Gothic Ivory Sculpture Content and Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2014 State of Ivory Demand in China

2012–2014 ABOUT WILDAID WildAid’s mission is to end the illegal wildlife trade in our lifetimes by reducing demand through public awareness campaigns and providing comprehensive marine protection. The illegal wildlife trade is estimated to be worth over $10 billion (USD) per year and has drastically reduced many wildlife populations around the world. Just like the drug trade, law and enforcement efforts have not been able to resolve the problem. Every year, hundreds of millions of dollars are spent protecting animals in the wild, yet virtually nothing is spent on stemming the demand for wildlife parts and products. WildAid is the only organization focused on reducing the demand for these products, with the strong and simple message: when the buying stops, the killing can too. Via public service announcements and short form documentary pieces, WildAid partners with Save the Elephants, African Wildlife Foundation, Virgin Unite, and The Yao Ming Foundation to educate consumers and reduce the demand for ivory products worldwide. Through our highly leveraged pro-bono media distribution outlets, our message reaches hundreds of millions of people each year in China alone. www.wildaid.org CONTACT INFORMATION WILDAID 744 Montgomery St #300 San Francisco, CA 94111 Tel: 415.834.3174 Christina Vallianos [email protected] Special thanks to the following supporters & partners PARTNERS who have made this work possible: Beijing Horizonkey Information & Consulting Co., Ltd. Save the Elephants African Wildlife Foundation Virgin Unite Yao Ming Foundation -

Ancient DNA Reveals the Chronology of Walrus Ivory Trade from Norse Greenland

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/289165; this version posted March 27, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Title: Ancient DNA reveals the chronology of walrus ivory trade from Norse Greenland Short title: Tracing the medieval walrus ivory trade Bastiaan Star1*†, James H. Barrett2*†, Agata T. Gondek1, Sanne Boessenkool1* * Corresponding author † These authors contributed equally 1 Centre for Ecological and Evoluionary Synthesis, Department of Biosciences, University of Oslo, PO Box 1066, Blindern, N-0316 Oslo, Norway. 2 McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, Department of Archaeology, University of Cambridge, Downing Street, Cambridge CB2 3ER, United Kingdom. Keywords: High-throughput sequencing | Viking Age | Middle Ages | aDNA | Odobenus rosmarus rosmarus bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/289165; this version posted March 27, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Abstract The search for walruses as a source of ivory –a popular material for making luxury art objects in medieval Europe– played a key role in the historic Scandinavian expansion throughout the Arctic region. Most notably, the colonization, peak and collapse of the medieval Norse colony of Greenland have all been attributed to the proto-globalization of ivory trade. -

China's Ivory Traders Are Moving Online

CHINA’S IVORY AN APPROACH TO THE CONFLICT BETWEEN TRADITION AND ETHICAL RESPONSIBILITY Sophia I. R. Kappus S1994921 [email protected] MA Arts & Culture – Design, Culture & Society Universiteit Leiden Supervisor: Prof. Dr.. R. Zwijnenberg Second Reader: Final Version: 07.12.2017 Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 3 1. The History of Chinese Ivory Carving ..................................................................................... 7 1.1 A Brief overview............................................................................................................ 7 1.2 The Origins and Characteristics of Ivory .......................................................................... 7 1.3 Ivory Carvings throughout history ................................................................................... 9 1.4 From the Material to the Animal – The Elephant in Chinese Culture ................................ 13 2. Ivory in Present Day China................................................................................................... 17 2.1 Chinese National Pride and Cultural Heritage................................................................. 17 2.2 Consumers and Collectors............................................................................................. 19 2.3 The Artist’s Responsibility............................................................................................ 24 -

