Daniell's and Ayton's 1813 Coastal Voyage from Land's End To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DANIELLS Artists and Travellers

,···.:.:.:::.::.;.:·::;'.:.:J<" .J THE DANIELLS Artists and Travellers by THOMAS SUTTON F.S.A. LONDON • THE BODLEY HEAD VIEW OF THE CASCADE Engr4vtil 1111J coloureil by William 'D4n1itll .from 4 pai11ti11g by Captain &btrt Smith •.=. THE DANIELLS IN NORTHERN INDIA: 1. CALCUTTA TO DELHI 27 been endowed with literary talents commensurate with his widoubted artistic ability, he could have been the creator of one of the most absorbing travel diaries ofall times. To the art historian the diaries are of the greatest interest, crowded as they are with Chapter Two references to the methods used by his wide and himself. We find, for example, that they used the camera obscura, and in this they were probably by no means alone. There are various types of this mechanical aid and the type used by the Daniells was probably The Daniells in Northern the one shaped like a box, with an open side over which a curtain is hwig. By means of optical refraction (as in a reflex camera) the object to be depicted is reflected on a India - I sheet of paper laid on the base of the box. The artist can then readily trace with a pencil over the outlines of the reflected surface. Holbein is reputed to have used a mechanical Calcutta to Delhi : 1788-1789 device for the recording ofhis portraits of the Court ofHenry VIII, and other kinds of artistic aids were widoubtedly known from the rime ofDiircr onwards. It must not be imagined, however, that the result of tracing in the camera produces a finished picture. accurate itinerary of the wanderings of the Dani ells in India between 1788 and It is one thing to make a tracing, and quite another to make a work of art. -

The Yale Review of International Studies Table of Contents • Acheson Prize Issue 2019

The Yale Review of International Studies Table of Contents • Acheson Prize Issue 2019 19 Letter from Second Place: the Editor "Historical Elisabeth Mirrorism" Siegel Trinh Truong First Place: "Importing Arms, Exporting the Revolution" 38 Rosa Shapiro- Third Place: Thompson "A Transcript from Nature" 54 Oriana Tang Crossword Contest 56 Honorable Mention: "Developing 72 Socially Honorable Conscious Mention: Curricula "Reverse for Somali Cap-and- Schools" Trade for Refugees" Noora Reffat Jordan Farenhem 1 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Putt Punyagupta Andrew Song Elisabeth Siegel Staff Zhen Tu Will Waddingham MANAGING EDITORS Jake Mezey GRAPHIC DESIGN Qusay Omran Elisabeth Siegel Lauren Song ASST. MANAGING EDITOR Mary Orsak Max Krupnick Numi Katz Leila Iskandarani OUTREACH COORDINATORS STAFF Juanita Garcia Coco Chai Tyler Jager Chase Finney Leila Iskandarani SENIOR EDITORS Tasnim Islam Max Krupnick Henry Suckow-Ziemer Alayna Lee Muriel Wang Joon Lee Jack McCordick EDITORS Mary Orsak Katrina Starbird Jorge Familiar-Avalos Juanita Garcia Ariana Habibi CONTRIBUTORS Tyler Jager Jordan Farenhem Numi Katz Noora Reffat Brandon Lu Rosa Shapiro-Thompson Deena Mousa Oriana Tang Minahil Nawaz Trinh Truong Sam Pekats ACHESON PRIZE JUDGING PANEL Ana de la O Torres, Associate Professor of Political Science Isaiah Wilson (Colonal, U.S. Army, ret.), Senior Lecturer at the Jackson Institute for Global Affairs Clare Lockhart, Director and co-Founder of the Institute for State Effectiveness & Senior Fellow at the Jackson Institute for Global Affairs Julia Adams, Professor of Sociology and International and Area Studies & Head of Grace Hopper College 2 Dear Reader, You might notice that we look a little different. Welcome to the brand new YRIS redesign, arriving just in time for my favorite issue of the year: the Acheson Prize Issue. -

