Discovering/Uncovering the Modernity of Prehistory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alberto Giacometti: a Biography Sylvie Felber

Alberto Giacometti: A Biography Sylvie Felber Alberto Giacometti is born on October 10, 1901, in the village of Borgonovo near Stampa, in the valley of Bregaglia, Switzerland. He is the eldest of four children in a family with an artistic background. His mother, Annetta Stampa, comes from a local landed family, and his father, Giovanni Giacometti, is one of the leading exponents of Swiss Post-Impressionist painting. The well-known Swiss painter Cuno Amiet becomes his godfather. In this milieu, Giacometti’s interest in art is nurtured from an early age: in 1915 he completes his first oil painting, in his father’s studio, and just a year later he models portrait busts of his brothers.1 Giacometti soon realizes that he wants to become an artist. In 1919 he leaves his Protestant boarding school in Schiers, near Chur, and moves to Geneva to study fine art. In 1922 he goes to Paris, then the center of the art world, where he studies life drawing, as well as sculpture under Antoine Bourdelle, at the renowned Académie de la Grande Chaumière. He also pays frequent visits to the Louvre to sketch. In 1925 Giacometti has his first exhibition, at the Salon des Tuileries, with two works: a torso and a head of his brother Diego. In the same year, Diego follows his elder brother to Paris. He will model for Alberto for the rest of his life, and from 1929 on also acts as his assistant. In December 1926, Giacometti moves into a new studio at 46, rue Hippolyte-Maindron. The studio is cramped and humble, but he will work there to the last. -

Moments in Time: Lithographs from the HWS Art Collection

IN TIME LITHOGRAPHS FROM THE HWS ART COLLECTION PATRICIA MATHEWS KATHRYN VAUGHN ESSAYS BY: SARA GREENLEAF TIMOTHY STARR ‘08 DIANA HAYDOCK ‘09 ANNA WAGER ‘09 BARRY SAMAHA ‘10 EMILY SAROKIN ‘10 GRAPHIC DESIGN BY: ANNE WAKEMAN ‘09 PHOTOGRAPHY BY: LAUREN LONG HOBART & WILLIAM SMITH COLLEGES 2009 MOMENTS IN TIME: LITHOGRAPHS FROM THE HWS ART COLLECTION HIS EXHIBITION IS THE FIRST IN A SERIES INTENDED TO HIGHLIGHT THE HOBART AND WILLIAM SMITH COLLEGES ART COLLECTION. THE ART COLLECTION OF HOBART TAND WILLIAM SMITH COLLEGES IS FOUNDED ON THE BELIEF THAT THE STUDY AND APPRECIATION OF ORIGINAL WORKS OF ART IS AN INDISPENSABLE PART OF A LIBERAL ARTS EDUCATION. IN LIGHT OF THIS EDUCATIONAL MISSION, WE OFFERED AN INTERNSHIP FOR ONE-HALF CREDIT TO STUDENTS OF HIGH STANDING TO RESEARCH AND WRITE THE CATALOGUE ENTRIES, UNDER OUR SUPERVISION, FOR EACH OBJECT IN THE EXHIBITION. THIS GAVE STUDENTS THE OPPORTUNITY TO LEARN MUSEUM PRACTICE AS WELL AS TO ADD A PUBLICATION FOR THEIR RÉSUMÉ. FOR THIS FIRST EXHIBITION, WE HAVE CHOSEN TO HIGHLIGHT SOME OF THE MORE IMPORTANT ARTISTS IN OUR LARGE COLLECTION OF LITHOGRAPHS AS WELL AS TO HIGHLIGHT A PRINT MEDIUM THAT PLAYED AN INFLUENTIAL ROLE IN THE DEVELOPMENT AND DISSEMINATION OF MODERN ART. OUR PRINT COLLECTION IS THE RICHEST AREA OF THE HWS COLLECTION, AND THIS EXHIBITION GIVES US THE OPPORTUNITY TO HIGHLIGHT SOME OF OUR MAJOR CONTRIBUTORS. ROBERT NORTH HAS BEEN ESPECIALLY GENER- OUS. IN THIS SMALL EXHIBITION ALONE, HE HAS DONATED, AMONG OTHERS, WORKS OF THE WELL-KNOWN ARTISTS ROMARE BEARDEN, GEORGE BELLOWS OF WHICH WE HAVE TWELVE, AND THOMAS HART BENTON – THE GREAT REGIONALIST ARTIST AND TEACHER OF JACKSON POLLOCK. -

