Birth of a Play: the Documentation of a Process an Interview with G. P Deshpande Earlier This Year the Well-Known Marathi Playwr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Young India Young in Gold’ Is ‘Old

downloaded from : www.visionias.net downloaded from : https://t.me/Material_For_Exam follow us: friday, february 2, 2018 Delhi City Edition thehindu.com 36 pages ț 10.00 facebook.com/thehindu twitter.com/the_hindu Printed at . Chennai . Coimbatore . Bengaluru . Hyderabad . Madurai . Noida . Visakhapatnam . Thiruvananthapuram . Kochi . Vijayawada . Mangaluru . Tiruchirapalli . Kolkata . Hubballi . Mohali . Malappuram . Mumbai . Tirupati . lucknow In a preelection Budget, Finance Minister Arun Jaitley serves up a mix of populism and prudence FARMER SUTRA Special Correspondent <> The focus of the litre has been levied to fund NEW DELHI Budget is farmers, projects. Unlike excise du With a clear eye on the Lok rural India, ties, the Centre is not re Sabha election, Union Fi healthcare and quired to share cess receipts nance Minister Arun Jaitley with the States. education pulled out all the stops in The government’s inabili Arun Jaitley the Narendra Modi govern Finance Minister ty to give away too many ment’s last full Budget to goodies were largely due to promise a better deal for show that individual busi its scal constraints, with farmers, boost the rural nesspersons paid less aver this year’s scal decit over economy and make the age tax than the salaried shooting the 3.2% of GDP poor less vulnerable to class, he reintroduced a at target and likely to touch health exigencies. 40,000 deduction from 3.5% on account of the GST Responding to the dis taxable income for the latter related issues. Instead of a tress in the agriculture in lieu of the existing tax ex 3% decit in the coming sector that has reared its emptions for transport and year, the Centre settled to head in various States medical allowance and ex target the 3.3% mark, defer over the past year, the tended this relief to pen ring the glide path to 3% to government has decid sioners. -

List of Empanelled Artist

INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMENT ARTISTS S.No. Name of Artist/Group State Date of Genre Contact Details Year of Current Last Cooling off Social Media Presence Birth Empanelment Category/ Sponsorsred Over Level by ICCR Yes/No 1 Ananda Shankar Jayant Telangana 27-09-1961 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-40-23548384 2007 Outstanding Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vwH8YJH4iVY Cell: +91-9848016039 September 2004- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vrts4yX0NOQ [email protected] San Jose, Panama, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YDwKHb4F4tk [email protected] Tegucigalpa, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SIh4lOqFa7o Guatemala City, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MiOhl5brqYc Quito & Argentina https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COv7medCkW8 2 Bali Vyjayantimala Tamilnadu 13-08-1936 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44-24993433 Outstanding No Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wbT7vkbpkx4 +91-44-24992667 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zKvILzX5mX4 [email protected] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kyQAisJKlVs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q6S7GLiZtYQ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WBPKiWdEtHI 3 Sucheta Bhide Maharashtra 06-12-1948 Bharatanatyam Cell: +91-8605953615 Outstanding 24 June – 18 July, Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WTj_D-q-oGM suchetachapekar@hotmail 2015 Brazil (TG) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UOhzx_npilY .com https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SgXsRIOFIQ0 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lSepFLNVelI 4 C.V.Chandershekar Tamilnadu 12-05-1935 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44- 24522797 1998 Outstanding 13 – 17 July 2017- No https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ec4OrzIwnWQ -

