Dades Personals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Guess What Or Who…

Over to You 2001/2002 Guess What or Who 2 – Countries Programmanus 01058/ra15 GUESS WHAT OR WHO… PART 2 – COUNTRIES Manus: Amy Bruford Producent: Claes Nordenskiöld Sändningsdatum: 15/1, 2002 Längd: 9'26 Music: "Guess What or Who… Theme Song – Introduction" (Red Hot Chili Peppers "I Like Dirt" and Public Enemy "Fight the Power") Leigh: Welcome to the second programme in our new series GUESS WHAT OR WHO … This time our theme is – COUNTRIES. You'll hear one person from our panel speak about a specific country, your job is to figure out which. Our panel consists of Solange… Solange: Hi. Leigh: …Sam… Sam: Hello. Leigh: …and Kaitlin. Kaitlin: Hi. Leigh: If you have the worksheet in front of you, you have four alternatives to choose from. If you don't, just write down your answer on a piece of paper. We'll give you the correct answers at the end of the programme. We'll describe eight different countries, so let's get started. Here's the first. Which country does SOLANGE describe? Solange: My mother actually comes from this country where they speak both English and Swahili. It's less than half the size of Sweden, but more than twice as many people live there. The capital is called Kampala, which is right on a large lake, Lake Victoria. The colours of the flag are black, red and yellow. Leigh: Which country was that: Uganda, Sudan, Zimbabwe or Nigeria? Write your answer next to number 1. 1 Over to You 2001/2002 Guess What or Who 2 – Countries Programmanus 01058/ra15 Music: Ikoce "Kec" Leigh: Now to the second question and our second country. -

Just the Right Song at Just the Right Time Music Ideas for Your Celebration Chart Toppin

JUST THE RIGHT SONG AT CHART TOPPIN‟ 1, 2 Step ....................................................................... Ciara JUST THE RIGHT TIME 24K Magic ........................................................... Bruno Mars You know that the music at your party will have a Baby ................................................................ Justin Bieber tremendous impact on the success of your event. We Bad Romance ..................................................... Lady Gaga know that it is so much more than just playing the Bang Bang ............................................................... Jessie J right songs. It‟s playing the right songs at the right Blurred Lines .................................................... Robin Thicke time. That skill will take a party from good to great Break Your Heart .................................. Taio Cruz & Ludacris every single time. That‟s what we want for you and Cake By The Ocean ................................................... DNCE California Girls ..................................................... Katie Perry your once in a lifetime celebration. Call Me Maybe .......................................... Carly Rae Jepson Can‟t Feel My Face .......................................... The Weeknd We succeed in this by taking the time to get to know Can‟t Stop The Feeling! ............................. Justin Timberlake you and your musical tastes. By the time your big day Cheap Thrills ................................................ Sia & Sean Paul arrives, we will completely -

The Art of Performance a Critical Anthology

THE ART OF PERFORMANCE A CRITICAL ANTHOLOGY edited by GREGORY BATTCOCK AND ROBERT NICKAS /ubu editions 2010 The Art of Performance A Critical Anthology 1984 Edited By: Gregory Battcock and Robert Nickas /ubueditions ubu.com/ubu This UbuWeb Edition edited by Lucia della Paolera 2010 2 The original edition was published by E.P. DUTTON, INC. NEW YORK For G. B. Copyright @ 1984 by the Estate of Gregory Battcock and Robert Nickas All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper or broadcast. Published in the United States by E. P. Dutton, Inc., 2 Park Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10016 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 79-53323 ISBN: 0-525-48039-0 Published simultaneously in Canada by Fitzhenry & Whiteside Limited, Toronto 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 First Edition Vito Acconci: "Notebook: On Activity and Performance." Reprinted from Art and Artists 6, no. 2 (May l97l), pp. 68-69, by permission of Art and Artists and the author. Russell Baker: "Observer: Seated One Day At the Cello." Reprinted from The New York Times, May 14, 1967, p. lOE, by permission of The New York Times. Copyright @ 1967 by The New York Times Company. -

