Giovanni Segantini Light, Colour, Distance and Infinity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alberto Giacometti: a Biography Sylvie Felber

Alberto Giacometti: A Biography Sylvie Felber Alberto Giacometti is born on October 10, 1901, in the village of Borgonovo near Stampa, in the valley of Bregaglia, Switzerland. He is the eldest of four children in a family with an artistic background. His mother, Annetta Stampa, comes from a local landed family, and his father, Giovanni Giacometti, is one of the leading exponents of Swiss Post-Impressionist painting. The well-known Swiss painter Cuno Amiet becomes his godfather. In this milieu, Giacometti’s interest in art is nurtured from an early age: in 1915 he completes his first oil painting, in his father’s studio, and just a year later he models portrait busts of his brothers.1 Giacometti soon realizes that he wants to become an artist. In 1919 he leaves his Protestant boarding school in Schiers, near Chur, and moves to Geneva to study fine art. In 1922 he goes to Paris, then the center of the art world, where he studies life drawing, as well as sculpture under Antoine Bourdelle, at the renowned Académie de la Grande Chaumière. He also pays frequent visits to the Louvre to sketch. In 1925 Giacometti has his first exhibition, at the Salon des Tuileries, with two works: a torso and a head of his brother Diego. In the same year, Diego follows his elder brother to Paris. He will model for Alberto for the rest of his life, and from 1929 on also acts as his assistant. In December 1926, Giacometti moves into a new studio at 46, rue Hippolyte-Maindron. The studio is cramped and humble, but he will work there to the last. -

Moments in Time: Lithographs from the HWS Art Collection

IN TIME LITHOGRAPHS FROM THE HWS ART COLLECTION PATRICIA MATHEWS KATHRYN VAUGHN ESSAYS BY: SARA GREENLEAF TIMOTHY STARR ‘08 DIANA HAYDOCK ‘09 ANNA WAGER ‘09 BARRY SAMAHA ‘10 EMILY SAROKIN ‘10 GRAPHIC DESIGN BY: ANNE WAKEMAN ‘09 PHOTOGRAPHY BY: LAUREN LONG HOBART & WILLIAM SMITH COLLEGES 2009 MOMENTS IN TIME: LITHOGRAPHS FROM THE HWS ART COLLECTION HIS EXHIBITION IS THE FIRST IN A SERIES INTENDED TO HIGHLIGHT THE HOBART AND WILLIAM SMITH COLLEGES ART COLLECTION. THE ART COLLECTION OF HOBART TAND WILLIAM SMITH COLLEGES IS FOUNDED ON THE BELIEF THAT THE STUDY AND APPRECIATION OF ORIGINAL WORKS OF ART IS AN INDISPENSABLE PART OF A LIBERAL ARTS EDUCATION. IN LIGHT OF THIS EDUCATIONAL MISSION, WE OFFERED AN INTERNSHIP FOR ONE-HALF CREDIT TO STUDENTS OF HIGH STANDING TO RESEARCH AND WRITE THE CATALOGUE ENTRIES, UNDER OUR SUPERVISION, FOR EACH OBJECT IN THE EXHIBITION. THIS GAVE STUDENTS THE OPPORTUNITY TO LEARN MUSEUM PRACTICE AS WELL AS TO ADD A PUBLICATION FOR THEIR RÉSUMÉ. FOR THIS FIRST EXHIBITION, WE HAVE CHOSEN TO HIGHLIGHT SOME OF THE MORE IMPORTANT ARTISTS IN OUR LARGE COLLECTION OF LITHOGRAPHS AS WELL AS TO HIGHLIGHT A PRINT MEDIUM THAT PLAYED AN INFLUENTIAL ROLE IN THE DEVELOPMENT AND DISSEMINATION OF MODERN ART. OUR PRINT COLLECTION IS THE RICHEST AREA OF THE HWS COLLECTION, AND THIS EXHIBITION GIVES US THE OPPORTUNITY TO HIGHLIGHT SOME OF OUR MAJOR CONTRIBUTORS. ROBERT NORTH HAS BEEN ESPECIALLY GENER- OUS. IN THIS SMALL EXHIBITION ALONE, HE HAS DONATED, AMONG OTHERS, WORKS OF THE WELL-KNOWN ARTISTS ROMARE BEARDEN, GEORGE BELLOWS OF WHICH WE HAVE TWELVE, AND THOMAS HART BENTON – THE GREAT REGIONALIST ARTIST AND TEACHER OF JACKSON POLLOCK. -