Sankeet Natak Akademy Awards from 1952 to 2016

All Sankeet Natak Akademy Awards from 1952 to 2016 Yea Sub Artist Name Field Category r Category Prabhakar Karekar - 201 Music Hindustani Vocal Akademi 6 Awardee Padma Talwalkar - 201 Music Hindustani Vocal Akademi 6 Awardee Koushik Aithal - 201 Music Hindustani Vocal Yuva Puraskar 6 Yashasvi 201 Sirpotkar - Yuva Music Hindustani Vocal 6 Puraskar Arvind Mulgaonkar - 201 Music Hindustani Tabla Akademi 6 Awardee Yashwant 201 Vaishnav - Yuva Music Hindustani Tabla 6 Puraskar Arvind Parikh - 201 Music Hindustani Sitar Akademi Fellow 6 Abir hussain - 201 Music Hindustani Sarod Yuva Puraskar 6 Kala Ramnath - 201 Akademi Music Hindustani Violin 6 Awardee R. Vedavalli - 201 Music Carnatic Vocal Akademi Fellow 6 K. Omanakutty - 201 Akademi Music Carnatic Vocal 6 Awardee Neela Ramgopal - 201 Akademi Music Carnatic Vocal 6 Awardee Srikrishna Mohan & Ram Mohan 201 (Joint Award) Music Carnatic Vocal 6 (Trichur Brothers) - Yuva Puraskar Ashwin Anand - 201 Music Carnatic Veena Yuva Puraskar 6 Mysore M Manjunath - 201 Music Carnatic Violin Akademi 6 Awardee J. Vaidyanathan - 201 Akademi Music Carnatic Mridangam 6 Awardee Sai Giridhar - 201 Akademi Music Carnatic Mridangam 6 Awardee B Shree Sundar 201 Kumar - Yuva Music Carnatic Kanjeera 6 Puraskar Ningthoujam Nata Shyamchand 201 Other Major Music Sankirtana Singh - Akademi 6 Traditions of Music of Manipur Awardee Ahmed Hussain & Mohd. Hussain (Joint Award) 201 Other Major Sugam (Hussain Music 6 Traditions of Music Sangeet Brothers) - Akademi Awardee Ratnamala Prakash - 201 Other Major Sugam Music Akademi -

Indian Council for Cultural Relations Empanelment Artists

INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMENT ARTISTS S.No. Name of Artist/Group State Date of Genre Contact Details Year of Current Sponsored by Occasion Social Media Presence Birth Empanel Category/ ICCR including Level Travel Grants 1 Ananda Shankar Jayant Telangana 9/27/1961 Bharatanatyam C-52, Road No.10, 2007 Outstanding 1997-South Korea To give cultural https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vwH8YJH4iVY Film Nagar, Jubilee Hills Myanmar Vietnam Laos performances to https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vrts4yX0NOQ Hyderabad-500096 Combodia, coincide with the https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YDwKHb4F4tk Cell: +91-9848016039 2002-South Africa, Establishment of an https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SIh4lOqFa7o +91-40-23548384 Mauritius, Zambia & India – Central https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MiOhl5brqYc [email protected] Kenya American Business https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COv7medCkW8 [email protected] 2004-San Jose, Forum in Panana https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kSr8A4H7VLc Panama, Tegucigalpa, and to give cultural https://www.ted.com/talks/ananda_shankar_jayant_fighti Guatemala City, Quito & performances in ng_cancer_with_dance Argentina other countries https://www.youtube.com/user/anandajayant https://www.youtube.com/user/anandasj 2 Bali Vyjayantimala Tamilnadu 8/13/1936 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44-24993433 Outstanding No https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wbT7vkbpkx4 +91-44-24992667 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zKvILzX5mX4 [email protected] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kyQAisJKlVs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q6S7GLiZtYQ -

