In Georgia (2003-2012)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Georgia's Technology Needs Assessment

ANNEX MAIN CHARACTERISTICS OF GEORGIAN POWER PLANTS by the state of 1990 and 1999 TABLE 1-1 Installed capacity, Designed output of Actual generation of Installed capacity use factor Actual generation of No Electricity generation plants electricity, electricity, Designed Actual thermal energy, MW Thousand KWh Thousand KWh % % MWh 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 THERMAL ELECTRIC STATIONS 1990 1999 1990 1999 1990 1999 1990 1999 1990 1999 1990 1999 1 Tbilsresi 1400 1700 8400 10200 5578.1 1609,6 68,49 68,49 45,48 10,8 103982 1163 2 Tkvarchelsresi 220 0 1320 0 344 0 68,49 0 17,9 0 0 0 3 Tbiltetsi (Tbilisi CHP) 18 18 108 108 96,2 24,2 68,49 68,49 61 15,34 437015 32010 Total for thermal electric plants 1638 1718 9828 10308 6018,3 1633,8 68,49 68,49 41,94 10,35 540997 33173 HYDRO POWER PLANTS 1990 1999 1990 1999 1990 1999 1990 1999 1990 1999 1990 1999 4 Engurhesi 1300 1300 4340 4340 3579,3 2684,1 38,11 38,11 31,43 23,56 - - 5 Vardnilhesi-1 220 220 700 700 643,6 525,4 36,32 36,32 33,39 27,26 - - 6 Vardnilhesi-2 40 0 127 0 116 0 36,24 0 33,11 0 - - 7 Vardnilhesi-3 40 0 127 0 112,9 0 36,24 0 32,22 0 - - 8 Vardnilhesi-4 40 0 137 0 112,5 0 39,09 0 32,1 0 - - 9 Khramhesi-1 113,45 113,45 217 217 198,2 217,1 21,83 21,83 19,94 21,83 - - 10 Khramhesi-2 110 110 370 370 285,3 207,5 38,39 38,39 29,6 21,53 - - 11 Jinvalhesi 130 130 500 500 361,6 362 43,9 53,9 31,75 31,78 - - 12 Shaorhesi 38,4 38,4 148 148 134,7 167,2 43,99 43,99 40,04 49,7 - - 13 Tkibulhesi 80 80 165 165 165,9 133,8 23,54 23,54 23,67 19,09 - - 14 Rionhesi 48 48 325 325 247,2 243.8 77,25 77,25 58,76 58,76 - -

Liberalism and Georgia

Ilia Chavchavadze Center for European Studies and Civic Education Liberalism and Georgia Tbilisi 2020 Liberalism and Georgia © NCLE Ilia Chavchavadze Center for European Studies and Civic Edu- cation, 2020 www.chavchavadzecenter.ge © Authors: Teimuraz Khutsishvili, Nino Kalandadze, Gaioz (Gia) Japaridze, Giorgi Jokhadze, Giorgi Kharebava, 2020 Editor-in-chief: Zaza Bibilashvili Editor: Medea Imerlishvili The publication has been prepared with support from the Konrad-Ad- enauer-Stiftung South Caucasus within the framework of the project “Common Sense: Civil Society vis-à-vis Politics.” The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily rep- resent those of the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung South Caucasus. This content may not be reproduced, copied or distributed for commercial purposes without expressed written consent of the Center. The Ilia Chavchavadze Center extends its thanks to Dr. David Mai- suradze, a Professor at Caucasus University, and students Nika Tsilosani and Ana Lolua for the support they provided to the publication. Layout designer: Irine Stroganova Cover page designer: Tamar Garsevanishvili ISBN 978-9941-31-292-2 TABLE OF CONTENTS THE CENTER’S FORWORD .................................................................5 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................7 CHAPTER I – WHAT IS LIBERALISM? ..............................................9 Historical understanding of liberalism ..........................................9 Formation of -

The Essence of Economic Reforms in Post- Revolution Georgia: What About the European Choice?

