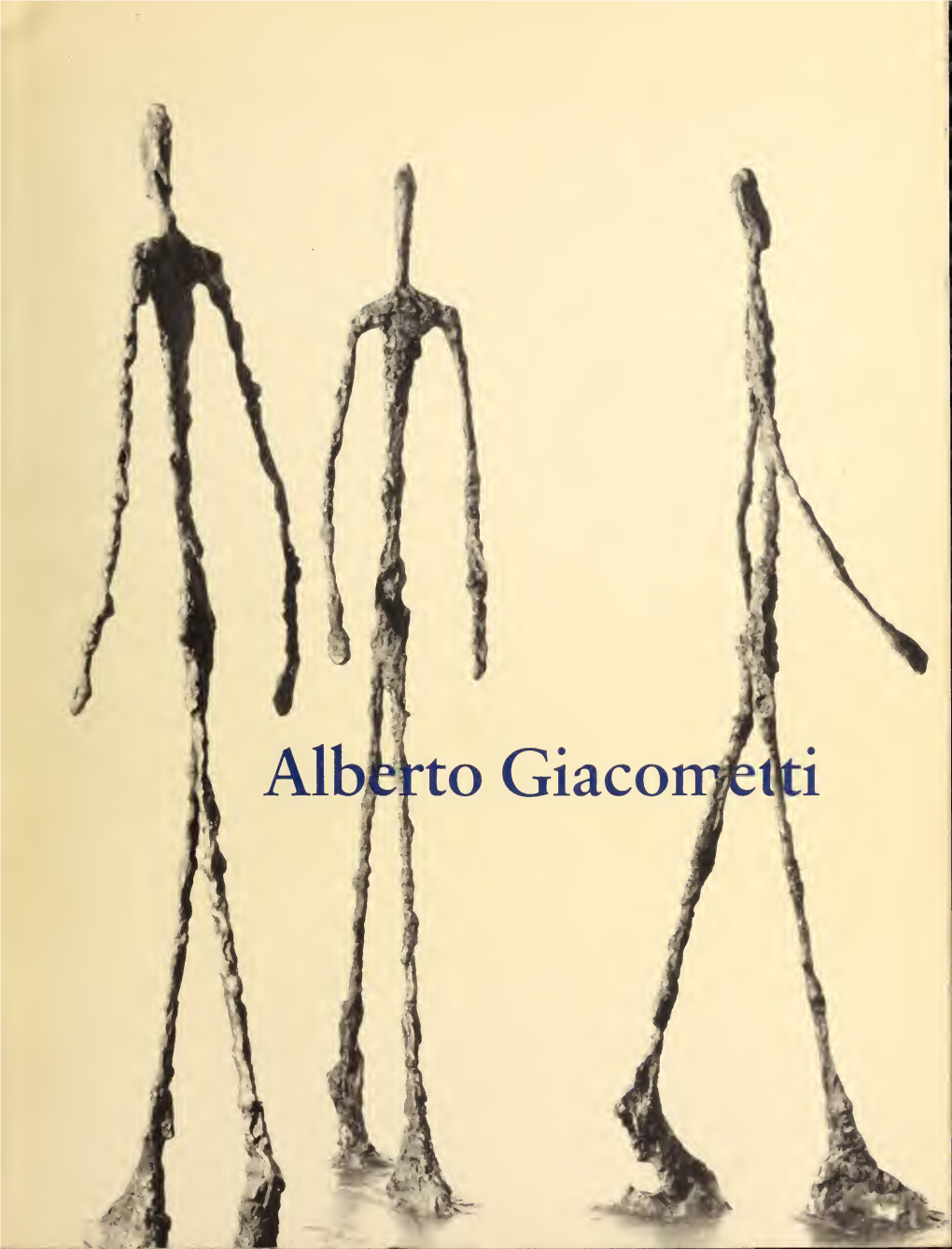

Alberto Giacometti

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Art Collection of Peter Watson (1908–1956)

099-105dnh 10 Clark Watson collection_baj gs 28/09/2015 15:10 Page 101 The BRITISH ART Journal Volume XVI, No. 2 The art collection of Peter Watson (1908–1956) Adrian Clark 9 The co-author of a ously been assembled. Generally speaking, he only collected new the work of non-British artists until the War, when circum- biography of Peter stances forced him to live in London for a prolonged period and Watson identifies the he became familiar with the contemporary British art world. works of art in his collection: Adrian The Russian émigré artist Pavel Tchelitchev was one of the Clark and Jeremy first artists whose works Watson began to collect, buying a Dronfield, Peter picture by him at an exhibition in London as early as July Watson, Queer Saint. 193210 (when Watson was twenty-three).11 Then in February The cultured life of and March 1933 Watson bought pictures by him from Tooth’s Peter Watson who 12 shook 20th-century in London. Having lived in Paris for considerable periods in art and shocked high the second half of the 1930s and got to know the contempo- society, John Blake rary French art scene, Watson left Paris for London at the start Publishing Ltd, of the War and subsequently dispatched to America for safe- pp415, £25 13 ISBN 978-1784186005 keeping Picasso’s La Femme Lisant of 1934. The picture came under the control of his boyfriend Denham Fouts.14 eter Watson According to Isherwood’s thinly veiled fictional account,15 (1908–1956) Fouts sold the picture to someone he met at a party for was of consid- P $9,500.16 Watson took with him few, if any, pictures from Paris erable cultural to London and he left a Romanian friend, Sherban Sidery, to significance in the look after his empty flat at 44 rue du Bac in the VIIe mid-20th-century art arrondissement. -

Gordon Onslow Ford Voyager and Visionary

Gordon Onslow Ford Voyager and Visionary 11 February – 13 May 2012 The Mint Museum 1 COVER Gordon Onslow Ford, Le Vallee, Switzerland, circa 1938 Photograph by Elisabeth Onslow Ford, courtesy of Lucid Art Foundation FIGURE 1 Sketch for Escape, October 1939 gouache on paper Photograph courtesy of Lucid Art Foundation Gordon Onslow Ford: Voyager and Visionary As a young midshipman in the British Royal Navy, Gordon Onslow Ford (1912-2003) welcomed standing the night watch on deck, where he was charged with determining the ship’s location by using a sextant to take readings from the stars. Although he left the navy, the experience of those nights at sea may well have been the starting point for the voyages he was to make in his painting over a lifetime, at first into a fabricated symbolic realm, and even- tually into the expanding spaces he created on his canvases. The trajectory of Gordon Onslow Ford’s voyages began at his birth- place in Wendover, England and led to the Royal Naval College at Dartmouth and to three years at sea as a junior officer in the Mediterranean and Atlantic fleets of the British Navy. He resigned from the navy in order to study art in Paris, where he became the youngest member of the pre-war Surrealist group. At the start of World War II, he returned to England for active duty. While in London awaiting a naval assignment, he organized a Surrealist exhibition and oversaw the publication of Surrealist poetry and artworks that had been produced the previous summer in France (fig. -

Henri Matisse's the Italian Woman, by Pierre

Guggenheim Museum Archives Reel-to-Reel collection Hilla Rebay Lecture: Henri Matisse’s The Italian Woman, by Pierre Schneider, 1982 PART 1 THOMAS M. MESSER Good evening, ladies and gentlemen, and welcome to the third lecture within the Hilla Rebay Series. As you know, it is dedicated to a particular work of art, and so I must remind you that last spring, the Museum of Modern Art here in New York, and the Guggenheim, engaged in something that I think may be called, without exaggeration, a historic exchange of masterpieces. We agreed to complete MoMA’s Kandinsky seasons, because the Campbell panels that I ultimately perceived as seasons, had, [00:01:00] until that time, been divided between the Museum of Modern Art and ourselves. We gave them, in other words, fall and winter, to complete the foursome. In exchange, we received, from the Museum of Modern Art, two very important paintings: a major Picasso Still Life of the early 1930s, and the first Matisse ever to enter our collection, entitled The Italian Woman. The public occasion has passed. We have, for the purpose, reinstalled the entire Thannhauser wing, and I'm sure that you have had occasion to see how the Matisse and the new Picasso have been included [00:02:00] in our collection. It seemed appropriate to accompany this public gesture with a scholarly event, and we have therefore, decided this year, to devote the Hilla Rebay Lecture to The Italian Woman. Naturally, we had to find an appropriate speaker for the event and it did not take us too long to come upon Pierre Schneider, who resides in Paris and who has agreed to make his very considerable Matisse expertise available for this occasion. -

L'été Giacometti À La Fondation Maeght by Michel Gathier

www.smartymagazine.com L'été Giacometti à la Fondation Maeght by Michel Gathier >> SAINT-PAUL-DE-VENCE Toujours chez Alberto Giacometti revient ce fil incandescent de la sculpture comme si celle-ci, de ses mains, se réconciliait avec son point d'origine, délivrée de sa matière, réduite à la seule vérité du nerf qui l'organise et lui donne vie. Alberto Giacometti est à la fois celui qui parle de l'origine et qui trace un autre chemin. « L'homme qui marche » est pétri de cendre et, tel le chien ou le chat de ses sculptures, il renifle des miettes de lumière pour continuer à vivre. La lumière, ce fut son père Giovanni qui, dans la peinture, la célébra. Né en 1868, il inaugura une lignée familiale d'artistes qui durant plus d'un siècle perpétua cette croyance en l'art, cette volonté folle de découvrir la vérité du monde. La Fondation Maeght nous raconte aujourd'hui cette histoire-là qui est celle du feu et de la cendre, celle des braises qui nourrissent de nouvelles flammes pour croire en la vie. Cette aventure s'incarne dans cette famille qui, dans la peinture, la sculpture, la décoration ou l’architecture, embrassa le monde de sa passion créatrice. Giovanni eut trois fils. Alberto, l'aîné, rayonne encore du bronze de ses sculptures émaciées et son œuvre s'expose aujourd'hui à Saint Paul de Vence comme au Forum Grimaldi de Monaco. Entre l'ombre et la lumière, le plein et le vide, il nous place au cœur de l'acte créateur – celui que Nietzsche évoquait dans « La naissance de la tragédie » : l'opposition fondamentale entre le principe apollinien lié à la lumière et au feu et le principe dionysiaque sous les auspices de l'obscurité et de l'effacement. -

Alberto Giacometti: a Biography Sylvie Felber

Alberto Giacometti: A Biography Sylvie Felber Alberto Giacometti is born on October 10, 1901, in the village of Borgonovo near Stampa, in the valley of Bregaglia, Switzerland. He is the eldest of four children in a family with an artistic background. His mother, Annetta Stampa, comes from a local landed family, and his father, Giovanni Giacometti, is one of the leading exponents of Swiss Post-Impressionist painting. The well-known Swiss painter Cuno Amiet becomes his godfather. In this milieu, Giacometti’s interest in art is nurtured from an early age: in 1915 he completes his first oil painting, in his father’s studio, and just a year later he models portrait busts of his brothers.1 Giacometti soon realizes that he wants to become an artist. In 1919 he leaves his Protestant boarding school in Schiers, near Chur, and moves to Geneva to study fine art. In 1922 he goes to Paris, then the center of the art world, where he studies life drawing, as well as sculpture under Antoine Bourdelle, at the renowned Académie de la Grande Chaumière. He also pays frequent visits to the Louvre to sketch. In 1925 Giacometti has his first exhibition, at the Salon des Tuileries, with two works: a torso and a head of his brother Diego. In the same year, Diego follows his elder brother to Paris. He will model for Alberto for the rest of his life, and from 1929 on also acts as his assistant. In December 1926, Giacometti moves into a new studio at 46, rue Hippolyte-Maindron. The studio is cramped and humble, but he will work there to the last. -