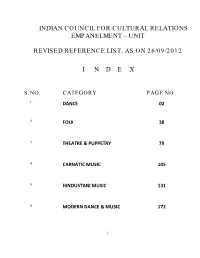

Unit Revised Reference List, As on 26/09/2012 I

INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMENT – UNIT REVISED REFERENCE LIST, AS ON 26/09/2012 I N D E X S.NO. CATEGORY PAGE NO 1. DANCE 02 2. FOLK 38 3. THEATRE & PUPPETRY 79 4. CARNATIC MUSIC 105 5. HINDUSTANI MUSIC 131 6. MODERN DANCE & MUSIC 172 1 INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMEMT SECTION REVISED REFERENCE LIST FOR DANCE - AS ON 26/09/2012 S.NO. CATEGORY PAGE NO 1. BHARATANATYAM 3 – 11 2. CHHAU 12 – 13 3. KATHAK 14 – 19 4. KATHAKALI 20 – 21 5. KRISHNANATTAM 22 6. KUCHIPUDI 23 – 25 7. KUDIYATTAM 26 8. MANIPURI 27 – 28 9. MOHINIATTAM 29 – 30 10. ODISSI 31 – 35 11. SATTRIYA 36 12. YAKSHAGANA 37 2 REVISED REFERENCE LIST FOR DANCE AS ON 26/09/2012 BHARATANATYAM OUTSTANDING 1. Ananda Shankar Jayant (Also Kuchipudi) (Up) 2007 2. Bali Vyjayantimala 3. Bhide Sucheta 4. Chandershekar C.V. 03.05.1998 5. Chandran Geeta (NCR) 28.10.1994 (Up) August 2005 6. Devi Rita 7. Dhananjayan V.P. & Shanta 8. Eshwar Jayalakshmi (Up) 28.10.1994 9. Govind (Gopalan) Priyadarshini 03.05.1998 10. Kamala (Migrated) 11. Krishnamurthy Yamini 12. Malini Hema 13. Mansingh Sonal (Also Odissi) 14. Narasimhachari & Vasanthalakshmi 03.05.1998 15. Narayanan Kalanidhi 16. Pratibha Prahlad (Approved by D.G March 2004) Bangaluru 17. Raghupathy Sudharani 18. Samson Leela 19. Sarabhai Mallika (Up) 28.10.1994 20. Sarabhai Mrinalini 21. Saroja M K 22. Sarukkai Malavika 23. Sathyanarayanan Urmila (Chennai) 28.10.94 (Up)3.05.1998 24. Sehgal Kiran (Also Odissi) 25. Srinivasan Kanaka 26. Subramanyam Padma 27. -

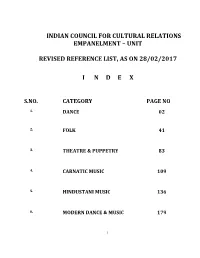

Unit Revised Reference List, As on 28/02/2017 I

INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMENT – UNIT REVISED REFERENCE LIST, AS ON 28/02/2017 I N D E X S.NO. CATEGORY PAGE NO 1. DANCE 02 2. FOLK 41 3. THEATRE & PUPPETRY 83 4. CARNATIC MUSIC 109 5. HINDUSTANI MUSIC 136 6. MODERN DANCE & MUSIC 179 1 INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMEMT SECTION REVISED REFERENCE LIST FOR DANCE - AS ON 28/02/2017 S.NO. CATEGORY PAGE NO 1. BHARATANATYAM 3 – 11 2. CHHAU 12 – 13 3. KATHAK 14 – 20 4. KATHAKALI 21 – 22 5. KRISHNANATTAM 23 6. KUCHIPUDI 24 – 26 7. KUDIYATTAM 27 8. OTTAN THULLAL 28 9. MANIPURI 29 – 30 10. MOHINIATTAM 31– 32 11. ODISSI 33 – 37 12. SATTRIYA 38-39 13. YAKSHAGANA 40 2 REVISED REFERENCE LIST FOR DANCE AS ON 28/02/2017 BHARATANATYAM OUTSTANDING 1. Ananda Shankar Jayant (Also Kuchipudi) (Up) 2007 2. Bali Vyjayantimala 3. Bhide Sucheta 4. Chandershekar C.V. 03.05.1998 5. Chandran Geeta (NCR) 28.10.1994 (Up) August 2005 6. Devi Rita 7. Dhananjayan V.P. & Shanta 8. Eshwar Jayalakshmi (Up) 28.10.1994 9. Govind (Gopalan) Priyadarshini 03.05.1998 10. Kamala (Migrated) 11. Krishnamurthy Yamini 12. Malini Hema 13. Mansingh Sonal (Also Odissi) 14. Narasimhachari & Vasanthalakshmi 03.05.1998 15. Narthaki Nataraj (Chennai) 2007 (Up)2017 16. Pratibha Prahlad (Approved by D.G March 2004) Bangaluru 17. Raghupathy Sudharani 18. Samson Leela 19. Sarabhai Mallika (Up) 28.10.1994 20. Saroja M K 21. Sarukkai Malavika 22. Sathyanarayanan Urmila (Chennai) 28.10.94 (Up)3.05.1998 23. Sehgal Kiran (Also Odissi) 24. -

