Contemporary Georgian Fiction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dušan Šarotar, Born in Murska Sobota +386 1 200 37 07 in 1968, Is a Writer, Poet and Screenwri- [email protected] Ter

Foreign Rights Beletrina Academic Press About the Author (Študentska založba) Renata Zamida Borštnikov trg 2 SI-1000 Ljubljana Dušan Šarotar, born in Murska Sobota +386 1 200 37 07 in 1968, is a writer, poet and screenwri- [email protected] ter. He studied Sociology of Culture and www.zalozba.org Philosophy at the University of Ljublja- www.readcentral.org na. He has published two novels (Island of the Dead in 1999 and Billiards at the Translation: Gregor Timothy Čeh Dušan Šarotar Hotel Dobray in 2007), three collecti- ons of short stories (Blind Spot, 2002, Editor: Renata Zamida Author’s Catalogue Layout: designstein.si Bed and Breakfast, 2003 and Nostalgia, Photo: Jože Suhadolnik, Dušan Šarotar 2010) and three poetry collections (Feel Proof-reading: Catherine Fowler, for the Wind, 2004, Landscape in Minor, Marianne Cahill 2006 and The House of My Son, 2009). Ša- rotar also writes puppet theatre plays Published by Beletrina Academic Press© and is author of fifteen screenplays for Ljubljana, 2012 documentary and feature films, mostly for television. The author’s poetry and This publication was published with prose have been included into several support of the Slovene Book Agency: anthologies and translated into Hunga- rian, Russian, Spanish, Polish, Italian, Czech and English. In 2008, the novel Billiards at the Hotel Dobray was nomi- nated for the national Novel of the Year Award. There will be a feature film ba- ISBN 978-961-242-471-8 sed on this novel filmed in 2013. Foreign Rights Beletrina Academic Press About the Author (Študentska založba) Renata Zamida Borštnikov trg 2 SI-1000 Ljubljana Dušan Šarotar, born in Murska Sobota +386 1 200 37 07 in 1968, is a writer, poet and screenwri- [email protected] ter. -

The Myth of the City in the French and the Georgian Symbolist Aesthetics

The International Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities Invention 5(03): 4519-4525, 2018 DOI: 10.18535/ijsshi/v5i3.07 ICV 2015: 45.28 ISSN: 2349-2031 © 2018, THEIJSSHI Research Article The Myth of the City in the French and the Georgian Symbolist Aesthetics Tatia Oboladze PhD student at Ivane Javakhisvhili Tbilisi State University, Tbilisi, Georgia,young-researcher at Shota Rustaveli Institute of Georgian Literature ―Modern Art is a genuine offspring of the city… the city The cultural contexts of the two countries were also different. created new images, here the foundation was laid for the If in the 19th-c. French literature the tendencies of literary school, known as Symbolism…The poet’s Romanticism and Realism (with certain variations) co-existed consciousness was burdened by the gray iron city and it and it was distinguished by paradoxes, striving towards poured out into a new unknown song‖ (Tabidze 2011: 121- continuous formal novelties, the beginning of the 20th c. was 122), - writes Georgian Symbolist Titsian Tabidze in his the period of stagnation of Georgian culture. Although in the program article Tsisperi Qantsebit (With Blue Horns). Indeed, work of individual authors (A.Abasheli, S.Shanshiashvili, in the Symbolist aesthetics the city-megalopolis, as a micro G.Tabidze, and others) aesthetic features of modernism, model of the material world, is formed as one of the basic tendencies of new art were observable, on the whole, literature concepts. was predominated by epigonism1. Against this background, in Within the topic under study we discuss the work of Charles 1916, the first Symbolist literary group Tsisperi Qantsebi (The Baudelaire and the poets of the Georgian Symbolist school Blue Horns) came into being in the Georgian literary area. -

Fall 2011 / Winter 2012 Dalkey Archive Press

FALL 2011 / WINTER 2012 DALKEY ARCHIVE PRESS CHAMPAIGN - LONDON - DUBLIN RECIPIENT OF THE 2010 SANDROF LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT Award FROM THE NatiONAL BOOK CRITICS CIRCLE what’s inside . 5 The Truth about Marie, Jean-Philippe Toussaint 6 The Splendor of Portugal, António Lobo Antunes 7 Barley Patch, Gerald Murnane 8 The Faster I Walk, the Smaller I Am, Kjersti A. Skomsvold 9 The No World Concerto, A. G. Porta 10 Dukla, Andrzej Stasiuk 11 Joseph Walser’s Machine, Gonçalo M. Tavares Perfect Lives, Robert Ashley (New Foreword by Kyle Gann) 12 Best European Fiction 2012, Aleksandar Hemon, series ed. (Preface by Nicole Krauss) 13 Isle of the Dead, Gerhard Meier (Afterword by Burton Pike) 14 Minuet for Guitar, Vitomil Zupan The Galley Slave, Drago Jančar 15 Invitation to a Voyage, François Emmanuel Assisted Living, Nikanor Teratologen (Afterword by Stig Sæterbakken) 16 The Recognitions, William Gaddis (Introduction by William H. Gass) J R, William Gaddis (New Introduction by Robert Coover) 17 Fire the Bastards!, Jack Green 18 The Book of Emotions, João Almino 19 Mathématique:, Jacques Roubaud 20 Why the Child is Cooking in the Polenta, Aglaja Veteranyi (Afterword by Vincent Kling) 21 Iranian Writers Uncensored: Freedom, Democracy, and the Word in Contemporary Iran, Shiva Rahbaran Critical Dictionary of Mexican Literature (1955–2010), Christopher Domínguez Michael 22 Autoportrait, Edouard Levé 23 4:56: Poems, Carlos Fuentes Lemus (Afterword by Juan Goytisolo) 24 The Review of Contemporary Fiction: The Failure Issue, Joshua Cohen, guest ed. Available Again 25 The Family of Pascual Duarte, Camilo José Cela 26 On Elegance While Sleeping, Viscount Lascano Tegui 27 The Other City, Michal Ajvaz National Literature Series 28 Hebrew Literature Series 29 Slovenian Literature Series 30 Distribution and Sales Contact Information JEAN-PHILIPPE TOUSSAINT titles available from Dalkey Archive Press “Right now I am teaching my students a book called The Bathroom by the Belgian experimentalist Jean-Philippe Toussaint—at least I used to think he was an experimentalist. -

Dvigubski Full Dissertation

The Figured Author: Authorial Cameos in Post-Romantic Russian Literature Anna Dvigubski Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 Anna Dvigubski All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Figured Author: Authorial Cameos in Post-Romantic Russian Literature Anna Dvigubski This dissertation examines representations of authorship in Russian literature from a number of perspectives, including the specific Russian cultural context as well as the broader discourses of romanticism, autobiography, and narrative theory. My main focus is a narrative device I call “the figured author,” that is, a background character in whom the reader may recognize the author of the work. I analyze the significance of the figured author in the works of several Russian nineteenth- and twentieth- century authors in an attempt to understand the influence of culture and literary tradition on the way Russian writers view and portray authorship and the self. The four chapters of my dissertation analyze the significance of the figured author in the following works: 1) Pushkin's Eugene Onegin and Gogol's Dead Souls; 2) Chekhov's “Ariadna”; 3) Bulgakov's “Morphine”; 4) Nabokov's The Gift. In the Conclusion, I offer brief readings of Kharms’s “The Old Woman” and “A Fairy Tale” and Zoshchenko’s Youth Restored. One feature in particular stands out when examining these works in the Russian context: from Pushkin to Nabokov and Kharms, the “I” of the figured author gradually recedes further into the margins of narrative, until this figure becomes a third-person presence, a “he.” Such a deflation of the authorial “I” can be seen as symptomatic of the heightened self-consciousness of Russian culture, and its literature in particular. -

Number of Libraries 1 Akaki Tsereteli State University 2 Batumi

№ Number of libraries 1 Akaki Tsereteli State University 2 Batumi Navigation Teaching University 3 Batumi Shota Rustaveli State University 4 Batumi State Maritime Academy 5 Business and Technology University 6 Caucasus International University 7 Caucasus University 8 Collage Iberia 9 David Agmashenebeli University of Georgia 10 David Tvildiani Medical University 11 East European University 12 European University 13 Free Academy of Tbilisi 14 Georgian American University (GAU) 15 Georgian Aviation University 16 Georgian Patriarchate Saint Tbel Abuserisdze Teaching University 17 Georgian state teaching university of physical education and sport education and sport 18 Georgian Technical University 19 Gori State Teaching University 20 Guram Tavartkiladze Tbilisi Teaching University 21 Iakob Gogebashvili Telavi State University 22 Ilia State University 23 International Black Sea University 24 Korneli Kekelidze Georgian National Centre of Manuscripts 25 Kutaisi Ilia Tchavtchavadze Public Library 26 LEPL - Vocational College "Black Sea" 27 LEPL Vocational College Lakada 28 LTD East-West Teaching University 29 LTD Kutaisi University 30 LTD Schllo IB Mtiebi 31 LTD Tbilisi Free School 32 National Archives of Georgia 33 National University of Georgia (SEU) 34 New Higher Education Institute 35 New Vision University (NVU) 36 Patriarchate of Georgia Saint King Tamar University 37 Petre Shotadze Tbilisi Medical Academy 38 Public Collage MERMISI 39 Robert Shuman European School 40 Samtskhe-Javakheti State Teaching University 41 Shota Meskhia Zugdidi State Teaching University 42 Shota Rustaveli theatre and Film Georgia State University 43 St. Andrews Patriarchate Georgian University 44 Sulkhan-Saba Orbeliani University 45 Tbilisi Humanitarian Teaching University 46 Tbilisi open teaching University 47 Tbilisi State Academy of Arts 48 Tbilisi State Medical University (TSMU) 49 TSU National Scientific Library. -

Prenesi Datoteko Prenesi

From War to Peace: The Literary Life of Georgia after the Second World War Irma Ratiani Ivane Javakhishvili, Tbilisi State University, Shota Rustaveli Institute of Georgian Literature, 1 Chavchavadze Ave, Tbilisi 0179, Georgia [email protected] After the Second World War, political changes occurred in the Soviet Union. In 1953 Joseph Stalin—originally Georgian and the incarnate symbol of the country— died, and soon the much-talked-about Twentieth Assembly of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union headed by Nikita Khrushchev followed in 1956. In Georgia, Khrushchev’s speech against Stalin was followed by serious political unrest that ended with the tragic events of March 9th, 1956. It is still unclear whether this was a political event or demonstration of insulted national pride. Soon after that, the Khrushchev Thaw (Russian: Ottepel) occurred throughout the Soviet Union. The literary process during the Thaw yielded quite a different picture compared to the previous decades of Soviet life. Under the conditions of political liberalization, various tendencies were noticed in Georgian literary space: on the one hand, there was an obvious nostalgia for Stalin, and on the other hand there was the growth of a specific model of Neo-Realism and, of no less importance, the rise of women’s writing. Keywords: literature and ideology / Georgian literature / World War II / Khrushchev thaw / Soviet Union Modifications of the Soviet regime Georgian literature before the Second World War was by no means flourishing. As a result of the political purges of the 1930s conducted by Soviet government, the leading Georgian writers were elimi- nated. -

Georgia's Technology Needs Assessment

ANNEX MAIN CHARACTERISTICS OF GEORGIAN POWER PLANTS by the state of 1990 and 1999 TABLE 1-1 Installed capacity, Designed output of Actual generation of Installed capacity use factor Actual generation of No Electricity generation plants electricity, electricity, Designed Actual thermal energy, MW Thousand KWh Thousand KWh % % MWh 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 THERMAL ELECTRIC STATIONS 1990 1999 1990 1999 1990 1999 1990 1999 1990 1999 1990 1999 1 Tbilsresi 1400 1700 8400 10200 5578.1 1609,6 68,49 68,49 45,48 10,8 103982 1163 2 Tkvarchelsresi 220 0 1320 0 344 0 68,49 0 17,9 0 0 0 3 Tbiltetsi (Tbilisi CHP) 18 18 108 108 96,2 24,2 68,49 68,49 61 15,34 437015 32010 Total for thermal electric plants 1638 1718 9828 10308 6018,3 1633,8 68,49 68,49 41,94 10,35 540997 33173 HYDRO POWER PLANTS 1990 1999 1990 1999 1990 1999 1990 1999 1990 1999 1990 1999 4 Engurhesi 1300 1300 4340 4340 3579,3 2684,1 38,11 38,11 31,43 23,56 - - 5 Vardnilhesi-1 220 220 700 700 643,6 525,4 36,32 36,32 33,39 27,26 - - 6 Vardnilhesi-2 40 0 127 0 116 0 36,24 0 33,11 0 - - 7 Vardnilhesi-3 40 0 127 0 112,9 0 36,24 0 32,22 0 - - 8 Vardnilhesi-4 40 0 137 0 112,5 0 39,09 0 32,1 0 - - 9 Khramhesi-1 113,45 113,45 217 217 198,2 217,1 21,83 21,83 19,94 21,83 - - 10 Khramhesi-2 110 110 370 370 285,3 207,5 38,39 38,39 29,6 21,53 - - 11 Jinvalhesi 130 130 500 500 361,6 362 43,9 53,9 31,75 31,78 - - 12 Shaorhesi 38,4 38,4 148 148 134,7 167,2 43,99 43,99 40,04 49,7 - - 13 Tkibulhesi 80 80 165 165 165,9 133,8 23,54 23,54 23,67 19,09 - - 14 Rionhesi 48 48 325 325 247,2 243.8 77,25 77,25 58,76 58,76 - -

Georgian Symbolism: Context and Influence

International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English Literature E-ISSN: 2200-3452 & P-ISSN: 2200-3592 www.ijalel.aiac.org.au Georgian Symbolism: Context and Influence Tatia Oboladze* Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University, Tbilisi, Georgia Corresponding Author: Tatia Oboladze, E-mail: [email protected] ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history In the 1910s in the Georgian literary area the first Symbolist group TsisperiQantsebi (The Blue Received: November 18, 2017 Horns) comes into being, with a clearly defined purpose and aesthetic position, which implied Accepted: January 27, 2018 renewing the Georgian literature and including it into the Western context. Desiring to expand Published: March 01, 2018 the thought area and to modernize Georgian literature, Georgian Symbolists rested on the Volume: 7 Issue: 2 philosophical and worldview principles of French Symbolism. Georgian Symbolism appears Advance access: February 2018 as an original invariant generated from the French Symbolist aesthetics, which is unequivocally national. Conflicts of interest: None Funding: None Key words: Georgian Symbolism, Georgian Modernism, The Blue Horns In 1916, when European, namely French Symbolism in also by their public activities performed an enormous role fact was a completed project, the first Symbolist literary in the process of Europeanization of Georgian literature and group Tsisperi Qantsebi (The Blue Horns)1 came into being transformation of Georgia into a cultural centre, in general. in Georgia. Young poets united to achieve a common objec- The socio-political and cultural context of France of the tive, which implied restoring the artificially broken connec- 19th c. and Georgia of the early 20th c. were totally different. tion of Georgian literature with the Western area. -

Georgian Country and Culture Guide

Georgian Country and Culture Guide მშვიდობის კორპუსი საქართველოში Peace Corps Georgia 2017 Forward What you have in your hands right now is the collaborate effort of numerous Peace Corps Volunteers and staff, who researched, wrote and edited the entire book. The process began in the fall of 2011, when the Language and Cross-Culture component of Peace Corps Georgia launched a Georgian Country and Culture Guide project and PCVs from different regions volunteered to do research and gather information on their specific areas. After the initial information was gathered, the arduous process of merging the researched information began. Extensive editing followed and this is the end result. The book is accompanied by a CD with Georgian music and dance audio and video files. We hope that this book is both informative and useful for you during your service. Sincerely, The Culture Book Team Initial Researchers/Writers Culture Sara Bushman (Director Programming and Training, PC Staff, 2010-11) History Jack Brands (G11), Samantha Oliver (G10) Adjara Jen Geerlings (G10), Emily New (G10) Guria Michelle Anderl (G11), Goodloe Harman (G11), Conor Hartnett (G11), Kaitlin Schaefer (G10) Imereti Caitlin Lowery (G11) Kakheti Jack Brands (G11), Jana Price (G11), Danielle Roe (G10) Kvemo Kartli Anastasia Skoybedo (G11), Chase Johnson (G11) Samstkhe-Javakheti Sam Harris (G10) Tbilisi Keti Chikovani (Language and Cross-Culture Coordinator, PC Staff) Workplace Culture Kimberly Tramel (G11), Shannon Knudsen (G11), Tami Timmer (G11), Connie Ross (G11) Compilers/Final Editors Jack Brands (G11) Caitlin Lowery (G11) Conor Hartnett (G11) Emily New (G10) Keti Chikovani (Language and Cross-Culture Coordinator, PC Staff) Compilers of Audio and Video Files Keti Chikovani (Language and Cross-Culture Coordinator, PC Staff) Irakli Elizbarashvili (IT Specialist, PC Staff) Revised and updated by Tea Sakvarelidze (Language and Cross-Culture Coordinator) and Kakha Gordadze (Training Manager). -

13. Giorgi Chigvaria, Tariel Chigvaria, the New Phase of Turkish-Armenian Relations

CV Name: Giorgi Surname: Chigvaria Date of Birth: April 20, 1980 Nationality/Citizenship: Georgian/Georgia Address: P. Iashvili street N46, Kutaisi, Georgia Tel: 596-12-12-21 e-mail: [email protected] Education From 2010 - Academic Doctor of History at Akaki Tseretei State University 2002–2003 - Turkish ,,ankara universitesi” Language School; 2002–2003 – Researcher at Turkish ,,ankara universitesi”; 1998–2003 – Independent University of Kutaisi, majoring in Law 1997–2002 – AAkaki Tsereteli State University, Faculty of History, majoring in History of Eastern Countries; 1995–1997 - Kutaisi Humanitarian School; 1986–1995 Kutaisi N3 Secondary School; Political and Social Activities 2016 – Head of Kutaisi election headquarter district organization of the party “Georgian Dream-Democratic Georgia” on parliamentary elections; 2016 – to present: Head of Kutaisi district organization of the party “Georgian Dream-Democratic Georgia; 2015 – 2017 – Vice governor of Imereti Region; 2014 – Advisor of Kutaisi City Mayor; 2014 – Acting advisor of Kutaisi City Mayor; 2014 – Member of the commission on contest to fill the vacancy of Academic staff in Social and Political Sciences faculty of Batumi Shota Rustaveli State University, majoring in Sociology, demography, International Relations and History; 2014 – to presen: Associate professor of the Faculty of Social Sciences at Akaki Tsereteli State University; 2014 - Deputy Coordinator of Kutaisi and lower Imereti Region on local self-government elections from the party of “Georgian Dream-Democratic -

The Central Europe of Yuri Andrukhovych and Andrzej Stasiuk

Rewriting Europe: The Central Europe of Yuri Andrukhovych and Andrzej Stasiuk Ariko Kato Introduction When it joined the European Union in 2004, Poland’s eastern bor- der, which it shared with Ukraine and Belarus, became the easternmost border of the EU. In 2007, Poland was admitted to the Schengen Con- vention. The Polish border then became the line that effectively divided the EU identified with Europe from the “others” of Europe. In 2000, on the eve of the eastern expansion of the EU, Polish writer Andrzej Stasiuk (1960) and Ukrainian writer Yuri Andrukhovych (1960) co-authored a book titled My Europe: Two Essays on So-called Central Europe (Moja Europa: Dwa eseje o Europie zwanej Środkową). The book includes two essays on Central Europe, each written by one of the authors. Unlike Milan Kundera, who discusses Central Europe as “a kidnapped West” which is “situated geographically in the center—cul- turally in the West and politically in the East”1 in his well-known essay “A Kidnapped West, or the Tragedy of Central Europe” (“Un Occident kidnappé ou la tragédie de l’Europe centrale”) (1983),2 written in the Cold War period, they describe Central Europe neither as a corrective concept nor in terms of the binary opposition of West and East. First, as the subtitle of this book suggests, they discuss Central Europe as “my 1 Milan Kundera, “A Kidnapped West or Culture Bows Out,” Granta 11 (1984), p. 96. 2 The essay was originally published in French magazine Le Débat 27 (1983). - 91 - Ariko Kato Europe,” drawing from their individual perspectives. -

Dr. Earl Davis Is Always Busy with University of Texas at Austin and Completed His One Task Or Another

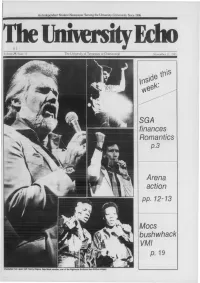

An Independent Student Newspaper Serving the University Community Since 1906 The University Echo <?3 • .-. W Volume/?f?/Issue The University of Tennessee at Chattanooga November II, 1983 SGA finances Romantics p.3 Arena action pp. 12-13 Mocs bushwhack VMI p. 19 Clockwise Irom upper left: Kenny Rogers, Gap Band member, one of the Righteous Brothers, New Edition singers. "Our Personnel Touch guarantees you quality service. Thanks tn Pi tWa Phi f„r rhi, pi.-t..,-,- I'II niri-fl ni-n rimis-.Li ^^'inrlniH Echo News 2 The Echo/November 11, 1983 No pay raise this year UTC faculty salaries below average By Sandy Fye Echo News Editor UTC will need $903,600 to bring faculty salaries up 155 and over stay, then there's no room for new faculty. to Southern Region Education Board (SREB) And we can't afford to retire. averages, according to information compiled by Dave To reach 1982-1983 fiscal year faculty pay "On the whole, I think we've got the best teaching Larson, vice chancellor of administration and finance, averages: faculty in the state," continued Printz. "But it makes in his "Planning for Excellence" report. 66 professors need an average of $2755 each you sort of sad that you can't afford to send your Because report figures were based on 1982-83 109 associate professors need an average of children somewhere else, so they won't be burdened SREB averages, much more money will be necessary $2330 each by having a parent on campus." to raise the salary level to the current average as the 85 assistant professors need an average of $2798 Printz said many former UTC faculty and staff UTC faculty did not receive pay raises for 1983 84, for each members have relocated to other jobs or out of the cost-of-living or otherwise.