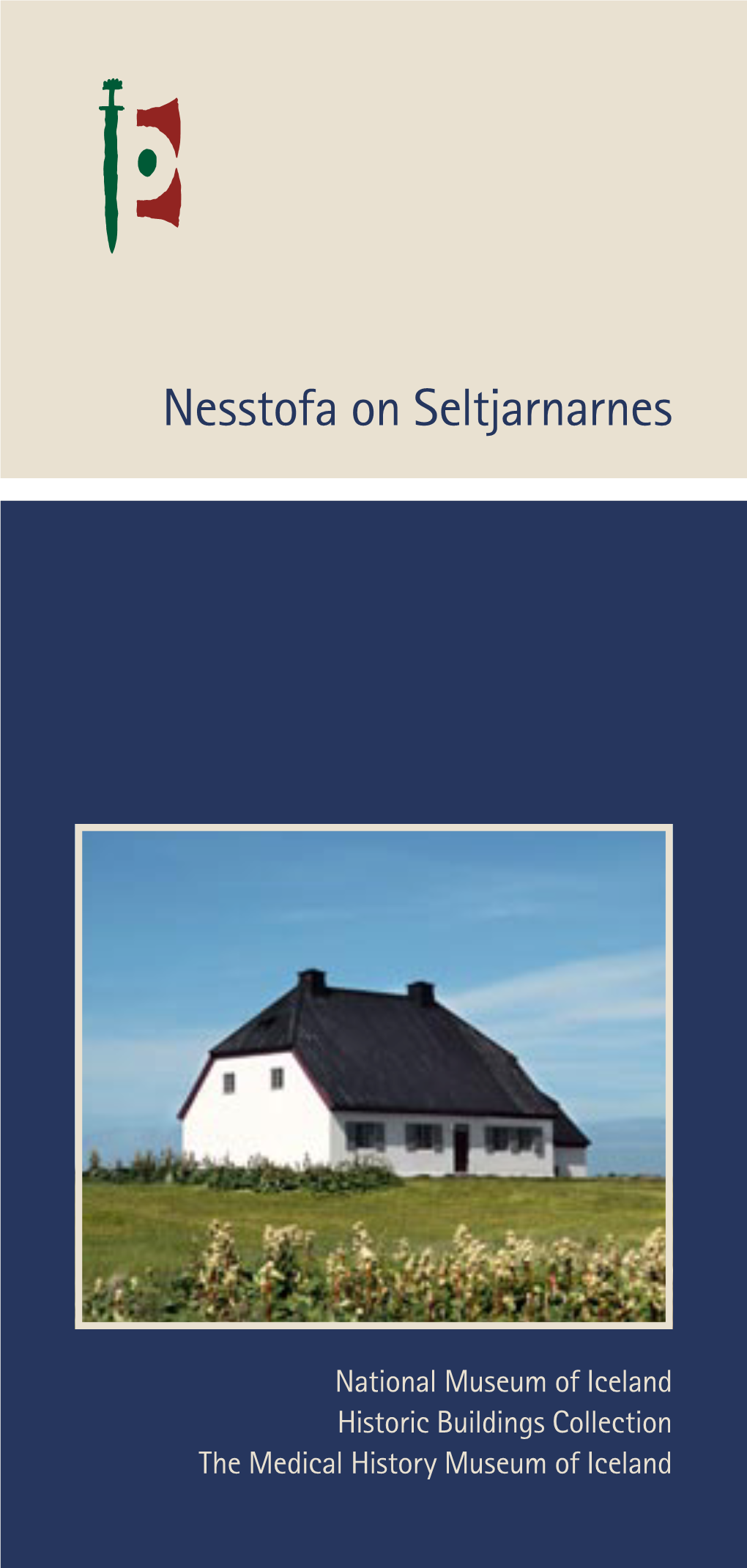

Nesstofa on Seltjarnarnes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inger Kjær Jansen KASTRUPGARD Fra Hovedgård Til Kultursted

