MISTRAL by Bob Morrill

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“The Answer to Laundry in Outer Space”: the Rise and Fall of The

Archived thesis/research paper/faculty publication from the University of North Carolina at Asheville’s NC DOCKS Institutional Repository: http://libres.uncg.edu/ir/unca/ University of North Carolina Asheville “The Answer to Laundry in Outer Space”: The Rise and Fall of the Paper Dress in 1960s American Fashion A Senior Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Department of History In Candidacy for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts in History By Virginia Knight Asheville, North Carolina November 2014 1 A woman stands in front of a mirror in a dressing room, a sales assistant by her side. The sales assistant, with arms full of clothing and a tape measure around her neck, beams at the woman, who is looking at her reflection with a confused stare. The woman is wearing what from the front appears to be a normal, knee-length floral dress. However, the mirror behind her reveals that the “dress” is actually a flimsy sheet of paper that is taped onto the woman and leaves her back-half exposed. The caption reads: “So these are the disposable paper dresses I’ve been reading about?” This newspaper cartoon pokes fun at one of the most defining fashion trends in American history: the paper dress of the late 1960s.1 In 1966, the American Scott Paper Company created a marketing campaign where customers sent in a coupon and shipping money to receive a dress made of a cellulose material called “Dura-Weave.” The coupon came with paper towels, and what began as a way to market Scott’s paper products became a unique trend of American fashion in the late 1960s. -

Fashion : the Essential Visual Guide to the World of Style Pdf, Epub, Ebook

FASHION : THE ESSENTIAL VISUAL GUIDE TO THE WORLD OF STYLE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Karen Homer | 192 pages | 03 May 2018 | AURUM PRESS | 9781781316955 | English | London, United Kingdom Fashion : The Essential Visual Guide to the World of Style PDF Book A style of knitting in which textures of crossing layers form a twisted rope look, the cable knit is classic cozy. Maxi — A long skirt calling it quits near the ankle, the maxi is perfect for a day at the park or a night on the town. Get A Copy. Long and loose with wide sleeves and the ability to be tied with a sash, the kimono is a cozy cool must have, both beautiful and timeless. Bomber — Also known as a flight jacket, the bomber was originally created for pilots, and has become an industry hit since. Wrap Skirt — Formed by either actually wrapping excess fabric around the body or creating the illusion with a twist of cloth, the wrap skirt style evokes a beachy cover-up or Grecian goddess. Vintage and antique clothing is steeped in history and can open you up to a whole world of yesterday that you were unaware of till now. Skort — This two-in-one skirt and shorts combo utilizes a front panel to give shorts the appearance of a skirt. Notify me of new posts via email. Fashion Travel Restaurants Music. Visit some of our favorite menswear stores. Throughout the show, we see various types of physically and mentally strong women. Lists with This Book. Readers also enjoyed. This slideshow requires JavaScript. Arguably no other character in television history has rocked the fitted crop top as awesomely as Missandei, who frequently pairs these with high-waisted skirts or wide trousers that allow her to move comfortably and freely. -

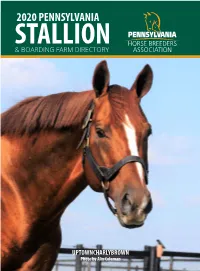

Online-2020-Stallion-Directory-File.Pdf

2020 PENNSYLVANIA STALLION & BOARDING FARM DIRECTORY UPTOWNCHARLYBROWN Photo by Alix Coleman 2020 PENNSYLVANIA STALLION & BOARDING FARM DIRECTORY Pennsylvania Horse Contents Breeders Association Pennsylvania, An Elite Breeding Program 4 Breeding Fund FAQ’s 6-7 Officers and Directors PA-Bred Earning Potential 8-9 President: Gregory C. Newell PE Stallion Roster 10-11 Vice President: Robert Graham Stallion Farm Directory 12-13 Secretary: Douglas Black Domicile Farm Directory 14-15 Treasurer: David Charlton Directors: Richard D. Abbott Front Cover Image: Uptowncharlybrown Elizabeth B. Barr Front Cover Photo Credit: Alix Coleman Glenn Brok Peter Giangiulio, Esq. Kate Goldenberg Roger E. Legg, Esq. PHBA Office Staff Deanna Manfredi Elizabeth Merryman Joanne Adams (Bookkeeper) Henry Nothhaft Jennifer Corado (Office Manager) Thomas Reigle Wendi Graham (Racing/Stallion Manager) Dr. Dale Schilling, VMD Jennifer Poorman (Graphic Designer) Charles Zachney Robert Weber (IT Manager) Executive Secretary: Brian N. Sanfratello Assistant Executive Secretary: Vicky Schowe Statistics provided herein are compiled by Pennsylvania Horse Contact Us Breeders Association from data supplied by Stallion and Farm Owners. Data provided or compiled generally is accurate, but 701 East Baltimore Pike, Suite E occasionally errors and omissions occur as a result of incorrect Kennett Square PA 19348 data received from others, mistakes in processing, and other Website: pabred.com causes. Phone: 610.444.1050 The PHBA disclaims responsibility for the consequences, if any, of Email: [email protected] such errors but would appreciate it being called to its attention. This publication will not be sold and can be obtained, at no cost, by visiting our website at www.pabred.com or contacting our office at 610.444.1050. -