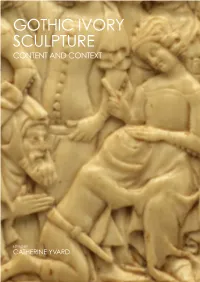

Gothic Ivory Sculpture Content and Context

GOTHIC IVORY SCULPTURE CONTENT AND CONTEXT EDITED BY CATHERINE YVARD Gothic Ivory Sculpture: Content and Context Edited by Catherine Yvard With contributions by: Elisabeth Antoine-König Katherine Eve Baker Camille Broucke Jack Hartnell Franz Kirchweger Juliette Levy-Hinstin Christian Nikolaus Opitz Stephen Perkinson Naomi Speakman Michele Tomasi Catherine Yvard Series Editor: Alixe Bovey Managing Editor: Maria Mileeva Courtauld Books Online is published by the Research Forum of The Courtauld Institute of Art Somerset House, Strand, London WC2R 0RN © 2017, The Courtauld Institute of Art, London. ISBN: 978-1-907485-09-1. Courtauld Books Online is a series of scholarly books published by The Courtauld Institute of Art. The series includes research publications that emerge from Courtauld Research Forum events and Courtauld projects involving an array of outstanding scholars from art history and conservation across the world. It is an open-access series, freely available to readers to read online and to download without charge. The series has been developed in the context of research priorities of The Courtauld which emphasise the extension of knowledge in the fields of art history and conservation, and the development of new patterns of explanation. For more information contact [email protected] All chapters of this book are available for download at courtauld.ac.uk/research/courtauld-books-online. Every effort has been made to contact the copyright holders of images reproduced in this publication. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. All rights reserved. Designed by Matthew Cheale Cover Image: Detail of Fig. 10.1, London, The British Museum, Inv. -

An Extraordinary and Very Rare Collection of Eight

AN EXTRAORDINARY AND VERY RARE COLLECTION OF EIGHT IVORY MICROCARVINGS SCULPTURES An Extraordinary and very rare Collection of eight Ivory Microcarvings Sculptures Ivory comes from the tusks of elephants, but it can also be obtained from other animals, such as walruses or mammoths. According to Margarita Estella, the ivory size and quality, i.e., its hardness, consistency and brightness depend on its place of origin and on the animal from which it is derived; and, let’s admit it, the animal will soon die without its defenses. The color ranges between bright white and yellowish, sometimes slightly pink, shades. Protected from ambient air, ivory perfectly maintains its original white. The physical qualities of ivory have attracted man since prehistoric times: its soft luster, its smooth feel and rich texture showed it as the ideal material for performing beautiful works. While miniature ivory carving has its origin in East Asia, microscopic-sized works did not emerge in the East but in Europe, which would obtain ivory through eastern Mediterranean ports, particularly from India, Sri Lanka and Africa. The best-known ivory carving workshops were located in southern Germany, and also in Switzerland and in France. These pieces show the rococo taste for what was unusual, rare, in this case for what was tiny, small-sized and delicate. The few artists specializing in microcarvings, proud that their works were immune to plagiarism, enjoyed the widespread demand by art studio owners and by treasury chambers. Maria Theresa, Catherine the Great and King George III, for example, owned some of these works. Microsculptures were created only from 1770 to the late eighteenth century. -

THE IVORY TRADE of LAOS: NOW the FASTEST GROWING in the WORLD LUCY VIGNE and ESMOND MARTIN

THE IVORY TRADE OF LAOS: NOW THE FASTEST GROWING IN THE WORLD LUCY VIGNE and ESMOND MARTIN THE IVORY TRADE OF LAOS: NOW THE FASTEST GROWING IN THE WORLD LUCY VIGNE and ESMOND MARTIN SAVE THE ELEPHANTS PO Box 54667 Nairobi 00200 သࠥ ⦄ Kenya 2017 © Lucy Vigne and Esmond Martin, 2017 All rights reserved ISBN 978-9966-107-83-1 Front cover: In Laos, the capital Vientiane had the largest number of ivory items for sale. Title page: These pendants are typical of items preferred by Chinese buyers of ivory in Laos. Back cover: Vendors selling ivory in Laos usually did not appreciate the displays in their shops being photographed. Photographs: Lucy Vigne: Front cover, title page, pages 6, 8–23, 26–54, 56–68, 71–77, 80, back cover Esmond Martin: Page 24 Anonymous: Page 25 Published by: Save the Elephants, PO Box 54667, Nairobi 00200, Kenya Contents 07 Executive summary 09 Introduction to the ivory trade in Laos 09 History 11 Background 13 Legislation 15 Economy 17 Past studies 19 Methodology for fieldwork in late 2016 21 Results of the survey 21 Sources and wholesale prices of raw ivory in 2016 27 Ivory carving in 2016 33 Retail outlets selling worked ivory in late 2016 33 Vientiane 33 History and background 34 Retail outlets, ivory items for sale and prices 37 Customers and vendors 41 Dansavanh Nam Ngum Resort 41 History and background 42 Retail outlets, ivory items for sale and prices 43 Customers and vendors 44 Savannakhet 45 Ivory in Pakse 47 Luang Prabang 47 History and background 48 Retail outlets, ivory items for sale and prices 50 Customers -

Secular Gothic Ivory

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of Arts and Architecture TACTILE PLEASURES: SECULAR GOTHIC IVORY A Dissertation in Art History by Katherine Elisabeth Staab © 2014 Katherine Elisabeth Staab Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2014 ii The dissertation of Katherine Elisabeth Staab was reviewed and approved* by the following: Elizabeth Bradford Smith Associate Professor of Art History Dissertation Adviser Chair of Committee Brian Curran Professor of Art History Charlotte M. Houghton Associate Professor of Art History Kathryn Salzer Assistant Professor of History Craig Zabel Associate Professor of Art History Head of the Department of Art History *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School. iii ABSTRACT This study approaches secular Gothic ivory mirror cases from the fourteenth century. Even more specifically, it considers scenes of so-called “romance” or “courtly” couples, which were often given as love pledges and used as engagement presents.1 There has been a recent flourishing of art historical interest in materiality and visual culture, focusing on the production, distribution, consumption, and significance of objects in everyday life, and my examination adds to that body of work.2 My purpose is not to provide a survey, history, or chronology of these objects, but rather to highlight one important, yet little-studied aspect. My dissertation situates the sensation of touch in the context of a wider understanding of the relationship between -

A Late Antique Ivory Plaque and Modern Response Dale Kinney Bryn Mawr College, [email protected]

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College History of Art Faculty Research and Scholarship History of Art 1994 A Late Antique Ivory Plaque and Modern Response Dale Kinney Bryn Mawr College, [email protected] Anthony Cutler Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.brynmawr.edu/hart_pubs Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Custom Citation Kinney, Dale, and Anthony Cutler. "A Late Antique Ivory Plaque and Modern Response." American Journal of Archaeology 98 (1994): 457-480. This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. http://repository.brynmawr.edu/hart_pubs/31 For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Late Antique Ivory Plaque and Modern Response DALE KINNEY Abstract "the" forger implicitly denies the historical relativity A recently published challenge to the authenticity of of aesthetics [not to mention style], and with it a the of the now in the Victoria ivory plaque Symmachi, fundamental premise of art history), Eisenberg's es- and Albert Museum, is refuted, and its late fourth-cen- say elicited a chorus of approbation from art profes- tury origin is confirmed by comparison with other sionals who plaques whose fourth- or fifth-century date is secure. wrote to express their own rejection of The charge of forgery is related to patterns in recent the object. Alan Shestack confessed that he had been art historiography,and these are traced to an anachro- "duped for decades" but was now converted; Chris- nistic critical that entails vocabulary inappropriate toph Clairmont proclaimed that "the forgery of the norms of illusionistic depiction. -

The South and South East Asian Ivory Markets. (2002)

© Esmond Martin and Daniel Stiles, March 2002 All rights reserved ISBN No. 9966-9683-2-6 Front cover photograph: These three antique ivory figurines of a reclining Buddha (about 50 cm long) with two praying monks were for sale in Bangkok for USD 34,000 in March 2001. Photo credit: Chryssee Martin Published by Save the Elephants, PO Box 54667, Nairobi, Kenya and 7 New Square, Lincoln’s Inn, London WC2A 3RA, United Kingdom. Printed by Majestic Printing Works Ltd., PO Box 42466, Nairobi, Kenya. Acknowledgements Esmond Martin and Daniel Stiles would like to thank Save the Elephants for their support of this project. They are also grateful to Damian Aspinall, Friends of Howletts and Port Lympne, The Phipps Foundation and one nonymous donor for their financial contributions without which the field-work in Asia would not have been possible. Seven referees — lain Douglas-Hamilton, Holly Dublin, Richard Lair, Charles McDougal, Tom Milliken, Chris Thouless and Hunter Weiler — read all or parts of the manuscript and made valuable corrections and contributions. Their time and effort working on the manuscript are very much appreciated. Thanks are also due to Gabby de Souza who produced the maps, and Andrew Kamiti for the excellent drawings. Chryssee Martin assisted with the field-work in Thailand and also with the report which was most helpful. Special gratitude is conveyed to Lucy Vigne for helping to prepare and compile the report and for all her help from the beginning of the project to the end. The South and South East Asian Ivory Markets Esmond Martin and Daniel Stiles Drawings by Andrew Kamiti Published by Save the Elephants PO Box 54667 c/o Ambrose Appelbe Nairobi 7 New Square, Lincoln’s Inn Kenya London WC2A 3RA 2002 ISBN 9966-9683-2-6 1 Contents List of Tables.................................................................................................................................... -

Ichiro: a Life's Work of Netsuke the Huey Shelton Collection

UNIVERSITY OF WYOMING ART MUSEUM 2009 Ichiro: A Life’s Work of Netsuke The Huey Shelton Collection PURPOSE OF THIS PACKET: EXPLORE: To provide K-12 teachers with background Students are encouraged to examine the various information on the exhibitions and suggest age professions, animals, and activities depicted in the appropriate applications for exploring concepts, netsuke carvings. What does the choice of subject say meaning, and artistic intent of work exhibited, before, about what is valued in the Japanese culture? during, and after the museum visit. CURRICULAR UNIT TopIC: CREATE: To examine netsuke sculptures as a means of artistic Students will be given time to create. They will sketch, and cultural expression. The focus of this educational draw, or sculpt a design for a netsuke that reflects the packet and curricular unit is to observe, question, student’s individual culture. explore, create, and reflect. OBSERVE: REFLECT: Students and teachers will observe the examples of Students will discuss their finished artwork with the netsuke carvings from master Netsuke carver Ichiro. other students and teachers and write a reflective paper Students will make comparisons between the different about the process they used to complete their work. styles and subject matter of netsuke. QUESTION: Students will have the opportunity to discuss the Japanese art form of netsuke. What are netsuke? What is the purpose? What materials are used? How do the netsuke carvings depict Japanese life? Ichiro Inada (Japanese, 1891-1977), Elderly Samurai Standing Pensively, Not dated, Ivory, 1-1/4 x 7/8 x 1 inches, The Huey G. and Phyllis T. -

FINE JAPANESE ART Thursday 17 May 2018

FINE JAPANESE ART Thursday 17 May 2018 SPECIALIST AND AUCTION ENQUIRIES LONDON Suzannah Yip Yoko Chino Masami Yamada NEW YORK Jeff Olson Takako O’Grady SENIOR CONSULTANTS Neil Davey Joe Earle FINE JAPANESE ART Thursday 17 May 2018 at 11am and 2.30pm 101 New Bond Street, London VIEWING ENQUIRIES CUSTOMER SERVICES Please see page 2 for bidder Saturday 12 May, Specialist, Head of Department Monday to Friday 8.30am to 6pm information including after-sale 11am to 5pm Suzannah Yip +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 collection and shipment Sunday 13 May, +44 (0) 20 7468 8368 11am to 5pm [email protected] Physical Condition of Lots in For the sole purpose of providing Monday 14 May, this Auction estimates in three currencies in 9am to 4.30pm Cataloguer the catalogue the conversion Tuesday 15 May, Yoko Chino PLEASE NOTE THAT THERE has been made at the exchange 9am to 4.30pm +44 (0) 20 7468 8372 IS NO REFERENCE IN THIS rate of approx. Wednesday 16 May, [email protected] CATALOGUE TO THE PHYSICAL £1: ¥151.1804 9am to 4.30pm CONDITION OF ANY LOT. £1: USD1.4100 Department Assistant INTENDING BIDDERS MUST Please note that this rate may SALE NUMBER Masami Yamada SATISFY THEMSELVES AS TO well have changed at the date 24680 +44 (0) 20 7468 8217 THE CONDITION OF ANY LOT of the auction. [email protected] AS SPECIFIED IN CLAUSE 15 CATALOGUE OF THE NOTICE TO BIDDERS お 品 物 のコン ディション につ いて £25.00 Senior Consultants CONTAINED AT THE END OF Neil Davey THIS CATALOGUE. -

Gothic Ivory Sculpture Content and Context

GOTHIC IVORY SCULPTURE CONTENT AND CONTEXT EDITED BY CATHERINE YVARD Gothic Ivory Sculpture: Content and Context Edited by Catherine Yvard With contributions by: Elisabeth Antoine-König Katherine Eve Baker Camille Broucke Jack Hartnell Franz Kirchweger Juliette Levy-Hinstin Christian Nikolaus Opitz Stephen Perkinson Naomi Speakman Michele Tomasi Catherine Yvard Series Editor: Alixe Bovey Managing Editor: Maria Mileeva Courtauld Books Online is published by the Research Forum of The Courtauld Institute of Art Somerset House, Strand, London WC2R 0RN © 2017, The Courtauld Institute of Art, London. ISBN: 978-1-907485-09-1. Courtauld Books Online is a series of scholarly books published by The Courtauld Institute of Art. The series includes research publications that emerge from Courtauld Research Forum events and Courtauld projects involving an array of outstanding scholars from art history and conservation across the world. It is an open-access series, freely available to readers to read online and to download without charge. The series has been developed in the context of research priorities of The Courtauld which emphasise the extension of knowledge in the fields of art history and conservation, and the development of new patterns of explanation. For more information contact [email protected] All chapters of this book are available for download at courtauld.ac.uk/research/courtauld-books-online. Every effort has been made to contact the copyright holders of images reproduced in this publication. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. All rights reserved. Designed by Matthew Cheale Cover Image: Detail of Fig. 10.1, London, The British Museum, Inv.