The Road Goes Ever On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mythlore Index Plus

MYTHLORE INDEX PLUS MYTHLORE ISSUES 1–137 with Tolkien Journal Mythcon Conference Proceedings Mythopoeic Press Publications Compiled by Janet Brennan Croft and Edith Crowe 2020. This work, exclusive of the illustrations, is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/us/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. Tim Kirk’s illustrations are reproduced from early issues of Mythlore with his kind permission. Sarah Beach’s illustrations are reproduced from early issues of Mythlore with her kind permission. Copyright Sarah L. Beach 2007. MYTHLORE INDEX PLUS An Index to Selected Publications of The Mythopoeic Society MYTHLORE, ISSUES 1–137 TOLKIEN JOURNAL, ISSUES 1–18 MYTHOPOEIC PRESS PUBLICATIONS AND MYTHCON CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS COMPILED BY JANET BRENNAN CROFT AND EDITH CROWE Mythlore, January 1969 through Fall/Winter 2020, Issues 1–137, Volume 1.1 through 39.1 Tolkien Journal, Spring 1965 through 1976, Issues 1–18, Volume 1.1 through 5.4 Chad Walsh Reviews C.S. Lewis, The Masques of Amen House, Sayers on Holmes, The Pedant and the Shuffly, Tolkien on Film, The Travelling Rug, Past Watchful Dragons, The Intersection of Fantasy and Native America, Perilous and Fair, and Baptism of Fire Narnia Conference; Mythcon I, II, III, XVI, XXIII, and XXIX Table of Contents INTRODUCTION Janet Brennan Croft .....................................................................................................................................1 -

Article Fairy Marriages in Tolkien’S Works GIOVANNI C

article Fairy marriages in Tolkien’s works GIOVANNI C. COSTABILE Both in its Celtic and non-Celtic declinations, the motif the daughter of the King of Faerie, who bestows on him a of the fairy mistress has an ancient tradition stretching magical source of wealth, and will visit him whenever he throughout different areas, ages, genres, media and cul- wants, so long as he never tells anybody about her.5 Going tures. Tolkien was always fascinated by the motif, and used further back, the nymph Calypso, who keeps Odysseus on it throughout his works, conceiving the romances of Beren her island Ogygia on an attempt to make him her immortal and Lúthien, and Aragorn and Arwen. In this article I wish husband,6 can be taken as a further (and older) version of to point out some minor expressions of the same motif in the same motif. Tolkien’s major works, as well as to reflect on some over- But more pertinent is the idea of someone’s ancestor being looked aspects in the stories of those couples, in the light of considered as having married a fairy. Here we can turn to the often neglected influence of Celtic and romance cultures the legend of Sir Gawain, as Jessie Weston and John R. Hul- on Tolkien. The reader should also be aware that I am going bert interpret Gawain’s story in Sir Gawain and the Green to reference much outdated scholarship, that being my pre- Knight as a late, Christianised version of what once was a cise intent, though, at least since this sort of background fairy-mistress tale in which the hero had to prove his worth may conveniently help us in better understanding Tolkien’s through the undertaking of the Beheading Test in order to reading of both his theoretical and actual sources. -

MASTER BOOK 3+3 NEW 6/10/07 2:58 PM Page 2

120860bk Joyce:MASTER BOOK 3+3 NEW 6/10/07 2:58 PM Page 2 1. I’m Going To See You Today 2:16 7. Mad About The Boy 5:08 12. The Music’s Message 3:05 16. Folk Song (A Song Of The Weather) (Joyce Grenfell–Richard Addinsell) (Noël Coward) (Joyce Grenfell–Richard Addinsell) 1:29 With Richard Addinsell, piano With Mantovani & His Orchestra; Orchestra conducted by William Blezard (Michael Flanders-Donald Swann) HMV B 9295, 0EA 9899-5 introduced by Noël Coward 13. Understanding Mother 3:10 With piano Recorded 17 September 1942 Noël Coward Programme #4, (Joyce Grenfell) 17. Shirley’s Girl Friend 4:46 Towers of London, 1947–48 2. There Is Nothing New To Tell You 3:29 14. Three Brothers 2:57 (Joyce Grenfell) (Joyce Grenfell–Richard Addinsell) 8. Children Of The Ritz 3:59 (Joyce Grenfell–Richard Addinsell) 18. Hostess; Farewell 3:03 With Richard Addinsell, piano (Noël Coward) Orchestra conducted by William Blezard (Joyce Grenfell–Richard Addinsell) HMV B 9295, 0EA 9900-1 With Mantovani & His Orchestra Orchestra conducted by William Blezard Recorded 3 September 1942 Noël Coward Programme #12, 15. Palais Dancers 3:13 Towers of London, 1947–48 (Joyce Grenfell–Richard Addinsell) Tracks 12–18 from 3. Useful And Acceptable Gifts Orchestra conducted by William Blezard Joyce Grenfell Requests the Pleasure (An Institute Lecture Demonstration) 3:05 9. We Must All Be Very Kind To Auntie Philips BBL 7004; recorded 1954 From The Little Revue Jessie 3:28 (Joyce Grenfell) (Noël Coward) All selections recorded in London • Tracks 5–9 previously unissued commercially HMV B 8930, 0EA 7852-1 With Mantovani & His Orchestra Transfers and Production: David Lennick • Digital Restoration:Alan Bunting Recorded 11 May 1939 (3:04) Noël Coward Programme #13, Original records from the collections of David Lennick and CBC Radio, Toronto 4. -

Birmingham Science Fiction Group Newsletter

(Honorary Presidents: Brian W. Aldiss Birmingham and Harry Harrison) Science Fiction Group NEWSLETTER 139 MARCH 1983 The Birmingham Science Fiction Group has its formal meeting on the third Friday of each month in the upstairs room of the IVY BUSH pub on the cor ner of Hagley Road and Monument Road, Edgbaston, Birmingham 16. There is also an informal meeting on the first Tuesday of each month at THE OLD ROYAL pub, on the corner of Church Street and Cornwall Street, Birmingham 3, (Church Street is off Colmore Row.) New members are always welcome. Our treasurer is Margaret Thorpe, 36 Twyford Road, Ward End, Birmingham 8. The 12-months subscription is £3.50. MARCH MEETING - Friday 18th March at 7.45 pm. "Through Time and Space With " Pete Weston will lead a discussion (with slides) exploring SF, past, present and future. He would like this meeting to be one of active participation by the members, putting forward their views about authors and SF. Afterwards, interested members are invited to go for a late night meal together. Admission this month: members 30p, non-members 60p. FEBRUARY MEETING John Sladek is an entertaining writer who read us a hilarious short story full of black humour. He answered questions about his career and revealed that he prefers his books to be published first in paperback so that they reach the readership instead of collecting dust on library shelves, as he feels his duty is to entertain. Afterwards by Dean Bisseker. Those of you who did not come missed a great rounding off to the evening. -

The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence Upon J. R. R. Tolkien

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 12-2007 The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence upon J. R. R. Tolkien Kelvin Lee Massey University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Massey, Kelvin Lee, "The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence upon J. R. R. olkien.T " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2007. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/238 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Kelvin Lee Massey entitled "The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence upon J. R. R. olkien.T " I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in English. David F. Goslee, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Thomas Heffernan, Michael Lofaro, Robert Bast Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Kelvin Lee Massey entitled “The Roots of Middle-earth: William Morris’s Influence upon J. -

Guide to Tolkienian Nationality Words by Malinornë After an Idea by ~Nóleme~

Guide to Tolkienian nationality words By Malinornë after an idea by ~nóleme~ The purpose of this chart is to help writers of fan fiction to avoid common mistakes involving non-English names for groups and individuals of various peoples, languages etc. The letters in parenthesis in the first column show which language the main term is in: Q for Quenya, S for Sindarin, E for English, D for Dwarvish and R for Rohirric. For many of the Sindarin terms, two plural forms are listed. The term marked "coll." is a collective noun or class plural that is used for a people or group as a whole. If you need a term for a number of individuals, then use the second one listed. Example: "the two Enyd", not "the two Onodrim". Or, make it simple and use English: "the two Ents" :) If the general adjective is not known, it usually works to circumscribe, e.g. write "of the Dúnedain". It can also work to simply use a noun, e.g. "She had hobbit blood." Avoid the plural form – don't write "He had Eorlingas ancestors." People or group Individual General adjective Language(s) spoken (plural or collective noun) (singular noun) by people or group Ainur (Q) Ainu (fem. Aini) Ainurin Valarin, Quenya Atani (Q) Atan - - Apanónar (Q) - - Ebennin (S) Abonnen (S) Avari (Q) Avar (Q + S) Avarin (Q) Avarin Evair (S) Balroeg (S) Balrog (S) - - Valaraukar (Q) Valarauko (Q) Calaquendi (Q) Calaquendë (Q) Calaquenderin (Q) Quenya, Sindarin, other Celbin (S) Calben (S) Drúedain (Q), Drûgs (E) Drúadan, Drûg - - Dúnedain (S) Dúnadan - Westron, Sindarin Dúnedhil (S) Dúnedhel Dúnedhellen Quenya, Sindarin, other Edain (S) Adan - - Eglath, Egladhrim (S, coll.) Eglan - - Eglain (S) Eldar (Q) Elda (Q) Eldarin (Q) Eldarin, Quenya, Sindarin Edhil (S) Edhel (S) Edhellen (S) Eorlingas (R), Eorlings (E) Eorling - Rohirric Eruhíni (Q) Eruhína (Q) - - Eruchín (S) Eruchen (S) Falathrim (S, coll.) Falathel ?Falathren Sindarin Felethil (S) (lit. -