Coire, Switzerland 1966

FRENCH SCULPTURE CENSUS / RÉPERTOIRE DE SCULPTURE FRANÇAISE GIACOMETTI, Alberto Borgonovo, Switzerland 1901 - Coire, Switzerland 1966 Maker: Fiorini Foundry, London Femme qui marche [I] Walking Woman [I] 1932, verrsion of 1936, cast in 1955 bronze statue 7 7 59 ?16 x 4 ?16 x 15 in. on the right side of base: ALBERTO GIACOMETTI on the back of base: IV/IV Acc. No.: 64.520 Credit Line: Major Henry Lee Higginson and William Francis Warden Funds Photo credit: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston © Artist : Boston, Massachusetts, Museum of Fine Arts www.mfa.org Provenance 1936, London, the plaster original was sold to Sir Roland Penrose, who sold it to Valerie Cooper 1955, London, Valerie Cooper sold the plaster original to the Hanover Gallery which commissioned an edition of 4 bronze casts from Fiorini's Foundry(London) 1964, April 8, sold by Hanover Gallery to the MFA, Major Henry Lee Higginson and William Francis Warden Funds Bibliography Museum's website, 16 February 2012 and 20 March 2012 1962 Dupin Jacques Dupin, Alberto Giacometti, Paris, 1972, p. 218 1965 Burlington "Giacometti's 'Femme Qui Marche'", The Burlington Magazine, June 1965, p. 338 1970 Huber Carlo Huber, Alberto Giacometti, Lausanne, 1970, p. 40, repr. 1972 Hohl Reinhold Hohl, Alberto Giacometti: Sculpture Painting Drawing, London, 1972, p. 103-104, p. 138-139, p. 300, p. 70, repr. 1981 Ronald Alley Ronald, Catalogue of The Tate Gallery's Collection of Modern Art other than works by British Artists. London, The Tate Gallery in association with Sotheby Parke Bernet, 1981, p. 276- 277 Exhibitions 1965-1966 New York/Chicago/Los Angeles/San Francisco Alberto Giacometti, organized by Peter Selz, New York, The Museum of Modern Art, June 9- october 12, 1965; The Art Institute of Chicago, November 5-December 12, 1965; The Los Angeles County Museum, January 6-February 14, 1966; The San Francisco Museum of Art, March 10- April 24, 1966 1974 New York Alberto Giacometti: A Retrospective Exhibition, New York, The Solomon R. -

André Breton Och Surrealismens Grundprinciper (1977)

Franklin Rosemont André Breton och surrealismens grundprinciper (1977) Översättning Bruno Jacobs (1985) Innehåll Översättarens förord................................................................................................................... 1 Inledande anmärkning................................................................................................................ 2 1.................................................................................................................................................. 3 2.................................................................................................................................................. 8 3................................................................................................................................................ 12 4................................................................................................................................................ 15 5................................................................................................................................................ 21 6................................................................................................................................................ 26 7................................................................................................................................................ 30 8............................................................................................................................................... -

