Bai Xianyong in Translation: Wandering Through a Garden, Waking from a Dream

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adopting a Chinese Mantle: Designing and Appropriating Chineseness 1750-1820

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ Adopting a Chinese Mantle Designing and Appropriating Chineseness 1750-1820 Newport, Emma Helen Henke Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 24. Sep. 2021 Adopting a Chinese Mantle: Designing and Appropriating Chineseness 1750-1820 Emma Helen Henke Newport King’s College London Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Research 1 Abstract The thesis examines methods of imagining and appropriating China in Britain in the period 1750 to 1820. -

Mainland Hong Kong

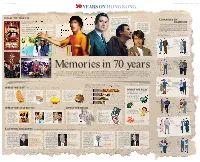

6 | Monday, October 21, 2019 HONG KONG EDITION | CHINA DAILY 7 In 1980, the Hong Kong TV series Wong Kar-wai’s fi lm, Days of Being Wild, played by Chow in 1990, brought Leslie Cheung his first Yun-fat, The Bund, Best Actor trophy in the Hong Kong Film Popular mainland TV dramas in HK swept up both Hong Awards. Along with many other classical and TVB rating rankings Kong and Chinese diverse screen images In the 1990s, Hong Kong mainland television he created, Cheung actor and director Stephen Fashion changes over time. But closer interaction and mutual infl u- Ye a r Drama Ranking In the ’70s, Hong Kong audiences with its remains one Chow gained fame through ence can be seen through ever-changing fashion styles of Hong Kong 2000 Records of Kangxi’s Travel Incognito 10 kung fu star Bruce Lee checkered plots and of the most his unconventional “silly and the mainland over the past 70 years. The two parallel fashion took Chinese martial arts powerful theme song. iconic actors talk” humor, earning him styles began to overlap in the 1970s when Hong Kong movies and TV 2006 The Return of the Condor Heroes 3 to Hollywood for the fi rst in the city’s the nickname dramas dominated the Chinese-speaking world. The interaction of the time. His movies gained movie “the king of two places grew much more intense under the impact of globalization 2015 The Empress of China 2 enormous success around history. comedy”. in the 21st century. 2018 Story of Yanxi Palace 1 the world. -

Chapter 2. Analysis of Korean TV Dramas

저작자표시-비영리-변경금지 2.0 대한민국 이용자는 아래의 조건을 따르는 경우에 한하여 자유롭게 l 이 저작물을 복제, 배포, 전송, 전시, 공연 및 방송할 수 있습니다. 다음과 같은 조건을 따라야 합니다: 저작자표시. 귀하는 원저작자를 표시하여야 합니다. 비영리. 귀하는 이 저작물을 영리 목적으로 이용할 수 없습니다. 변경금지. 귀하는 이 저작물을 개작, 변형 또는 가공할 수 없습니다. l 귀하는, 이 저작물의 재이용이나 배포의 경우, 이 저작물에 적용된 이용허락조건 을 명확하게 나타내어야 합니다. l 저작권자로부터 별도의 허가를 받으면 이러한 조건들은 적용되지 않습니다. 저작권법에 따른 이용자의 권리는 위의 내용에 의하여 영향을 받지 않습니다. 이것은 이용허락규약(Legal Code)을 이해하기 쉽게 요약한 것입니다. Disclaimer Master’s Thesis of International Studies The Comparison of Television Drama’s Production and Broadcast between Korea and China 중한 드라마의 제작 과 방송 비교 August 2019 Graduate School of International Studies Seoul National University Area Studies Sheng Tingyin The Comparison of Television Drama’s Production and Broadcast between Korea and China Professor Jeong Jong-Ho Submitting a master’s thesis of International Studies August 2019 Graduate School of International Studies Seoul National University International Area Studies Sheng Tingyin Confirming the master’s thesis written by Sheng Tingyin August 2019 Chair 박 태 균 (Seal) Vice Chair 한 영 혜 (Seal) Examiner 정 종 호 (Seal) Abstract Korean TV dramas, as important parts of the Korean Wave (Hallyu), are famous all over the world. China produces most TV dramas in the world. Both countries’ TV drama industries have their own advantages. In order to provide meaningful recommendations for drama production companies and TV stations, this paper analyzes, determines, and compares the characteristics of Korean and Chinese TV drama production and broadcasting. -