Magnetic Resonance Imaging Special

SPECIAL SEPTEMBER 2017 // MAGAZINE FOR MEDICAL & HEALTH PROFESSIONALS Magnetic Resonance Imaging special Women’s & Men’s Interviews Green Apple Health: Breast & with Toshiba Award for Prostate Imaging Medical’s Users Vantage Elan SPECIAL SEPTEMBER 2017 // MAGAZINE FOR MEDICAL & HEALTH PROFESSIONALS VISIONS Special: Magnetic Resonance Imaging Magnetic Resonance Imaging special Women’s & Men’s Interviews Green Apple Health: Breast & with Toshiba Award for Prostate Imaging Medical’s Users Vantage Elan VISIONS magazine is a publication of Toshiba Medical Europe and is offered free of charge to medical and health professionals. The mentioned products may not be available in other geographic regions. Please consult your Toshiba Medical representative sales office in case of any questions. No part of this publication may be reproduced in whole or in part, stored in an automated storage and retrieval system or transmitted in any manner whatsoever without written permission of the publisher. The opinions expressed in this publication are solely those of the authors and not necessarily those of Toshiba Medical. Toshiba Medical does not guarantee the accuracy or reliability of the information provided herein. Publisher Toshiba Medical Systems Europe B.V. Zilverstraat 1 NL-2718 RP Zoetermeer Tel.: +31 79 368 92 22 Fax: +31 79 368 94 44 Web: www.toshiba-medical.eu Email: [email protected] Editor-in-chief Jack Hoogendoorn ([email protected]) Editor Jacqueline de Graaf ([email protected]) Modality coordinator and reviewer MRI Martin de Jong Design & Layout Boerma Reclame (www.boermareclame.com) Printmanagement Het Staat Gedrukt (www.hetstaatgedrukt.nl) Text contributions and editing The Creative Practice (www.thecreativepractice.com) © 2017 by Toshiba Medical Europe All rights reserved ISSN 1617-2876 EDITORIAL Dear reader, In your hands you have a new and special edition of our VISIONS magazine, totally dedicated to Magnetic Resonance Imaging. -

Mini-Mag N12

Bulletin de liaison Automne/Hiver 2012 mini-Mag N12 L'École de Berlin, entre mythe et réalité Par Frédéric Gerchambeau Revenons au tout début de l'histoire. Nous avons un rocker psychédélique en mal de reconnaissance de son jeu guitaristique, un batteur apocalyptique passionné de musique classique, un ex-batteur de jazz féru de rythmes africains et un organiste moyennement doué et surtout dilettante. Difficile d'espérer, a priori, que ces quatre personnages révolutionnent quoi que ce soit concernant la musique. Et pourtant. Mais ils ne l'auraient pas fait sans un sérieux coup de pouce. De qui donc ? D'un musicien d'origine suisse généralement parfaitement ignoré dans ce contexte. Je veux parler de Thomas Kessler. Car la plupart des musiciens qui ont pris part à l'aventure de ce que je conte ici ont longuement assisté aux cours de composition dispensés au Conservatoire de Berlin par le compositeur de musique contemporaine Thomas Kessler. Celui-ci, très soucieux de contribuer à la maturation artistique des jeunes musiciens berlinois qui assistaient à ses cours, ne se contentait pas de leur enseigner sa déjà longue expérience en Quand on évoque l'Ecole de Berlin, on sait parfaitement de quoi on parle. On parle matière de musique expérimentale. Il a mis, en effet, à leur de séquences hypnotiques, de solos envoûtants et souvent orientalisants, de sons disposition un véritable studio où ceux-ci pouvaient répéter étranges et de nappes éthérées, le tout contenu dans de longues plages musicales librement et s'aventurer à loisir dans toutes sortes de aux parfums d'ailleurs et d'infini. -

