Rise & Fall of the Canton Trade System L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conceptualizing the Blue Frontier: the Great Qing and the Maritime World

Conceptualizing the Blue Frontier: The Great Qing and the Maritime World in the Long Eighteenth Century Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultüt der Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg Vorgelegt von Chung-yam PO Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Harald Fuess Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Joachim Kurtz Datum: 28 June 2013 Table of Contents Abstract 2 Acknowledgments 3 Emperors of the Qing Dynasty 5 Map of China Coast 6 Introduction 7 Chapter 1 Setting the Scene 43 Chapter 2 Modeling the Sea Space 62 Chapter 3 The Dragon Navy 109 Chapter 4 Maritime Customs Office 160 Chapter 5 Writing the Waves 210 Conclusion 247 Glossary 255 Bibliography 257 1 Abstract Most previous scholarship has asserted that the Qing Empire neglected the sea and underestimated the worldwide rise of Western powers in the long eighteenth century. By the time the British crushed the Chinese navy in the so-called Opium Wars, the country and its government were in a state of shock and incapable of quickly catching-up with Western Europe. In contrast with such a narrative, this dissertation shows that the Great Qing was in fact far more aware of global trends than has been commonly assumed. Against the backdrop of the long eighteenth century, the author explores the fundamental historical notions of the Chinese maritime world as a conceptual divide between an inner and an outer sea, whereby administrators, merchants, and intellectuals paid close and intense attention to coastal seawaters. Drawing on archival sources from China, Japan, Korea, Vietnam, and the West, the author argues that the connection between the Great Qing and the maritime world was complex and sophisticated. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. University M crct. rrs it'terrjt onai A Be" 4 Howe1 ir”?r'"a! Cor"ear-, J00 Norte CeeD Road App Artjor mi 4 6 ‘Og ' 346 USA 3 13 761-4’00 600 sC -0600 Order Number 9238197 Selected literary letters of Sophia Peabody Hawthorne, 1842-1853 Hurst, Nancy Luanne Jenkins, Ph.D. -

“The Silver Age”: Exhibiting Chinese Export Silverware in China Susan Eberhard

Concessions in “The Silver Age”: Exhibiting Chinese Export Silverware in China Susan Eberhard Introduction How do transcultural artifacts support global political agendas in post-socialist Chinese museums? In a 2018 state media photograph, a young woman gazes at a glittering silver compote, her fingertips pressed against the glass case.1 From an orthodox Chinese nationalist perspective on history, the photo of a visitor at The Silver Age: A Special Exhibition of Chinese Export Silver might present a vexing image of cultural consumption.2 “Chinese export silver” Zhongguo waixiao yinqi 中国外销銀器 is a twentieth-century collector’s term, translated from English, for objects sold by Chinese silverware and jewelry shops to Euro-American consumers.3 1 Xinhua News Agency, “Zhongguo waixiao yinqi liangxiang Shenyang gugong [China’s export silverware appears in Shenyang Palace Museum],” Xinhua中国外销银器 News February亮相沈阳故宫 6, 2018, accessed November 5, 2019, http://www.xinhuanet.com/photo/2018- 02/06/c_129807025_2.htm (photograph by Long Lei ). 龙雷 2 Chinese title: Baiyin shidai—Zhongguo waixiao yinqi tezhan . A compote is a fruit stand, or a shallow dish with a stemmed base.白银时代—中国外银銀器特 The exhibition catalogue describes展 the object as a “built-up and welded grapevine fruit dish” (duihan putaoteng guopan ) and in English, “compote with welded grapevine design.” See Wang Lihua 堆焊葡萄藤果盤, Baiyin shidai—Zhongguo waixiao yinqi tezhan [The王立华 Silver Age: A Special Exhibition of Chinese Export Silver]白银时代———中国外销银器特展 (Changsha: Hunan meishu chubanshe, 2017), 73. Unless otherwise noted, all translations are my own. The general introduction and section introductions of the exhibition and catalogue were bilingual, while the rest of the texts were only in Chinese; I have focused on the Chinese-language texts. -

Englischer Diplomat, Commissioner Chinese Maritime Customs Biographie 1901 James Acheson Ist Konsul Des Englischen Konsulats in Qiongzhou

