An Examination of Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles' "The Ih Story of Java" Natalie A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sir Stamford Raffles: Collecting in Southeast Asia

Press release Sir Stamford Raffles: collecting in Southeast Asia 1811-1824 19 September 2019 – 12 January 2020 High resolution images and caption sheet Free available at https://bit.ly/2lTvY5F Room 91 Supported by the Singapore High Commission Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles (1781 – 1826) spent most of his career as an East India Company official in Southeast Asia. He was appointed Lieutenant-Governor of Java in 1811 and assumed the Lieutenant Governor ship of Sumatra in 1818. Raffles is credited as being the founder of modern Singapore – but remains a controversial figure, particularly for his policies. When he was Lieutenant-Governor of Java, for example, he ordered troops to attack the most powerful court, which still has consequences to this day. Over time, he has been viewed as a scholarly expert on the region, a progressive reformer, a committed imperialist and an incompetent colonial official. He was also an avid collector of objects from the region, particularly amassing material from Java. He acquired objects to show his European audience that Javanese society was worth colonising. The exhibition will showcase an important selection of Hindu-Buddhist antiquities, different types of theatrical puppets, masks, musical instruments and stone and metal sculpture. Today, these objects provide us with a vital record of the art and court cultures of Java from approximately the 7th century to the early 19th century. Raffles’ collection was one of the first large gatherings of material from the region, providing us with a window into the wider worlds of Southeast Asia and Europe at the beginning of the 19th century. -

DANIELLS Artists and Travellers

,···.:.:.:::.::.;.:·::;'.:.:J<" .J THE DANIELLS Artists and Travellers by THOMAS SUTTON F.S.A. LONDON • THE BODLEY HEAD VIEW OF THE CASCADE Engr4vtil 1111J coloureil by William 'D4n1itll .from 4 pai11ti11g by Captain &btrt Smith •.=. THE DANIELLS IN NORTHERN INDIA: 1. CALCUTTA TO DELHI 27 been endowed with literary talents commensurate with his widoubted artistic ability, he could have been the creator of one of the most absorbing travel diaries ofall times. To the art historian the diaries are of the greatest interest, crowded as they are with Chapter Two references to the methods used by his wide and himself. We find, for example, that they used the camera obscura, and in this they were probably by no means alone. There are various types of this mechanical aid and the type used by the Daniells was probably The Daniells in Northern the one shaped like a box, with an open side over which a curtain is hwig. By means of optical refraction (as in a reflex camera) the object to be depicted is reflected on a India - I sheet of paper laid on the base of the box. The artist can then readily trace with a pencil over the outlines of the reflected surface. Holbein is reputed to have used a mechanical Calcutta to Delhi : 1788-1789 device for the recording ofhis portraits of the Court ofHenry VIII, and other kinds of artistic aids were widoubtedly known from the rime ofDiircr onwards. It must not be imagined, however, that the result of tracing in the camera produces a finished picture. accurate itinerary of the wanderings of the Dani ells in India between 1788 and It is one thing to make a tracing, and quite another to make a work of art. -

Daniell's and Ayton's 1813 Coastal Voyage from Land's End To

“Two Navigators…Sailing on Horseback”: Daniell’s and Ayton’s 1813 Coastal Voyage from Land’s End to Holyhead By Patrick D. Rasico Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in History May, 2015 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: James Epstein, Ph.D. Samira Sheikh, Ph.D. Peter Lake, Ph. D. Catherine Molineux, Ph.D. Humberto Garcia, Ph.D. 1 The othering of Welsh persons would remain a feature of English “home tour” travelogues throughout the nineteenth century. But in the English popular imaginary of the last decades of the eighteenth century, the Welsh landscape had begun to take on new meanings as a locus of picturesque topographical beauty. This was particularly true among visual artists. As early as 1770, the famed painter and aquatinter, Paul Sandby, made several tours through the Welsh countryside and produced multiple aquatint landscapes depicting the region.1 Sandby’s works opened the floodgate of tourists over the next decades. As Joseph Cradock avowed in 1777, “as everyone who has either traversed a steep mountain, or crossed a small channel, must write his Tour, it would be almost unpardonable in Me to be totally silent, who have visited the most uninhabited regions of North Wales.”2 The Wye Valley in Wales became the epicenter of British home tourism following the 1782 publication of William Gilpin’s Observations on the River Wye,3 one of the first English travel guides detailing the home tour.4 This treatise provided the initial conceptual framework of the picturesque topographical aesthetic. -