Balraj Sahni an Autobiography

Balraj Sahni an autobiography A revealing intimate and delightful story of the life of a great actor. An insight into his life and into the world of films—the glamour, the romance, the secret lives and secret deals laid bare, as never before. A highly sensitive and brutally frank inside account of the world of the film industry. The uneasy road to stardom, the torture and the glory of success and fame.. This is Balraj Sahni by Balraj Sahni, the man adored by millions. Flash-back is an accepted technique of film-making. Unless, however, the viewers have first been made sufficiently familiar with the events that happen in the ‘present’ of the film, no flash-back is going to produce the desired effect on them. I, therefore, invite you to share same of my ‘present’ before I start unfolding before you the flash-back of my screen life. Come along then, I shall take you to a make-up room in one of the studios at Chembur. True to convention and tradition, the make-up man has applied a tilak to the mirror, before getting to work on my face. He has now finished his job. I look at myself in the mirror and notice that the ‘silver’ of my hair is showing rather prominently. Oh, yes, I have not used the khizab (dye) for several weeks now! I hastily pick, a dye pencil from the table in front of me and start vigorously drawing it across my temples. There, that’s better! While I was banishing my grey hair, the dressman called at my room to deliver my military uniform and boots, polished to perfection. -

Indian Council for Cultural Relations Empanelment of Artistes

INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMENT OF ARTISTES REVISED REFERENCE LIST AS ON 26/09/2012 I N D E X S.NO. CATEGORY PAGE NO 1. DANCE 02 2. FOLK 38 3. THEATRE & PUPPETRY 79 4. CARNATIC MUSIC 105 5. HINDUSTANI MUSIC 131 6. MODERN DANCE & MUSIC 172 1 INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMEMT SECTION REVISED REFERENCE LIST FOR DANCE - AS ON 26/09/2012 S.NO. CATEGORY PAGE NO 1. BHARATANATYAM 3 – 11 2. CHHAU 12 – 13 3. KATHAK 14 – 19 4. KATHAKALI 20 – 21 5. KRISHNANATTAM 22 6. KUCHIPUDI 23 – 25 7. KUDIYATTAM 26 8. MANIPURI 27 – 28 9. MOHINIATTAM 29 – 30 10. ODISSI 31 – 35 11. SATTRIYA 36 12. YAKSHAGANA 37 2 REVISED REFERENCE LIST FOR DANCE AS ON 26/09/2012 BHARATANATYAM OUTSTANDING 1. Ananda Shankar Jayant (Also Kuchipudi) 2. Bali Vyjayantimala 3. Bhide Sucheta 4. Chandershekar C.V. 5. Chandran Geeta (NCR) 6. Devi Rita 7. Dhananjayan V.P. & Shanta 8. Eshwar Jayalakshmi 9. Govind (Gopalan) Priyadarshini 10. Kamala (Migrated) 11. Krishnamurthy Yamini 12. Malini Hema 13. Mansingh Sonal (Also Odissi) 14. Narasimhachari & Vasanthalakshmi 15. Narayanan Kalanidhi 16. Pratibha Prahlad (Approved by D.G March 2004) Bangaluru 17. Raghupathy Sudharani 18. Samson Leela 19. Sarabhai Mallika 20. Sarabhai Mrinalini 21. Saroja M K 22. Sarukkai Malavika 23. Sathyanarayanan Urmila (Chennai) 24. Sehgal Kiran (Also Odissi) 25. Srinivasan Kanaka 26. Subramanyam Padma 27. Vaidyanathan Rama (NCR) 28. Valli Alarmel (Spe.) 29. Viswanathan Lakshmi 30. Visweswaran Chitra 3 BHARATANATYAM ESTABLISHED 1. Anjana Anand (Chennai) 2. Ashok Purnima (Bangaluru) 3. Arekar Vaibhav S. (Mumbai) 4. Balasubramaniam Ramesh Uma (Chennai) 5. -

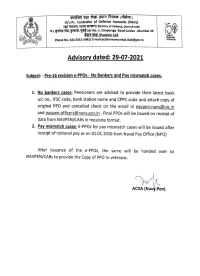

Advisory Dated: 29-07-2021

o/o Pr. Controller of Defence Accounts (Navy) TaT HATET, 4A ¥YOR/ Ministry of Defence, Govt of India 1 s,FIT, TT-39/ No.-1, Cooperage Road Colaba, Mumbai-39 TEAS OF TRTH /Pension Cell CELEBRATNG ARTMENS Phone No. 022-2551-5942/ [email protected] THE NAHATMA Advisory dated: 29-07-2021 Subject: Pre-16 revision e-PPO$ - No Bankersand Pay mismatch cases, 1. No bankers cases- Pensioners are advised to provide their latest bank a/c no., FSC code, bank station name and CPPC code and attach copy of original PPO and cancelled check on the email id [email protected] and [email protected]. Final PPOs will be issued on receipt of data from NAVPEN/CABs in requisite format. 2. Pay mismatch cases- E-PPOs for pay mismatch cases will be issued after receipt of notional pay as on 01.01.2016 from Naval Pay Office (NPO) After issuance of the e-PPOs, the same will be handed over to NAVPEN/CABs to provide the Copy of PPO to veterans. ACDA (Navy-Pen) Sailors No Bank Sailor retired 2006-15 rank regNo name PO 123831K VISWANATH PALIVELA PO 176625Y C P ANDREW CPO 193419R RAJESH KUMAR SINGH PO 127011N SRIKANTH KOLLIPARA CPO 146594W SATHYANARAYANA VS LS 151792H KUBER NATH SINGH CPO 146623K CHOKKAKULA SATYA RAO MCPO-I 197655T DEEPAK MANDAVGADE CPO 160055N DEBESH CHANDRA PAUL PO 163378R DILIP SINGH LS 178217R MANOJ KUMAR SINGH PO 172498T PRAVEEN KUMAR KV CPO 198270R BINAY BHATTACHARJEE PO 176817H AKHILESH KUMAR PO 176640F BENNY P GEORGE CPO 193396N NEERAJ SINGH LS 121131Z GANDEPALLI SRINIVAS PO 127026Y KANDI CHAND PO 178245B PARITOSH DAS MCPO-II -

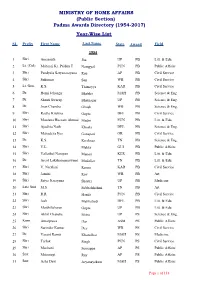

(1954-2014) Year-Wise List 1954

MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS (Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2014) Year-Wise List Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field 1954 1 Dr. Sarvapalli Radhakrishnan BR TN Public Affairs 2 Shri Chakravarti Rajagopalachari BR TN Public Affairs 3 Shri Chandrasekhara Raman BR TN Science & Venkata 4 Dr. Satyendra Nath Bose PV WB Litt. & Edu. 5 Shri Nandlal Bose PV WB Art 6 Dr. Zakir Husain PV AP Public Affairs 7 Shri Bal Gangadhar Kher PV MAH Public Affairs 8 Shri V.K. Krishna Menon PV KER Public Affairs 9 Shri Jigme Dorji Wangchuk PV BHU Public Affairs 10 Dr. Homi Jehangir Bhabha PB MAH Science & 11 Dr. Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar PB UP Science & 12 Shri Mahadeva Iyer Ganapati PB OR Civil Service 13 Dr. Jnan Chandra Ghosh PB WB Science & 14 Shri Radha Krishna Gupta PB DEL Civil Service 15 Shri Maithilisharan Gupta PB UP Litt. & Edu. 16 Shri R.R. Handa PB PUN Civil Service 17 Shri Amarnath Jha PB UP Litt. & Edu. 21 May 2014 Page 1 of 193 Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field 18 Shri Ajudhia Nath Khosla PB DEL Science & 19 Dr. K.S. Krishnan PB TN Science & 20 Shri Moulana Hussain Madni PB PUN Litt. & Edu. Ahmad 21 Shri Josh Malihabadi PB DEL Litt. & Edu. 22 Shri V.L. Mehta PB GUJ Public Affairs 23 Shri Vallathol Narayan Menon PB KER Litt. & Edu. 24 Dr. Arcot Mudaliar PB TN Litt. & Edu. Lakshamanaswami 25 Lt. (Col) Maharaj Kr. Palden T Namgyal PB PUN Public Affairs 26 Shri V. Narahari Raooo PB KAR Civil Service 27 Shri Pandyala Rau PB AP Civil Service Satyanarayana 28 Shri Jamini Roy PB WB Art 29 Shri Sukumar Sen PB WB Civil Service 30 Shri Satya Narayana Shastri PB UP Medicine 31 Late Smt. -

(Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2017) Year-Wise List

MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS (Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2017) Year-Wise List SL Prefix First Name Last Name State Award Field 1954 1 Shri Amarnath Jha UP PB Litt. & Edu. 2 Lt. (Col) Maharaj Kr. Palden T Namgyal PUN PB Public Affairs 3 Shri Pandyala Satyanarayana Rau AP PB Civil Service 4 Shri Sukumar Sen WB PB Civil Service 5 Lt. Gen. K.S. Thimayya KAR PB Civil Service 6 Dr. Homi Jehangir Bhabha MAH PB Science & Eng. 7 Dr. Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar UP PB Science & Eng. 8 Dr. Jnan Chandra Ghosh WB PB Science & Eng. 9 Shri Radha Krishna Gupta DEL PB Civil Service 10 Shri Moulana Hussain Ahmad Madni PUN PB Litt. & Edu. 11 Shri Ajudhia Nath Khosla DEL PB Science & Eng. 12 Shri Mahadeva Iyer Ganapati OR PB Civil Service 13 Dr. K.S. Krishnan TN PB Science & Eng. 14 Shri V.L. Mehta GUJ PB Public Affairs 15 Shri Vallathol Narayan Menon KER PB Litt. & Edu. 16 Dr. Arcot Lakshamanaswami Mudaliar TN PB Litt. & Edu. 17 Shri V. Narahari Raooo KAR PB Civil Service 18 Shri Jamini Roy WB PB Art 19 Shri Satya Narayana Shastri UP PB Medicine 20 Late Smt. M.S. Subbalakshmi TN PB Art 21 Shri R.R. Handa PUN PB Civil Service 22 Shri Josh Malihabadi DEL PB Litt. & Edu. 23 Shri Maithilisharan Gupta UP PB Litt. & Edu. 24 Shri Akhil Chandra Mitra UP PS Science & Eng. 25 Kum. Amalprava Das ASM PS Public Affairs 26 Shri Surinder Kumar Dey WB PS Civil Service 27 Dr. Vasant Ramji Khanolkar MAH PS Medicine 28 Shri Tarlok Singh PUN PS Civil Service 29 Shri Machani Somappa AP PS Public Affairs 30 Smt. -

Indian Modern Dance, Feminism and Transnationalism New World Choreographies Series Editors: Rachel Fensham and Peter M

Indian Modern Dance, Feminism and Transnationalism New World Choreographies Series Editors: Rachel Fensham and Peter M. Boenisch Editorial Advisory Board: Ric Allsop, Falmouth University, UK, Susan Leigh Foster, UCLA, USA, Lena Hammergren, University of Stockholm, Sweden, Gabriele Klein, University of Hamburg, Germany, Andre Lepecki, NYU, USA and Avanthi Meduri, Roehampton University, UK New World Choreographies presents advanced yet accessible studies of a rich field of new choreographic work which is embedded in the global, transna- tional and intermedial context. It introduces artists, companies and scholars who contribute to the conceptual and technological rethinking of what constitutes movement, blurring old boundaries between dance, theatre and performance. The series considers new aesthetics and new contexts of production and pres- entation, and discusses the multi-sensory, collaborative and transformative potential of these new world choreographies. Titles include: Gretchen Schiller and Sarah Rubidge (editors) CHOREOGRAPHIC DWELLINGS Practising Place Forthcoming titles: Pil Hansen and Darcey Callison (editors) DANCE DRAMATURGY Royona Mitra AKRAM KHAN Dancing New Interculturalism New World Choreographies Series Standing Order ISBN 978–1–137–35986–5 (hardback) (outside North America only) You can receive future titles in this series as they are published by placing a standing order. Please contact your bookseller or, in case of difficulty, write to us at the address below with your name and address, the title of the series and the ISBN quoted above. Customer Services Department, Macmillan Distribution Ltd, Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS, England Indian Modern Dance, Feminism and Transnationalism Prarthana Purkayastha Plymouth University, UK © Prarthana Purkayastha 2014 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 2014 978-1-137-37516-2 All rights reserved.