Alberto Giacometti and the Crisis of the Monument, 1935–45 A

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Hollow Man: Alberto Giacometti and the Crisis of the Monument, 1935–45 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Art History by Joanna Marie Fiduccia 2017 Ó Copyright by Joanna Marie Fiduccia 2017 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Hollow Man: Alberto Giacometti and the Crisis of the Monument, 1935–45 by Joanna Marie Fiduccia Doctor of Philosophy in Art History University of California, Los Angeles, 2017 Professor George Thomas Baker, Chair This dissertation presents the first extended analysis of Alberto Giacometti’s sculpture between 1935 and 1945. In 1935, Giacometti renounced his abstract Surrealist objects and began producing portrait busts and miniature figures, many no larger than an almond. Although they are conventionally dismissed as symptoms of a personal crisis, these works unfold a series of significant interventions into the conventions of figurative sculpture whose consequences persisted in Giacometti’s iconic postwar work. Those interventions — disrupting the harmonious relationship of surface to interior, the stable scale relations between the work and its viewer, and the unity and integrity of the sculptural body — developed from Giacometti’s Surrealist experiments in which the production of a form paradoxically entailed its aggressive unmaking. By thus bridging Giacometti’s pre- and postwar oeuvres, this decade-long interval merges two ii distinct accounts of twentieth-century sculpture, each of which claims its own version of Giacometti: a Surrealist artist probing sculpture’s ambivalent relationship to the everyday object, and an Existentialist sculptor invested in phenomenological experience. This project theorizes Giacometti’s artistic crisis as the collision of these two models, concentrated in his modest portrait busts and tiny figures. -

Alberto Giacometti

ALBERTO GIACOMETTI ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................... Genius manifest in art Texts by Beat Stutzer, Franco Monteforte, Casimiro Di Crescenzo, Christian Dettwiler Genius manifest in art ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................... Alberto Giacometti, 1901–1966 by Beat Stutzer* Page I: Alberto Giacometti in the courtyard to his atelier in Paris, ca. 1958. This portrait is featured on Switzerland’s 100-franc banknote. On this page: Alberto Giacometti in his atelier in Paris, ca. 1952. Left: Alberto Giacometti’s Self-portrait , ca. 1923. Oil on canvas, on wood: 55 x 32 cm. Kunsthaus Zürich, Alberto Giacometti Foundation. Alberto Giacometti ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................... Virtually every book or article on Alberto bathed in sunlight. Its bare landscape and Giacometti includes some element of tough climate had a great influence on the biography. Some publications illuminate rural population here. The people of Bergell Giacometti’s life through the use of a spe - were used to hardship and deprivation, as cial literary treatment, -

