Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How the Vision of the Serampore Quartet Has Come Full Circle

Oxford Centre for Christianity and Culture, Centre for Baptist History and Heritage and Baptist Historical Society The heritage of Serampore College and the future of mission From the Enlightenment to modern missions: how the vision of the Serampore Quartet has come full circle John R Hudson 20 October 2018 The vision of the Serampore Quartet was an eighteenth century Enlightenment vision involving openness to ideas and respect for others and based on the idea that, for full understanding, you need to study both the ‘book of nature’ and the ‘book of God.’ Serampore College was a key component in the working out of this wider vision. This vision was superseded in Britain by the racist view that European civilisa- tion is superior and that Christianity is the means to bring civilisation to native peoples. This view had appalling consequences for native peoples across the Empire and, though some Christians challenged it, only in the second half of the twentieth century did Christians begin to embrace a vision more respectful of non-European cultures and to return to a view of the relationship between missionaries and native peoples more akin to that adopted by the Serampore Quartet. 1 Introduction Serampore College was not set up in 1818 as a theological college though ministerial training was to be part of its work (Carey et al., 1819); nor was it a major part, though it remains the most visible legacy of, the work of the Serampore Quartet.1 Rather it came as an outgrowth of the wider vision of the Serampore Quartet — a wider vision which, I will argue, arose from the eighteenth century Enlightenment and which has been rediscovered as the basis for mission in the second half of the twentieth century. -

People's Experience Towards Divyabhaskar Newspaper in Surat

Volume : 2 | Issue : 2 | february 2013 ISSN - 2250-1991 Research Paper Management People’s Experience Towards Divyabhaskar Newspaper in Surat City *Jigna Solanki * * B-21, Haridhan Society, Cross Road, Amroli-394107, Surat, Gujarat,India. ABSTRACT ‘Newspapers have always been a source of information and news for all the ages. The new media has expanded the horizons for news and information gatherers, but the focus of this study remainsNewspaper. This survey is designed to find out about divyabhaskar Newspapers liking. With reading news paper of divyabhaskar people are satisfied or not and what they want from the Newspaper. NewspapersAs carry vital information that are not available on any other information sources, therefore in this paper it will find out what are theople pe ‘s preference of getting news details Newspapers of other information sources. In this paper it will also try to find out the impact ofese th divyabhaskar Newspaper readership. Keywords: Newspapers, readership, media Introduction: tion in urban areas read English-language newspapers, com- The Industry Printing is a process for reproducing text and pared to a readership of only 0.3% of the population in the image, typically with ink on paper using a printing press. It is rural areas. often carried out as a large-scale industrial process, and is an essential part of publishing and transaction printing. There are two basic sources of revenue for the newspapers: 1. Advertising: Indian print media is one of the largest print media in the The bonus of making a profit after all costs- is on the ad world. The history of it started in 1780, with the publication of vertising revenue. -

DANIELLS Artists and Travellers

,···.:.:.:::.::.;.:·::;'.:.:J<" .J THE DANIELLS Artists and Travellers by THOMAS SUTTON F.S.A. LONDON • THE BODLEY HEAD VIEW OF THE CASCADE Engr4vtil 1111J coloureil by William 'D4n1itll .from 4 pai11ti11g by Captain &btrt Smith •.=. THE DANIELLS IN NORTHERN INDIA: 1. CALCUTTA TO DELHI 27 been endowed with literary talents commensurate with his widoubted artistic ability, he could have been the creator of one of the most absorbing travel diaries ofall times. To the art historian the diaries are of the greatest interest, crowded as they are with Chapter Two references to the methods used by his wide and himself. We find, for example, that they used the camera obscura, and in this they were probably by no means alone. There are various types of this mechanical aid and the type used by the Daniells was probably The Daniells in Northern the one shaped like a box, with an open side over which a curtain is hwig. By means of optical refraction (as in a reflex camera) the object to be depicted is reflected on a India - I sheet of paper laid on the base of the box. The artist can then readily trace with a pencil over the outlines of the reflected surface. Holbein is reputed to have used a mechanical Calcutta to Delhi : 1788-1789 device for the recording ofhis portraits of the Court ofHenry VIII, and other kinds of artistic aids were widoubtedly known from the rime ofDiircr onwards. It must not be imagined, however, that the result of tracing in the camera produces a finished picture. accurate itinerary of the wanderings of the Dani ells in India between 1788 and It is one thing to make a tracing, and quite another to make a work of art. -