Moments in Time: Lithographs from the HWS Art Collection

IN TIME LITHOGRAPHS FROM THE HWS ART COLLECTION PATRICIA MATHEWS KATHRYN VAUGHN ESSAYS BY: SARA GREENLEAF TIMOTHY STARR ‘08 DIANA HAYDOCK ‘09 ANNA WAGER ‘09 BARRY SAMAHA ‘10 EMILY SAROKIN ‘10 GRAPHIC DESIGN BY: ANNE WAKEMAN ‘09 PHOTOGRAPHY BY: LAUREN LONG HOBART & WILLIAM SMITH COLLEGES 2009 MOMENTS IN TIME: LITHOGRAPHS FROM THE HWS ART COLLECTION HIS EXHIBITION IS THE FIRST IN A SERIES INTENDED TO HIGHLIGHT THE HOBART AND WILLIAM SMITH COLLEGES ART COLLECTION. THE ART COLLECTION OF HOBART TAND WILLIAM SMITH COLLEGES IS FOUNDED ON THE BELIEF THAT THE STUDY AND APPRECIATION OF ORIGINAL WORKS OF ART IS AN INDISPENSABLE PART OF A LIBERAL ARTS EDUCATION. IN LIGHT OF THIS EDUCATIONAL MISSION, WE OFFERED AN INTERNSHIP FOR ONE-HALF CREDIT TO STUDENTS OF HIGH STANDING TO RESEARCH AND WRITE THE CATALOGUE ENTRIES, UNDER OUR SUPERVISION, FOR EACH OBJECT IN THE EXHIBITION. THIS GAVE STUDENTS THE OPPORTUNITY TO LEARN MUSEUM PRACTICE AS WELL AS TO ADD A PUBLICATION FOR THEIR RÉSUMÉ. FOR THIS FIRST EXHIBITION, WE HAVE CHOSEN TO HIGHLIGHT SOME OF THE MORE IMPORTANT ARTISTS IN OUR LARGE COLLECTION OF LITHOGRAPHS AS WELL AS TO HIGHLIGHT A PRINT MEDIUM THAT PLAYED AN INFLUENTIAL ROLE IN THE DEVELOPMENT AND DISSEMINATION OF MODERN ART. OUR PRINT COLLECTION IS THE RICHEST AREA OF THE HWS COLLECTION, AND THIS EXHIBITION GIVES US THE OPPORTUNITY TO HIGHLIGHT SOME OF OUR MAJOR CONTRIBUTORS. ROBERT NORTH HAS BEEN ESPECIALLY GENER- OUS. IN THIS SMALL EXHIBITION ALONE, HE HAS DONATED, AMONG OTHERS, WORKS OF THE WELL-KNOWN ARTISTS ROMARE BEARDEN, GEORGE BELLOWS OF WHICH WE HAVE TWELVE, AND THOMAS HART BENTON – THE GREAT REGIONALIST ARTIST AND TEACHER OF JACKSON POLLOCK. -

Alberto Giacometti and the Crisis of the Monument, 1935–45 A

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Hollow Man: Alberto Giacometti and the Crisis of the Monument, 1935–45 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Art History by Joanna Marie Fiduccia 2017 Ó Copyright by Joanna Marie Fiduccia 2017 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Hollow Man: Alberto Giacometti and the Crisis of the Monument, 1935–45 by Joanna Marie Fiduccia Doctor of Philosophy in Art History University of California, Los Angeles, 2017 Professor George Thomas Baker, Chair This dissertation presents the first extended analysis of Alberto Giacometti’s sculpture between 1935 and 1945. In 1935, Giacometti renounced his abstract Surrealist objects and began producing portrait busts and miniature figures, many no larger than an almond. Although they are conventionally dismissed as symptoms of a personal crisis, these works unfold a series of significant interventions into the conventions of figurative sculpture whose consequences persisted in Giacometti’s iconic postwar work. Those interventions — disrupting the harmonious relationship of surface to interior, the stable scale relations between the work and its viewer, and the unity and integrity of the sculptural body — developed from Giacometti’s Surrealist experiments in which the production of a form paradoxically entailed its aggressive unmaking. By thus bridging Giacometti’s pre- and postwar oeuvres, this decade-long interval merges two ii distinct accounts of twentieth-century sculpture, each of which claims its own version of Giacometti: a Surrealist artist probing sculpture’s ambivalent relationship to the everyday object, and an Existentialist sculptor invested in phenomenological experience. This project theorizes Giacometti’s artistic crisis as the collision of these two models, concentrated in his modest portrait busts and tiny figures. -