On Music Angels God Only Knows

On Music Angels God Only Knows David Milo Kirkham Yester-Me, Yester-You, Yesterday The trek from my office at the Air Force Academy history department to the faculty parking lot was long enough—about a ten-minute walk—suf- ficient time for some substantive thinking. One winter evening in about 1992, as I made the walk, my Comparative Revolutions course weighed on my mind. As I pondered how I might introduce the next day’s discus- sion on causes of revolutions, I climbed into my 1987 red Dodge Colt more out of habit than deliberation. At the turn of the ignition key, the radio’s boom broke my reverie and jarred me back to the reality of my immediate surroundings. “Where did it go, that yester-glow, . yester-me, yester-you,” rang out the soulful tenor voice of Stevie Wonder from Colorado Springs’ sole oldies station. A decent song, I thought, ready for a musical interlude to my heavy thinking, but I wonder what’s on the other stations. My fingers instinctively hit the button for the only other accessible old- ies station, from Pueblo, Colorado, fifty-seven miles to the south. Recep- tion of Pueblo’s station wasn’t always very good at my house in the Springs, but sometimes I could pick it up while perched on the mountainside where the Academy was located. That night, in fact, I was in luck. The music came in softly but clearly: “Yester-Me, Yester-You, Yesterday.” Stevie Wonder. That’s odd, I thought. The same more-than-twenty-year-old song play- ing at the same time on two different stations in two different towns. -

Top Wedding Song Choices

Top Wedding Song Choices A Groovy Kind of Love Phil Collins A Moment Like This Kelly Clarkson A While New World Peabo Bryson/Regina Belle After All Peter Cetera All About Lovin’ You Bon Jovi All My Life K-CI and JO JO All the Way Frank Sinatra Always Atlantic Starr Always Bon Jovi Amazed Lonestar Angel in My Eyes John Michael Montgomery Angel of Mine Monica At Last Etta James Beautiful in my Eyes Joshua Kadison Because You Loved Me Celine Dion Best Part of Me Joe Wodarek Breathe Faith Hill By Your Side Sade Can You Feel The Love Elton John Can’t Help Falling In Love Elvis Can’t Take My Eyes Off of You Frankie Valli Color My World Chicago Come What May McGregor/Kidman Could I Have This Dance Anne Murray Crazy for You Madonna Don’t Know Much Linda Rondstadt/Aaron Neville Dreaming of You Selena Endless Love Diana Ross/Lionel Ritchie Everything I Do Bryan Adams Everytime I Close My Eyes Babyface Faithfully Journey Feels Like Home Chantal Kreviazuk First Time Ever I Saw Your Face Roberta Flack Fly Me to the Moon Frank Sinatra Flying Without Wings Ruben Studdard For the First Time Kenny Loggins For You Kenny Lattimore For You I Will Monica Forever Beach Boys Forever and Ever Randy Travis Forever and Always Shania Twain Forever In Love Kenny G Forever More James Ingram Forever My Lady Jodeci Forever’s as Far as I’ll Go Alabama From Here to Eternity Michael Patterson From Now On Regina Belle From This Moment Shania Twain Give Me Forever John Tesh/James Ingram Giving You the Rest of My Life Bob Carlisle Glory of Love Peter Cetera God Must Have -

