Three Ngarrindjeri Autobiographies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aboriginal Agency, Institutionalisation and Survival

2q' t '9à ABORIGINAL AGENCY, INSTITUTIONALISATION AND PEGGY BROCK B. A. (Hons) Universit¡r of Adelaide Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History/Geography, University of Adelaide March f99f ll TAT}LE OF CONTENTS ii LIST OF TAE}LES AND MAPS iii SUMMARY iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . vii ABBREVIATIONS ix C}IAPTER ONE. INTRODUCTION I CFIAPTER TWO. TI{E HISTORICAL CONTEXT IN SOUTH AUSTRALIA 32 CHAPTER THREE. POONINDIE: HOME AWAY FROM COUNTRY 46 POONINDIE: AN trSTä,TILISHED COMMUNITY AND ITS DESTRUCTION 83 KOONIBBA: REFUGE FOR TI{E PEOPLE OF THE VI/EST COAST r22 CFIAPTER SIX. KOONIBBA: INSTITUTIONAL UPHtrAVAL AND ADJUSTMENT t70 C}IAPTER SEVEN. DISPERSAL OF KOONIBBA PEOPLE AND THE END OF TI{E MISSION ERA T98 CTIAPTER EIGHT. SURVTVAL WITHOUT INSTITUTIONALISATION236 C}IAPTER NINtr. NEPABUNNA: THtr MISSION FACTOR 268 CFIAPTER TEN. AE}ORIGINAL AGENCY, INSTITUTIONALISATION AND SURVTVAL 299 BIBLIOGRAPI{Y 320 ltt TABLES AND MAPS Table I L7 Table 2 128 Poonindie location map opposite 54 Poonindie land tenure map f 876 opposite 114 Poonindie land tenure map f 896 opposite r14 Koonibba location map opposite L27 Location of Adnyamathanha campsites in relation to pastoral station homesteads opposite 252 Map of North Flinders Ranges I93O opposite 269 lv SUMMARY The institutionalisation of Aborigines on missions and government stations has dominated Aboriginal-non-Aboriginal relations. Institutionalisation of Aborigines, under the guise of assimilation and protection policies, was only abandoned in.the lg7Os. It is therefore important to understand the implications of these policies for Aborigines and Australian society in general. I investigate the affect of institutionalisation on Aborigines, questioning the assumption tl.at they were passive victims forced onto missions and government stations and kept there as virtual prisoners. -

Stretch Reconciliation Action Plan

Reconciliation Action Plan 2018 – 2020 Underwater Garden by Timeisha Simpson Timeisha Simpson is an emerging artist from Port Lincoln who has exhibited both on the West Coast and in Adelaide. She was studying in Year 9 when she created this work as part of Port Lincoln High School’s (PLHS) Aboriginal Arts Program. The PLHS Arts Program is an outlet for young artists to express themselves creatively. Local artist Jenny Silver has been working with the Arts Program for some time and has built strong relationships with all of the participating young artists. Many of the art works produced explore connections with culture, identity, family and place. It provides opportunities for the artists to be part of exhibitions across the state and their success at these exhibitions has created positive discussions with the wider community. An important aspect of the program is the emphasis on enterprise and the creation of individual artist portfolios. Jenny worked with Timeisha to create Underwater Garden, an acrylic painting that celebrates the richness and health of the water around Port Lincoln. Both artists spend a lot of time in the ocean and chose seaweed to represent growth and movement. Timeisha and Jenny developed authentic relationships with the community while on country which was integral in initial ideation for this piece. Timeisha says, ”The painting celebrates all the different bright coloured seaweeds in the ocean, I see these seaweeds when I go diving, snorkelling and fishing at the Port Lincoln National Park with my friends and family. I really enjoy going to Engine Point because that is where we go diving and snorkelling off the rocks, and for fishing we go to Salmon Hole and other cliff areas”. -

Rare Books Lib

RBTH 2239 RARE BOOKS LIB. S The University of Sydney Copyright and use of this thesis This thesis must be used in accordance with the provisions of the Copynght Act 1968. Reproduction of material protected by copyright may be an infringement of copyright and copyright owners may be entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. Section 51 (2) of the Copyright Act permits an authorized officer of a university library or archives to provide a copy (by communication or otherwise) of an unpublished thesis kept in the library or archives, to a person who satisfies the authorized officer that he or she requires the reproduction for the purposes of research or study. The Copyright Act gran~s the creator of a work a number of moral rights, specifically the right of attribution, the right against false attribution and the right of integrity. You may infringe the author's moral rights if you: • fail to acknowledge the author of this thesis if you quote sections from the work • attribute this thesis to another author • subject this thesis to derogatory treatment which may prejudice the author's reputation For further information contact the University's Director of Copyright Services Telephone: 02 9351 2991 e-mail: [email protected] Camels, Ships and Trains: Translation Across the 'Indian Archipelago,' 1860- 1930 Samia Khatun A thesis submitted in fuUUment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History, University of Sydney March 2012 I Abstract In this thesis I pose the questions: What if historians of the Australian region began to read materials that are not in English? What places become visible beyond the territorial definitions of British settler colony and 'White Australia'? What past geographies could we reconstruct through historical prose? From the 1860s there emerged a circuit of camels, ships and trains connecting Australian deserts to the Indian Ocean world and British Indian ports. -

Restoring Identity

restoring identity Final report of the Moving forward consultation project Amanda Cornwall Public Interest Advocacy Centre 2009 Copyright © Public Interest Advocacy Centre Ltd (PIAC), June 2009 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior permission. First published 2002 by PIAC Revised edition June 2009 by PIAC ISBN 978 0 9757934 5 9 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The Public Interest Advocacy Centre (PIAC) would like to thank all of the people who participated in focus group meetings and made submissions as part of the project. We appreciate that for many people it is difficult to talk about the past and how it affects their lives today. We thank the members of the reference group for their support and hard work during the original project: Elizabeth Evatt, PIAC’s Chairperson; Audrey Kinnear, Co-Person of the National Sorry Day Committee; Brian Butler, ATSIC Social Justice Commission; Harold Furber, Northern Territory stolen generations groups; and Dr William Jonas, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner, HREOC. PIAC would like to thank Darren Dick, Chris Cunneen, Reg Graycar and Jennifer Clarke who provided comments on the draft report in 2002 and Tom Poulton, Bianca Locsin and Chris Govey, of Allens Arthur Robinson, who provided pro bono assistance in drafting the Stolen Generations Reparations Bill that appears as Appendix 4 of this revised edition. Cover Image: National Painting of the Stolen Generation by Joy Haynes Editor: Catherine Page Design: Gadfly Media Enquiries to: Public Interest Advocacy Centre Ltd ABN 77 002 773 524 Level 9, 299 Elizabeth Street Sydney NSW 2000 AUSTRALIA Telephone: (02) 8898 6500 Facsimile: (02) 8898 6555 E-mail: [email protected] www.piac.asn.au Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are warned that this publication may contain references to deceased persons. -

'There's a Wall There—And That Wall Is Higher from Our Side'

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article ‘There’s a Wall There—And That Wall Is Higher from Our Side’: Drawing on Qualitative Interviews to Improve Indigenous Australians’ Experiences of Dental Health Services Skye Krichauff, Joanne Hedges and Lisa Jamieson * Dental School, University of Adelaide, Adelaide 5005, Australia; skye.krichauff@adelaide.edu.au (S.K.); [email protected] (J.H.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 5 August 2020; Accepted: 3 September 2020; Published: 7 September 2020 Abstract: Indigenous Australians experience high levels of untreated dental disease compared to non-Indigenous Australians. We sought to gain insight into barriers that prevent Indigenous Australians from seeking timely and preventive dental care. A qualitative study design was implemented, using face-to-face interviews conducted December 2019 to February 2020. Participants were 20 Indigenous Australians (10 women and 10 men) representing six South Australian Indigenous groups; Ngarrindjeri, Narungga, Kaurna, Ngadjuri, Wiramu, and Adnyamathanha. Age range was middle-aged to elderly. The setting was participants’ homes or workplaces. The main outcome measures were barriers and enablers to accessing timely and appropriate dental care. The findings were broadly grouped into eight domains: (1) fear of dentists; (2) confusion regarding availability of dental services; (3) difficulties making dental appointments; (4) waiting times; (5) attitudes and empathy of dental health service staff; (6) cultural friendliness of dental health service space; (7) availability of public transport and parking costs; and (8) ease of access to dental clinic. The findings indicate that many of the barriers to Indigenous people accessing timely and appropriate dental care may be easily remedied. -

National Sorry Day

COMMENT Issue No.5 May 1998 National Sorry Day Coming to terms with the past and present National Sorry Day is to be held on the 26th May, exactly one year after the tabling in Federal Parliament of Bringing Them Home – the report into the separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from their families. Bringing Them Home revealed the extent and devastating effects of the forced removal of Aboriginal children from their families - an official government policy that went on for 150 years into the early 1970s. The report proposed a number of recommendations including the establishment of ‘Sorry Day’. Other recommendations included the need for apologies, reparation, compensation, services for those affected, and action to ensure that current welfare and juvenile justice systems cease replicating the forced removal of Aboriginal children from their families and communities. This publication has been put together by Dulwich Centre Publications for National Sorry Day. It has been created out of our own desire to apologise to those Indigenous Australians whom we have so wronged and our hope that a publication would be helpful in facilitating discussions. We hope this publication can contribute to the movement of everyday non-Indigenous Australians who are seeking ways to come to terms with this country’s history, to heal past wrongs and address present injustices. Contents: Apologies to Indigenous Australia 2 Experiences of the enquiry into the Stolen Generation: ‘Coming home’ by Jane Lester 3 ‘Sorry as sharing sorrow’ by Sir -

Stolen Generations

the Stolen Generations south australian education pack For the pain, suffering and hurt of these Stolen Generations, their descendants and for their families left behind, we say sorry. To the mothers “and the fathers, the brothers and the sisters, for the breaking up of families and communities, we say sorry. And for the indignity and degradation thus inflicted on a proud people and a proud culture, we say sorry. Prime Minister Kevin Rudd, 13 February 2008 ” INTRODUCTION “ We cannot move forward until the legacies of the past are properly dealt with. This means acknowledging the truth of history, providing justice and allowing the process of healing to occur. We are not just talking here of the brutality of a time gone by - though that was certainly a shameful reality. We are talking of the present, of the ways in which the legacy of the past lives on for every single Aboriginal person and their families. It is time for non-Indigenous Australians to turn their reflective gaze inwards. It is time to look at non-Indigenous privilege - and to ask the question: ‘What was the cost of this advantage - and who paid the price?’ As former Governor-General, Sir William Deane, said in 1996: ‘Where there is no room for national pride or national shame about the past, there can be no national soul.’ …Only by understanding the truth of our past can we find a way to go forward. For the past permeates the present. The past shapes the present. The past is not past. …Encouraging reflection on the past is not intended to promote a wallowing in guilt. -

Reconciliation Action Plan 2018 – 2020 Contents

Reconciliation Action Plan 2018 – 2020 Contents RAP Artwork .............................................. 2 Welcomes ................................................ 4 Our Vision for Reconciliation .......................... 6 Our Business .............................................. 7 2014 - 2017 RAP Journey Highlights .................. 8 Case studies ............................................. 12 Relationships ............................................ 16 Respect .................................................. 20 Opportunities ........................................... 25 Tracking progress and reporting ...................... 27 Underwater Garden by Timeisha Simpson Timeisha Simpson is an emerging artist from Port Lincoln who has exhibited both on the West Coast and in Adelaide. She was studying in Year 9 when she created this work as part of Port Lincoln High School’s (PLHS) Aboriginal Arts Program. The PLHS Arts Program is an outlet for young artists to express themselves creatively. Local artist Jenny Silver has been working with the Arts Program for some time and has built strong relationships with all of the participating young artists. Many of the art works produced explore connections with culture, identity, family and place. It provides opportunities for the artists to be part of exhibitions across the state and their success at these exhibitions has created positive discussions with the wider community. An important aspect of the program is the emphasis on enterprise and the creation of individual artist portfolios. -

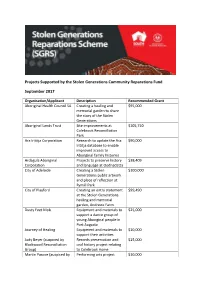

Projects Supported by the Stolen Generations Community Reparations Fund

Projects Supported by the Stolen Generations Community Reparations Fund September 2017 Organisation/Applicant Description Recommended Grant Aboriginal Health Council SA Creating a healing and $95,000 memorial garden to share the story of the Stolen Generations Aboriginal Lands Trust Site improvements at $105,750 Colebrook Reconciliation Park Ara Irititja Corporation Research to update the Ara $90,000 Irititja database to enable improved access to Aboriginal family histories Ardagula Aboriginal Projects to preserve history $38,409 Corporation and language at Oodnadatta City of Adelaide Creating a Stolen $100,000 Generations public artwork and place of reflection at Rymill Park City of Playford Creating an entry statement $99,490 at the Stolen Generations healing and memorial garden, Andrews Farm Dusty Feet Mob Equipment and materials to $25,000 support a dance group of young Aboriginal people in Port Augusta Journey of Healing Equipment and materials to $10,000 support their activities Judy Beyer (auspiced by Records preservation and $15,000 Blackwood Reconciliation oral history project relating Group) to Colebrook Home Martin Pascoe (auspiced by Performing arts project $10,000 Catholic Education SA) relating to Stolen Generations Marula Aboriginal Preserving and making $100,000 Corporation (auspiced by accessible records, Cultural Partnerships) photographs, stories and cultural information of the Wangkangarru Yuarluyandi people in far north-east South Australia Murray Bridge High School Oral histories of Stolen $92,202 Generations Nexus -

My-Ngarrindjeri-Calling-Index.Pdf (Pdf, 292.35

Kartinyeri Index Index ABC, 86 Aboriginal of the Year, 159–60 Life Matters program, 144 Aboriginality, proof of, 111 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Aborigines’ Friends Association, 9 Commission (ATSIC), 111, 151 Aborigines’ Protection Board, Aboriginal Family History Unit, see Protector of Aborigines see South Australian Museum, abortions, 155, 185 Doreen’s employment at Adelaide City Baths, 55 Aboriginal Health Agency, 116 Adelaide jail, 126 Aboriginal Heritage Act 1988, 43–4, Adelaide Review, 178–9 45, 152, 187 Adelaide University, see University Aboriginal Heritage Branch, 130–1 of Adelaide Aboriginal Housing Authority, 111 Adelaide Zoo, 78 Aboriginal Legal Rights Movement The Advertiser, 140, 165, 173 (ALRM/Legal Rights), 153, article on Doreen’s Honorary 157–8, 161 Doctorate, 172 Chapmans’ compensation case articles on remains found at lawyers, 196, 198, 202 Hindmarsh Island, 201–3 Charles, Chris, 26, 169 article on Una and Pat Rigney, 73 Doreen’s statement to Professor cartoon on ‘Politicians’ business’, Saunders, 67 167–8 Layton, Robyn, 169–70 interviews with Doreen, 43–4, Native Title Act meeting, 47 159–60 Native Title Unit, 135, 188, 194 James, Colin, 157–8, 168, 177 Royal Commission and Royal photos of Grandfather Gordon, Commission period, 175, 180, 183 122 Woolley Tim, 1, 26, 159; at Mount Agius, Josie, 137 House meeting, 150 Agius, Aunty Laura, 123 see also Fergie, Dr Deane; Saunders, Agius, Parry, 188 Sandra Agius, Rhonda, 158, 170 212 www.aboriginalstudiespress.com Kartinyeri Index Index agriculture, 19–20, 98, -

2009 SA Women's Honour Roll

Acknowledging and celebrating South Australian women in all their diversity. 2009 SOUTH AUSTRALIAN [women’s honour roll] SOUTH AUSTRALIAN [women’s honour roll] 2009 A message from the Hon Gail Gago MLC Minister for the Status of Women Congratulations to the 100 outstanding women selected for inclusion in the 2009 South Australian Women’s Honour Roll. The Honour Roll acknowledges and celebrates passionate and committed women who have made a positive contribution to the community. The Women’s Honour Roll was one way of achieving this member Kupa Piti Kungka Tjuta established in 2008 and I am very recognition. Coober Pedy Senior Aboriginal pleased that in 2009 over 250 Women’s Council, are highlighted Too often, women are silent South Australian women have for their extraordinary contributions achievers, and this year a been nominated - over 100 more to South Australia. concerted effort has been made to than last year. acknowledge women who have The 2009 Women’s Honour Roll It is vital that we find ways to not generally been publicly also pays posthumous tribute to recognise and celebrate the congratulated. women whose legacy remains achievements of women who strong and relevant today. This year, ten nominations have contribute so much to our been identified for special community. I hope that this Honour recognition. This inspiring group of Hon Gail Gago MLC Roll will continue to be just women, which includes the seven Minister for the Status for Women Office for Women acknowledges the Department of the Premier and Cabinet Aboriginal Affairs and Reconciliation Division for their support and assistance in providing information on the Elders and Aunties who have passed away. -

Special List Index for GRG52/90

Special List GRG52/90 Newspaper cuttings relating to aboriginal matters This series contains seven volumes of newspaper clippings, predominantly from metropolitan and regional South Australian newspapers although some interstate and national newspapers are also included, especially in later years. Articles relate to individuals as well as a wide range of issues affecting Aboriginals including citizenship, achievement, sport, art, culture, education, assimilation, living conditions, pay equality, discrimination, crime, and Aboriginal rights. Language used within articles reflects attitudes of the time. Please note that the newspaper clippings contain names and images of deceased persons which some readers may find distressing. Series date range 1918 to 1970 Index date range 1918 to 1970 Series contents Newspaper cuttings, arranged chronologically Index contents Arranged chronologically Special List | GRG52/90 | 12 April 2021 | Page 1 How to view the records Use the index to locate an article that you are interested in reading. At this stage you may like to check whether a digitised copy of the article is available to view through Trove. Articles post-1954 are unlikely to be found online via Trove. If you would like to view the record(s) in our Research Centre, please visit our Research Centre web page to book an appointment and order the records. You may also request a digital copy (fees may apply) through our Online Enquiry Form. Agency responsible: Aboriginal Affairs and Reconciliation Access Determination: Open Note: While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of special lists, some errors may have occurred during the transcription and conversion processes. It is best to both search and browse the lists as surnames and first names may also have been recorded in the registers using a range of spellings.