The United States and China: from Noncommunication to Diplomatic Relations

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 12-1979 The United States and China: From Noncommunication to Diplomatic Relations Mary Jeanne Patrick Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the International Law Commons, and the International Relations Commons Recommended Citation Patrick, Mary Jeanne, "The United States and China: From Noncommunication to Diplomatic Relations" (1979). Master's Theses. 2036. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/2036 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE UNITED STATES AND CHINA: FROM NONCOMMUNICATION TO DIPLOMATIC RELATIONS by Mary Jeanne Patrick A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the Degree of Master of Arts Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan December 1979 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. THE UNITED STATES AND CHINA: FROM NONCOMMUNICATION TO DIPLOMATIC RELATIONS Mary Jeanne Patrick, M.A. Western Michigan University, 1979 After more than two decades of fundamental differences due to lack of direct diplomatic relations, the People's Republic of China and the United States are developing a harmonious working relationship. Friendly relations between these two major nations began to improve in 1972 during President Richard Nixon's v is it to China that had been arranged by Henry Kissinger, Assistant for National Security Affairs. -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION This volume attempts to furnish to the reader of Chinese history in America. Where the original a history of the Chinese in California. It was writ• 49'er pioneer and his generation came as a so• ten to accommodate the many requests received journer, leaving behind, family, hearth and home, from educators assigned to present minority group the present newcomers come more as a family unit, culture and history in California public schools. as individuals determined to set their roots here. Although it is entitled A History of the Chinese Thus the disparity between sexes which once in California, the scope of its material embraces reached 27 males for each female, is also rapidly other areas as well. In a nineteenth century mobile becoming a page of the past. force mainly unencumbered by family, it was to The increased number of new immigrants is be expected that men would be continually on the causing much revision in the social, economic and move seeking to better their economic condition. political life of the Chinese in America. A new Thus, to illustrate, in pursuing the subject of the chapter of that history will unfold as newcomers fishing industry, it would be illogical to confine attempt to make the adjustments necessary to enter the material to California while ignoring their the mainstream of community life. Naturally their activities in Alaska. A good portion of that labor old-world customs, habits and outlooks will cling force consisted of California residents who an• to them until they adjust to the new environment. nually shipped out to Alaska to work in the can• Until then, such organizations as the Chinese fam• neries during the canning period. -

China and LA County, BYD Has Offices in Europe, Japan, South Korea, India, Taiwan, and Other Regions

GROWING TOGETHER China and Los Angeles County GROWING TOGETHER China and Los Angeles County PREPARED BY: Ferdinando Guerra, International Economist Principal Researcher and Author with special thanks to George Entis, Research Assistant June, 2014 Los Angeles County Economic Development Corporation Kyser Center for Economic Research 444 S. Flower St., 37th Floor Los Angeles, CA 90071 Tel: (213) 622-4300 or (888) 4-LAEDC-1 Fax: (213)-622-7100 E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.laedc.org The LAEDC, the region’s premier business leadership organization, is a private, non-profit 501(c)3 organization established in 1981. GROWING TOGETHER China and Los Angeles County As Southern California’s premier economic development organization, the mission of the LAEDC is to attract, retain, and grow businesses and jobs for the regions of Los Angeles County. Since 1996, the LAEDC has helped retain or attract more than 198,000 jobs, providing over $12 billion in direct economic impact from salaries and over $850 million in property and sales tax revenues to the County of Los Angeles. LAEDC is a private, non-profit 501(c)3 organization established in 1981. Regional Leadership The members of the LAEDC are civic leaders and ranking executives of the region’s leading public and private organizations. Through financial support and direct participation in the mission, programs, and public policy initiatives of the LAEDC, the members are committed to playing a decisive role in shaping the region’s economic future. Business Services The LAEDC’s Business Development and Assistance Program provides essential services to L.A. County businesses at no cost, including coordinating site searches, securing incentives and permits, and identifying traditional and nontraditional financing including industrial development bonds. -