Appendix B: Transcript Bravely Default

Appendix B: Transcript Bravely Default Applied JGRL usage tagging styles: Gender-conforming Gender-contradicting Gender-neutral (used to tag text which is easily confusable as JGRL) Gender-ambiguous Notes regarding preceding text line Finally, instances of above tagging styles applied to TT indicate points of interest concerning translation. One additional tagging style is specifically used for TT tagging: Alternate translations of ‘you’ 『ブレイブリーデフォルトフォーザ・シークウェル』 [BUREIBURII DEFORUTO FOOZA・ SHIIKUWERU]— —“BRAVELY DEFAULT” 1. 『オープニングムービー』 [Oopuningu Muubii] OPENING CINEMATICS AIRY anata, ii me wo shiteru wa ne! nan tte iu ka. sekininkan ga tsuyo-sou de, ichi-do kimeta koto wa kanarazu yaritoosu! tte kanji da wa. sonna anata ni zehi mite-moraitai mono ga aru no yo. ii? zettai ni me wo sorashicha DAME yo. saigo made yaritokete ne. sore ja, saki ni itteru wa. Oh, hello. I see fire in those eyes! How do I put it? They’ve a strong sense of duty. Like whatever you start, you’ll always see through, no matter what! If you’ll permit me, there’s something I’d very much like to show you. But… First, I just need to hear it from you. Say that you’ll stay. Till the very end. With that done. Let’s get you on your way! ACOLYTES KURISUTARU no kagayaki ga masumasu yowatte-orimasu. nanika no yochou de wa nai deshou ka. hayaku dou ni ka shimasen to. The crystal’s glow wanes by the hour. It’s fading light augurs a greater darkness. Something must be done! AGNÈS wakatteimasu. Leave all to me. AGNÈS~TO PLAYER watashi no namae wa, ANIESU OBURIIJU. -

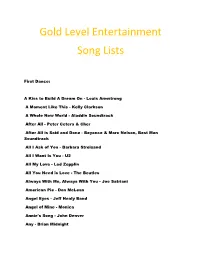

Gold Level Entertainment Song Lists

Gold Level Entertainment Song Lists First Dance: A Kiss to Build A Dream On - Louis Armstrong A Moment Like This - Kelly Clarkson A Whole New World - Aladdin Soundtrack After All - Peter Cetera & Cher After All is Said and Done - Beyonce & Marc Nelson, Best Man Soundtrack All I Ask of You - Barbara Streisand All I Want Is You - U2 All My Love - Led Zepplin All You Need is Love - The Beatles Always With Me, Always With You - Joe Satriani American Pie - Don McLean Angel Eyes - Jeff Healy Band Angel of Mine - Monica Annie's Song - John Denver Any - Brian Midnight As Long as I'm Rocking With You - John Conlee At Last - Celine Dion At Last - Etta James At My Most Beautiful - R.E.M. At Your Best - Aaliyah Battle Hymn of Love - Kathy Mattea Beautiful - Gordon Lightfoot Beautiful As U - All 4 One Beautiful Day - U2 Because I Love You - Stevie B Because You Loved me - Celine Dion Believe - Lenny Kravitz Best Day - George Strait Best In Me - Blue Better Days Ahead - Norman Brown Bitter Sweet Symphony - Verve Blackbird - The Beatles Breathe - Faith Hill Brown Eyes - Destiny's Child But I Do Love You - Leann Rimes Butterfly Kisses - Bob Carlisle By My Side - Ben Harper By Your Side - Sade Can You Feel the Love - Elton John Can't Get Enough of Your Love, Babe - Barry White Can't Help Falling in Love - Elvis Presley Can't Stop Loving You - Phil Collins Can't Take My Eyes Off of You - Frankie Valli Chapel of Love - Dixie Cups China Roses - Enya Close Your Eyes Forever - Ozzy Osbourne & Lita Ford Closer - Better than Ezra Color My World - Chicago Colour -

Escaping Eden

Escaping Eden Chapter 1 I wake up screaming. Where am I? What’s going on? Why do I feel so cold? It’s dark. I look around, blinking sleep from my eyes. I notice a window somewhere in the back of the room. It’s open and moonlight shines through, casting a square beam of light across the floor. A breeze drifts in, and white curtains float like pale ghosts in the darkness. In the narrow light of the moon, I see that the carpet is burgundy. I also see the outlines of furniture. My head vaguely aching, I look at the shadows scattered messily across the room. I feel like sweeping them up to make room for light. I shake off the urge. Stop being delusional. There’s a funny smell in the air, like a mixture of old home mustiness and laboratory sterilization. I realize that I’m lying on the floor. Why am I not on the bed? The last thing I remember is pain. Maybe that’s why I woke up screaming. The pain was intense. The pain was… cold. I decide to swallow my fear. It tastes terrible. I stand up and my neck aches. As I rub my hand across it, my bones crack like I haven’t moved in a long time. I whisper to myself. “As Grandpa always said…” My train of thought rolls off into the distance. Where was I going with this? Who is “Grandpa”? I put my hand on my sweaty forehead. I must be tired. I look for a light switch by approaching the walls and groping around. -