PICASSO Les Livres D’Artiste E T Tis R a D’ S Vre Li S Le PICASSO

PICASSO LES LIVRES d’ARTISTE The collection of Mr. A*** collection ofThe Mr. d’artiste livres Les PICASSO PICASSO Les livres d’artiste The collection of Mr. A*** Author’s note Years ago, at the University of Washington, I had the opportunity to teach a class on the ”Late Picasso.” For a specialist in nineteenth-century art, this was a particularly exciting and daunting opportunity, and one that would prove formative to my thinking about art’s history. Picasso does not allow for temporalization the way many other artists do: his late works harken back to old masterpieces just as his early works are themselves masterpieces before their time, and the many years of his long career comprise a host of “periods” overlapping and quoting one another in a form of historico-cubist play that is particularly Picassian itself. Picasso’s ability to engage the art-historical canon in new and complex ways was in no small part influenced by his collaborative projects. It is thus with great joy that I return to the varied treasures that constitute the artist’s immense creative output, this time from the perspective of his livres d’artiste, works singularly able to point up his transcendence across time, media, and culture. It is a joy and a privilege to be able to work with such an incredible collection, and I am very grateful to Mr. A***, and to Umberto Pregliasco and Filippo Rotundo for the opportunity to contribute to this fascinating project. The writing of this catalogue is indebted to the work of Sebastian Goeppert, Herma Goeppert-Frank, and Patrick Cramer, whose Pablo Picasso. -

Annual Report 1995

19 9 5 ANNUAL REPORT 1995 Annual Report Copyright © 1996, Board of Trustees, Photographic credits: Details illustrated at section openings: National Gallery of Art. All rights p. 16: photo courtesy of PaceWildenstein p. 5: Alexander Archipenko, Woman Combing Her reserved. Works of art in the National Gallery of Art's collec- Hair, 1915, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, 1971.66.10 tions have been photographed by the department p. 7: Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo, Punchinello's This publication was produced by the of imaging and visual services. Other photographs Farewell to Venice, 1797/1804, Gift of Robert H. and Editors Office, National Gallery of Art, are by: Robert Shelley (pp. 12, 26, 27, 34, 37), Clarice Smith, 1979.76.4 Editor-in-chief, Frances P. Smyth Philip Charles (p. 30), Andrew Krieger (pp. 33, 59, p. 9: Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon in His Study, Editors, Tarn L. Curry, Julie Warnement 107), and William D. Wilson (p. 64). 1812, Samuel H. Kress Collection, 1961.9.15 Editorial assistance, Mariah Seagle Cover: Paul Cezanne, Boy in a Red Waistcoat (detail), p. 13: Giovanni Paolo Pannini, The Interior of the 1888-1890, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon Pantheon, c. 1740, Samuel H. Kress Collection, Designed by Susan Lehmann, in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National 1939.1.24 Washington, DC Gallery of Art, 1995.47.5 p. 53: Jacob Jordaens, Design for a Wall Decoration (recto), 1640-1645, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, Printed by Schneidereith & Sons, Title page: Jean Dubuffet, Le temps presse (Time Is 1875.13.1.a Baltimore, Maryland Running Out), 1950, The Stephen Hahn Family p. -

Networking Surrealism in the USA. Agents, Artists and the Market

151 Toward a New “Human Consciousness”: The Exhibition “Adventures in Surrealist Painting During the Last Four Years” at the New School for Social Research in New York, March 1941 Caterina Caputo On January 6, 1941, the New School for Social Research Bulletin announced a series of forthcoming surrealist exhibitions and lectures (fig. 68): “Surrealist Painting: An Adventure into Human Consciousness; 4 sessions, alternate Wednesdays. Far more than other modern artists, the Surrea- lists have adventured in tapping the unconscious psychic world. The aim of these lectures is to follow their work as a psychological baro- meter registering the desire and impulses of the community. In a series of exhibitions contemporaneous with the lectures, recently imported original paintings are shown and discussed with a view to discovering underlying ideas and impulses. Drawings on the blackboard are also used, and covered slides of work unavailable for exhibition.”1 From January 22 to March 19, on the third floor of the New School for Social Research at 66 West Twelfth Street in New York City, six exhibitions were held presenting a total of thirty-six surrealist paintings, most of which had been recently brought over from Europe by the British surrealist painter Gordon Onslow Ford,2 who accompanied the shows with four lectures.3 The surrealist events, arranged by surrealists themselves with the help of the New School for Social Research, had 1 New School for Social Research Bulletin, no. 6 (1941), unpaginated. 2 For additional biographical details related to Gordon Onslow Ford, see Harvey L. Jones, ed., Gordon Onslow Ford: Retrospective Exhibition, exh.