Georgian International Journal of Science and Technology ISSN 1939-5825 Volume 1, Issue 1, pp. 1-9 © 2008 Nova Science Publishers, Inc. THE ESSENCE OF ECONOMIC REFORMS IN POST- REVOLUTION GEORGIA: WHAT ABOUT THE EUROPEAN CHOICE? Vladimer Papava* Georgian Foundation for Strategic and International Studies Several countries in the post-Soviet world have completed the transition to a European- type market economy and have been admitted to the European Union. For others—either partly or totally unsuccessful in transitioning—the question of whether or not this kind of market economy could be built is not even discussed. As to the potential of EU membership, such countries have either never set such a goal for themselves or, at best, are considering it in a long-term perspective. It is no secret that Georgia is not ready to join the EU in the near future. In view of continual official statements regarding Georgia’s striving toward Euro-Atlantic organisations (see Papava and Tokmazishvili, 2006), however, we should know where we are going. One of the most important aspects is the vector of Georgia’s economic development. If we see Georgia as part of Europe—even if not fully accepted until the distant future—Georgia must transform into a European-type market economy. THE EU’S ECONOMIC MODEL AND GEORGIA It is not easy to describe the EU’s economic model, which is still in formation (Fioretos, 2003). According to Albert (1991), the EU has been a battlefield of the two key models of capitalism, i.e., the Anglo-American and the “Rhenish” (German-Japanese) ones. -

Economic Liberalism in Georgia a Challenge for EU Convergence and Trade Unions

PERSPECTIVE | FES TBILISI Economic Liberalism in Georgia A Challenge for EU Convergence and Trade Unions MATTHIAS JOBELIUS April 2011 n Two decades after the end of real existing socialism in Georgia, ideology has again become a problem – this time emanating from the far right. Important econo- mic policy makers subscribe to a radical libertarianism. They fundamentally reject intervention in the economy, and provision of public goods such as education and health care by the state. n The government’s anti-regulatory economic policy slows down the country’s conver- gence with the EU. The refusal to strengthen economic regulatory authorities is directly at odds with the need to adopt European standards and regulatory procedures. n Georgia passed a new Labour Code in 2006 that is widely regarded as one of the world‘s most unfavourable towards employees. The dismantling of employee and trade union rights in the wake of this law brings Georgia into conflict with ILO core labour standards and the European Social Charter. Instead of a reform of the Labour Code, the country‘s trade unions are systematically put under pressure. n Anyone opting for a libertarian experiment such as the one in Georgia also opts for an authoritarian government style. The drastic structural adjustments would not be enforceable in any other way. The ideology-bound economic policy is therefore directly linked to the country’s deficit in terms of democracy. MATTHIAS JOBELIUS | ECONOMIC LIBERALISM IN GEORGIA 1. When Ideology Becomes a Problem the government for help is like trusting a drunk to do surgery on your brain.«1 The majority of international observers writing about Georgia’s economy take a positive view. -

Emerson's Hidden Influence: What Can Spinoza Tell the Boy?

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Philosophy Honors Theses Department of Philosophy 6-15-2007 Emerson's Hidden Influence: What Can Spinoza Tell the Boy? Adam Adler Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/philosophy_hontheses Recommended Citation Adler, Adam, "Emerson's Hidden Influence: What Can Spinoza Tell the Boy?." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2007. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/philosophy_hontheses/2 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Philosophy at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Philosophy Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EMERSON’S HIDDEN INFLUENCE: WHAT CAN SPINOZA TELL THE BOY? by ADAM ADLER Under the Direction of Reiner Smolinski and Melissa Merritt ABSTRACT Scholarship on Emerson to date has not considered Spinoza’s influence upon his thought. Indeed, from his lifetime until the twentieth century, Emerson’s friends and disciples engaged in a concerted cover-up because of Spinoza’s hated name. However, Emerson mentioned his respect and admiration of Spinoza in his journals, letters, lectures, and essays, and Emerson’s thought clearly shows an importation of ideas central to Spinoza’s system of metaphysics, ethics, and biblical hermeneutics. In this essay, I undertake a biographical and philosophical study in order to show the extent of Spinoza’s influence on Emerson and -

DCFTA) – Is There a European Way for Georgia?1

Prospect of Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area Prospect of Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area (DCFTA) – Is there a European Way for Georgia?1 Tamar Khuntsaria CSS Affiliated Fellow Abstract The negotiations on a Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area (DCFTA) with the European Union (EU) are an important element of the current agenda of the EU-Georgia relations. Political dialogue between the Government of Georgia and the European Commission on DCFTA commenced soon after the August war in 2008 and aimed at opening official negotiations on DCFTA once structural and policy reforms set forth as preconditions by the EU were launched in Georgia. Early in 2010, official Tbilisi asserted that it had made a substantial progress with respect to the Commission‘s preconditions. Nonetheless, the Commission postponed the opening of official negotiations to January 2012 and announced DCFTA to be an integral part of the projected Association Agreement (AA) with Georgia – a far reaching and ambitious, and therefore, a lengthy document to conclude. This paper offers analysis of the possible impediments to concluding a DCFTA with Georgia. My arguments are based on three major factors hindering the process: First and foremost, Georgia‘s long term economic development model is uncertain. The country‘s ruling elite up until 2012 parliamentary election, dominated by an influential libertarian group, has maintained the government‘s ambivalent attitude towards the two fundamentally different ‗European‘ and ‗Singaporean‘ models of country‘s development. It is argued here that becoming a second Singapore is an obscure prospect for Georgia and that the best possible alternative for the country‘s long-term sustainable development is to follow the European path. -

Cover Pagr 1999 Eng Small.Jpg

INTERNATIONAL CENTRE for CIVIC CULTURE Political Parties of Georgia Directory 1999 Tbilisi 1999 Publication of the Directory was possible as the result of financial support of INTERNATIONAL REPUBLICAN INSTITUTE (IRI), USA (IRI – Georgia is a grantee of USAID) Special thanks to all people who has supported the ICCC. The directory has been prepared by : Konstantine Kandelaki, Davit Kiphiani, Lela Khomeriki, Salome Tsiskarishvili, Nino Chubinidze, Koba Kiknadze. Translated by: Tamar Bregvadze, Nino Javakhishvili Cover design: Tamaz Varvavridze Layout: Davit Kiphiani ISBN 99928-52-40-0 © INTERNATIONAL CENTRE for CIVIC CULTURE, 1999 Printed in Georgia INTERNATIONAL CENTRE for CIVIC CULTURE Address: 20a, Baku St., Tbilisi, Georgia Phone: (+995 32) 953-873 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: www.iccc.org.ge Political Parties of Georgia INTRODUCTION This directory was created prior to the October 31, 1999 parliament elections for the purpose of providing a complete spectrum of Georgian political parties. Therefore, it was decided to include here not only the parties participating in elections, but all registered political parties. According to the Ministry of Justice of Georgia, as of September 1, 1999, there are 124 political parties registered in Georgia. (79 parties were registered on September 26, 1998) In order to collect the material for this directory, ICCC distributed questionnaires to all 124 registered parties. 93 parties have been included in the directory, 31 parties failed to return the questionnaire. Some claimed they didn’t have adequate time to respond, some of the parties have not been found at the addresses given by the Ministry of Justice and others just refused. -

The Changing Pattern of Social Dialogue in Europe and the Influence of ILO and EU in Georgian Tripartism