Copyright © 2019 Matthew Marvin Reynolds All Rights Reserved. the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary Has Permission To

Copyright © 2019 Matthew Marvin Reynolds All rights reserved. The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary has permission to reproduce and disseminate this document in any form by any means for purposes chosen by the Seminary, including, without limitation, preservation or instruction. THE SPIRITUALITY OF WILLIAM WARD __________________ A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary __________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy __________________ by Matthew Marvin Reynolds May 2019 APPROVAL SHEET THE SPIRITUALITY OF WILLIAM WARD Matthew Marvin Reynolds Read and Approved by: __________________________________________ Michael A. G. Haykin (Chair) __________________________________________ Thomas J. Nettles __________________________________________ Joseph C. Harrod Date______________________________ I dedicate this dissertation to God, my Father in Christ. From its inception, it has felt that this endeavor has hung on a thread. But time and time again, God has orchestrated circumstances in just such a way as to make continued progress—and ultimately completion possible. To Him be all the glory. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................................... vii PREFACE ........................................................................................................................ viii Chapter 1. INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................1 -

William Carey: Did You Know? Little-Known Or Remarkable Facts About William Carey

Issue 36: William Carey: 19th c. Missionary to India William Carey: Did You Know? Little-known or remarkable facts about William Carey Dr. R.E. Hedland is missionary lecturer for the Conservative Baptist Fellowship Mission Society in Mylapore, India. He is the author of The Mission of the Church in the World (Baker, 1991). William Carey translated the complete Bible into 6 languages, and portions into 29 others, yet he never attended the equivalent of high school or college. His work was so impressive, that in 1807, Brown University conferred a Doctor of Divinity degree on him. William Carey is often called the Father of Modern Protestant Missions. But the first European Protestant missionaries to Asia arrived almost a century before he did. By the time Carey established his mission community, there were thousands of Christians in a Pietist-led settlement in southern India. William Carey’s ministry sparked a new era in missions. One historian notes that his work is “a turning-point; it marks the entry of the English-speaking world on a large scale into the missionary enterprise—and it has been the English-speaking world which has provided four-fifths of the [Protestant] missionaries from the days of Carey until the present time.” Due to an illness, Carey lost most of his hair in his early twenties. He wore a wig for about ten more years in England, but on his way to India, he reportedly threw his wig in the ocean and never wore one again. This famous phrase is the best-known saying of William Carey, yet Carey never said it this way. -

Raja Ram Mohan Roy (1772 — 1833)

UNIT – II SOCIAL THINKERS RAJA RAM MOHAN ROY (1772 — 1833) Introduction: Raja Ram Mohan Roy was a great socio-religious reformer. He was born in a Brahmin family on 10th May, 1772 at Radhanagar, in Hoogly district of Bengal (now West Bengal). Ramakanto Roy was his father. His mother’s name was Tarini. He was one of the key personalities of “Bengal Renaissance”. He is known as the “Father of Indian Renaissance”. He re- introduced the Vedic philosophies, particularly the Vedanta from the ancient Hindu texts of Upanishads. He made a successful attempt to modernize the Indian society. Life Raja Ram Mohan Roy was born on 22 May 1772 in an orthodox Brahman family at Radhanagar in Bengal. Ram Mohan Roy’s early education included the study of Persian and Arabic at Patna where he read the Quran, the works of Sufi mystic poets and the Arabic translation of the works of Plato and Aristotle. In Benaras, he studied Sanskrit and read Vedas and Upnishads. Returning to his village, at the age of sixteen, he wrote a rational critique of Hindu idol worship. From 1803 to 1814, he worked for East India Company as the personal diwan first of Woodforde and then of Digby. In 1814, he resigned from his job and moved to Calcutta in order to devote his life to religious, social and political reforms. In November 1930, he sailed for England to be present there to counteract the possible nullification of the Act banning Sati. Ram Mohan Roy was given the title of ‘Raja’ by the titular Mughal Emperor of Delhi, Akbar II whose grievances the former was to present 1/5 before the British king. -