Insull on Stand, Asserts Britain Wanted Him There

\. THE WKATHKK Foraeaat e ( V. S. WeatiMi AVUUOB OAILT cmCUlATION Hartford fcw tkm meirik e< Oeteber. 18M Fhir_________eeldm, wHh Mgfct . *• heavy froct oa the eoaat aad heavy 5,442 ta the Intertor tonight, FHday fkir. Member e< the Audit ButM of OlreiilathMW (TWELVE PAGES) PRICE THREE CEN Tf' AdvorttsUM an Page M.) MANCHESTER. CONN„ A.&P.LEADERS .Hungrer Marchers Felled In Battle With Police JAPANESE ACT INSULL ON STAND, LOCAL WOMAN KILLED AS SHE IN CONFERENCE TO EFFECT AN ASSERTS BRITAIN OIL MONOPOLY CRO^ROAD ON P R E P L A N WANTED HIM THERE Despite Protests of I) S,, Mrs. Daniel J. SoDban Dies Manasers of the Cleveland Britain and Holland, Man- Utilities Magnate Dedaret As She Is HH by Ante Stores Called to New jE w im iioP E iT y chonkno to Go Ahead — Stanley Baldwin Offered Driven by Janies Maher, York« to Talk Over the SOUTOENOMI Complications Foreseen. Him an Important Post Sitnation. Was Seeking (hO i Bat He Tamed It Down to Tokyo. Nov. 1.— (A P )—The Man- Local Real Estate Promoter Mr*. BUzabeth T a n n ^ Sullivan, New York, Nov. 1.— (A P )—Offi- choukuo government. It was learn- 80, wife of Daniel J. Sullivan, of 418 cials o f Cleveland stores of the ed today, hae already moved to ef- Gets Land for New Tract Remam m U. S. Great AUantlc 'A PadAc Tea Com- .'East Cfenter street, was fatally In- fect an oil monopoly, despite repre- pany were enroute to New York to' sentations by toe United States, jured last night when ehe was at the Green. -

Augusta Auction Company Historic Fashion & Textile

AUGUSTA AUCTION COMPANY HISTORIC FASHION & TEXTILE AUCTION MAY 9, 2017 STURBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS 1 TRAINED CHARMEUSE EVENING GOWN, c. 1912 Cream silk charmeuse w/ vine & blossom pattern, empire bodice w/ silk lace & sequin overlay, B to 38", W 28", L 53"-67", (small holes to lace, minor thread pulls) very good. MCNY 2 DECO LAME EVENING GOWN, LATE 1920s Black silk satin, pewter lame in Deco pattern, B to 36", Low W to 38", L 44"-51", excellent. MCNY 3 TWO EMBELLISHED EVENING GOWNS, 1930s 1 purple silk chiffon, attached lace trimmed cape, rhinestone bands to back & on belt, B to 38", W to 31", L 58", (small stains to F, few holes on tiers) fair; 1 rose taffeta underdress overlaid w/ copper tulle & green silk flounce, CB tulle drape, silk ribbon floral trim, B to 38", W 28", L 60", NY label "Blanche Yovin", (holes to net, long light hem stains) fair- good. MCNY 4 RHINESTONE & VELVET EVENING DRESS, c. 1924 Sapphire velvet studded w/ rhinestones, lame under bodice, B 32", H 36", L 50"-53", (missing stones, lame pulls, pink lining added & stained, shoulder straps pinned to shorten for photo) very good. MCNY 5 MOLYNEUX COUTURE & GUGGENHEIM GOWNS, 1930-1950s Both black silk & labeled: 1 late 30s ribbed crepe, "Molyneux", couture tape "11415", surplice bodice & button back, B to 40", W to 34", H to 38", L 58", yellow & black ikat sash included, (1 missing button) excellent; "Mingolini Guggenheim Roma", strapless multi-layered sheath, B 34", W 23", H 35", CL 46"-50", (CF seam unprofessionally taken in by hand, zipper needs replacing) very good. -