Reflection of Feminism Development in Female-Centered Chinese TV Series

2020 International Conference on Educational Innovation and Philosophical Inquiries (ICEIPI 2020) Reflection of Feminism Development in Female-Centered Chinese TV Series Lin Mao1,a,* 1School of Social Work, Columbia University, 285 St. Nicholas Ave Apt 56, New York City, USA a. [email protected] *corresponding author Keywords: female representation, Chinese TV series, feminism Abstract: Female-centered TV series have been a trend in China in the past few years. It seems like the portray of those heroines have contributed to improving female representation through media and promoting feminism. However, the objectification of women still exists and is deep-rooted. This paper is going to look at how the changes in female-centered Chinese TV series reflected the changes in feminism and female representation in real life. The research finds that although the main theme of this kind of series have changed from pursuing love to pursuing career, female images were still represented as to be saved and innocent. 1. Introduction Female-centered TV series became a trend in China a few years ago. It is a form of TV shows that centered around the female lead and tell stories about her growth path (Wang, 2019). One of the most popular TV dramas in recent years, Story of Yanxi Palace (Yu, 2018), can be a representative. This form of TV series was a revolution because it was singular to narrate women’s stories on screen, and they engross female audiences immediately. For instance, the average audience measurement of Jade Palace Lock Heart (Yu, 2011), a TV series that was released in 2011, reached 2.52 and ranked in second place that year, and about 66.3% of audiences were female. -

The Background and Development of the 1871 Korean-American Incident: a Case Study in Cultural Conflict

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 5-17-1974 The background and development of the 1871 Korean-American incident: a case study in cultural conflict Robert Ray Swartout Jr Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Diplomatic History Commons, Military History Commons, and the United States History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Swartout, Robert Ray Jr, "The background and development of the 1871 Korean-American incident: a case study in cultural conflict" (1974). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 2424. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.2421 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS O:F Robert Hay Swartout, ,Jr. for the Master of Arts in History presented l\Iay 17, 197,1. Title: The Background and Development of the 1871 Korean-American Incident: A Case Study in Cultural Conflict APPROVED BY MEMBERS OF THE THESIS COMMITTEE: Berm::rd V. Burke '.Basu Dmytrys~"lyn This study is an attempt to combine the disciplines of Asian history and United States diplomatic history in analyzing the 1871 Korean-American Incident. The Incident revolves around the Low-Hodgers eA.-pedition to Korea, and the sub- sequent breakdown of peaceful negotiations into a military dash of arms. To describe the Incident as merely another example of American "im- perialism, '' or as a result of narrow-mindad Korean isolationism, is to over- simplify its causes and miss the larger implications that can be learned from it. -

U.S.-China Relations: a Brief Historical Perspective

U.S.-China Relations: A Brief Historical Perspective A Report by the U.S.-China Policy Foundation RELATIONS BEGIN 1784 Contact between the U.S. and China began in August 1784 when The Empress of China Empress of sailed to Guangzhou, a province in southern China. According to the U.S. Department of China State’s Office of the Historian, in the 18th century, all trade with Western nations was arrives in conducted through Guangzhou. 1784 “marked the new nation’s entrance into the Guangzhou lucrative China trade in tea, porcelain, and silk.” Other Americans arrived in China, but not until nearly fifty years later. The first American missionaries to arrive landed in Guangzhou in February 1830. On the ship were two protestant ministers, the Reverends Elijah Bridgman and David Abeel, sent by the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions. Before arriving, Bridgman had extensively studied Chinese culture and history. The first medical missionary was Dr. Peter Parker, who arrived in 1834 in, once again, Guangzhou. He established a small clinic in the foreign quarter, but with the large number of patients, he soon expanded in what would become the Guangzhou hospital. Chinese travelers arrived in the U.S. around the same time Americans arrived in China. In 1785, three Chinese sailors arrived in Baltimore, Maryland, stranded on shore by a trading ship. They arrived from Guangzhou, but there is no record of what happened to them after landing. Chinese culture and history first reached the U.S. in 1839 when a merchant from Philadelphia, who had spent 12 years trading with China, brought over a huge collection of art, artifacts, botanical samples, and more. -

Chinese Emperor Wang Mang Repealed His Reforms, Which Had Created Widespread Protest

THE CENTRAL KINGDOM, CONTINUED GO BACK TO THE PREVIOUS PERIOD HDT WHAT? INDEX THE CENTRAL KINGDOM CHINA 9 CE From this year into 23 CE, Wang Mang, a Confucian chief minister, would be emperor of China. The new emperor set free China’s slaves. “NARRATIVE HISTORY” AMOUNTS TO FABULATION, THE REAL STUFF BEING MERE CHRONOLOGY China “Stack of the Artist of Kouroo” Project HDT WHAT? INDEX CHINA THE CENTRAL KINGDOM 12 CE Germanicus Caesar became consul to the Emperor Augustus Caesar. From about this point until 15 CE, Annius Rufus would be the Roman Prefect of Iudaea (that is, of Samaria, Judea, and Idumea). The Chinese Emperor Wang Mang repealed his reforms, which had created widespread protest. Maybe freeing all slaves had not been such a hot idea, after all. HDT WHAT? INDEX THE CENTRAL KINGDOM CHINA 17 CE In China, there being more than one way to skin a cat, a tax was imposed upon the ownership of slaves. Hippalus, a Greek sea captain, discovered a method of employing monsoon winds in sailing, a finding that would open direct sea trade between the Eastern Mediterranean and India. SPICE “HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE” BEING A VIEW FROM A PARTICULAR POINT IN TIME (JUST AS THE PERSPECTIVE IN A PAINTING IS A VIEW FROM A PARTICULAR POINT IN SPACE), TO “LOOK AT THE COURSE OF HISTORY MORE GENERALLY” WOULD BE TO SACRIFICE PERSPECTIVE ALTOGETHER. THIS IS FANTASY-LAND, YOU’RE FOOLING YOURSELF. THERE CANNOT BE ANY SUCH THINGIE, AS SUCH A PERSPECTIVE. China “Stack of the Artist of Kouroo” Project HDT WHAT? INDEX CHINA THE CENTRAL KINGDOM 22 CE From this year until 220 CE, the later (Eastern) Han dynasty in China. -

The Evolution of British and American Images in China of the Taiping Rebels

ABSTRACT FROM REVERED REVOLUTIONARIES TO MUCH MALIGNED MARAUDERS: THE EVOLUTION OF BRITISH AND AMERICAN IMAGES IN CHINA OF THE TAIPING REBELS by Kapree Harrell-Washington The aim of this paper it to present the images of the Taipings, their leaders, and their ideologies as constructed by two of these powerful expatriate communities, Great Britain and the United States. It also explores the political, social, cultural and economic factors that contributed to the formation of these images. In order to properly construct and analyze these images, this paper appeals to a variety of primary and secondary sources including contemporary newspapers, magazines, books, memoirs, and foreign relations documents. FROM REVERED REVOLUTIONARIES TO MUCH MALIGNED MARAUDERS: THE EVOLUTION OF BRITISH AND AMERICAN IMAGES IN CHINA OF THE TAIPING REBELS A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History by Kapree Harrell-Washington Miami University Oxford Ohio 2008 Advisor David Fahey Reader Wenxi Liu Reader Amanda McVety Table of Contents Note on Names iii 1. Introduction 1 2. Great Britain and America in China before the Taiping Rebellion 4 Section 1: The British Experience 4 Section 2: The American Experience 11 3. Overview of the Taiping Rebellion 19 4. Early Images of the Taipings 30 Section 1: Nothing But a Band of Robbers 30 Section 2: A Period of Ambiguity: 1851 to 1853 34 5. Height of Popularity: Positive Images of the Taipings: 1853 to 1854 38 Section 1: The Construction of Positive Images 38 Section 2: The Chinese Protestants 44 Section 3: The Revolutionaries 49 Section 4: The “Civilized” Chinese 52 6. -

2015 BEAP Conference Proceedings

Conference Proceedings 2015 “Bald Eagle & Panda” U.S.-China Culture Exchange Virtual Conference November, 2015 Iowa State University of Science and Technology Ames, Iowa, USA Editors Linda Hagedorn, Ph.D. Liang (Rebecca) Tang, Ph.D. Arne Hallam, Ph.D. Editorial Notes What is the Bald Eagle and Panda Conference? The Bald Eagle and Panda Virtual Conference is an annual event, first began in 2014, funded by the U.S. Department of State and the U.S. Embassy in Beijing. The conference evolved through the collaboration between Iowa State University (ISU) in the U.S. and Henan Normal University (HNNU) in China. Since 2012, HNNU and ISU have worked together to establish an American Cultural Center on the HNNU campus that can enhance English language training, understanding American culture from a comparative perspective, and enriching curriculum across both universities for the creation of global citizens with wide perspectives and open minds. We seek to enhance critical thinking and open dialogue across the globe. The Bald Eagle and Panda (BEAP) Conference is preceded by a call for proposals asking students to submit a short essay (250-300 words) describing their intentions for a longer and more complete presentation and/or paper. All proposals were evaluated on the following: importance of the topic within American and Chinese cultural exchange, quality of writing, potential for effective display, and suitability/readiness for presentation. All students were given informative feedback on their proposals. Proposals were either accepted for presentation, accepted but not presented, or declined. Proposers in the first two categories were invited to submit a full paper that would be included in these proceedings and will enter them into the competition for prizes.