Charms, Charmers and Charming Российский Государственный Гуманитарный Университет Российско-Французский Центр Исторической Антропологии Им

Charms, Charmers and Charming Российский государственный гуманитарный университет Российско-французский центр исторической антропологии им. Марка Блока Институт языкознания РАН Институт славяноведения РАН Заговорные тексты в структурном и сравнительном освещении Материалы конференции Комиссии по вербальной магии Международного общества по изучению фольклорных нарративов 27–29 октября 2011 года Москва Москва 2011 Russian State University for the Humanities Marc Bloch Russian-French Center for Historical Anthropology Institute of Linguistics, Russian Academy of Sciences Institute of Slavic Studies, Russian Academy of Sciences Oral Charms in Structural and Comparative Light Proceedings of the Conference of the International Society for Folk Narrative Research’s (ISFNR) Committee on Charms, Charmers and Charming 27–29th October 2011 Moscow Moscow 2011 УДК 398 ББК 82.3(0) О 68 Publication was supported by The Russian Foundation for Basic Research (№ 11-06-06095г) Oral Charms in Structural and Comparative Light. Proceedings of the Con- ference of the International Society for Folk Narrative Research’s (ISFNR) Committee on Charms, Charmers and Charming. 27–29th October 2011, Mos- cow / Editors: Tatyana A. Mikhailova, Jonathan Roper, Andrey L. Toporkov, Dmitry S. Nikolayev. – Moscow: PROBEL-2000, 2011. – 222 p. (Charms, Charmers and Charming.) ISBN 978-5-98604-276-3 The Conference is supported by the Program of Fundamental Research of the De- partment of History and Philology of the Russian Academy of Sciences ‘Text in Inter- action with Social-Cultural Environment: Levels of Historic-Literary and Linguistic Interpretation’. Заговорные тексты в структурном и сравнительном освещении. Мате- риалы конференции Комиссии по вербальной магии Международного об- щества по изучению фольклорных нарративов. 27–29 октября 2011 года, Москва / Редколлегия: Т.А. -

Starstone, a Jewel Rider Fanfic by Stormdance

Author's note from 2012: This story was written 1995 or thereabouts. I present it here unaltered, for the nostalgic enjoyment of my past fans who requested I post it. Please remember, if this reads like a high-schooler with her first Mary Sue, well, that's exactly what I was! Scroll to the end for a special bonus look at the Trina sequel stories that never saw the light of day! Since then Jewel Riders has changed hands a few times; I think Digiview owns the rights at the moment so please pretend I updated the disclaimers. My old email no longer works; I'm now [email protected] if for some reason you want to email me. Starstone, a Jewel Rider fanfic by Stormdance Disclaimer: Everyone you’ve seen on TV belongs to Amazin Entertainment and/or Robert Mandell as far as I know. Trina, Silverwind, and anyone else are mine. I’m not making any money off this. Author’s note: Hiya all, I’m Stormdance and I’m to blame for the story you’re here to read. There *will* eventually be a Jewel Riders homepage connected to the story, but that’ll be in the future when I can get a computer literate family member to help me make it. While I didn’t knowingly contradict anything in the show, there are episodes I haven’t seen so I’m sure I slipped up somewhere. A lot of this is me writing the way things *might* have happened, especially Fallon and Tamara’s pasts and details about magic and Avalon.