Outside Covers

YARRADALE STUD 2013 YEARLING SALE 12.00PM SUNDAY 19 MAY O’BRIEN ROAD, GIDGEGANNUP, WESTERN AUSTRALIA FROST GIANT HE’S COMING New to Western Australia in 2013 A son of GIANT’S CAUSEWAY, just like champion sire, SHAMARDAL. From the STORM CAT sireline, just like successful WA sire MOSAYTER - sire of MR MOET, TRAVINATOR, ROMAN KNOWS etc This durable, tough Group 1 winner, won from 2 years through to 5 years and was a top class performer on both turf and dirt. In his freshman year in 2012 he was fourth leading first crop sire in America!! (ahead of Big Brown, Street Boss etc) • Ranked number 1 by % winners to runners – 80% • Ranked number 1 by Stakes horses to runners – 27% • All time leading money earnings for a first crop sire in America’s North East. With his first crop of 2YO’s in 2012 he sired: • 15 runners for 12 individual 2YO winners! • 4 of those were 2YO stakes horses! • Average earnings of over $50,000 for every 2YO! Continuing on from what has been a wonderful year on the racetrack for our Yarradale Stud graduates, we take great pleasure in presenting to you our 2013 Yarradale Stud Yearling Sale catalogue. After four successful editions of the on farm sale, we are now seeing some fantastic results and stories coming out of these sales. Not only have the previous on farm sales been a great day out with wonderful crowds in attendance, these sales are now proving to be a great source of winners. Obviously our aim is to sell yearlings that go on and perform and we have been thrilled to see the graduates of our previous sales really hitting their straps in recent times. -

Pwc in the Caribbean 2018 © 2018 Pwc

PwC in the Caribbean 2018 © 2018 PwC. All rights reserved. PwC refers to the PwC network and/or one or more of its member firms, each of which is a separate legal entity. Please see www.pwc.com/structure for further details. Serving the Caribbean with purpose To say the least, 2017 was a busy year! Looking back, our of services in every line of service and business unit. By economies had their ups and downs and the financial continuing to fortify the core of our business, we have markets experienced significant swings. 2017 also saw an positioned ourselves to look to 2018 with confidence and introduction of many new and inspirational opportunities, optimism. as well as political and economic changes – sweeping The theme for 2018 is “what’s our potential”. This is a year across the globe. in which we want to set records; record growth, record 2017 – A year of uncertainties, inspiration and change client service, record brand recognition, and at the same maintain our status of being employer of choice. We From a new President in the United States to artificial surveyed our people and clients in 2017 about how PwC intelligence, which will soon drive the way leading firms can reach its full potential, we listened, made appropriate provide everything from customer service to investment changes based on many of your suggestions and we believe advice; from blockchain, and its ability to store information these changes will make a difference. data on distributed ledgers without a central clearinghouse to cyber security that assists our clients hold off threats These improvements will make PwC in the Caribbean that come from multiple directions to risk management, achieve the goals to which we all aspire, by working culture, ethics and trust. -

Pastorale Nureyev Park Appeal Dixie Union Dixieland Band

Consigned by Woodfort Stud 401 401 Gone West Zafonic Iffraaj (GB) Zaizafon BAY FILLY (IRE) Nureyev April 8th, 2011 Pastorale Park Appeal (Third Produce) Dixieland Band Dixie Union Hams (USA) She's Tops (2003) Desert Wine Desert Victress Elegant Victress E.B.F. Nominated. B.C. Nominated. 1st dam HAMS (USA): placed twice at 3; dam of 2 previous foals; 2 runners; 2 winners: Super Market (IRE) (08 f. by Refuse To Bend (IRE)): 4 wins at 2 in Italy. Dixie's Dream (IRE) (09 c. by Hawk Wing (USA)): 2 wins at 2 and 3, 2012 and placed 5 times. 2nd dam DESERT VICTRESS (USA): placed twice at 2 and 3; also winner at 3 in U.S.A. and placed 3 times; dam of 10 foals; 9 runners; 3 winners inc.: DESERT DIGGER (USA) (f. by Mining (USA)): winner at 2 in U.S.A. and £99,649 viz. Sorrento S., Gr.2, placed 5 times inc. 2nd Del Mar Debutante S., Gr.2 and 3rd Princess S., Gr.2; dam of winners inc.: SIRMIONE (USA): won HBPA H. and 2nd Ellis Park Turf S., L. Back Packer (USA): winner in U.S.A., 2nd Transylvania S., L. 3rd dam ELEGANT VICTRESS (CAN) (by Sir Ivor (USA)): 3 wins at 3 in U.S.A. and placed 5 times; dam of 12 foals; 10 runners; 7 winners inc.: EXPLICIT (USA): 6 wins in U.S.A. and £404,504 inc. True North Breeders' Cup H., Gr.2, Count Fleet Sprint H., Gr.3, Pelleteri Breeders' Cup H., L. -