Koleksi Raffles Dari Jawa: Bukti Dari Eropa Tentang Sebuah Peradaban

PURBAWIDYA: Jurnal Penelitian dan Pengembangan Arkeologi p-ISSN: 2252-3758, e-ISSN: 2528-3618 ■ Terakreditasi Kementerian Ristekdikti No. 147/M/KPT/2020 Vol. 9 (2), November 2020, pp 165 – 182 ■ DOI: https://doi.org/10.24164/pw.v9i2.376 KOLEKSI RAFFLES DARI JAWA: BUKTI DARI EROPA TENTANG SEBUAH PERADABAN Raffles‘s Javan Collection: A European Proof of a Civilization Alexandra Green British Museum, Department of Asia, Great Russell Street, London WC1B 3DG, UK E-mail: [email protected] Naskah diterima: 16 Juli 2020 - Revisi terakhir: 30 September 2020 Disetujui terbit: 15 November 2020 - Tersedia secara online: 30 November 2020 Abstract Stamford Raffles was promoted to Lieutenant Governor of Java when the island was taken from the Dutch by the British East India Company in 1811 as part of the Napoleonic wars in Europe. During Raffles’ years on Java, he collected substantial cultural materials, among others are; theatrical objects, musical instruments, coins and amulets, metal sculpture, and drawings of Hindu- Buddhist buildings and sculpture. European interest in antiquities explains the ancient Hindu- Buddhist material in Raffles’s collection, but the theatrical objects were less understood easily. This essay explored Raffles’ s collecting practices, addressing the key questions of what he collected and why, as well as what were the shape of the collection can tell us about him, his ideas and beliefs, his contemporaries, and Java, including interactions between colonizers and locals. I compared the types of objects in the collections with Raffles’ writings, as well as the writings of his contemporaries on Java and Sumatra in the British Library and the Royal Asiatic Society. -

American Batik in the Early Twentieth Century Nicola J

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 1994 From Bohemian to Bourgeois: American Batik in the Early Twentieth Century Nicola J. Shilliam Museum of Fine Arts, Boston Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Materials Conservation Commons, Art Practice Commons, Fashion Design Commons, Fiber, Textile, and Weaving Arts Commons, Fine Arts Commons, and the Museum Studies Commons Shilliam, Nicola J., "From Bohemian to Bourgeois: American Batik in the Early Twentieth Century" (1994). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 1052. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/1052 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Shilliam, Nicola J. “From Bohemian to Bourgeois: American Batik in the Early Twentieth Century.” Contact, Crossover, Continuity: Proceedings of the Fourth Biennial Symposium of the Textile Society of America, September 22–24, 1994 (Los Angeles, CA: Textile Society of America, Inc., 1995). FROM BOHEMIAN TO BOURGEOIS: AMERICAN BATIK IN THE EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURY NICOLA J. SHILLIAM Assistant Curator, Textiles and Costumes, Museum of Fine Arts, 465 Huntington Avenue, Boston, MA 02115 In 1919 Pieter Mijer wrote in his influential book Batiks and How to Make Them: "Batik is still a comparatively recent importation; brought here some ten years ago, it was met with absolute incomprehension and lack of interest, but its real merit as a means of decorating fabrics has earned it a place in the industrial art of the nation and year by year it is gaining wider recognition. -