Inger Kjær Jansen KASTRUPGARD Fra hovedgård til kultursted Tårnby Kommunes Lokalhistoriske Samling 1992 KASTRUPGÅRD Fra hovedgård til kultursted Inger Kjær Jansen Inger Kjær Jansen . 0 KASTRUPGARD Fra hovedgård til kultursted Tårnby Kommunes Lokalhistoriske Samling 1992 "Kastrupgård. Fra Hovedgård til kultursted". Udgivet af Tårnby Kommunes Lokalhistoriske Samling. Sats og tryk: lønsson og Nomi. Oplag: 2000 eksemplarer. Copyright: Tårnby Kommunebiblioteker. ISBN 87-891893-07-0 Kastrupgård 1992. FORSIDE. Foto: Dirch lansen Kastrupgård, 1992. BAGSIDE. Foto: Dirch lansen. 4 FORORD KASTRUPGÅRD er et kulturhistorisk klenodie, som vi kan glæde os over, at en fremsynet kommunalbestyrelse i 50' eme havde såvel mod som klarsyn til at overtage og dermed bevare for eftertiden. Den smukke, gamle gård er i dag en velfungerende ramme om en lang række spræl-levende kulturelle aktiviteter. Der er kunstmuseum, der er bibliotek -med hele den mangfoldighed af muligheder; som den slags i øvrigt velkendte offentlige institutioner kan byde på : udstillinger, udlån, arrangementer, teater, hobbyinstruktioner, koncerter, kaffe og kageri cafeen, foredrag, rundvisninger, mødeaktiviteter og meget andet. I disse dage går et længe næret ønske i opfyldelse : Tårnby kommunes lokalhistoriske Samling, som har til huse på Hovedbiblioteket på Kamillevej, udvides med en permanent udstilling i kælderen på Kastrupgård. Her kan Tårnby kommunes borgere for fremtiden i Kastrup gårdsamlingens åbningstid stifte bekendtskab med mange af de spændende lokalhistoriske rariteter, der gennem årene er indgået i Lokalhistorisk Samling, men som af pladshensyn har været forvist til magasinet. Det nye "museum" hører naturligt til på Kastrupgårdsamlingens øvrige udstillings- virksomhed. I en årrække har lederen af Lokalhistorisk Samling, Inger Kjær Jansen, beskæftiget sig med Kastrupgårds spændende historie. -

Ledreborg Allé 2, Ledreborg, Lejre, Fredningsbeskrivelse.Pdf

FREDNINGSVÆRDI ER LEDREBORG LEJRE KOMMUNE 2 Besigtigelsesdato: 17.11.2010 Besigtiget af: Simon Harboe Journalnummer: 2011-7.82.07/350-0001 Kommune: Lejre Kommune Adresse: Ledreborg Allé 2, 4320 Lejre Betegnelse: Ledreborg Fredningsår: 1918. Udv. 1978 og 1986 Omfang: "Hovedbygningen (de midterste ni fag fra ca. 1660, ombygget og udvidet 1741-45 af Johan Cornelius Krieger) med sidefløje (de svungne pavilloner 1748-50 af Lauritz de Thurah), øst- og vestfløjene (1742-46 af Johan Cornelius Krieger) og portbygning (antagelig 1799), gitteret på gårdspladsen, de to bassiner, de seks obelisker og kældernedgangen med tilhørende gitter og flisebelægning, hegnsmure øst og vest for hovedbygningen, de to sandstensfigurer i haven (muligvis af Johann Friedrich Hännel) og "Amalienborgporten" ved den østlige indkørsel, "Det peripatetiske Akademi" (1755-62), statuerne af Knud den Store og Dronning Margrethe (begge af S.C. Stanley), to buster og syv obelisker i Dyrehaven og to buster i den sydvendte slotshave. BYGNINGSBESKRIVELSE Herregården Ledreborg ligger i et kuperet, skovfyldt terræn vest for Roskilde. Bygningsanlægget er orienteret omkring en nord- sydgående akse, hvis centrum er hovedbygningen, som ligger placeret på kanten af Kornerup ådal. Nord for hovedbygningen findes den centrale gårdsplads, hvorom de fredede bygninger ligger symmetrisk placeret, mens slotshaven ligger i dalsænkningen mod syd. Fælles for de fredede bygninger er, at de alle står på kampestenssokler, er grundmurede, har opsprossede vinduer, tegltage og er pudsede og kalkede i den samme okkergule farve. Ankomsten til herregårdsanlægget finder sted gennem en monumental allé, som begynder 7,3 kilometer længere mod øst, umiddelbart vest for Roskilde, og som fortsætter forbi hovedbygningen for at ende i en rundgang omkring den Holsteinske familiegravplads. -