Preakness Stakes .Fifty-Three Fillies Have Competed in the Preakness with Start in 1873: Rfive Crossing the Line First The

THE PREAKNESS Table of Contents (Preakness Section) History . .P-3 All-Time Starters . P-31. Owners . P-41 Trainers . P-45 Jockeys . P-55 Preakness Charts . P-63. Triple Crown . P-91. PREAKNESS HISTORY PREAKNESS FACTS & FIGURES RIDING & SADDLING: WOMEN & THE MIDDLE JEWEL: wo people have ridden and sad- dled Preakness winners . Louis J . RIDERS: Schaefer won the 1929 Preakness Patricia Cooksey 1985 Tajawa 6th T Andrea Seefeldt 1994 Looming 7th aboard Dr . Freeland and in 1939, ten years later saddled Challedon to victory . Rosie Napravnik 2013 Mylute 3rd John Longden duplicated the feat, win- TRAINERS: ning the 1943 Preakness astride Count Judy Johnson 1968 Sir Beau 7th Fleet and saddling Majestic Prince, the Judith Zouck 1980 Samoyed 6th victor in 1969 . Nancy Heil 1990 Fighting Notion 5th Shelly Riley 1992 Casual Lies 3rd AFRICAN-AMERICAN Dean Gaudet 1992 Speakerphone 14th RIDERS: Penny Lewis 1993 Hegar 9th Cynthia Reese 1996 In Contention 6th even African-American riders have Jean Rofe 1998 Silver’s Prospect 10th had Preakness mounts, including Jennifer Pederson 2001 Griffinite 5th two who visited the winners’ circle . S 2003 New York Hero 6th George “Spider” Anderson won the 1889 Preakness aboard Buddhist .Willie Simms 2004 Song of the Sword 9th had two mounts, including a victory in Nancy Alberts 2002 Magic Weisner 2nd the 1898 Preakness with Sly Fox “Pike”. Lisa Lewis 2003 Kissin Saint 10th Barnes was second with Philosophy in Kristin Mulhall 2004 Imperialism 5th 1890, while the third and fourth place Linda Albert 2004 Water Cannon 10th finishers in the 1896 Preakness were Kathy Ritvo 2011 Mucho Macho Man 6th ridden by African-Americans (Alonzo Clayton—3rd with Intermission & Tony Note: Penny Lewis is the mother of Lisa Lewis Hamilton—4th on Cassette) .The final two to ride in the middle jewel are Wayne Barnett (Sparrowvon, 8th in 1985) and MARYLAND MY Kevin Krigger (Goldencents, 5th in 2013) . -

Magnetic Resonance Imaging Special

SPECIAL SEPTEMBER 2017 // MAGAZINE FOR MEDICAL & HEALTH PROFESSIONALS Magnetic Resonance Imaging special Women’s & Men’s Interviews Green Apple Health: Breast & with Toshiba Award for Prostate Imaging Medical’s Users Vantage Elan SPECIAL SEPTEMBER 2017 // MAGAZINE FOR MEDICAL & HEALTH PROFESSIONALS VISIONS Special: Magnetic Resonance Imaging Magnetic Resonance Imaging special Women’s & Men’s Interviews Green Apple Health: Breast & with Toshiba Award for Prostate Imaging Medical’s Users Vantage Elan VISIONS magazine is a publication of Toshiba Medical Europe and is offered free of charge to medical and health professionals. The mentioned products may not be available in other geographic regions. Please consult your Toshiba Medical representative sales office in case of any questions. No part of this publication may be reproduced in whole or in part, stored in an automated storage and retrieval system or transmitted in any manner whatsoever without written permission of the publisher. The opinions expressed in this publication are solely those of the authors and not necessarily those of Toshiba Medical. Toshiba Medical does not guarantee the accuracy or reliability of the information provided herein. Publisher Toshiba Medical Systems Europe B.V. Zilverstraat 1 NL-2718 RP Zoetermeer Tel.: +31 79 368 92 22 Fax: +31 79 368 94 44 Web: www.toshiba-medical.eu Email: [email protected] Editor-in-chief Jack Hoogendoorn ([email protected]) Editor Jacqueline de Graaf ([email protected]) Modality coordinator and reviewer MRI Martin de Jong Design & Layout Boerma Reclame (www.boermareclame.com) Printmanagement Het Staat Gedrukt (www.hetstaatgedrukt.nl) Text contributions and editing The Creative Practice (www.thecreativepractice.com) © 2017 by Toshiba Medical Europe All rights reserved ISSN 1617-2876 EDITORIAL Dear reader, In your hands you have a new and special edition of our VISIONS magazine, totally dedicated to Magnetic Resonance Imaging. -