Report Title - p. 1 of 348 Report Title Acheson, James (um 1901) : Englischer Diplomat, Commissioner Chinese Maritime Customs Biographie 1901 James Acheson ist Konsul des englischen Konsulats in Qiongzhou. [Qing1] Aglen, Francis Arthur = Aglen, Francis Arthur Sir (Scarborough, Yorkshire 1869-1932 Spital Perthshire) : Beamter Biographie 1888 Francis Arthur Aglen kommt in Beijing an. [ODNB] 1888-1894 Francis Arthur Aglen ist als Assistent für den Chinese Maritime Customs Service in Beijing, Xiamen (Fujian), Guangzhou (Guangdong) und Tianjin tätig. [CMC1,ODNB] 1894-1896 Francis Arthur Aglen ist Stellvertretender Kommissar des Inspektorats des Chinese Maritime Customs Service in Beijing. [CMC1] 1899-1903 Francis Arthur Aglen ist Kommissar des Chinese Maritime Customs Service in Nanjing. [ODNB,CMC1] 1900 Francis Arthur Aglen ist General-Inspektor des Chinese Maritime Customs Service in Shanghai. [ODNB] 1904-1906 Francis Arthur Aglen ist Chefsekretär des Chinese Maritime Customs Service in Beijing. [CMC1] 1907-1910 Francis Arthur Aglen ist Kommissar des Chinese Maritime Customs Service in Hankou (Hubei). [CMC1] 1910-1927 Francis Arthur Aglen ist zuerst Stellvertretender General-Inspektor, dann General-Inspektor des Chinese Maritime Customs Service in Beijing. [ODNB,CMC1] Almack, William (1811-1843) : Englischer Teehändler Bibliographie : Autor 1837 Almack, William. A journey to China from London in a sailing vessel in 1837. [Reise auf der Anna Robinson, Opiumkrieg, Shanghai, Hong Kong]. [Manuskript Cambridge University Library]. Alton, John Maurice d' (Liverpool vor 1883) : Inspektor Chinese Maritime Customs Biographie 1883 John Maurice d'Alton kommt in China an und dient in der chinesischen Navy im chinesisch-französischen Krieg. [Who2] 1885-1921 John Maurice d'Alton ist Chef Inspektor des Chinese Maritime Customs Service in Nanjing. -

Introduction

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-15066-9 - Global Trade in the Nineteenth Century: The House of Houqua and the Canton System John D. Wong Excerpt More information Introduction In the closing months of 1842, when the Qing court and the British government had just concluded the negotiations that ended the Opium War, the Chinese Hong merchant Wu Bingjian, known to his Western partners as Houqua,1 was already becoming immersed in the business of reactivating his trade network. On December 23, 1842, from his base in Canton, Houqua wrote to his American associates, John Murray Forbes and John’s brother Robert “Bennet” Forbes: “My dear friends, / I cannot let the Akbar go off without a few lines to you.” The ship the Akbar had served as a conduit for the frequent dispatch of messages and cargo between Houqua and his American partners. As the ship stood ready to return to America, Houqua prepared a note to acknowledge his receipt of letters from John and Bennet that another American associate, Mr. King, had interpreted for him. He had no time to respond to the particulars in these letters; however, he hurried to compose a quick message to accompany his shipment on the departing boat. “I send you by the Akbar about 500 tons of Teas all of good quality, & nearly all imported by myself from the Tea country. I have invoiced them low, & hope the result will be good.” Why the rush? Houqua had received market intelligence that the U.S. government might impose a heavy duty on tea imports, but that “ships leaving here [from Canton] before January may get their cargoes in free.” He limited his specific instructions to the brothers thus: “If a fair profit can be realized I am inclined to recommend early sales & returns, and with this remark for your consideration, the selling will be left to your discretion.” In the global tea market, speed was of the essence. -

Adopting a Chinese Mantle: Designing and Appropriating Chineseness 1750-1820

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ Adopting a Chinese Mantle Designing and Appropriating Chineseness 1750-1820 Newport, Emma Helen Henke Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 24. Sep. 2021 Adopting a Chinese Mantle: Designing and Appropriating Chineseness 1750-1820 Emma Helen Henke Newport King’s College London Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Research 1 Abstract The thesis examines methods of imagining and appropriating China in Britain in the period 1750 to 1820. -

Imperial China and the West Part I, 1815–1881

China and the Modern World: Imperial China and the West Part I, 1815–1881 The East India Company’s steamship Nemesis and other British ships engaging Chinese junks in the Second Battle of Chuenpi, 7 January 1841, during the first opium war. (British Library) ABOUT THE ARCHIVE China and the Modern World: Imperial China and the West Part I, 1815–1881 is digitised from the FO 17 series of British Foreign Office Files—Foreign Office: Political and Other Departments: General Correspondence before 1906, China— held at the National Archives, UK, providing a vast and significant primary source for researching every aspect of Chinese-British relations during the nineteenth century, ranging from diplomacy to trade, economics, politics, warfare, emigration, translation and law. This first part includes all content from FO 17 volumes 1–872. Source Library Number of Images The National Archives, UK Approximately 532,000 CONTENT From Lord Amherst’s mission at the start of the nineteenth century, through the trading monopoly of the Canton System, and the Opium Wars of 1839–1842 and 1856–1860, Britain and other foreign powers gradually gained commercial, legal, and territorial rights in China. Imperial China and the West provides correspondence from the Factories of Canton (modern Guangzhou) and from the missionaries and diplomats who entered China in the early nineteenth century, as well as from the envoys and missions sent to China from Britain and the later legation and consulates. The documents comprising this collection include communications to and from the British legation, first at Hong Kong and later at Peking, and British consuls at Shanghai, Amoy (Xiamen), Swatow (Shantou), Hankow (Hankou), Newchwang (Yingkou), Chefoo (Yantai), Formosa (Taiwan), and more. -

Houqua and His China Trade Partners in the Nineteenth Century

Global Positioning: Houqua and His China Trade Partners in the Nineteenth Century The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Wong, John. 2012. Global Positioning: Houqua and His China Trade Partners in the Nineteenth Century. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:9282867 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA © 2012 – John D. Wong All rights reserved. Professor Michael Szonyi John D. Wong Global Positioning: Houqua and his China Trade Partners in the Nineteenth Century Abstract This study unearths the lost world of early-nineteenth-century Canton. Known today as Guangzhou, this Chinese city witnessed the economic dynamism of global commerce until the demise of the Canton System in 1842. Records of its commercial vitality and global interactions faded only because we have allowed our image of old Canton to be clouded by China’s weakness beginning in the mid-1800s. By reviving this story of economic vibrancy, I restore the historical contingency at the juncture at which global commercial equilibrium unraveled with the collapse of the Canton system, and reshape our understanding of China’s subsequent economic experience. I explore this story of the China trade that helped shape the modern world through the lens of a single prominent merchant house and its leading figure, Wu Bingjian, known to the West by his trading name of Houqua. -

DANIELLS Artists and Travellers

,···.:.:.:::.::.;.:·::;'.:.:J<" .J THE DANIELLS Artists and Travellers by THOMAS SUTTON F.S.A. LONDON • THE BODLEY HEAD VIEW OF THE CASCADE Engr4vtil 1111J coloureil by William 'D4n1itll .from 4 pai11ti11g by Captain &btrt Smith •.=. THE DANIELLS IN NORTHERN INDIA: 1. CALCUTTA TO DELHI 27 been endowed with literary talents commensurate with his widoubted artistic ability, he could have been the creator of one of the most absorbing travel diaries ofall times. To the art historian the diaries are of the greatest interest, crowded as they are with Chapter Two references to the methods used by his wide and himself. We find, for example, that they used the camera obscura, and in this they were probably by no means alone. There are various types of this mechanical aid and the type used by the Daniells was probably The Daniells in Northern the one shaped like a box, with an open side over which a curtain is hwig. By means of optical refraction (as in a reflex camera) the object to be depicted is reflected on a India - I sheet of paper laid on the base of the box. The artist can then readily trace with a pencil over the outlines of the reflected surface. Holbein is reputed to have used a mechanical Calcutta to Delhi : 1788-1789 device for the recording ofhis portraits of the Court ofHenry VIII, and other kinds of artistic aids were widoubtedly known from the rime ofDiircr onwards. It must not be imagined, however, that the result of tracing in the camera produces a finished picture. accurate itinerary of the wanderings of the Dani ells in India between 1788 and It is one thing to make a tracing, and quite another to make a work of art. -