Imagineering Otherness: Anthropological

Imagineering otherness: anthropological legacies in contemporary tourism/Creando la imagineria de la alteridad: legados antropologicos en el turismo contemporaneo/Imagenhando alteridade: legados antropologicos no turismo contemporaneo Noel B. Salazar Anthropological Quarterly. 86.3 (Summer 2013): p669. Copyright: COPYRIGHT 2013 Institute for Ethnographic Research http://www.aq.gwu.edu/ Abstract: The role of anthropology as an academic discipline that seeds tourism imaginaries across the globe is more extensive than generally acknowledged. In this article, I draw on ethnographic and archival research in Indonesia and Tanzania to examine critically the recycling of long-refuted ethnological ideas and scientific ideologies in contemporary tourism interpretation. A fine-grained analysis of local tour guide narratives and practices in two popular destinations, Yogyakarta and Arusha, illustrates empirically how outdated scholarly models, including anthropological ones, are strategically used to represent and reproduce places and peoples as authentically different and relatively static, seemingly untouched by extra-local influences. [Keywords: Tourism, tour guiding, imagination, knowledge, representation, Indonesia, Tanzania] [Palabras clave: turismo, guias de turismo, imaginacion, conocimiento, representacion, Indonesia, Tanzania] [Palavras chave: Turismo, circuitos turisticos, imaginacao, conhecimento, representacao, Indonesia, Tanzania] Full Text: Although it could not be described as an academic anthropology, tourism developed a more popular -

Download an Explorer Guide +

SINGAPORE he Republic of Singa- Tpore is situated at the southern tip of peninsular Malaysia, only 85 miles (137 km) north of the equator. The Repub- lic consists of a tropical island of approximately 226 square miles (585 sq km) and some 54 smaller islets. An island of low undulating hills, Singapore reaches 26 miles (42 km) from west to east and extends 14 miles (22.5 km) from the Straits in the north to the island’s southern tip. This “city state” of approximately 4 million inhab- itants is a cosmopolitan community of Malay, Chinese (76% of the total), Indian and Eurasian races who enjoy the second highest standard HISTORY of living in Asia after Japan. Singapore is often Early records show that Malay sea gypsies and pirates were among the called the “Garden City” because of its attractive first to visit the island followed by Chinese traders. Colonists from Palem- green park like areas. It is a city of towering sky- bang in Sumatra arrived in 1287 and established a small fishing village. At scrapers, huge shopping complexes and vast various times this isolated sea port was controlled by the Sumatran Em- industrial estates. Its deepwater anchorage and pire of Srivijaya and the Cholas from South India. During this era the name natural harbor on the Straits of Malacca have was changed from Temasek (Sea Town) to Sing Pura, (City of the Lion). helped make it Southeast Asia’s largest port and This later evolved into Singapore and to this day the lion is a city symbol. one of the world’s greatest commercial centers. -

WHAT KILLED Sumatra), Where He Was Lieutenant- Governor

BICENTENNIAL OF SINGAPORE INSIGHT Introduction Sir Stamford Raffles (6 July 1781– 5 July 1826) landed in Singapore on 28 January 1819 when he was 37 years old.1 On 30 January that year, Raffles and the Temenggong (governor) for the Sultan of Johore signed a preliminary agreement to the establishment of a British trading post on the island. A week later, on 6 February, Raffles signed a treaty with Tunku Long declaring him to be the lawful sovereign of Johore and Singapore. This established him as Sultan Hussein Mohamed Shah. The treaty transferred the control of Singapore to the East India Company.2 While Raffles was setting up Singapore as a free port, his wife Sophia was pregnant and living in Penang. Raffles visited her on 13 February but the baby did not arrive and Raffles had to rush off to Acheen, Sumatra, to establish trading rights for this port. Sophia gave birth to a boy, Leopold Stamford, in the absence of the father.3 In the meantime, not only did Raffles establish Singapore as a trading port, but he also instituted the rule of law and laid the foundations of a city plan which was later executed by Philip Jackson.4 1 From 1820 to 1822, Raffles returned to British Bencoolen (Bengkulu City, WHAT KILLED Sumatra), where he was Lieutenant- Governor. During that time, his four children, all less than four years old, died of dysentery.3 Raffles returned to Singapore in 1823 where he established a school that was to become Raffles Institution.5 He also prohibited gambling, taxed alcohol and opium so as to discourage drunkenness and opium addiction, and banned slavery.6 During that year (1823), his wife gave birth to their fifth and only surviving Text by Dr Kenneth Lyen child. -