Fredede Bygninger

Fredede Bygninger September 2021 SLOTS- OG KULTURSTYRELSEN Fredninger i Assens Kommune Alléen 5. Løgismose. Hovedbygningen (nordøstre fløj beg. af 1500-tallet; nordvestre fløj 1575, ombygget 1631 og 1644; trappetårn og sydvestre fløj 1883). Fredet 1918.* Billeskovvej 9. Billeskov. Hovedbygningen (1796) med det i haven liggende voldsted (1577). Fredet 1932. Brahesborgvej 29. Toftlund. Det fritliggende stuehus (1852-55, ombygget sidst i 1800-tallet), den fritliggende bindingsværksbygning (1700-tallet), den brostensbelagte gårdsplads og kastaniealléen ved indkørslen. Fredet 1996.* Delvis ophævet 2016 Brydegaardsvej 10. Brydegård. Stuehuset, stenhuset (ca. 1800), portbygningen og de to udhusbygninger (ca. 1890) samt smedien (ca. 1850). F. 1992. Byvejen 11. Tjenergården. Det firelængede anlæg bestående af et fritliggende stuehus (1821), tre sammenbyggede stald- og ladebygninger og hesteomgangsbygningen på østlængen (1930) samt brolægningen på gårdspladsen. F. 1991.* Damgade 1. Damgade 1. De to bindingsværkshuse mod Ladegårdsgade (tidl. Ladegårdsgade 2 og 4). Fredet 1954.* Dreslettevej 5. Dreslettevej 5. Det firelængede gårdanlæg (1795, stuehuset forlænget 1847), tilbygningen på vestlængen (1910) og den brolagte gårdsplads. F. 1990. Ege Allé 5. Kobbelhuset. Det tidligere porthus. Fredet 1973.* Erholmvej 25. Erholm. Hovedbygningen og de to sammenbyggede fløje om gårdpladsen (1851-54 af J.D. Herholdt). Fredet 1964.* Fåborgvej 108. Fåborgvej 108. Det trelængede bygningsanlæg (1780-90) i bindingsværk og stråtag bestående af det tifags fritliggende stuehus og de to symmetrisk beliggende udlænger, begge i fem fag, den ene med udskud og den anden forbundet med stuehuset ved en bindingsværksmur forsynet med en revledør - tillige med den brostensbelagte gårdsplads indrammet af bebyggelsen. F. 1994. Helnæs Byvej 3. Bogården. Den firelængede gård (stuehuset 1787, udlængerne 1880'erne). -

Amager På Vrangen Natur- Og Kulturformidling, 1

Amager på vrangen Natur- og kulturformidling, 1. semester Eksamenstermin januar 2015 Carl Gustav Hansen • nat1401 Cathrine Kongslev • nat1409 Mai Haugaard Westhoff • nat1423 Michaela Gorosch Kviat • nat1426 Pernille Ungermann • nat1417 Underviser/vejleder • Laura Lundager Jensen Antal sider/antal anslag (incl. mellemrum) 53/89.754 Amager på vrangen • Natur- og kulturformidling, 1. semester • Eksamenstermin januar 2015 Underviser/vejleder • Laura Lundager Jensen • Professionshøjskolen Metropol Indhold 1. Indledning. 1 2. Problemformulering . 2 3. Metode. 3 4. Målgruppe. 4 5. Historisk baggrund . 5 6. Afgrænsning. 7 7. Produktbeskrivelse . 10 7.1 Teknologiske hjælpemidler . 10 7.2 Eventuelle samarbejdspartnere . 11 8. Produktet . .12 8.1 Linje 1. 12 Bryggen – Det industrielle er blevet forvandlet til et moderne område . 12 VM Bjerget og VM Husene – Her er moderne arkitektur med kolonihavestemning . .16 8.2 Linje 2 . 19 Vor Frelser Kirkegård, Slavekirkegården og Retterstedet – Her regerede manden med leen . 19 Kastrup Fort – En blodig myte blev til i fortidens krigshistorie. .23 Kastrup Værk – En ambitiøs mand opbygger øens fundament . 25 9. Teori . .28 9.1 Kultur . 28 9.1.1 Mikrohistorie . 28 9.1.2 Kildekritik . 29 9.1.3 Historiebevidsthed . 29 9.2 Turisme. 31 9.2.1 Decentrering. .32 9.2.2 Recentrering. .32 9.3 Formidling . 33 10. Analyse. 36 10.1 Kulturteoretisk analyse . 36 10.1.1 Mikro- overfor makrohistorie. 36 10.1.2 Historiebevidsthed. 36 10.1.3 Kildekritik . 37 10.2 Turismeteoretisk analyse . 38 10.3 Formidlingsteoretisk analyse . .40 10.3.1 Theme. .41 10.3.2 Organized. 41 10.3.3 Relevant. 41 10.3.4 Enjoyable . 42 11. Diskussion . .42 12. -

Parker I Tårnby De Grønne Områder

TÅRNBY KOMMUNES LOKALHISTORISKE TIDSSKRIFT JULI/AUGUST 2015 PARKER I TÅRNBY De grønne områder NUMMER 4 / 2015 FORSIDE: Kastrup Strandpark med krogede træer. Kunstneren Søren Georg Nielsen udførte i 1981 skulpturen, som nu er opstillet i den fredede park. Fotograf: Helle Stokkilde. Foto: Tårnby Stads- og Lokalarkiv kildER Arkivalier fra Teknisk Forvaltning: Æ5100 Planafdelingen Æ5104 Vej, Park og Forsyning Travbaneparken. Tårnby Kommunes Informationsudstilling august 1976. (L71.966) Diverse udklip fra Tårnby Stads- og Lokalarkiv http://pictures.science.ku.dk/haver COPYRIGHT Ophavsretten på billederne og illustrationerne tilhører Tårnby Stads- og Lokalarkiv, en anden in- stitution eller en professionel fotograf. Fotografierne må ikke bruges i andre sammenhænge uden tilladelse. Har du brug for et billede eller en illustration, kan du henvende dig til Tårnby Stads- og Lokalarkiv. Læs mere på https://taarnbybib.dk/page/copyright © Tårnby Stads- og Lokalarkiv 2015 For enkelte billeder har det været umuligt at finde frem til den retmæssige ophavsretsindehaver. Dersom Tårnby Stads- og Lokalarkiv krænker ophavsretten, er det ufrivilligt og utilsigtet. Såfremt du mener, der er materiale, der tilhører dig, bedes du derfor kontakte [email protected] HVIS DU VIL VIDE MERE: Tjek arkivets del af bibliotekets hjemmeside på https://taarnbybib.dk/ Tidsskriftet Glemmer Du er udgivet af: © Tårnby Kommunebiblioteker, Stads- og Lokalarkivet ISSN 1397-5412 Tekst: Peter Damgaard Redaktion: Lone Palm Larsen Layout: Anne Petersen GLEMMER PARKER I TÅRNBY DU De grønne områder | De grønne områder udgør næsten halvdelen af Tårnby Kommunes areal. Og NUMMER så er Saltholm ikke engang medregnet. I Tårnby er der marker og parker tillige med fine kyststrækninger mod øst og vest og ikke at forglemme den store Naturpark Amager. -

CV Luise Skak-Nielsen Og John Erichsen

CV John Erichsen februar 2019 Født i København 30.12.1942 Student, nysproglig Sorø Akademi 1962 Marinen, Danmark og Tyskland 1962-64 Cand.mag. historie og kunsthistorie, Aarhus og Københavns Universiteter 1972 Studieophold Rom og Frankrig: Dronning Ingrids Romerske Fond og den italienske stats stipendium (barokkens byplan og arkitektur) 1972-73 Studieophold Holland: Tildelt hæderslegatet ’Brygger Carl Jacobsens Legat til en museumsmand’ (renæssancens og barokkens byplan, fortifikation og arkitektur) 1974 Embeder og ansættelser: Museumsinspektør Københavns Bymuseum 1973-80 Museumschef Københavns Bymuseum 1980-86 Overinspektør og leder af Nationalmuseets 3. Afdeling (Dansk Folkemuseum) 1986-89 Museumschef Nationalmuseets Afdeling for Nyere Tid: Danske samlinger fra 1660 til nutiden (chef for Dansk Folkemuseum, Frilandsmuseet og Frihedsmuseet) 1989-97 Medlem af Nationalmuseets direktion 1987-97 Medlem af Det særlige Bygningssyn 1986-97 (næstformand) Selvstændig virksomhed (HISTORISMUS) fra 1997 Konsulent Norsk Folkemuseum 1997-2001, konsulent Reventlow-Museet Pederstrup 2000-2009. Fagkonsulent vedr. herregårde, slotte og præstegårde, Trap Danmarks 6. udgave 2015- 1 Akademiske hverv: Undervisningsassistent Institut for Kunsthistorie, Københavns Universitet 1978-79 Censor i kunsthistorie (barokkens arkitektur og havekunst) Københavns og Aarhus Universiteter 1998-2006 Bedømmelsesudvalg vedr. Kirsten Lindbergs doktorafhandling ’Sirenernes Stad – København. By- og bygningshistorie før 1728’ 1995-96, 1. opponent Københavns Universitet 1996 Vejleder ved Lars Roedes doktorgradsstudium ’Byen bytter byggeskik - Christiania 1624- 1814’, Arkitekthøgskolen i Oslo 1997-2001 Bedømmelseskomité for Einar Sørensens doktorafhandling: ’Adelens norske hus – Byggevirksomheten på herregårdene i sørøstre Norge 1500-1660’, Universitetet i Oslo 2003, 2. opponent Bedømmelseskomité for Lars Jacob Hvinden-Haugs doktorafhandling: ’Den eldre barokken i Norge – bygningenes former og rommenes fordeling 1660-1733.’ Arkitekthøgskolen i Oslo 2007-08, 1. -

Planforhold, Arkitektur & Landskab, Kultur Og Rekreative Forhold

Planforhold, arkitektur & landskab, kultur og rekreative forhold -Fagnotat, juni 2011 Kapacitetsudvidelse på Øresundsbanen Kapacitetsudvidelse på Banedanmark Øresundsbanen Anlægsudvikling Juni 2011 Amerika Plads 15 2100 København Ø ISBN 978-87-7126-026-7 www.banedanmark.dk Undersøgelse af Kapacitetsudvidelse på Øresudnsbanen er samfinansieret af EU via Det transeuropæiske transportnet (TEN-T). Forfatteren har det fulde ansvar for denne publikation. Den Europæiske Union fralægger sig ethvert ansvar for brugen af oplysningerne i publikationen. Kapacitetsudvidelse på Øresundsbanen Indhold Side 1 Forord 6 2 Indledning 7 3 Ikke teknisk resumé 9 3.1 Planforhold 9 3.2 Arkitektur og Landskab 9 3.3 Kulturhistorie 10 3.4 Rekreative forhold 11 4 Planforhold 12 4.1 Indledning 12 4.2 Metode 12 4.3 Planforhold 13 4.3.1 Internationale beskyttelsesforhold 13 4.3.2 Nationale beskyttelsesforhold 13 4.3.3 Bygge og beskyttelseslinjer 14 4.3.4 Kommunal planlægning 15 4.4 Sammenfatning og sammenligning af løsninger 18 5 Arkitektur og landskab 21 5.1 Indledning 21 5.2 Lovgrundlag 21 5.3 Metode 21 5.3.1 Forundersøgelse 21 5.3.2 Besigtigelse 22 5.3.3 Beskrivelse af eksisterende by- og landskabsområder 22 5.3.4 Afværgeforanstaltninger 22 5.4 Eksisterende By- og landskabsområder 22 5.4.1 Dominerende træk 23 5.4.2 Bebyggelsesstrukturer 24 5.4.3 Grønne strukturer 25 5.4.4 Enkeltstående elementer 26 5.5 Konsekvenser og afværgeforanstaltninger i anlægsfasen 27 5.5.1 Grundløsning. Sporsluse 27 5.5.2 Alternativ 1. Fly-over over motorvej 27 5.5.3 Alternativ 2. Fly-over over bane 28 5.5.4 Tilvalg 1 Perroner Kastrup Station 28 5.5.5 Tilvalg 2 Overhalingsspor Ørestad Station 28 5.6 Konsekvenser og afværgeforanstaltninger i driftsfasen 29 5.6.1 Grundløsning sporsluse 29 5.6.2 Alternativ 1. -

Fra Københavns Nordvestegn De Store Skove

Ture i Københavns omegn Kulturhistorie • Natur • Landskab 4 Indholdsfortegnelse Tag ud og oplev Københavns omegn 7 Københavns omegn 8 Sådan er guiden bygget op 9 Fra Øresunds kyst 10 Udvalgte seværdigheder 12 Vandretur Høje Sandbjerg – Rygård Overdrev 14 Vandretur Vedbæks landsteder 16 Vandretur Vaserne – Frederikslund Skov ved Holte 18 Cykeltur Vedbæk – Grisestien – Bøllemosen 20 Cykeltur Skodsborg – Holte 22 Fra Københavns nordegn 24 Udvalgte seværdigheder 26 Vandretur Ved Frederiksdal Slot 28 Vandretur Gentofte Sø – Brobæk Mose 30 Cykeltur Københavns Befæstning, Lyngby-Klampenborg 32 Cykeltur Lyngby Åmose – Frederiksdal 34 Cykeltur Rundt om Bagsværd Sø og Lyngby Sø 36 Cykeltur Langs Mølleåen fra Sorgenfri til Skodsborg 38 Cykeltur Københavns Befæstning, Lyngby-Husum 40 Fra Københavns nordvestegn 42 Udvalgte seværdigheder 44 Vandretur Fugle ved Præstesø i Værløse 46 Vandretur Frederiksdal Skov 48 Vandretur Kirke Værløse – Ryget – Farum Sø 50 Cykeltur Værløse – Søndersø – Sækken – Farum 52 Cykeltur Skovbrynet – Ballerup 54 5 Fra Københavns vestegn 56 Udvalgte seværdigheder 58 Vandretur Ved Edelgave Gods 60 Vandretur Herstedøster og Herstedvester 62 Vandretur Risby – Porsemosen – Vestskoven 64 Vandretur Ledøje Landsby 66 Cykeltur Ballerup – Store Vejleå – Albertslund 68 Cykeltur Ballerup – Ledøje – Veksø 70 Cykeltur Vestegnens gravhøje 72 Fra Amager og Saltholm 74 Udvalgte seværdigheder 76 Vandretur Rundt om Kongelunden 78 Vandretur Dragør – Store Magleby 80 Cykeltur Sydamager 82 Cykeltur Avedøre – Vestamager 84 Cykeltur Amager Strandpark – Dragør 86 Museer og lokalarkiver 88 Register over stednavne og seværdigheder 90 Udarbejdet af: Københavns Amt Teknisk Forvaltning Stationsparken 27 2600 Glostrup Forsidefoto: Københavns Amt. Gadekæret i Sengeløse. Foto: John Jedbo, Ole Malling, Bo Hansen, Cappelen, Tøjhusmuseet og Københavns Amt Kort: © Kort og Matrikelstyrelsen Tryk: Paritas Grafi k ISBN: 87-7951-022-1 Oktober 2005 6 7 Tag ud og oplev Københavns omegn Der er meget at opleve i Københavns Amt. -

Dansk Luftfart På Museum Der Er Tændt for Valget Hvis Man Interesserer Sig Sterende Flyselskab

TÅRNBYTÅRNBY BLADETBLADETAUGUST 2017 NR. 8 - AUGUST 2017 • 25. ÅRGANG • WWW.TAARNBYBLADET.DK Blå toner i blå time Sneglen er et fantastisk sted, ikke mindst om som- meren på det tidspunkt, hvor solen går ned og al dagens aktivitet er stilnet af. Oplev stedets stemning og atmosfære forstærket og tilført noget ekstra med en lille times koncert. Ved koncerterne spiller de to musikere og komponi- ster, Mikael Tosti og Henrik Jespersen, der tidligere har arbejdet med kombinatio- nen udendørs rum og musik. Henrik Jespersen spiller fle- re blæseinstrumenter, der både forstærkes og tilføres effekter elektronisk - og Mikael Tosti spiller violin og keyboards kombineret med elektronik. Hertil kommer enkelte musikalske gæster, som medvirker de enkelte aftener. Koncerterne er ar- rangeret af Mikael Tosti i samarbejde med Tårnby Kommune. Foto: Kurt Pedersen. Amager Fotoklub Dansk luftfart på museum Der er tændt for valget Hvis man interesserer sig sterende flyselskab. maer over en tidsperiode fra De politiske partier delta- Også med- for fly og for SAS-relaterede Der er flymodeller i en- DDL’s start i 1918 og op gen- ger på markeder og møder mennesker, fly-rariteter i særdeles- hver tænkelig størrelse, og nem årene med SAS’ opstart med bud på deres kommu- der er ble- hed, så er det bare med at en gammel telefoncentral, i 1946 og frem til vor tid. En nalpolitik vet alene komme afsted en tur ud i uniformer, et cockpit, ja selv stor del af de viste genstande i høj alder, Af Terkel Spangsbo, lufthavnen. en biograf bygget op som en er samlet eller doneret af behøver en redaktør på Tårnby Bladet Her åbnede SAS Flyverhisto- DC-9’er, er der blevet plads gamle luftfartsansatte. -

Amagerbanen På Skinner

Amagerbanen på skinner Udflugtstog 1972, Foto: Allan Meyer Allan Meyer Udstillingscenter Plyssen 2016 Indhold Forord .................................................................... 2 Planer..................................................................... 3 Anlæg og drift ........................................................ 4 Strækning og stationer ........................................... 4 Amagerbro - Øresundsvej .................................. 4 Amagerbro station .......................................... 4 Godsstationen ................................................ 5 Øresundsvej ................................................... 5 Engvej trb. ...................................................... 5 Syrevej - Kastrup ................................................ 7 Syrevej ............................................................ 7 Saltværksvej ................................................... 8 Kastrup ........................................................... 8 Lufthavnen trb. .............................................. 10 Tømmerup – Dragør ........................................ 10 Tømmerup .................................................... 10 Store Magleby .............................................. 12 Dragør .......................................................... 13 Postbefordring ..................................................... 15 Rullende materiel ................................................. 16 Damplokomotiver ............................................. 16 Motormateriel .................................................. -