The Changing Pattern of Social Dialogue in Europe and the Influence of ILO and EU in Georgian Tripartism The Changing Pattern of Social Dialogue in Europe and the Influence of ILO and EU in Georgian Tripartism Francesco Bagnardi University of Bari Aldo Moro Abstract This paper aims to analyse the establishment of tripartite social dialogue practices at national level in the Republic of Georgia. The introduction of such practice is the result of European Union’s political pressures, International Labour Organization’s technical assistance and international trade unions confederations’ (namely the ETUC and the ITUC) support. After describing the practices of social dialogue in Western and Eastern Europe, the paper outlines, with a comparative viewpoint, the process that led to the establishment of a national commission for a tripartite social dialogue between government and organized social partners in Georgia. A particular attention is paid to the pressure, leverage and technical help provided by the aforementioned international actors in this process. Moreover, the research illustrates the main achievements and failures of tripartitism in Georgia, as well as the principal constraints that limit the effectiveness of this practice. It is therefore analysed the influence that possible future development of tripartite dialogue between government and social partners can have on the social, economic and political development of the country as a whole. Introduction The tripartite Social Dialogue - which includes all types of negotiation, consultation or simply exchange of information between representative of governments, employers and workers - is a fundamental part of the European Social Model (ESM)’s development agenda and a basic inspiring pillar of the International Labour Organization’s (ILO) activities. -

4241-033: Sustainable Urban Transport Investment Program

Initial Environmental Examination November 2018 Project Number: 42414-033 GEO: Sustainable Urban Transport Investment Program – Tranche 2 Marshal Gelovani Avenue and Right Bank Intersection (SUTIP/C/QCBS-3) Prepared by the Municipal Development Fund of Georgia for the Government of Georgia and the Asian Development Bank. This initial environmental examination is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section on ADB’s website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. CONTRACT NO: SUTIP/C/QCBS-3 Detailed Design of Marshal Gelovani Avenue and Right Bank Intersection Initial Environmental Examination Prepared by: Ltd „Eo-“peti 7 Chavchvadze Ave, room 4 Phone: +995 322 90 44 22; Fax: +995 322 90 46 37 Web-site: www.eco-spectri.com November 2018 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS A. Executive Summary ....................................................................................................... 10 B. ENVIRONMENTAL LAWS, STANDARDSAND REGULATIONS ................................................. 21 B.1 Environmental Policies and Laws of Georgia ................................................................. 21 B.2 -

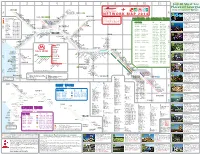

GEORGIAN RAILWAY MAP-ENG-2013-2014-Small

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Top 20 Must See Places of Georgia platf. 44 zugdidi 20 daba dzveli Using Georgian State Railways khresili tkibuli-1 chkefi satsire th ingiri km a tsaishi tkibuli-2 18 a SATAFLIA NATIONAL RESERVE (A-3) tsatskhvi 1 The Sataia State Reserve complex khamiskurA orpiri NETWORK MAP 2014 contains geological, paleontological, kheta kursebi sachkhere speleological and botanical monuments, tskaltubo 1 3 17 19 platf. 19th km including cave, dinosaur footprint munchia Actual train shedules museum, walking trails and viewing JSC Georgian Railway khobi 13 gelati platform. Location: 9 km from the zemo kvaloni Alphabetical railway station nder Passenger and suburban Trains customer information telephones: platf. 15th km Tskaltubo. Entrance fee: 6 GEL. tsivi mendji ternali platf. 45th km Suggestions what to visit in Georgia Diculty: TBILISI 1331 senaki platf. 17th km saFichkhia DARKVETI Tbilisi municipal bus network map (32) 219 86 76 platf. 12th km DZOFI Tbilisi underground network map DAILY TRAINS: GORI (32) 216 39 35 nosiri kutaisi-2 CHIKAURI BATUMI (E-1) agur-karkhana PEREVISA batumi** - ozurgeti 17:30-19:45 7:55-9:58 2 A beautiful seaside resort on the Black Sea KHASHURI (32) 219 83 76 dziguri CHIATURA 11 12 coast and capital of Adjara Autonomous abasha borjomi - bakuriani 7:15-9:40 10:00-12:23 zestafoni (32) 219 82 92 meskheti kutaisi-1 platf. 34th km ffff 7 Republic of Georgia. If you are on kolobani tiri sunbathing and night life, this place is for b KUTAISI (32) 219 83 09 marani samtredia-1 10:55-13:21 14:15-16:32 b samtredia -