The Yale Review of International Studies Table of Contents • Acheson Prize Issue 2019

The Yale Review of International Studies Table of Contents • Acheson Prize Issue 2019 19 Letter from Second Place: the Editor "Historical Elisabeth Mirrorism" Siegel Trinh Truong First Place: "Importing Arms, Exporting the Revolution" 38 Rosa Shapiro- Third Place: Thompson "A Transcript from Nature" 54 Oriana Tang Crossword Contest 56 Honorable Mention: "Developing 72 Socially Honorable Conscious Mention: Curricula "Reverse for Somali Cap-and- Schools" Trade for Refugees" Noora Reffat Jordan Farenhem 1 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Putt Punyagupta Andrew Song Elisabeth Siegel Staff Zhen Tu Will Waddingham MANAGING EDITORS Jake Mezey GRAPHIC DESIGN Qusay Omran Elisabeth Siegel Lauren Song ASST. MANAGING EDITOR Mary Orsak Max Krupnick Numi Katz Leila Iskandarani OUTREACH COORDINATORS STAFF Juanita Garcia Coco Chai Tyler Jager Chase Finney Leila Iskandarani SENIOR EDITORS Tasnim Islam Max Krupnick Henry Suckow-Ziemer Alayna Lee Muriel Wang Joon Lee Jack McCordick EDITORS Mary Orsak Katrina Starbird Jorge Familiar-Avalos Juanita Garcia Ariana Habibi CONTRIBUTORS Tyler Jager Jordan Farenhem Numi Katz Noora Reffat Brandon Lu Rosa Shapiro-Thompson Deena Mousa Oriana Tang Minahil Nawaz Trinh Truong Sam Pekats ACHESON PRIZE JUDGING PANEL Ana de la O Torres, Associate Professor of Political Science Isaiah Wilson (Colonal, U.S. Army, ret.), Senior Lecturer at the Jackson Institute for Global Affairs Clare Lockhart, Director and co-Founder of the Institute for State Effectiveness & Senior Fellow at the Jackson Institute for Global Affairs Julia Adams, Professor of Sociology and International and Area Studies & Head of Grace Hopper College 2 Dear Reader, You might notice that we look a little different. Welcome to the brand new YRIS redesign, arriving just in time for my favorite issue of the year: the Acheson Prize Issue. -

The Kolkata (Calcutta) Stone

The Newsletter | No.74 | Summer 2016 4 | The Study The Kolkata (Calcutta) Stone The bicentennial of the British Interregnum in Java (1811-1816) provides the occasion to contemplate a lost opportunity to right some of the wrongs perpetrated by Sir Stamford Raffles and his light-fingered administration. Salient here is the fate of the two important stone inscriptions – the so-called ‘Minto’ (Sangguran) and ‘Kolkata’(Pucangan) stones – which chronicle the beginnings of the tenth-century Śailendra Dynasty in East Java and the early life of the celebrated eleventh-century Javanese king, Airlangga (1019-1049). Removed to Scotland and India respectively, the article assesses the historical importance of these two inscriptions and suggests ways in which their return might enhance Indonesia’s cultural heritage while strengthening ties between the three countries most intimately involved in Britain’s brief early nineteenth-century imperial moment in Java: India, Indonesia and the United Kingdom. Nigel Bullough and Peter Carey ON 4 AUGUST 1811, a 10,000-strong British expeditionary Above: Boats expectations have come to pass. There force, composed mainly of Indian troops (sepoys) principally from HM Sloop is seemingly no interest in the history from Bengal, but with a handful of specialist troops (horse Procris attacking of the short-lived British Interregnum in artillery and sappers) from the Madras (Chennai) Presidency and capturing six Java either on the part of the British or army, invaded Java to curb the expansionist plans in the Indian French gunboats off the Indonesians. This is strange indeed the coast of Java at Ocean of the Emperor Napoleon (reigned 1804-1814, 1815). -