Analysis, Conclusions, Recommendations & Appendices

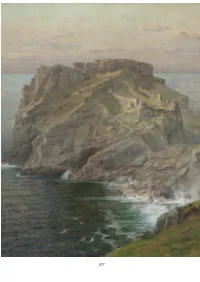

377 Chapter 5: Analysis of Results 378 CHAPTER 5 Analysis of Results 5.1. Introduction The coastal zones of England, Scotland and Wales are of enormous variety, scenic beauty and geomorphological interest on account of the wide range of geological exposures to be observed. The geological history, including the impacts of mountain building phases, have caused the rocks to be compressed, folded and faulted and, subsequently, they have been subjected to the processes of weathering and erosion over millions of years. Later, the impacts of glaciation and changes in sea level have led to the evolution and shaping of the coastline as we know it today. Over the last two centuries geologists, geographers and archaeologists have provided evidence of coastal change; this includes records of lost villages, coastal structures such as lighthouses, fortifications and churches, other important archaeological sites, as well as natural habitats. Some of these important assets have been lost or obscured through sea level rise or coastal erosion, whilst elsewhere, sea ports have been stranded from the coast following the accretion of extensive mudflats and saltmarshes. This ‘State of the British Coast’ study has sought to advance our understanding of the scale and rate of change affecting the physical, environmental and cultural heritage of coastal zones using artworks dating back to the 1770s. All those involved in coastal management have a requirement for high quality data and information including a thorough understanding of the physical processes at work around our coastlines. An appreciation of the impacts of past and potential evolutionary processes is fundamental if we are to understand and manage our coastlines in the most effective and sustainable way. -

The Picturesque and the Homogenisation of Empire

Volume y No. 1 The BRITISH AKT Journal The picturesque and the homogenisation of Empire Jeffrey Auerbach t is more than a century since JR Seeley remarked in The Expansion of England (1H83) that the British Empire Ideveloped in 'a fit of absence of mind'.' The rea,sons for and motives unt.lerlying its expansion, whether ptilitical. diplomatic, economic, social, intellectual, or religious, are fairly well known, however much they continue tt) be debated.- In recent years scholars have also begun to explore the impact of the empire on the so-called metropolitan centre. es[xrcially ¡politically.^ and have even questioned the ver\ boundaries between métropole and periphery' particularly in the cultural realni.^ Yet serious and fundamental questions remain about the place of the empire in the British mint!. How- did Britons conceive of and represent their empire, especially during the 19th century, the period of its greatest expansi()n? How did they come to regard it as being more unified than it actually was at the administrative level?^ What, if an>'thing, gave the empire coherence, especially in the half-century bef(ïre the steamship and the electric telegraph? How did the individual regions of the empire - 'one continent, a hundred peninsulas, five huntlred promontories, a thousand lakes, two thousand ri\'ers. ten thousand ¡.slands'"^» - become pan of an imperial whole? Viliat were the vectors of empire, and if, as man>' scholars have recently suggested, they should not be characterized in metre)["H)litan peripheral terms, then on what basis? The Victorian imagination constructed the British Enijiirc through a variety of cultural forms. -

Tales and Travels Drawings Recently Acquired on the Sunny Crawford Von Bülow Fund June 22 Through September 30, 2007

Tales and Travels Drawings Recently Acquired on the Sunny Crawford von Bülow Fund June 22 through September 30, 2007 Exhibition Labels Since her first gift in 1977—the insightful Portrait of Charles-Désiré Norry (1796–1818) by Jean-Auguste- Dominique Ingres—Sunny von Bülow, and more recently her daughter Cosima Pavoncelli, have made important acquisitions for the department of Drawings and Prints. During these three decades, they have substantially augmented the Morgan’s collection with eighty-two drawings and an album of sixty-four sheets. The selections for the Morgan were guided by a taste largely for eighteenth-century drawings and watercolors, although the chronological limits of the collection have recently expanded. The drawings presented here span three centuries and include several European schools. Despite this broad range, the group is particularly cohesive. Most of the drawings are highly finished, and many were made as independent works of art. This exhibition of the entire von Bülow collection, featuring thirty-seven new acquisitions since the first show of works acquired on the fund in 1995, commemorates the tremendous significance of the fund to the continued growth of the collection and honors the memory of Sunny von Bülow and her enduring and profoundly generous commitment to the Morgan. David Roberts (1796–1864) British Cairo, Looking West, 1839 Watercolor and gouache, over graphite Roberts was one of the first British artists to journey independently around Egypt, the Sinai, and the eastern Mediterranean. His views of Near Eastern cities and monuments were widely published in a series of lithographic prints. Roberts executed this sweeping panorama of Cairo during his six-week stay in the city from 1838 to 1839. -

“Daniells' Calcutta: Visions of Life, Death, and Nabobery in Late-Eighteenth-Century British India” by Patrick D. Rasico

