Adopting a Chinese Mantle: Designing and Appropriating Chineseness 1750-1820

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Constitutional Requirements for the Royal Morganatic Marriage

The Constitutional Requirements for the Royal Morganatic Marriage Benoît Pelletier* This article examines the constitutional Cet article analyse les implications implications, for Canada and the other members of the constitutionnelles, pour le Canada et les autres pays Commonwealth, of a morganatic marriage in the membres du Commonwealth, d’un mariage British royal family. The Germanic concept of morganatique au sein de la famille royale britannique. “morganatic marriage” refers to a legal union between Le concept de «mariage morganatique», d’origine a man of royal birth and a woman of lower status, with germanique, renvoie à une union légale entre un the condition that the wife does not assume a royal title homme de descendance royale et une femme de statut and any children are excluded from their father’s rank inférieur, à condition que cette dernière n’acquière pas or hereditary property. un titre royal, ou encore qu’aucun enfant issu de cette For such a union to be celebrated in the royal union n’accède au rang du père ni n’hérite de ses biens. family, the parliament of the United Kingdom would Afin qu’un tel mariage puisse être célébré dans la have to enact legislation. If such a law had the effect of famille royale, une loi doit être adoptée par le denying any children access to the throne, the laws of parlement du Royaume-Uni. Or si une telle loi devait succession would be altered, and according to the effectivement interdire l’accès au trône aux enfants du second paragraph of the preamble to the Statute of couple, les règles de succession seraient modifiées et il Westminster, the assent of the Canadian parliament and serait nécessaire, en vertu du deuxième paragraphe du the parliaments of the Commonwealth that recognize préambule du Statut de Westminster, d’obtenir le Queen Elizabeth II as their head of state would be consentement du Canada et des autres pays qui required. -

Entre Classicismo E Romantismo. Ensaios De Cultura E Literatura

Entre Classicismo e Romantismo. Ensaios de Cultura e Literatura Organização Jorge Bastos da Silva Maria Zulmira Castanheira Studies in Classicism and Romanticism 2 FLUP | CETAPS, 2013 Studies in Classicism and Romanticism 2 Studies in Classicism and Romanticism is an academic series published on- line by the Centre for English, Translation and Anglo-Portuguese Studies (CETAPS) and hosted by the central library of the Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do Porto, Portugal. Studies in Classicism and Romanticism has come into being as a result of the commitment of a group of scholars who are especially interested in English literature and culture from the mid-seventeenth to the mid- nineteenth century. The principal objective of the series is the publication in electronic format of monographs and collections of essays, either in English or in Portuguese, with no pre-established methodological framework, as well as the publication of relevant primary texts from the period c. 1650–c. 1850. Series Editors Jorge Bastos da Silva Maria Zulmira Castanheira Entre Classicismo e Romantismo. Ensaios de Cultura e Literatura Organização Jorge Bastos da Silva Maria Zulmira Castanheira Studies in Classicism and Romanticism 2 FLUP | CETAPS, 2013 Editorial 2 Sumário Apresentação 4 Maria Luísa Malato Borralho, “Metamorfoses do Soneto: Do «Classicismo» ao «Romantismo»” 5 Adelaide Meira Serras, “Science as the Enlightened Route to Paradise?” 29 Paula Rama-da-Silva, “Hogarth and the Role of Engraving in Eighteenth-Century London” 41 Patrícia Rodrigues, “The Importance of Study for Women and by Women: Hannah More’s Defence of Female Education as the Path to their Patriotic Contribution” 56 Maria Leonor Machado de Sousa, “Sugestões Portuguesas no Romantismo Inglês” 65 Maria Zulmira Castanheira, “O Papel Mediador da Imprensa Periódica na Divulgação da Cultura Britânica em Portugal ao Tempo do Romantismo (1836-1865): Matérias e Imagens” 76 João Paulo Ascenso P. -

Birth and Evolution of Korean Reality Show Formats

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Film, Media & Theatre Dissertations School of Film, Media & Theatre Spring 5-6-2019 Dynamics of a Periphery TV Industry: Birth and Evolution of Korean Reality Show Formats Soo keung Jung [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/fmt_dissertations Recommended Citation Jung, Soo keung, "Dynamics of a Periphery TV Industry: Birth and Evolution of Korean Reality Show Formats." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2019. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/fmt_dissertations/7 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Film, Media & Theatre at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Film, Media & Theatre Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DYNAMICS OF A PERIPHERY TV INDUSTRY: BIRTH AND EVOLUTION OF KOREAN REALITY SHOW FORMATS by SOOKEUNG JUNG Under the Direction of Ethan Tussey and Sharon Shahaf, PhD ABSTRACT Television format, a tradable program package, has allowed Korean television the new opportunity to be recognized globally. The booming transnational production of Korean reality formats have transformed the production culture, aesthetics and structure of the local television. This study, using a historical and practical approach to the evolution of the Korean reality formats, examines the dynamic relations between producer, industry and text in the -