1 Wayang in Museums

1 Wayang in Museums: The Reverse Repatriation of Javanese Puppets Matthew Isaac Cohen Puppets are theatrical devices or tools enabling the creation of dramatic characters in performances. Though inanimate objects, they are "given design, movement, and frequently, speech, in such a way that the audience imagines them to have life," as Steve Tillis states in his seminal overview of puppet theory.1 Puppets take on this semblance of life in a theatrical apparatus: posed in a tableau with other puppets, framed in a puppet booth or projected onto a shadow screen, situated in a narrative, interacting with music, shifting position, filled out or lifted up by a puppeteer's hand, and projecting outwards to spectators. A puppet is a "handy" object, in a Heideggerian sense--available, accessible, and ready for the trained puppeteer attuned to the puppet's affordances. At the same time, puppets possess agency in performance and behave in unpredictable ways. This was noted more than two decades ago by Bruno Latour, whose theories of the agency of objects and networks of humans and non-humans are increasingly informing puppetry scholarship. Latour observed that "[i]f you talk with a puppeteer, then you will find that he [sic] is perpetually surprised by his puppets. He makes the puppet do things that cannot be reduced to his action, and which he does not have the skill to do, even potentially. Is this fetishism? No, it is simply a recognition of the fact that we are exceeded by what we create."2 Puppetry as an art form thus serves "to induce an attentiveness to things and their affects," to draw on political philosopher Jane Bennett.3 By virtue of the puppet's liminal position as both bodily prosthesis and surprising object, puppetry can train what Bennet calls "a cultivated, patient, sensory attentiveness to nonhuman forces operating outside and inside the human body."4 The intimate bond between puppet and puppeteer is usually severed when puppets are accessioned by museums. -

Analysis, Conclusions, Recommendations & Appendices

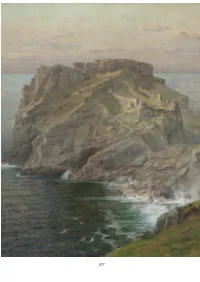

377 Chapter 5: Analysis of Results 378 CHAPTER 5 Analysis of Results 5.1. Introduction The coastal zones of England, Scotland and Wales are of enormous variety, scenic beauty and geomorphological interest on account of the wide range of geological exposures to be observed. The geological history, including the impacts of mountain building phases, have caused the rocks to be compressed, folded and faulted and, subsequently, they have been subjected to the processes of weathering and erosion over millions of years. Later, the impacts of glaciation and changes in sea level have led to the evolution and shaping of the coastline as we know it today. Over the last two centuries geologists, geographers and archaeologists have provided evidence of coastal change; this includes records of lost villages, coastal structures such as lighthouses, fortifications and churches, other important archaeological sites, as well as natural habitats. Some of these important assets have been lost or obscured through sea level rise or coastal erosion, whilst elsewhere, sea ports have been stranded from the coast following the accretion of extensive mudflats and saltmarshes. This ‘State of the British Coast’ study has sought to advance our understanding of the scale and rate of change affecting the physical, environmental and cultural heritage of coastal zones using artworks dating back to the 1770s. All those involved in coastal management have a requirement for high quality data and information including a thorough understanding of the physical processes at work around our coastlines. An appreciation of the impacts of past and potential evolutionary processes is fundamental if we are to understand and manage our coastlines in the most effective and sustainable way.