“Daniells' Calcutta: Visions of Life, Death, and Nabobery in Late-Eighteenth-Century British India” By Patrick D. Rasico Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in History May, 2015 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: James Epstein, Ph.D. Samira Sheikh, Ph.D. Peter Lake, Ph. D. Catherine Molineux, Ph.D. Humberto Garcia, Ph.D. 1 Thomas Daniell and his nephew, William Daniell, left the British metropolis for South Asia in 1784 in order to refine their artistic abilities by observing and visually recording a distinctly “Indian picturesque” landscape aesthetic.1 They desired to capture exotic ecological and social matrixes by producing myriad topographical oil paintings and aquatint etchings while living in India.2 Most importantly, this uncle and nephew also composed countless sketches with camera obscura, charcoal and ink wash illustrations, and numerous notes and other studies during their travels throughout the subcontinent.3 (See images 1-2). In 1794, after nearly eight year in India,4 a worsening art market in Calcutta and recurrent ill health compelled the Daniells to return to Britain.5 Once back in England, the Daniells published many works featuring India’s interior. These painting and aquatints proved very popular among collectors and garnered the attention of artists and orientalist scholars.6 But these were not the only artworks of importance produced by the duo.7 This paper suggests that the aquatints composed and sold by Thomas and William Daniell during their time in residence in Calcutta have been greatly overlooked by scholars fixated upon the Daniells’ later images of India’s interior. -

A Picturesque Journey Through India 1786-1794

The Newsletter | No.61 | Autumn 2012 24 | The Focus: Swiss photographic collections on Asia A picturesque journey through India 1786-1794 Until recently, two large graphic portfolios containing 65 watercolours, each of respectable size, were part of the many unrecovered treasures of the St Gallen ethnographic collections. Their delicately and impressively painted motifs of the Orient, or more specifically, images of India, reflected the romantic style of the time, but the painters’ names, the dates of creation and their origins were at first a mystery. Roland Steffan 1 (left): Qutb-Minâr, near Delhi. Watercolour over pencil and ink (24 February 1789). Corresponding photograph shows site today. Due to the fact The watercolour collection in the collection. The collection allows for the observer tower were laid down by Qutb al Dîn Aibak in 1199, a former that the painters Pure coincidence and close scrutiny of the images helped to follow the almost forgotten meanderings of the English slave who became the founder of the first Muslim dynasty in had to rely on in identifying details. Whilst comparing each of the paintings, painters through India. Delhi. The watercolour was the first image of the Qutb-Minâr their Indian it became apparent that there were three distinctly differ- and the only image that shows the tower in its original state counterparts for ent artistic signatures. Further and more in-depth research India and the arts in the eighteenth century with the marble replacements of the top two stories, which the exact naming brought to light that most of the paintings in the portfolios Thomas Daniell and William Daniell were amongst the first had been added in 1368 after it had been hit by lightning. -

Martyn Gregory

REVEALING THE EAST • Cover illustration: no. 50 (detail) 2 REVEALING THE EAST Historical pictures by Chinese and Western artists 1750-1950 2 REVEALING THE EAST Historical pictures by Chinese and Western artists 1750-1950 MARTYN GREGORY CATALOGUE 91 2013-14 Martyn Gregory Gallery, 34 Bury Street, St. James’s, London SW1Y 6AU, UK tel (44) 20 7839 3731 fax (44) 20 7930 0812 email [email protected] www.martyngregory.com 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Our thanks are due to the following individuals who have generously assisted in the preparation of catalogue entries: Jeremy Fogg Susan Chen Hardy Andrew Lo Ken Phillips Eric Politzer Geoffrey Roome Roy Sit Kai Sin Paul Van Dyke Ming Wilson Frances Wilson 4 CONTENTS page Works by European and other artists 7 Works by Chinese artists 34 Works related to Burma (Myanmar) 81 5 6 PAINTINGS BY EUROPEAN AND OTHER ARTISTS 2. J. Barlow, 1771 1. Thomas Allom (1804-1872) A prospect of a Chinese village at the Island of Macao ‘Close of the attack on Shapoo, - the Suburbs on fire’ Pen and ink and grey wash, 5 ½ x 8 ins Pencil and sepia wash, 5 x 7 ½ ins Signed and dated ‘I Barlow 1771’, and inscribed as title Engraved by H. Adlard and published with the above title in George N. Wright, China, in a series of views…, 4 vols., 1843, vol. The author of this remarkably early drawing of Macau was III, opp. p.49 probably the ‘Mr Barlow’ who is recorded in the East India Company’s letter books: on 4 August 1771 he was given permission Thomas Allom’s detailed watercolour would probably have been by the Governor and Council of Fort St George, Madras (Chennai) redrawn from an eye-witness sketch supplied to him by one of to sail from there to Macau on the Company ship Horsendon (letter the officer-artists involved in the First Opium War, such as Lt received 22 Sep. -

An Examination of Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles' "The Ih Story of Java" Natalie A