William Jardine (Merchant) from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

William Jardine (merchant) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia For other people with the same name see "William Jardine" (disambiguation) William Jardine (24 February 1784 – 27 February 1843) was a Scottish physician and merchant. He co-founded the Hong Kong conglomerate Jardine, Matheson and Company. From 1841 to 1843, he was Member of Parliament for Ashburton as a Whig. Educated in medicine at the University of Edinburgh, Jardine obtained a diploma from the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh in 1802. In the same year, he became a surgeon's mate aboard the Brunswick of the East India Company, bound for India. Captured by the French and shipwrecked in 1805, he was repatriated and returned to the East India Company's service as ship's surgeon. In May 1817, he left medicine for commerce.[1] Jardine was a resident in China from 1820 to 1839. His early success in Engraving by Thomas Goff Lupton Canton as a commercial agent for opium merchants in India led to his admission in 1825 as a partner of Magniac & Co., and by 1826 he was controlling that firm's Canton operations. James Matheson joined him shortly after, and Magniac & Co. was reconstituted as Jardine, Matheson & Co in 1832. After Imperial Commissioner Lin Zexu confiscated 20,000 cases of British-owned opium in 1839, Jardine arrived in London in September, and pressed Foreign Secretary Lord Palmerston for a forceful response.[1] Contents 1 Early life 2 Jardine, Matheson and Co. 3 Departure from China and breakdown of relations 4 War and the Chinese surrender Portrait by George Chinnery, 1820s 5 Death and legacy 6 Notes 7 See also 8 References 9 External links Early life Jardine, one of five children, was born in 1784 on a small farm near Lochmaben, Dumfriesshire, Scotland.[2] His father, Andrew Jardine, died when he was nine, leading the family in some economic difficulty. -

Mainland Hong Kong

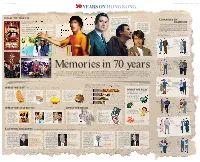

6 | Monday, October 21, 2019 HONG KONG EDITION | CHINA DAILY 7 In 1980, the Hong Kong TV series Wong Kar-wai’s fi lm, Days of Being Wild, played by Chow in 1990, brought Leslie Cheung his first Yun-fat, The Bund, Best Actor trophy in the Hong Kong Film Popular mainland TV dramas in HK swept up both Hong Awards. Along with many other classical and TVB rating rankings Kong and Chinese diverse screen images In the 1990s, Hong Kong mainland television he created, Cheung actor and director Stephen Fashion changes over time. But closer interaction and mutual infl u- Ye a r Drama Ranking In the ’70s, Hong Kong audiences with its remains one Chow gained fame through ence can be seen through ever-changing fashion styles of Hong Kong 2000 Records of Kangxi’s Travel Incognito 10 kung fu star Bruce Lee checkered plots and of the most his unconventional “silly and the mainland over the past 70 years. The two parallel fashion took Chinese martial arts powerful theme song. iconic actors talk” humor, earning him styles began to overlap in the 1970s when Hong Kong movies and TV 2006 The Return of the Condor Heroes 3 to Hollywood for the fi rst in the city’s the nickname dramas dominated the Chinese-speaking world. The interaction of the time. His movies gained movie “the king of two places grew much more intense under the impact of globalization 2015 The Empress of China 2 enormous success around history. comedy”. in the 21st century. 2018 Story of Yanxi Palace 1 the world. -

Samuel Russell Wadsworth House

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMBNo. 1024-0018 SAMUEL WADSWORTH RUSSELL HOUSE United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service_____________ National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Russell, Samuel Wadsworth, House Other Name/Site Number: Honors College, Wesleyan University 2. LOCATION Street & Number: 350 High Street Not for publication: N/A City/Town: Middletown Vicinity: N/A State: Connecticut County: Middlesex Code: 007 Zip Code: 06457 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s): X_ Public-Local: _ District: _ Public-State: _ Site: _ Public-Federal: Structure: _ Object: _ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 2 2 buildings _ _ sites _ _ structures _ _ objects 2 2 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 2 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: N/A NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 SAMUEL WADSWORTH RUSSELL HOUSE Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this __ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property __ meets __ does not meet the National Register Criteria.