Daniell's and Ayton's 1813 Coastal Voyage from Land's End To

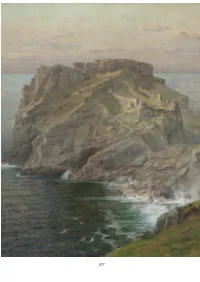

“Two Navigators…Sailing on Horseback”: Daniell’s and Ayton’s 1813 Coastal Voyage from Land’s End to Holyhead By Patrick D. Rasico Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in History May, 2015 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: James Epstein, Ph.D. Samira Sheikh, Ph.D. Peter Lake, Ph. D. Catherine Molineux, Ph.D. Humberto Garcia, Ph.D. 1 The othering of Welsh persons would remain a feature of English “home tour” travelogues throughout the nineteenth century. But in the English popular imaginary of the last decades of the eighteenth century, the Welsh landscape had begun to take on new meanings as a locus of picturesque topographical beauty. This was particularly true among visual artists. As early as 1770, the famed painter and aquatinter, Paul Sandby, made several tours through the Welsh countryside and produced multiple aquatint landscapes depicting the region.1 Sandby’s works opened the floodgate of tourists over the next decades. As Joseph Cradock avowed in 1777, “as everyone who has either traversed a steep mountain, or crossed a small channel, must write his Tour, it would be almost unpardonable in Me to be totally silent, who have visited the most uninhabited regions of North Wales.”2 The Wye Valley in Wales became the epicenter of British home tourism following the 1782 publication of William Gilpin’s Observations on the River Wye,3 one of the first English travel guides detailing the home tour.4 This treatise provided the initial conceptual framework of the picturesque topographical aesthetic. -

The Role of Christian Missionaries in Bengal

Bhatter College Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies Approved by the UGC (Serial No. 629, Subjects: Education, Broad category: Social Sciences) ISSN 2249-3301, Vol. VII, Number 1, 2017 Article url: www.bcjms.bhattercollege.ac.in/v7/n1/en-v7-01-07.pdf Article DOI: 10.25274/bcjms.v7n1.en-v7-01-07 The Genesis of English Education: the Role of Christian Missionaries in Bengal Thakurdas Jana Guest Lecturer, Department of English, Bhatter College, Dantan Abstract English Language Education has been an important factor for the uplift and development of an individual in this twenty first century when English is regarded as a lingua franca in the countries formerly colonized by the British. In every stratum of the society we need to learn English to have an easeful life. But the vernacular elementary education provided by the Pathsalas earlier was inadequate as observed by British observers like William Ward, William Adam and Francis Buchanan. In this situation, the Christian missionaries established many schools in West Bengal from 1819 onwards with the aim of providing western education to the mass of Bengal for their socio-cultural betterment. At that time Christian missionaries like Alexander Duff, William Carey, established many schools for providing English Education in and around Calcutta. Again George Pearce founded an English school at Durgapur in 1827. In the late 1820’s the missionaries achieved more success with the teaching of English. They made social and educational reform after Charter Act 1813 which permitted and financially helped them to spread English education in Bengal. This paper aims at unfolding the role played by those missionaries in spreading English education in Bengal. -

Historical Technological Impacts on the Visual Representation of Language with Reference to South Asian Typeforms

Historical technological impacts on the visual representation of language with reference to South Asian typeforms Article Accepted Version Ross, F. (2018) Historical technological impacts on the visual representation of language with reference to South Asian typeforms. Philological Encounters, 3 (4). ISSN 2451-9189 doi: https://doi.org/10.1163/24519197-12340054 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/66725/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . To link to this article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/24519197-12340054 Publisher: Brill All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online Fiona Ross Historical technological impacts on the visual representation of language with reference to South-Asian typeforms. The scripts of South Asia, which mainly derive from the Brahmi script, afford a visible voice to the numerous linguistic communities that form over one fifth of the world’s population. However, the transition of these visually diverse scripts from chirographic to typographic form has been determined by historical processes that were rarely conducive to accurately rendering non-Latin scripts. This essay provides a critical evaluation of the historical technological impacts on typographic textual composition in South-Asian languages. It draws on resources from relevant archival collections to consider within a historical context the technological constraints that have been crucial in determining the textural appearance of South-Asian typography. -

Modern Indian Responses to Religious Pluralism Author: Coward, Harold G

cover cover next page > title: Modern Indian Responses to Religious Pluralism author: Coward, Harold G. publisher: State University of New York Press isbn10 | asin: 0887065724 print isbn13: 9780887065729 ebook isbn13: 9780585089959 language: English subject Religious pluralism--India, Religious pluralism-- Hinduism. publication date: 1987 lcc: BL2015.R44M63 1987eb ddc: 291.1/72/0954 subject: Religious pluralism--India, Religious pluralism-- Hinduism. cover next page > If you like this book, buy it! file:///C:/...,%20Harold%20G.%20-%20Modern%20Indian%20Responses%20to%20Religious%20Pluralism/files/cover.html[26.08.2009 16:19:34] cover-0 < previous page cover-0 next page > Modern Indian Responses to Religious Pluralism Edited by Harold G. Coward State University of New York Press < previous page cover-0 next page > If you like this book, buy it! file:///C:/...20Harold%20G.%20-%20Modern%20Indian%20Responses%20to%20Religious%20Pluralism/files/cover-0.html[26.08.2009 16:19:36] cover-1 < previous page cover-1 next page > Published by State University of New York Press, Albany © 1987 State University of New York Printed in the United States of America No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address State University of New York Press, State University Plaza, Albany, N.Y., 12246 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Modern Indian responses to religious pluralism. Includes bibliographies -

The Yale Review of International Studies Table of Contents • Acheson Prize Issue 2019

The Yale Review of International Studies Table of Contents • Acheson Prize Issue 2019 19 Letter from Second Place: the Editor "Historical Elisabeth Mirrorism" Siegel Trinh Truong First Place: "Importing Arms, Exporting the Revolution" 38 Rosa Shapiro- Third Place: Thompson "A Transcript from Nature" 54 Oriana Tang Crossword Contest 56 Honorable Mention: "Developing 72 Socially Honorable Conscious Mention: Curricula "Reverse for Somali Cap-and- Schools" Trade for Refugees" Noora Reffat Jordan Farenhem 1 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Putt Punyagupta Andrew Song Elisabeth Siegel Staff Zhen Tu Will Waddingham MANAGING EDITORS Jake Mezey GRAPHIC DESIGN Qusay Omran Elisabeth Siegel Lauren Song ASST. MANAGING EDITOR Mary Orsak Max Krupnick Numi Katz Leila Iskandarani OUTREACH COORDINATORS STAFF Juanita Garcia Coco Chai Tyler Jager Chase Finney Leila Iskandarani SENIOR EDITORS Tasnim Islam Max Krupnick Henry Suckow-Ziemer Alayna Lee Muriel Wang Joon Lee Jack McCordick EDITORS Mary Orsak Katrina Starbird Jorge Familiar-Avalos Juanita Garcia Ariana Habibi CONTRIBUTORS Tyler Jager Jordan Farenhem Numi Katz Noora Reffat Brandon Lu Rosa Shapiro-Thompson Deena Mousa Oriana Tang Minahil Nawaz Trinh Truong Sam Pekats ACHESON PRIZE JUDGING PANEL Ana de la O Torres, Associate Professor of Political Science Isaiah Wilson (Colonal, U.S. Army, ret.), Senior Lecturer at the Jackson Institute for Global Affairs Clare Lockhart, Director and co-Founder of the Institute for State Effectiveness & Senior Fellow at the Jackson Institute for Global Affairs Julia Adams, Professor of Sociology and International and Area Studies & Head of Grace Hopper College 2 Dear Reader, You might notice that we look a little different. Welcome to the brand new YRIS redesign, arriving just in time for my favorite issue of the year: the Acheson Prize Issue. -

Analysis, Conclusions, Recommendations & Appendices

377 Chapter 5: Analysis of Results 378 CHAPTER 5 Analysis of Results 5.1. Introduction The coastal zones of England, Scotland and Wales are of enormous variety, scenic beauty and geomorphological interest on account of the wide range of geological exposures to be observed. The geological history, including the impacts of mountain building phases, have caused the rocks to be compressed, folded and faulted and, subsequently, they have been subjected to the processes of weathering and erosion over millions of years. Later, the impacts of glaciation and changes in sea level have led to the evolution and shaping of the coastline as we know it today. Over the last two centuries geologists, geographers and archaeologists have provided evidence of coastal change; this includes records of lost villages, coastal structures such as lighthouses, fortifications and churches, other important archaeological sites, as well as natural habitats. Some of these important assets have been lost or obscured through sea level rise or coastal erosion, whilst elsewhere, sea ports have been stranded from the coast following the accretion of extensive mudflats and saltmarshes. This ‘State of the British Coast’ study has sought to advance our understanding of the scale and rate of change affecting the physical, environmental and cultural heritage of coastal zones using artworks dating back to the 1770s. All those involved in coastal management have a requirement for high quality data and information including a thorough understanding of the physical processes at work around our coastlines. An appreciation of the impacts of past and potential evolutionary processes is fundamental if we are to understand and manage our coastlines in the most effective and sustainable way.