God in Chinatown

RELIGION, RACE, AND ETHNICITY God in Chinatown General Editor: Peter J. Paris Religion and Survival in New York's Public Religion and Urban Transformation: Faith in the City Evolving Immigrant Community Edited by Lowell W. Livezey Down by the Riverside: Readings in African American Religion Edited by Larry G. Murphy New York Glory: Kenneth ]. Guest Religions in the City Edited by Tony Carnes and Anna Karpathakis Religion and the Creation of Race and Ethnicity: An Introduction Edited by Craig R. Prentiss God in Chinatown: Religion and Survival in New York's Evolving Immigrant Community Kenneth J. Guest 111 New York University Press NEW YORK AND LONDON NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS For Thomas Luke New York and London www.nyupress.org © 2003 by New York University All rights reserved All photographs in the book, including the cover photos, have been taken by the author. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Guest, Kenneth J. God in Chinatown : religion and survival in New York's evolving immigrant community I Kenneth J. Guest. p. em.- (Religion, race, and ethnicity) Includes bibliographical references (p. 209) and index. ISBN 0-8147-3153-8 (cloth) - ISBN 0-8147-3154-6 (paper) 1. Immigrants-Religious life-New York (State)-New York. 2. Chinese Americans-New York (State )-New York-Religious life. 3. Chinatown (New York, N.Y.) I. Title. II. Series. BL2527.N7G84 2003 200'.89'95107471-dc21 2003000761 New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. Manufactured in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Chinatown and the Fuzhounese 37 36 Chinatown and the Fuzhounese have been quite successful, it also includes many individuals who are ex tremely desperate financially and emotionally. -

The Welsh Seal of the National Assembly for Wales

The Welsh Seal of the National Assembly for Wales The Great Seal of the Realm is the chief seal of the Crown, used to show the Monarch's approval of important state documents. The practice of using this seal began in the reign of Edward the Confessor in the eleventh century, when a double-sided metal matrix with an image of the Sovereign was used to make an impression in wax for attachment by ribbon or cord to Royal documents. The seal meant that the monarch did not need to sign every official document in person; authorisation could be carried out instead by an appointed officer. Between 2007 and 2011 proposed Measures passed by the National Assembly for Wales were subject to “Royal Approval”. Separate Great Seals exist for Scotland and Northern Ireland and, from 2011, a Seal for Wales now exists. Royal Assent Royal Assent is the Monarch's agreement to make a Bill into an Act of the National Assembly for Wales. Royal Assent is conferred by the Monarch signing Letters Patent under the Welsh Seal. The Monarch's agreement to give her assent to a Bill is automatic. Student Research Look for examples of Seals using your school library, local library and the internet. Also research Signet Rings which were worn as jewellery and used by individuals to seal their initials or coat of arms into wax seals on important documents and letters. Form of Letters Patent “ELIZABETH THE SECOND by the Grace of God of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and of Our other Realms and Territories Queen Head of the Commonwealth Defender of the -

Memorial Inscriptions Bathwick LHS D-426

St Mary the Virgin, Bathwick – Smallcombe Cemetery – Memorial Inscriptions Bathwick LHS Row P Names Inscriptions Notes D.P.25 Dorothy Harrison East: Bullock (1836-1914) In Loving Memory Edward Bullock of (1799-) DOROTHY HARRISON BULLOCK 2ND DAUGHTER OF Georgiana Sarah EDWARD BULLOCK ESQRE Bullock (1837-1922) SOME YEARS COMMON SERJEANT OF THE CITY OF LONDON FELL ASLEEP JANUARY 11TH 1914 Cross on 3 plinths. ―•― “HE GIVETH HIS BELOVED SLEEP.” In the 1851 census at 40 Woburn Square, Bloomsbury, London: Edward South: Bullock, aged 51 widower, Common Sergt of London, born at Spanish Also of Town, Jamaica, children: Catherine Elizth, aged 18, born at GEORGIANA Bloomsbury, Dorothy H, aged 14, born at Bloomsbury, and Georgiana, SARAH BULLOCK aged 13, born at Bloomsbury, a governess and three servants. YOUNGER DAUGHTER OF EDWARD BULLOCK ESQRE From The Edinburgh Gazette of Tue 27 Dec 1853 (No. 6346 p1033) FELL ASLEEP APRIL 16TH 1922. WHITEHALL, December 1, 1853. ― The Queen has been pleased to issue a new Commission of “O LORD IN THEE I HAVE TRUSTED.” Lieutenancy for the City of London, constituting and appointing the several persons under-mentioned to be Her Majesty’s Commissioners for that purpose, viz ... Edward Bullock, Esquire, Common Serjeant of Our City of London, and the Common Serjeant of Our said city for the time being; ... In Cambridge University Calendar for the Year 1857 in an advertisement for the English and Irish Church and University Assurance Society, 4, Trafalgar Square, Charing Cross, London on p 40 one of the trustees is: Edward Bullock, Esq., M.A., (Christ Church, Oxford), late Common Serjeant of London. -