AMAGER BREVE Postkort Og Breve Fra En Samler

TÅRNBY KOMMUNES LOKALHISTORISKE TIDSSKRIFT JANUAR / FEBRUAR 2019 AMAGER BREVE Postkort og breve fra en samler NUMMER 1 / 2019 Forside: Viberupgård. Foto: Tårnby Stads- og Lokalarkiv, B8008 Tømmerup Kommuneskole. Foto: Tårnby Stads- og Lokalarkiv, B8012 Du kan se forsidens fotografier på arkiv.dk – skriv nummeret i søgefeltet. Se hvordan du søger på: https://taarnbybib.dk/sol/betjen-dig-selv-i- lokalhistorien/soeg-i-arkivets-materiale-paa-arkivdk Copyright: Ophavsretten på billederne og illustrationerne tilhører Tårnby Stads- og Lokalarkiv, en anden in- stitution eller en professionel fotograf. Fotografierne må ikke bruges i andre sammenhænge uden tilladelse. Har du brug for et billede eller en illustration, kan du henvende dig til Tårnby Stads- og Lokalarkiv. For enkelte billeder har det været umuligt at finde frem til den retmæssige ophavsretsindehaver. Dersom Tårnby Stads- og Lokalarkiv krænker ophavsretten, er det ufrivilligt og utilsigtet. Såfremt du mener, der er materiale, der tilhører dig, bedes du derfor kontakte [email protected] Kilder: Breve og postkort fra Amager fra privatsamler – indhold er tilrettet nutidig skrive- og stavemåder. Arkivet ved Dansk Centralbibliotek for Sydslesvig A1019 Personarkiv: Mylord-Møller-familien [arkiv.dk] danskeherregaarde.dk finnholbek.dk https://www.kbharkiv.dk/sog-i-arkivet/sog-i-indtastede-kilder#/ Koefoed, Michael: Skatterne i Danmark 1870—1900. En statistisk Undersøgelse. I: Nationaløko- nomisk Tidsskrift, Bind 3. række 10, 1902. HVIS DU VIL VIDE MERE: Tjek arkivets del af bibliotekets hjemmeside på www.taarnbybib.dk ISSN 1397-5412 © Tårnby Stads- og Lokalarkiv 2019 Tidsskriftet GLEMMER DU Tekst og redaktion: Lone Palm Larsen Layout: Anne Petersen Oversættelse af breve: Eyvind Christensen GLEMMER DU AMAGER BREVE Postkort og breve fra en samler | NUMMER 1 Der er skatte at finde mange steder. -

På Cykeltur Amager Strandpark – Dragør

Det nye søbad ved Kastrup Strand. Foto: Københavns Amt 24 På cykeltur Amager Strandpark – Dragør På cykelturen fra den nye Amager Strandpark til Dragør kan du langs hele kysten opleve mange af de aktiviteter, der er knyttet til en storbys udkant. På turen kan du se de store fragtskibe sejle igennem Øresund og i himmelrummet over gør den ene fl yver efter den anden klar til landing. Du kommer forbi en nyanlagt bred badestrand og det nye Kastrup Søbad. Turen slutter ved Dragør med de charmerende gamle gulkalkede huse og smalle brostensbelagte gader. A Amager Strandpark er indviet i august 2005. Ud for den gam- E Københavns Lufthavn er landets største arbejdsplads med ca. le strand er der nu en helt ny 2 km lang ø med brede strande og ba- 22.000 ansatte. 19 millioner mennesker passerer årligt gennem debroer. Der er udlagt store arealer som naturområder. I lagunen lufthavnen og hvert andet minut letter eller lander et fl y. I 2003 mellem øen og den gamle strand er der indrettet soppestrande til blev vejen øst om lufthavnen åbnet for trafi k. Er vindforholdene de børn og en 1.000 meter svømme- og robane. Inde på land er de sto- rigtige fl yver de store maskiner tæt hen over hovedet på én. re parker – 5’øren og 10’øren – bevaret. F Øresundsbroen gjorde ved åbningen i 2000 Danmark og Sve- B Kastrup Søbad genåbnede i 2004 efter den gamle badeanstalt rige landfast. Tunnelen fra Danmark forener sig med broen på den fra 1912 måtte vige for Øresundsbroen. Søbadet er forbundet med kunstige ø, Peberholm.