Rise of the Georgian Extreme-Right: Lessons from the EU

Rise of the Georgian Extreme-right: Lessons from the EU Tomáš Baranec1 Executive Summary Discussion about the Georgian extreme-right is generally complicated by a lack of conceptualization and very undisciplined use of terms such as fascist or neo-Nazi. The lack of conceptualisation prevents us from properly understanding the character of this phenomenon. The Georgian extreme-right is not a united fascist or neo-Nazi front. Two most prominent groups right from the moderate right, the Alliance of patriots of Georgia (APG) and the Georgian March, are right-wing populist in the first case and extreme-right in the second one. Only quite visible, but still marginal, Georgian unity can be considered to be a truly fascist party. Groups labelled as extreme-right in Georgia are united in their disgust to liberalism, promotion of LGBT rights and Muslim migration. However, they differ significantly in their aims and means. Georgian extreme-right is not a stable and rigid phenomenon. Since 2012, we can observe its evolution on both horizontal and vertical axes. Horizontally, we see a unification of small dispersed groups into a wider movement able to communicate and participate together on rallies. Vertically, these groups which evolved from clusters of mobilized individuals participating in rallies organized by the Church into political parties able to enter parliament or independently stage major counter- rallies. 1 Tomáš Baranec is a graduate of Charles University in Prague. His research interests include nationalism and factors of ethnic conflicts and separatism in the Caucasus. He was part of the Stratpol Young Professionals Program 2018. © 2018 · STRATPOL · [email protected] · +421 908 893 424 · www.stratpol.sk Roots nurturing the growth of the Georgian extreme-right are local. -

42414-023: Impact Evaluation Study of Tbilisi Metro Extension Project

Consultant’s Report August 2012 Impact Evaluation Study of Tbilisi Metro Extension Project (Georgia) Evaluation Design and Baseline Survey Report Prepared by Nina Blöndal International Impact Evaluation Expert for Asian Development Bank (ADB) This consultant’s report does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB or the Government concerned, and ADB and the Government cannot be held liable for its contents. Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY III I. INTRODUCTION iv A. Key Concepts 1 B. Evaluating the Impact of Infrastructure Projects 2 II. THE PROJECT 3 A. Project Overview 3 B. The Tbilisi metro system and project area 3 C. Expected project outcomes 5 D. Project theory and logical framework 7 III. ANALYTICAL FRAMEWORK AND METHODOLOGY 8 A. Theory Based Impact Evaluation 8 B. Evaluation questions 10 C. Evaluation components 10 D. Other components considered 12 E. Evaluation Methodology 13 F. Estimation strategy and sampling 15 G. Other methods considered 16 IV. SUMMARY OF BASELINE SURVEY RESULTS 17 A. The student survey 18 B. The Household Survey 21 C. The Business Survey 23 D. The Qualitative Study 25 V. CONCLUSION AND NEXT STEPS 25 APPENDIX I. DETAILED LITERATURE REVIEW 27 APPENDIX II. MAPOF PROJECT AREA 29 REFERENCES 30 FIGURES Fig. 1 – Transport by source 3 Fig. 2 – Public transport by source 4 Fig. 3 – Student causal chain 8 Fig. 4 – Business causal chain 9 Fig. 5 – Household causal chain 9 Fig. 6 – Difference in difference with valid parallel trend assumption 14 Fig. 7 – Difference in difference with invalid parallel trend assumption