Traceability Study in Shark Products

Traceability study in shark products Dr Heiner Lehr (Photo: © Francisco Blaha, 2015) Report commissioned by the CITES Secretariat This publication was funded by the European Union, through the CITES capacity-building project on aquatic species Contents 1 Summary.................................................................................................................................. 7 1.1 Structure of the remaining document ............................................................................. 9 1.2 Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................... 10 2 The market chain ................................................................................................................... 11 2.1 Shark Products ............................................................................................................... 11 2.1.1 Shark fins ............................................................................................................... 12 2.1.2 Shark meat ............................................................................................................. 12 2.1.3 Shark liver oil ......................................................................................................... 13 2.1.4 Shark cartilage ....................................................................................................... 13 2.1.5 Shark skin .............................................................................................................. -

Colonialism Postcolonialism

SECOND EDITION Colonialism/Postcolonialism is both a crystal-clear and authoritative introduction to the field and a cogently-argued defence of the field’s radical potential. It’s exactly the sort of book teachers want their stu- dents to read. Peter Hulme, Department of Literature, Film and Theatre Studies, University of Essex Loomba is a keen and canny critic of ever-shifting geopolitical reali- ties, and Colonialism/Postcolonialism remains a primer for the aca- demic and common reader alike. Antoinette Burton, Department of History, University of Illinois It is rare to come across a book that can engage both student and specialist. Loomba simultaneously maps a field and contributes provocatively to key debates within it. Situated comparatively across disciplines and cultural contexts, this book is essential reading for anyone with an interest in postcolonial studies. Priyamvada Gopal, Faculty of English, Cambridge University Colonialism/Postcolonialism moves adroitly between the general and the particular, the conceptual and the contextual, the local and the global, and between texts and material processes. Distrustful of established and self-perpetuating assumptions, foci and canonical texts which threaten to fossilize postcolonial studies as a discipline, Loomba’s magisterial study raises many crucial issues pertaining to social structure and identity; engaging with different modes of theory and social explanation in the process. There is no doubt that this book remains the best general introduction to the field. Kelwyn Sole, English Department, University of Cape Town Lucid and incisive this is a wonderful introduction to the contentious yet vibrant field of post-colonial studies. With consummate ease Loomba maps the field, unravels the many strands of the debate and provides a considered critique. -

Transnational Ireland on Stage: America to Middle East in Three Texts

Transnational Ireland on Stage: America to Middle East in Three Texts Wei H. Kao Introduction: Between the Local and the Global on the Irish Stage Historically, the comprehensive Anglicisation of Ireland from the early nineteenth century, and the geopolitical location of Ireland in Europe, have laid the foundations for more Irish participation on the world stage. The rapid globalisation process, however, has not fully removed the frustration buried deep in the Irish psyche about the country still being in partition, but it has encouraged many contemporary playwrights to express concerns regarding other areas that are just as troubled as the state of their country, despite the fact that the Northern Ireland issue is not yet fully resolved. It is noteworthy that globalisation, as the continuation of nineteenth- and twentieth-century imperialism in a new form, not only carries forward the exercise of colonial incursion but facilitates the oppressively homogenising effects on the less advantaged Other. This is partly due to the rise of critical theory to ‘productively complicate the nationalist paradigm’ by embarking on transnationalism since the 1970s.1 One consequence of this was to prompt reevaluations of existing cultural productions, thus initiating cross-cultural and interethnic dialogues that had usually been absent in colonial and Eurocentric establishments, and prompting the public to envisage the Other across both real and imagined borders. Even more significantly, the meaning of a text starts to shift if it is studied in an international context, and this applies particularly to a text in which the characters venture into unexplored territories and impel ‘meaning [to] transform as it travels’.2 The transformation of meanings is further accelerated by intercultural encounters that are motivated by globalisation that interconnects individuals and societies around the world. -

The Role of Indigenous Languages in Southern Sudan: Educational Language Policy and Planning

The Role of Indigenous Languages in Southern Sudan: Educational Language Policy and Planning H. Wani Rondyang A thesis submitted to the Institute of Education, University of London, for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2007 Abstract This thesis aims to questions the language policy of Sudan's central government since independence in 1956. An investigation of the root causes of educational problems, which are seemingly linked to the current language policy, is examined throughout the thesis from Chapter 1 through 9. In specific terms, Chapter 1 foregrounds the discussion of the methods and methodology for this research purposely because the study is based, among other things, on the analysis of historical documents pertaining to events and processes of sociolinguistic significance for this study. The factors and sociolinguistic conditions behind the central government's Arabicisation policy which discourages multilingual development, relate the historical analysis in Chapter 3 to the actual language situation in the country described in Chapter 4. However, both chapters are viewed in the context of theoretical understanding of language situation within multilingualism in Chapter 2. The thesis argues that an accommodating language policy would accord a role for the indigenous Sudanese languages. By extension, it would encourage the development and promotion of those languages and cultures in an essentially linguistically and culturally diverse and multilingual country. Recommendations for such an alternative educational language policy are based on the historical and sociolinguistic findings in chapters 3 and 4 as well as in the subsequent discussions on language policy and planning proper in Chapters 5, where theoretical frameworks for examining such issues are explained, and Chapters 6 through 8, where Sudan's post-independence language policy is discussed. -

Cavendish the Experimental Life

Cavendish The Experimental Life Revised Second Edition Max Planck Research Library for the History and Development of Knowledge Series Editors Ian T. Baldwin, Gerd Graßhoff, Jürgen Renn, Dagmar Schäfer, Robert Schlögl, Bernard F. Schutz Edition Open Access Development Team Lindy Divarci, Georg Pflanz, Klaus Thoden, Dirk Wintergrün. The Edition Open Access (EOA) platform was founded to bring together publi- cation initiatives seeking to disseminate the results of scholarly work in a format that combines traditional publications with the digital medium. It currently hosts the open-access publications of the “Max Planck Research Library for the History and Development of Knowledge” (MPRL) and “Edition Open Sources” (EOS). EOA is open to host other open access initiatives similar in conception and spirit, in accordance with the Berlin Declaration on Open Access to Knowledge in the sciences and humanities, which was launched by the Max Planck Society in 2003. By combining the advantages of traditional publications and the digital medium, the platform offers a new way of publishing research and of studying historical topics or current issues in relation to primary materials that are otherwise not easily available. The volumes are available both as printed books and as online open access publications. They are directed at scholars and students of various disciplines, and at a broader public interested in how science shapes our world. Cavendish The Experimental Life Revised Second Edition Christa Jungnickel and Russell McCormmach Studies 7 Studies 7 Communicated by Jed Z. Buchwald Editorial Team: Lindy Divarci, Georg Pflanz, Bendix Düker, Caroline Frank, Beatrice Hermann, Beatrice Hilke Image Processing: Digitization Group of the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science Cover Image: Chemical Laboratory. -

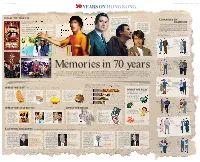

Mainland Hong Kong

6 | Monday, October 21, 2019 HONG KONG EDITION | CHINA DAILY 7 In 1980, the Hong Kong TV series Wong Kar-wai’s fi lm, Days of Being Wild, played by Chow in 1990, brought Leslie Cheung his first Yun-fat, The Bund, Best Actor trophy in the Hong Kong Film Popular mainland TV dramas in HK swept up both Hong Awards. Along with many other classical and TVB rating rankings Kong and Chinese diverse screen images In the 1990s, Hong Kong mainland television he created, Cheung actor and director Stephen Fashion changes over time. But closer interaction and mutual infl u- Ye a r Drama Ranking In the ’70s, Hong Kong audiences with its remains one Chow gained fame through ence can be seen through ever-changing fashion styles of Hong Kong 2000 Records of Kangxi’s Travel Incognito 10 kung fu star Bruce Lee checkered plots and of the most his unconventional “silly and the mainland over the past 70 years. The two parallel fashion took Chinese martial arts powerful theme song. iconic actors talk” humor, earning him styles began to overlap in the 1970s when Hong Kong movies and TV 2006 The Return of the Condor Heroes 3 to Hollywood for the fi rst in the city’s the nickname dramas dominated the Chinese-speaking world. The interaction of the time. His movies gained movie “the king of two places grew much more intense under the impact of globalization 2015 The Empress of China 2 enormous success around history. comedy”. in the 21st century. 2018 Story of Yanxi Palace 1 the world.