Divisionismo La Rivoluzione Della Luce

DIVISIONISMO LA RIVOLUZIONE DELLA LUCE a cura di Annie-Paule Quinsac Novara, Castello Visconteo Sforzesco 23.11.2019 - 05.04.2020 Il Comune di Novara, la Fondazione Castello Visconteo e l’associazione METS Percorsi d’arte hanno in programma per l’autunno e l’inverno 2019-2020 nelle sale dell’imponente sede del Castello Visconteo Sfor- zesco – ristrutturate a regole d’arte per una vocazione museale – un’im- Gaetano Previati Maternità 1 DELLA LUCE LA RIVOLUZIONE DIVISIONISMO portante mostra dedicata al Divisionismo, un movimento giustamente considerato prima avanguardia in Italia. Per la sua posizione geografica, a 45 km dal Monferrato, fonte iconografica imprescindibile nell’opera di Angelo Morbelli (1853-1919), e appena più di cento dalla Volpedo di Giuseppe Pellizza (1868-1907) – senza dimenticare la Valle Vigezzo di Carlo Fornara (1871-1968) che fino a pochi anni era amministrativa- mente sotto la sua giurisdizione – Novara, infatti, è luogo deputato per ospitare questa rassegna. Sono appunto i rapporti con il territorio che hanno determinato le scelte e il taglio della manifestazione. incentrata sul Divisionismo lombardo-piemontese. Giovanni Segantini All’ovile 2 DELLA LUCE LA RIVOLUZIONE DIVISIONISMO La curatela è stata affidata ad Annie-Paule Quinsac, tra i primissimi storici dell’arte ad essersi dedicata al Divisionismo sul finire degli anni Sessanta del secolo scorso, esperta in particolare di Giovanni Segantini – figura che ha dominato l’arte europea dagli anni Novanta alla Prima guerra mondiale –, del vigezzino Carlo Fornara e di Vittore Grubicy de Dragon, artisti ai quali la studiosa ha dedicato fondamentali pubblicazio- ni ed esposizioni. Il Divisionismo nasce a Milano, sulla stessa premessa del Neo-Im- pressionnisme francese (meglio noto come Pointillisme), senza tuttavia Carlo Fornara Fontanalba 3 DELLA LUCE LA RIVOLUZIONE DIVISIONISMO Angelo Morbelli Meditazione Emilio Longoni Bambino con trombetta e cavallino 4 DELLA LUCE LA RIVOLUZIONE DIVISIONISMO che si possa parlare di influenza diretta. -

Alberto Giacometti and the Crisis of the Monument, 1935–45 A

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Hollow Man: Alberto Giacometti and the Crisis of the Monument, 1935–45 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Art History by Joanna Marie Fiduccia 2017 Ó Copyright by Joanna Marie Fiduccia 2017 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Hollow Man: Alberto Giacometti and the Crisis of the Monument, 1935–45 by Joanna Marie Fiduccia Doctor of Philosophy in Art History University of California, Los Angeles, 2017 Professor George Thomas Baker, Chair This dissertation presents the first extended analysis of Alberto Giacometti’s sculpture between 1935 and 1945. In 1935, Giacometti renounced his abstract Surrealist objects and began producing portrait busts and miniature figures, many no larger than an almond. Although they are conventionally dismissed as symptoms of a personal crisis, these works unfold a series of significant interventions into the conventions of figurative sculpture whose consequences persisted in Giacometti’s iconic postwar work. Those interventions — disrupting the harmonious relationship of surface to interior, the stable scale relations between the work and its viewer, and the unity and integrity of the sculptural body — developed from Giacometti’s Surrealist experiments in which the production of a form paradoxically entailed its aggressive unmaking. By thus bridging Giacometti’s pre- and postwar oeuvres, this decade-long interval merges two ii distinct accounts of twentieth-century sculpture, each of which claims its own version of Giacometti: a Surrealist artist probing sculpture’s ambivalent relationship to the everyday object, and an Existentialist sculptor invested in phenomenological experience. This project theorizes Giacometti’s artistic crisis as the collision of these two models, concentrated in his modest portrait busts and tiny figures. -

