from AA road to Truck Syndicate and AA road to Ratiabari under Kumarghat Sub-division during the year 1 2018-19/SH: Patch repairing by providing soling, metalling, carpeting, seal coat, etc. 21.02.2019 21.02.2019 Rs.14,538.00 Up to15.00 Hrs Hrs Up to15.00 3 (three) months 3 (three) At 16.00 Hrs on on Hrs 16.00 At Rs. 14, 53, 813.00 53, Rs. 14, No: 41/EE/KD/2018-19. Mtc of the road from NEC road near College Chowmuhani to Ambedkar College (L-1.00 Km) during the year 2017-18/SH: Patch Appropriate Class Appropriate 2 metalling, grouting, patch carpeting and seal coating etc https://tripuratenders.gov.in 21.02.2019 21.02.2019 Rs.19,440.00 Up to15.00 Hrs Hrs Up to15.00 3 (three) months 3 (three) At 16.00 Hrs on on Hrs 16.00 At No: 42/SE (I)/KGT/2017-19. -

Oil and Natural Gas Corporation Limited

OIL AND NATURAL GAS CORPORATION LIMITED ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT/ ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR Conversion of 37 Exploration Wells & laying of Associated Flowlines, Involving Construction of Well Manifold At Kunjaban And Sundalbari And Pipeline At District North Tripura [ToR Letter: J-11011/60/2017-IA.II(I) dated 31st May 2017] [ToR Amendment Letter: J-11011/60/2017-IA II(I) dated 20th December 2018] [Study Period: 1st October 2018 to 31st December 2018] [Schedule 1 (b) Category–“A” as per EIA Notification 2006] APPLICANT CONSULTANT Oil and Natural Gas Corporation ECO CHEM SALES & Limited SERVICES ONGC, 4th Floor, Tower A, Pandit Deendayal Office floor, Ashoka Pavilion Upadhyay Urja Bhavan, Plot No 5, Vasant ‟A‟, New Civil Road, Surat, Kunj, Nelson Mandela Marg, New Delhi 395001. (QCI/NABET Accredited 110070. No. NABET/EIA/2023/RA 0181) E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Contact No: 0 98682 82200 Contact No: +912612231630 April – 2021 Doc. No: 2018_ECSS_EIAI2_1800007 EIA/EMP Report For Conversion of 37 Exploration Wells & laying of Associated Flowlines, involving construction of Well Manifold at Kunjaban & Sundalbari and Pipeline by Oil and Natural Gas Corporation Limited (ONGC) UNDERTAKING BY PROJECT PROPONENT Eco Chem Sales & Services, Surat 2018_ECSS_EIAI2_1800007 i EIA/EMP Report For Conversion of 37 Exploration Wells & laying of Associated Flowlines, involving construction of Well Manifold at Kunjaban & Sundalbari and Pipeline by Oil and Natural Gas Corporation Limited (ONGC) UNDERTAKING BY CONSULTANT