Press Kit Lausanne, 15

Page 1 of 9 Press kit Lausanne, 15. October 2020 Giovanni Giacometti. Watercolors (16.10.2020 — 17.1.2021) Giovanni Giacometti Watercolors (16.10.2020 — 17.1.2021) Contents 1. Press release 2. Media images 3. Artist’s biography 4. Questions for the exhibition curators 5. Public engagement – Public outreach services 6. Museum services: Book- and Giftshop and Le Nabi Café-restaurant 7. MCBA partners and sponsors Contact Florence Dizdari Press coordinator 079 232 40 06 [email protected] Page 2 of 9 Press kit Lausanne, 15. October 2020 Giovanni Giacometti. Watercolors (16.10.2020 — 17.1.2021) 1. Press release MCBA the Musée cantonal des Beaux-Arts of Lausanne conserves many oil paintings and drawings by Giovanni Giacometti, a major artist from the turn of the 20th century and a faithful friend of one of the institution’s great donors, the Lausanne doctor Henri-Auguste Widmer. By putting on display an exceptional group of watercolors, all of them privately owned and almost all unknown outside their home, MCBA is inviting us to discover a lesser known side of Giovanni Giacometti’s remarkable body of work. Giovanni Giacometti (Stampa, 1868 – Glion, 1933) practiced watercolor throughout his life. As with his oil paintings, he found most of his subjects in the landscapes of his native region, Val Bregaglia and Engadin in the Canton of Graubünden. Still another source of inspiration were the members of his family going about their daily activities, as were local women and men busy working in the fields or fishing. The artist turned to watercolor for commissioned works as well. -

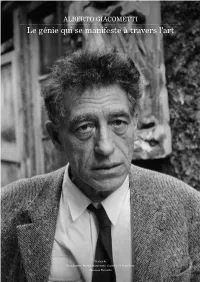

Alberto Giacometti

ALBERTO GIACOMETTI ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................... Le génie qui se manifeste à travers l’art Textes de Beat Stutzer, Franco Monteforte, Casimiro Di Crescenzo, Christian Dettwiler Le génie qui se manifeste à travers l’art ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................... Alberto Giacometti, 1901–1966 par Beat Stutzer* Page I: Alberto Giacometti dans la cour de son atelier à Paris, vers 1958; c’est ce portrait qui figure sur les billets de 100 francs suisses. Sur cette page: Alberto Giacometti dans son atelier parisien, vers 1952. À gauche: Alberto Giacometti, Autoportrait , vers 1923. Huile sur toile sur bois: 55 x 32 cm Kunsthaus Zürich, Fondation Alberto Giacometti. Alberto Giacometti ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................... Parmi la multitude de publications consa - population paysanne. La région a rarement crées à Alberto Giacometti, rares sont pu offrir de quoi vivre à ses fils, souvent celles qui ne proposent pas de biographie contraints d’émigrer pour gagner leur plus ou moins détaillée de l’artiste. Ce sont vie ailleurs, -

La Famiglia Giacometti

La famiglia Giacometti Autor(en): Lietha, Walter Objekttyp: Article Zeitschrift: Quaderni grigionitaliani Band (Jahr): 75 (2006) Heft 2 PDF erstellt am: 11.10.2021 Persistenter Link: http://doi.org/10.5169/seals-57296 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch WALTER LIETHA Traduzione a cura di Nicola Zala La famiglia Giacometti Sulla storia della famiglia bregagliotta Giacometti si contano sinora studi e pubblicazioni riguardanti solo la cerchia parentale del famoso artista. Anche queste, seppur allargate, descrizioni non hanno la pretesa di essere una ricerca familiäre esaustiva. Dovrebbero perö aumentare l'interesse e la conoscenza nei confronti di questa importante famiglia. -

Tate Modern Reunites Rarely Seen Plaster Sculptures by Giacometti

PRESS RELEASE 23 January 2017 TATE MODERN REUNITES RARELY SEEN PLASTER SCULPTURES BY GIACOMETTI A celebrated group of plaster sculptures will be brought together for the first time since they were made in 1956 for Tate Modern’s major Giacometti retrospective. All six Women of Venice plaster works created for the 1956 Venice Biennale will be reunited for the first time in 60 years. They will be shown alongside two further plaster sculptures from this series, which Giacometti unveiled at the Kunsthalle Berne that same year. The works have been specially restored and reassembled for Tate Modern’s exhibition by the Fondation Alberto et Annette Giacometti, Paris. It will offer a once in the lifetime opportunity to see this important group of fragile works as the artist originally intended. Giacometti was chosen to represent France at the 1956 Venice Biennale. He showed a group of newly made plaster sculptures for the exhibition, all of which depict an elongated standing female nude. These works represent a crucial stage in Giacometti’s artistic development and were the result of the study of his wife Annette, one of his most important models. The sculptures can be seen as a culmination of the artist’s lifelong experimentations to depict the reality of the human form. While Giacometti is best known for his bronze figures, Tate Modern will reposition him as an artist with a far wider interest in materials and textures, especially plaster, clay and paint. Over the course of about three weeks, Giacometti moulded each of the Women of Venice in clay Woman of Venice V, 1956 © Alberto before casting them in plaster and reworking them with a knife to further Giacometti estate / ACS and DACS in accentuate their surface. -

Admission Coming Soon

Reciprocal portraits Useful information Hodler, Segantini, Giacometti and Amiet Palais Lumière Evian (quai Charles-Albert Besson). painted self-portraits, a classic subject in Open daily 10am-6pm (Monday, Tuesday 2pm-6pm) and bank holidays. art. They also produced a collection of Open Tuesday morning during half-term. mirror portraits depicting each other. Tel: +33 (0)4 50 83 15 90 / www.ville-evian.fr These reciprocal portraits enabled them to pay tribute to the master e.g. Scientific curator & scenography: Corsin Vogel, an artist from the Grisons, associate profes- Giacometti or Amiet depicting Segantini sor at the Ecole Nationale Supérieure Louis-Lumière, Saint-Denis. or Hodler respectively on their death Curator: William Saadé, honorary head curator for heritage, artistic advisor for the Palais Lumière. beds. They also reflect the bond between two close artists: Giacometti and Amiet painted each other in their little Paris Admission - Guided tours for the general public daily at 2.30pm: €4 in addition to admission fee. apartment, Amiet portrayed his friend - Standard: €8; - Concessions: €6 (for details about discounts, see www. Hodler in front of his own pieces or as a Tickets: ville-evian.fr); - From the exhibition reception. sculpture. Giacometti never tired of - Free for under 16s; - On: ville-evian.tickeasy.com. - 30% off admission to exhibitions on presentation of a painting and drawing his family, espe- - From the FNAC network and on www.fnac.com. ticket for the Pierre Gianadda Foundation in Martigny; - From CGN outlets (boats and ticket offices). cially Alberto. Amiet did the same with Hannes & Corsin Vogel : Den See sehen (See the lake), 2013 © Private collection. -

The Art of Alberto Giacometti for the First Time in the Czech Republic

THE ART OF ALBERTO GIACOMETTI FOR THE FIRST TIME IN THE CZECH REPUBLIC 10 July 2019 – For the very first time in the Czech Republic, the National Gallery Prague presents the work of one of the most important, influential and beloved artists of the 20th century, the sculptor and painter Alberto Giacometti (1901–1966). This extensive retrospective exhibition maps Giacometti’s artistic development across five decades. It follows its course from the artist’s early years in the Swiss town of Stampa, through his avantgarde experiments in inter-war Paris and up to its culmination in the unique manner of figural representation for which the artist is known best. His impressive elongated figures, which Giacometti created after World War II and which carry a sense of existential urgency, reflect his sense for the fragility and vulnerability of the human being. Walking Man, 1960 The Cage, 1950–1951 © Alberto Giacometti Estate, (Fondation Giacometti, Paris + ADAGP, Paris) 2019 ”Thanks to a joint collaboration with the Fondation Giacometti in Paris, who administers the estate of Annette and Alberto Giacometti, we are able to present over one hundred sculptures, including a series of valuable plaster statuettes, to the Czech audience. The exhibition will also feature several of Giacometti’s key paintings and drawings that testify to the breadth of his technical ability and thematic ambit,” says Julia Bailey, the exhibition’s curator from the NGP’s Collection of Modern and Contemporary Art. The exhibition at the Trade Fair Palace will feature such notable examples of Giacometti’s works as Walking Man, Standing Woman or his Women of Venice, which intrigued audiences at the famous Italian Biennale in 1956, as well as several other of his iconic works such as Spoon Woman, Woman with Chariot, Nose and valuable miniature plaster sculptures, intimate portraits of the artist’s family and friends who have been Giacometti’s favourite models all life long. -