Relazione Sulla Gestione 2012

2012 BILANCIO D’ESERCIZIO BILANCIO D’ESERCIZIO AL 31 DICEMBRE 2012 In copertina: Carlo Fornara, Il seminatore, 1895, olio su tela, cm. 26,5 x 34 - collezione d’arte della Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Tortona ___________________________________________________________________________________________________________ 2 FONDAZIONE CASSA DI RISPARMIO DI TORTONA BILANCIO D’ESERCIZIO AL 31 DICEMBRE 2012 SOMMARIO 4 Relazione sulla gestione 157 Prospetti di bilancio 159 Nota integrativa 209 Relazione del Collegio dei Revisori ___________________________________________________________________________________________________________ 3 FONDAZIONE CASSA DI RISPARMIO DI TORTONA BILANCIO D’ESERCIZIO AL 31 DICEMBRE 2012 RELAZIONE SULLA GESTIONE INTRODUZIONE – QUADRO NORMATIVO DI RIFERIMENTO Il 31 dicembre 2012 si è chiuso il ventunesimo esercizio della Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Tortona. Il quadro di riferimento normativo relativo allo scorso esercizio è stato caratterizzato da numerosi interventi legislativi che hanno inciso, in alcuni casi significativamente, sull’attività delle fondazioni bancarie. Di seguito una breve panoramica su tali novità. Governance delle Fondazioni L’art. 27-quater della legge n. 27/2012 ha apportato alcune integrazioni all’art. 4, comma 1, del D. Lgs. n. 153/99. In particolare, in tema di requisiti dei componenti l’Organo di Indirizzo delle Fondazioni, viene previsto il ricorso a modalità di designazione ispirate a criteri oggettivi e trasparenti, improntati alla valorizzazione dei principi di onorabilità e professionalità. Viene poi inserita una ulteriore ipotesi di incompatibilità riferita ai soggetti che svolgono funzioni di indirizzo, amministrazione, direzione e controllo presso le Fondazioni: trattasi dell’impossibilità, per tali soggetti, di assumere od esercitare cariche negli organi gestionali, di sorveglianza e di controllo o funzioni di direzione di società concorrenti della società bancaria conferitaria o di società del gruppo. -

Giovanni Segantini

NOTIZIARIO Giovanni Cronache aziendali Segantini Luce, colore, lontananza e infinito PREFAZIONE DEL PRESIDENTE PIERO MELAZZINI Riportiamo uno stralcio dalla Relazione di Quest’anno è la volta di Giovanni Segantini, la cui mono- bilancio 2003 grafia, inserita nella parte riservata alla cultura della Relazio- della controllata ne di bilancio dell’esercizio 2003, intende ravvivare il ricordo Banca Popolare di Sondrio di questo straordinario personaggio, nato nel 1858 ad Arco (Suisse) SA di nel Trentino, quindi tra i monti italiani, e morto a soli 41 an- Lugano. Più ni tra quelli svizzeri, sullo Schafberg sopra Pontresina nel esattamente Canton Grigioni. trascriviamo i Anche per Segantini vale quanto si è sempre pensato contributi su Giovanni Segantini, del destino baro, che ha privato l’umanità di grandi della ter- pubblicati nella ra, deceduti nell’età in cui, in genere, incomincia la parabo- parte del fascicolo la ascendente: Alessandro Magno, San Francesco d’Assisi, Blai- riservata alla se Pascal, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Giacomo Leopardi... cultura, curata da Dopo un’adolescenza difficile, Segantini frequentò l’Accade- Pier Carlo Della Ferrera, con saggi di mia di Brera, dove conobbe artisti, letterati, giornalisti dell’ultima Beat Stutzer, Gaspare scapigliatura lombarda. Barbiellini Amidei e Si usa dire che la quantità va a detrimento della qualità. Non è Franco Monteforte, certamente il caso di Segantini, che fu prolifico nella produzione e le preceduti dalla sue opere ebbero un crescente successo all’estero. Ma anche in Italia Prefazione del Presidente questo pittore, caposcuola del divisionismo, che si manifestò nella sua Cavaliere del Lavoro grandezza con l’opera “Alla stanga” (1885), ne ha lasciate non poche. -