Ulysses, Episode XII, "Cyclops"

I was just passing the time of day with old Troy of the D. M. P. at the corner of Arbour hill there and be damned but a bloody sweep came along and he near drove his gear into my eye. I turned around to let him have the weight of my tongue when who should I see dodging along Stony Batter only Joe Hynes. — Lo, Joe, says I. How are you blowing? Did you see that bloody chimneysweep near shove my eye out with his brush? — Soot’s luck, says Joe. Who’s the old ballocks you were taking to? — Old Troy, says I, was in the force. I’m on two minds not to give that fellow in charge for obstructing the thoroughfare with his brooms and ladders. — What are you doing round those parts? says Joe. — Devil a much, says I. There is a bloody big foxy thief beyond by the garrison church at the corner of Chicken Lane — old Troy was just giving me a wrinkle about him — lifted any God’s quantity of tea and sugar to pay three bob a week said he had a farm in the county Down off a hop of my thumb by the name of Moses Herzog over there near Heytesbury street. — Circumcised! says Joe. — Ay, says I. A bit off the top. An old plumber named Geraghty. I'm hanging on to his taw now for the past fortnight and I can't get a penny out of him. — That the lay you’re on now? says Joe. -

ALBUMS BARRY WHITE, "WHAT AM I GONNA DO with BLUE MAGIC, "LOVE HAS FOUND ITS WAY JOHN LENNON, "ROCK 'N' ROLL." '50S YOU" (Prod

DEDICATED TO THE NEEDS OF THE MUSIC RECORD INCUSTRY SLEEPERS ALBUMS BARRY WHITE, "WHAT AM I GONNA DO WITH BLUE MAGIC, "LOVE HAS FOUND ITS WAY JOHN LENNON, "ROCK 'N' ROLL." '50s YOU" (prod. by Barry White/Soul TO ME" (prod.by Baker,Harris, and'60schestnutsrevved up with Unitd. & Barry WhiteProd.)(Sa- Young/WMOT Prod. & BobbyEli) '70s savvy!Fast paced pleasers sat- Vette/January, BMI). In advance of (WMOT/Friday'sChild,BMI).The urate the Lennon/Spector produced set, his eagerly awaited fourth album, "Sideshow"men choosean up - which beats with fun fromstartto the White Knight of sensual soul tempo mood from their "Magic of finish. The entire album's boss, with the deliversatasteinsupersingles theBlue" album forarighteous niftiest nuggets being the Chuck Berry - fashion.He'sdoingmoregreat change of pace. Every ounce of their authored "You Can't Catch Me," Lee thingsinthe wake of currenthit bounce is weighted to provide them Dorsey's "Ya Ya" hit and "Be-Bop-A- string. 20th Century 2177. top pop and soul action. Atco 71::14. Lula." Apple SK -3419 (Capitol) (5.98). DIANA ROSS, "SORRY DOESN'T AILWAYS MAKE TAMIKO JONES, "TOUCH ME BABY (REACHING RETURN TO FOREVER FEATURING CHICK 1116111113FOICER IT RIGHT" (prod. by Michael Masser) OUT FOR YOUR LOVE)" (prod. by COREA, "NO MYSTERY." No whodunnits (Jobete,ASCAP;StoneDiamond, TamikoJones) (Bushka, ASCAP). here!This fabulous four man troupe BMI). Lyrical changes on the "Love Super song from JohnnyBristol's further establishes their barrier -break- Story" philosophy,country -tinged debut album helps the Jones gal ingcapabilitiesby transcending the with Masser-Holdridge arrange- to prove her solo power in an un- limitations of categorical classification ments, give Diana her first product deniably hit fashion.