Croydon Friends Newsletter

CROYDON FRIENDS NEWSLETTER January 2016 Dear Friends, Our newsletter this month gathers together news of Friends sent in on Christmas cards or in letters and emails, which reflect our Meeting as a family community It also reflects our lives within the Quaker world, within our community, our Area Meeting, and our Religious Society as a whole. Gillian Turner “My grace is sufficient for thee”, 2 Corinthians 12:9 At this time of year, we are encouraged to believe that in order to achieve happiness and peace we should draw up a list of New Year’s Resolutions. As if by magic we will become fitter and stronger, more intelligent, give up a creeping sugar addiction, be much nicer and more helpful to Ffriends and family etc. Each year I find the list easier and easier to compile as one “benefit” of the ageing process seems to be a heightened awareness of my shortcomings. When designing advertising campaigns, the toxic bombs of guilt and shame are sometimes used in order to encourage our mostly fruitless attempts at so-called self-improvement. Businesses know that resolutions made at this time of year invariably lead to the need to buy goods and services which purport to help us to achieve our targets. Exercise bikes, subscriptions to improving publications, gym memberships and cosmetics are often marketed as the means to realise our dreams. Of course, thinking about a few, well-chosen, specific and achievable ideas by which to either increase self-esteem and/or help our fellows is no bad thing and can be done at any time of the year, without the purchase of items which will end up in the back of a cupboard or drawer. -

German Operetta on Broadway and in the West End, 1900–1940

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.58, on 26 Sep 2021 at 08:28:39, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/2CC6B5497775D1B3DC60C36C9801E6B4 Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.58, on 26 Sep 2021 at 08:28:39, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/2CC6B5497775D1B3DC60C36C9801E6B4 German Operetta on Broadway and in the West End, 1900–1940 Academic attention has focused on America’sinfluence on European stage works, and yet dozens of operettas from Austria and Germany were produced on Broadway and in the West End, and their impact on the musical life of the early twentieth century is undeniable. In this ground-breaking book, Derek B. Scott examines the cultural transfer of operetta from the German stage to Britain and the USA and offers a historical and critical survey of these operettas and their music. In the period 1900–1940, over sixty operettas were produced in the West End, and over seventy on Broadway. A study of these stage works is important for the light they shine on a variety of social topics of the period – from modernity and gender relations to new technology and new media – and these are investigated in the individual chapters. This book is also available as Open Access on Cambridge Core at doi.org/10.1017/9781108614306. derek b. scott is Professor of Critical Musicology at the University of Leeds. -

Disability and Music

th nd 19 November to 22 December UKDHM 2018 will focus on Disability and Music. We want to explore the links between the experience of disablement in a world where the barriers faced by people with impairments can be overwhelming. Yet the creative impulse, urge for self expression and the need to connect to our fellow human beings often ‘trumps’ the oppression we as disabled people have faced, do face and will face in the future. Each culture and sub-culture creates identity and defines itself by its music. ‘Music is the language of the soul. To express ourselves we have to be vibrating, radiating human beings!’ Alasdair Fraser. Born in Salford in 1952, polio survivor Alan Holdsworth goes by the stage name ‘Johnny Crescendo’. His music addresses civil rights, disability pride and social injustices, making him a crucial voice of the movement and one of the best-loved performers on the disability arts circuit. In 1990 and 1992, Alan co- organised Block Telethon, a high-profile media and community campaign which culminated in the demise of the televised fundraiser. His albums included Easy Money, Pride and Not Dead Yet, all of which celebrate disabled identity and critique disabling barriers and attitudes. He is best known for his song Choices and Rights, which became the anthem for the disabled people’s movement in Britain in the late 1980s and includes the powerful lyrics: Choices and Right That’s what we gotta fight for Choices and rights in our lives I don’t want your benefit I want dignity from where I sit I want choices and rights in our lives I don’t want you to speak for me I got my own autonomy I want choices and rights in our lives https://youtu.be/yU8344cQy5g?t=14 The polio virus attacked the nerves. -

Clashing Perspectives of World Order in JRR Tolkien's Middle-Earth

ABSTRACT Fate, Providence, and Free Will: Clashing Perspectives of World Order in J. R. R. Tolkien’s Middle-earth Helen Theresa Lasseter Mentor: Ralph C. Wood, Ph.D. Through the medium of a fictional world, Tolkien returns his modern audience to the ancient yet extremely relevant conflict between fate, providence, and the person’s freedom before them. Tolkien’s expression of a providential world order to Middle-earth incorporates the Northern Germanic cultures’ literary depiction of a fated world, while also reflecting the Anglo-Saxon poets’ insight that a single concept, wyrd, could signify both fate and providence. This dissertation asserts that Tolkien, while acknowledging as correct the Northern Germanic conception of humanity’s final powerlessness before the greater strength of wyrd as fate, uses the person’s ultimate weakness before wyrd as the means for the vindication of providence. Tolkien’s unique presentation of world order pays tribute to the pagan view of fate while transforming it into a Catholic understanding of providence. The first section of the dissertation shows how the conflict between fate and providence in The Silmarillion results from the elvish narrator’s perspective on temporal events. Chapter One examines the friction between fate and free will within The Silmarillion and within Tolkien’s Northern sources, specifically the Norse Eddas, the Anglo-Saxon Beowulf, and the Finnish The Kalevala. Chapter Two shows that Tolkien, following Boethius’s Consolation of Philosophy, presents Middle-earth’s providential order as including fated elements but still allowing for human freedom. The second section shows how The Lord of the Rings reflects but resolves the conflict in The Silmarillion between fate, providence, and free will. -

SINDARIN 2003 (MMDCCLVI AVC) R [email protected] Gandalf

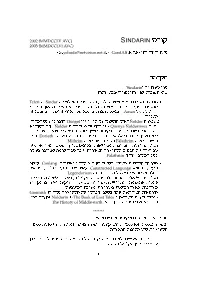

2002 (MMDCCLV AVC) SINDARIN 2003 (MMDCCLVI AVC) r [email protected] GandAlf Sindarin Teleri Sindar Aman Thingol Noldor˜ Noldor˜ Quenya Noldorinwa˜ Doriath Mithrim Falathrim Falathrim Conlang Constructed Language Legendarivm Gnomish Noldorin The Book of Lost Tales The History of Middle-earth ******* At Mereth Aderthad many counsels were taken in good will, and oaths were sworn of league and friendship; and it is told that at this feast the tongue of the Grey-elves was most spoken even by the Noldor, for they learned swiftly the speech of Beleriand, whereas the Sindar were slow to master the tongue of Valinor. (The Silmarillion, ch. 13) Quenya Noldorinwa˜ Noldor˜ Beleriand Noldor˜ ******* Helge Kar˚ e Fauskanger Quenya http://www.ardalambion.com/qcourse.html Suomi Finnish Aman Quendi Kvener Noldor˜ http://www.sci.fi/˜alboin/finn_que.htm http://demo.ort.org.il/ortforums/scripts/ forum.asp?pc=471389549 ******* Ardalambion http://www.ardalambion.com/sindarin.html Gwaith-i-Phethdain http://www.elvish.org/gwaith/sindarin_intro.htm Ardalambion ******* Didier Willis Ryszard Derdzinski Willis mirror http://forums.ort.org.il/scripts/showsm.asp?which_ forum=18&mess=1042485 ELF Vinyar Tengwar http://www.elvish.org/VT Derdzinski http://www.uib.no/People/hnohf/gobeth.htm Willis http://www.geocities.com/almacq.geo/sindar http://my.ort.org.il/tolkien/gandalf2/sindarin.zip ******* Grimm’s Law :-) ******* Gnomish Arda Noldorin http://www.elvish.org E.L.F. :-( ******* Mircosoft Word LYX TEX/LATEX Word www.lyx.org www.latex-project.org www.tug.org LATEX -

THE CIRTH the Certhas Daeron Was Originallypb Devisedmt Tod Representnk Theg Soundsnr of Sindarinls Only

THE CIRTH The Certhas Daeron was originallypb devisedmt tod representnk theg soundsNr of SindarinlS only. The oldest cirth were , , , ; , , ; , , ; , ; , ziueo 1 2 5 6 8 9 12¤ 18 ¥19 22 29 31 35 ; , , , ; and a certh varying between and . The assignment 36 39 42 46 50 iue o 13 15 of values was unsystematic. , , and were vowels and remained so ¤ 39 42 ¥ 46 50 S in all later developments. 13 and 15 were used for h or s, according as 35 was used for s or h. This tendency to hesitate in the assignment of values for s and h continued in laterpl arangements. In those characters that consisted of a ‘stem’ and a ‘branch’, 1 – 31 , the attachment of the branch was, if on one side only, usually made on the right side. The reverse was not infrequent, but had no phonetic significance. The extension and elaboration of this certhas was called in its older form the Angerthas Daeron, since the additions to the old cirth and their re-organization was attributed to¤ Daeron.§ The principal additions, however, the introductions of two new series, 13 – 17 , and 23 – 28 , were actually most probably inventions of the Noldor of Eregion, since they were used for the representation of sounds not found in Sindarin. In the rearrangement of the Angerthas the following principles are observable (evidently inspired by the F¨eanorian system): (1) adding a stroke to a brance added a ‘voice’; (2) reversing the certh indicated opening to a ‘spirant’; (3) placing the branch on both sides of the stem added voice and nasality.