Alberto Giacometti

ALBERTO GIACOMETTI ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................... Genius manifest in art Texts by Beat Stutzer, Franco Monteforte, Casimiro Di Crescenzo, Christian Dettwiler Genius manifest in art ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................... Alberto Giacometti, 1901–1966 by Beat Stutzer* Page I: Alberto Giacometti in the courtyard to his atelier in Paris, ca. 1958. This portrait is featured on Switzerland’s 100-franc banknote. On this page: Alberto Giacometti in his atelier in Paris, ca. 1952. Left: Alberto Giacometti’s Self-portrait , ca. 1923. Oil on canvas, on wood: 55 x 32 cm. Kunsthaus Zürich, Alberto Giacometti Foundation. Alberto Giacometti ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................... Virtually every book or article on Alberto bathed in sunlight. Its bare landscape and Giacometti includes some element of tough climate had a great influence on the biography. Some publications illuminate rural population here. The people of Bergell Giacometti’s life through the use of a spe - were used to hardship and deprivation, as cial literary treatment, -

Press Kit Lausanne, 15

Page 1 of 9 Press kit Lausanne, 15. October 2020 Giovanni Giacometti. Watercolors (16.10.2020 — 17.1.2021) Giovanni Giacometti Watercolors (16.10.2020 — 17.1.2021) Contents 1. Press release 2. Media images 3. Artist’s biography 4. Questions for the exhibition curators 5. Public engagement – Public outreach services 6. Museum services: Book- and Giftshop and Le Nabi Café-restaurant 7. MCBA partners and sponsors Contact Florence Dizdari Press coordinator 079 232 40 06 [email protected] Page 2 of 9 Press kit Lausanne, 15. October 2020 Giovanni Giacometti. Watercolors (16.10.2020 — 17.1.2021) 1. Press release MCBA the Musée cantonal des Beaux-Arts of Lausanne conserves many oil paintings and drawings by Giovanni Giacometti, a major artist from the turn of the 20th century and a faithful friend of one of the institution’s great donors, the Lausanne doctor Henri-Auguste Widmer. By putting on display an exceptional group of watercolors, all of them privately owned and almost all unknown outside their home, MCBA is inviting us to discover a lesser known side of Giovanni Giacometti’s remarkable body of work. Giovanni Giacometti (Stampa, 1868 – Glion, 1933) practiced watercolor throughout his life. As with his oil paintings, he found most of his subjects in the landscapes of his native region, Val Bregaglia and Engadin in the Canton of Graubünden. Still another source of inspiration were the members of his family going about their daily activities, as were local women and men busy working in the fields or fishing. The artist turned to watercolor for commissioned works as well. -

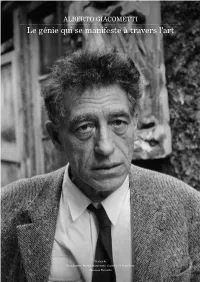

Alberto Giacometti

ALBERTO GIACOMETTI ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................... Le génie qui se manifeste à travers l’art Textes de Beat Stutzer, Franco Monteforte, Casimiro Di Crescenzo, Christian Dettwiler Le génie qui se manifeste à travers l’art ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................... Alberto Giacometti, 1901–1966 par Beat Stutzer* Page I: Alberto Giacometti dans la cour de son atelier à Paris, vers 1958; c’est ce portrait qui figure sur les billets de 100 francs suisses. Sur cette page: Alberto Giacometti dans son atelier parisien, vers 1952. À gauche: Alberto Giacometti, Autoportrait , vers 1923. Huile sur toile sur bois: 55 x 32 cm Kunsthaus Zürich, Fondation Alberto Giacometti. Alberto Giacometti ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................... Parmi la multitude de publications consa - population paysanne. La région a rarement crées à Alberto Giacometti, rares sont pu offrir de quoi vivre à ses fils, souvent celles qui ne proposent pas de biographie contraints d’émigrer pour gagner leur plus ou moins détaillée de l’artiste. Ce sont vie ailleurs, -

La Famiglia Giacometti

La famiglia Giacometti Autor(en): Lietha, Walter Objekttyp: Article Zeitschrift: Quaderni grigionitaliani Band (Jahr): 75 (2006) Heft 2 PDF erstellt am: 11.10.2021 Persistenter Link: http://doi.org/10.5169/seals-57296 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch WALTER LIETHA Traduzione a cura di Nicola Zala La famiglia Giacometti Sulla storia della famiglia bregagliotta Giacometti si contano sinora studi e pubblicazioni riguardanti solo la cerchia parentale del famoso artista. Anche queste, seppur allargate, descrizioni non hanno la pretesa di essere una ricerca familiäre esaustiva. Dovrebbero perö aumentare l'interesse e la conoscenza nei confronti di questa importante famiglia. -

Terra D'ossola.Indb

i Lions ossolani alla propria Terra Hanno collaborato per i testi: Tullio Bertamini, Gianfranco Bianchetti, Paolo Bologna, Paola Caretti, Marco Cattin, Umberto Chiaramonte, Cesarina Masini Chieu, Caterina Bensi Chiovenda, Galeazzo Maria Conti, Paolo Crosa Lenz, Alberto De Giuli, Raffaele Fattalini, Germana Fizzotti, Carmine Gaudiano, Sergio Lucchini, Enrico Margaroli, Cesare Melchiorri, Renzo Mortarotti, Rosario Mosello, Gilberto Oneto, Anna Pagani, Angela Travostino Preioni, Mauro Proverbio, Ettore Radici, Pier Antonio Ragozza, Aldo Roggiani, Enrico Rizzi, Franca Paglino Sgarella, Giacomo Zerbini. Comitato di redazione: Antonio Pagani - Coordinatore generale Paola Caretti - Raffaele Frassetti - Alessandro Grossi - Sergio Lucchini - Giampaolo Prola Consulenti: Tullio Bertamini Fotografie: Carlo Pessina -Agenzia Pessina, Domodossola Copertina: Giampaolo Prola Il Lions Club Domodossola desidera esprimere la propria gratitudine a tutti coloro che, collaborando o contribuendo, hanno reso possibile la realizzazione di quest’opera © Lions Club Domodossola - 2005 Tutti i diritti riservati. Riproduzione anche parziale vietata. Il volume è stato curato dalla Edizioni Grossi - Domodossola Stampato dalla Tipolitografia Saccardo Carlo & Figli s.n.c. - Ornavasso (VB) Sommario pag. 15 La Storia ” 17 Dalla preistoria al traforo del Sempione Tullio Bertamini ” 57 La “repubblica” dell’Ossola Paolo Bologna ” 69 L’archeologia Alberto De Giuli ” 75 Ambiente e natura ” 77 Un paesaggio verticale Renzo Mortarotti ” 87 L’acqua e la pietra Aldo G. Roggiani e Marco Cattin ” 103 Acque termali e acque minerali Pier Antonio Ragozza ” 109 Il clima Tullio Bertamini e Rosario Mosello ” 119 La flora Cesarina Masini Chieu ” 135 La fauna Franca Paglino Sgarella ” 149 I parchi e le riserve naturali Paolo Crosa Lenz ” 155 La cultura ” 157 Ossolani illustri Angela Travostino Preioni ” 195 Antonio Rosmini Anna Pagani ” 203 I monumenti e i segni d’arte Gian Franco Bianchetti ” 231 I letterati ossolani Enrico Margaroli 7 pag. -

Discovering/Uncovering the Modernity of Prehistory

Alberto Giacometti: Prehistoric Art as an Impulse for the Artist’s Late Sculptural Work after 1939 Elke Seibert Alberto Giacometti, one of the most important artists of the twentieth century, was a seeker, grounded in the Swiss Bergell valley and raised in a family of artists. His body of work did not develop in a linear way.1 His biography influenced his phenomeno- logical approach.2 As a painter, draftsman, and sculptor, he simultaneously pursued different form and design types3 in subtly selected materiality.4 He achieved a new be- ginning for figural sculpture,5 initiated by August Rodin. In Paris, he found the friction he needed for his creative process, and, along with Pablo Picasso and Paul Klee, was one of the most influential artists of his era. With a keen wit, Giacometti spent his entire life taking hold of the individual sedi- mentary layers of his personal and artistic development. His recourse to deeper-lying sediment, which he discovered after separating from the Surrealists up until the end 1 Selected works in Giacometti research: Alberto Giacometti, Material und Vision: Die Meisterwerke in Gips, Stein, Ton und Bronze (exh. cat. Kunsthaus Zurich), ed. Philippe Büttner, Zurich/New York 2016; Thierry Dufrêne, Giacometti – Genet: Masken und modernes Portrait, Berlin 2013; Ulf Küster, Alberto Giacometti: Raum, Figur, Zeit, Ostfildern 2009;L`Atelier Giacometti: Collection de la Fondation Alberto et Annette Gia- cometti (exh. cat. Musée national d’art moderne/Centre Georges Pompidou), ed. Véronique Wiesinger, Paris 2007; Ernst Scheiddegger, Spuren einer Freundschaft, Zurich 1990; Alberto Giacometti (exh. cat. Na- tionalgalerie Berlin/Staatsgalerie Stuttgart), ed.