Sisley's Skies Giacometti's Engadin Amiet in Blue And

2|19 Sisley’s Giacometti’s Amiet in skies Engadin blue and red PAGES 10/11 PAGES 12/13 PAGES 14/15 Ladies and gentlemen, Dear clients and friends, Ferdinand Hodler’s elegiac female figures are one of the artist’s hallmarks, and have become icons of Swiss modern art. Through Hodler’s constant re-examination of the motif, they eventually became representations of fate. With these works, the artist suggests emotions and at the same time pays homage to infinity and beauty. Illustrated on the cover of this issue, “Die Schreitende” (“The pacing woman”, which shows Hodler’s model Giulia Leonardi) was painted around 1912, at the zenith of his artistic career. It will be offered in our 28 June auction of Swiss Art, which features a comprehensive overview of 19th- and early 20th-century Swiss painting, including practically all of the great names from this period. Also of special note is Giovanni Giacometti’s four-part panorama of the Swiss Engadine from Muottas Muragl over the snow-capped peaks and green mountain valleys of the Engadine – as far as the eye can see (p. 12). Like Hodler and Giacometti, their contemporary Cuno Amiet was popular with private art collectors. The Swiss department store entrepreneur and friend of Amiet, Eugen Loeb, acquired numerous examples of his work, including the expressive “Apple Harvest in Blue and Red” (p. 14), another highlight of the Swiss Art auction on 28 June. Also on 28 June, we will offer an auction of works by Impressionist and Modern artists, featuring a wonderful landscape by the great Impressionist Alfred Sisley (p. -

Alberto Giacometti a Casa»

«ALBERTO GIACOMETTI A CASA» Ciäsa Granda und Atelier Alberto Giacometti Stampa 5 giugno – 16 ottobre 2016 Bruna Ruinelli, presidente della Società culturale di Bregaglia, sezione Pgi Nel cinquantesimo della morte di Alberto Giacometti la Società culturale, sezione Pgi presenta nella Ciäsa Granda, museo etnografico della Valle, e nell’Atelier di Giovanni e di Alberto Giacometti la mostra «Alberto Giacometti. A casa» Le opere esposte simboleggiano il rapporto costante che uno tra i maggiori esponenti del novecento artistico ha mantenuto con il luogo in cui è nato. Attraverso risvolti familiari e temi legati all’ambiente dove è cresciuto, la mostra rivisita l’intero percorso artistico di Alberto Giacometti. Essa comprende opere realizzate tra gli anni Venti e gli anni Sessanta, il periodo più creativo del celebre artista. «Alberto Giacometti. A casa» riempie lo spazio espositivo della Ciäsa Granda compreso tra le due opere che sono parte della collezione permanente: i ciottoli in scisto del fiume Landquart su cui sono incisi i visi di Socrate e di Gottfried Keller realizzati dal giovane Alberto ancora liceale a Schiers e l’opera ultima del grande artista creata a Parigi prima del suo ricovero a Coira, il bronzo di Eli Lotar III originariamente posto sulla sua tomba a Borgonovo. Simili a tasselli di un puzzle le varie sculture, i disegni e i dipinti provenienti da diversi Musei d’arte e da collezioni private ci parlano di Alberto Giacometti uomo e artista nell’instancabile tentativo di rappresentare la realtà attraverso la percezione del soggetto quale somma di quanto succede attorno a sé e in sé. Arricchita dagli scatti di Ernst Scheidegger la mostra non poteva che approfondire il legame che ha unito i due uomini, la loro passione, la loro amicizia.