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2005 Java as a Western construct: an examination of Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles' "The iH story of Java" Natalie A. Mault Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Mault, Natalie A., "Java as a Western construct: an examination of Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles' "The iH story of Java"" (2005). LSU Master's Theses. 3006. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/3006 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JAVA AS A WESTERN CONSTRUCT: AN EXAMINATION OF SIR THOMAS STAMFORD RAFFLES’ THE HISTORY OF JAVA A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The School of Art by Natalie A. Mault B.A., Knox College, 2001 December 2005 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my sincerest gratitude to the members of my thesis committee: Dr. Mark Zucker, for his guidance and knowledge, H. Parrott Bacot for his confidence in my abilities and contagious smile, and especially Dr. Darius A. Spieth, for the inspiration, constant encouragement, and for being someone I truly admire. I would also like to thank Professor Rick Ortner for his motivation, and Professor Jenna Kuttruff for all the time she spent working with me and for her extensive knowledge on textiles. -

Antiquarian Books 1617 August 2016

ANTIQUARIAN BOOKS 1617 AUGUST 2016 www.StoryLTD.com ANTIQUARIAN BOOKS Online Auction 16 17 August 2016 Bidding begins 8 pm IST on 16 August Viewings: 8 – 17 August 2016, 11 am – 7 pm, Monday – Saturday Sunday by appointment e gallery is closed for viewings on 15 August at Industry Manor, 3rd Floor, Appasaheb Marathe Marg Prabhadevi, Mumbai 400025 Contact : Aashish Dubey at 9819566483 Introducing our first ever auction of antiquarian books, this spectacular sale includes rare books from the 1700s to the early 20 th century. e selection features a spectrum of themes including, but not limited to, the British Raj and the Indian subcontinent. Many of these books include lavish colour illustrations by travellers to the subcontinent who recorded local subjects, sceneries and events as they witnessed them. is auction is conducted by Collectibles Antiques (India) Pvt. Ltd. and powered by StoryLTD. All lots in this sale are offered subject to the Conditions for Sale in the auction catalogue on storyltd.com. All lots are non-exportable. Bidders outside India can choose to pay in USD. However, they must enter a shipping address in India at the time of registration. e final price is inclusive of the buyer’s premium (calculated at 20% of the hammer price), and any applicable taxes. 1 TITLE OF VOLUME 1: A TITLE OF VOLUME 3: A COMPREHENSIVE HISTORY OF INDIA, COMPREHENSIVE HISTORY OF INDIA, CIVIL, MILITARY AND SOCIAL CIVIL, MILITARY AND SOCIAL SUB TITLE: From THE FIRST LANDING OF THE ENGLISH, SUB TITLE: From THE FIRST LANDING OF THE ENGLISH, To the Suppression of the Sepoy Revolt; including an To the Suppression of the Sepoy Revolt; including an outline of the early history of Hindoostan outline of the early history of Hindoostan VOLUME: 1 VOLUME: 3 AUTHOR: Henry Beveridge, Esq. -

Views of India Asian Art in London 2019

Views of India Asian Art in London 2019 Views of India 31st October - 9th November 2019 Please note that works will be sold on a first come first served basis and will be available from the moment the catalogue is distributed. Prices range from £200.00 - £30,000.00 Grosvenor Gallery 35 Bury Street London, SW1Y 6AY +44(0)20 7484 7979 [email protected] Rob Dean Art +44(0) 7764 942306 [email protected] 1. Emanuel Bowen 1694[?]–1767 A Map of India on the West Side of the Ganges Comprehending the Coasts of Malabar, Cormandel [sic.] and the Island Ceylon, Mid-18th century, hand coloured engraving on paper 33.5 x 24 cm, 13 1/4 x 9 1/2 in Emanuel Bowen was a British engraver and print seller. He was most well-known for his atlases and county maps. Although he died in poverty, he was widely acknowledged for his expertise and was appointed as mapmaker to both George II of England and Louis XV of France. £300.00 Of the great European artists working in India in the 18th and 19th Centuries it was undoubtedly the Daniells, Thomas (1749-1840) and his nephew William (1769-1837) who played a pre-eminent role in recording and documenting the country for European eyes. The aquatints of India by the Daniells have been continuously popular ever since their publication between 1795 and 1810. The British serving in India purchased them for their libraries or framed them for their houses, offices and clubs. In the early 19th century collectors eagerly acquired them as a celebration of the ‘sublime’, the ‘picturesque’ and the exotic as well as to record some of the recently documented antiquities of India. -

Proquest Dissertations

University of Alberta European Representations and Information Technologies in Early Nineteenth'Century India by Khyati Nagar © A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Humanities Computing Edmonton, Alberta Spring 2009 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-54617-8 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-54617-8 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Nnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation.