Che Guevara and Revolutionary Christianity in Latin America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Slum Clearance in Havana in an Age of Revolution, 1930-65

SLEEPING ON THE ASHES: SLUM CLEARANCE IN HAVANA IN AN AGE OF REVOLUTION, 1930-65 by Jesse Lewis Horst Bachelor of Arts, St. Olaf College, 2006 Master of Arts, University of Pittsburgh, 2012 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2016 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS & SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Jesse Horst It was defended on July 28, 2016 and approved by Scott Morgenstern, Associate Professor, Department of Political Science Edward Muller, Professor, Department of History Lara Putnam, Professor and Chair, Department of History Co-Chair: George Reid Andrews, Distinguished Professor, Department of History Co-Chair: Alejandro de la Fuente, Robert Woods Bliss Professor of Latin American History and Economics, Department of History, Harvard University ii Copyright © by Jesse Horst 2016 iii SLEEPING ON THE ASHES: SLUM CLEARANCE IN HAVANA IN AN AGE OF REVOLUTION, 1930-65 Jesse Horst, M.A., PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2016 This dissertation examines the relationship between poor, informally housed communities and the state in Havana, Cuba, from 1930 to 1965, before and after the first socialist revolution in the Western Hemisphere. It challenges the notion of a “great divide” between Republic and Revolution by tracing contentious interactions between technocrats, politicians, and financial elites on one hand, and mobilized, mostly-Afro-descended tenants and shantytown residents on the other hand. The dynamics of housing inequality in Havana not only reflected existing socio- racial hierarchies but also produced and reconfigured them in ways that have not been systematically researched. -

Ortega for President: the Religious Rebirth of Sandinismo in Nicaragua

European Review of Latin American and Caribbean Studies 89, October 2010 | 47-63 Ortega for President: The Religious Rebirth of Sandinismo in Nicaragua Henri Gooren Abstract: This article analyses various connections between Daniel Ortega’s surprising victory in the presidential elections of 5 November 2006, his control of the Frente Sandinista de la Liberación Nacio- nal (FSLN) party, and the changing religious context in Nicaragua, where Pentecostal churches now claim almost one quarter of the population. To achieve this, I draw from my fieldwork in Nicaragua in 2005 and 2006, which analysed competition for members between various religious groups in Managua: charismatic Catholics, the Assemblies of God, the neo-Pentecostal mega-church Hosanna, and the Mormon Church. How did Ortega manage to win the votes from so many religious people (evangelical Protestants and Roman Catholics alike)? And how does this case compare to similar cases of populist leaders in Latin America courting evangelicals, like Chávez in Venezuela and earlier Fujimori in Peru? Keywords: Nicaragua, religion, elections, FSLN, Daniel Ortega. Populist leadership and evangelical support in Latin America At first look, the case of Ortega’s surprise election victory seems to fit an estab- lished pattern in Latin America: the populist leader who comes to power in part by courting – and winning – the evangelical vote. Alberto Fujimori in Peru was the first to achieve this in the early 1990s, followed by Venezuelan lieutenant-colonel Hugo Chávez in the late 1990s and more recently Rafael Correa in Ecuador (Op- penheimer 2006). These three populist leaders came to power thanks to the break- down of an old party system, which gradually became stagnant and corrupted. -

Nicaragua Page 1 of 4

Nicaragua Page 1 of 4 Nicaragua International Religious Freedom Report 2008 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor The Constitution provides for freedom of religion, and other laws and policies contributed to the generally free practice of religion. The law at all levels protects this right in full against abuse, either by governmental or private actors. The Government generally respected religious freedom in practice. There was no change in the status of respect for religious freedom by the Government during the period covered by this report. There were no reports of societal abuses or discrimination based on religious affiliation, belief, or practice. The U.S. Government discusses religious freedom with the Government as part of its overall policy to promote human rights. Section I. Religious Demography The country has an area of 49,998 square miles and a population of 5.7 million. More than 80 percent of the population belongs to Christian groups. Roman Catholicism remains the dominant religion. According to a 2005 census conducted by the governmental Nicaraguan Institute of Statistics and Census (INEC), 58.5 percent of the population is Roman Catholic and 21.6 percent is evangelical Protestant including Assembly of God, Pentecostal, Mennonite, and Baptist. Groups that constitute less than 5 percent include the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormons), the Moravian Church, and Jehovah's Witnesses. Both Catholic and evangelical leaders view the census results as inaccurate; according to their own surveys Catholics constitute approximately 75 percent of the population and evangelicals 30 percent. The most recent 2008 public opinion survey from the private polling firm M&R indicates that 58 percent are Catholic and 28 percent evangelical. -

Cuba Travelogue 2012

Havana, Cuba Dr. John Linantud Malecón Mirror University of Houston Downtown Republic of Cuba Political Travelogue 17-27 June 2012 The Social Science Lectures Dr. Claude Rubinson Updated 12 September 2012 UHD Faculty Development Grant Translations by Dr. Jose Alvarez, UHD Ports of Havana Port of Mariel and Matanzas Population 313 million Ethnic Cuban 1.6 million (US Statistical Abstract 2012) Miami - Havana 1 Hour Population 11 million Negative 5% annual immigration rate 1960- 2005 (Human Development Report 2009) What Normal Cuba-US Relations Would Look Like Varadero, Cuba Fisherman Being Cuban is like always being up to your neck in water -Reverend Raul Suarez, Martin Luther King Center and Member of Parliament, Marianao, Havana, Cuba 18 June 2012 Soplillar, Cuba (north of Hotel Playa Giron) Community Hall Questions So Far? José Martí (1853-95) Havana-Plaza De La Revolución + Assorted Locations Che Guevara (1928-67) Havana-Plaza De La Revolución + Assorted Locations Derek Chandler International Airport Exit Doctor Camilo Cienfuegos (1932-59) Havana-Plaza De La Revolución + Assorted Locations Havana Museo de la Revolución Batista Reagan Bush I Bush II JFK? Havana Museo de la Revolución + Assorted Locations The Cuban Five Havana Avenue 31 North-Eastbound M26=Moncada Barracks Attack 26 July 1953/CDR=Committees for Defense of the Revolution Armed Forces per 1,000 People Source: World Bank (http://databank.worldbank.org/data/Home.aspx) 24 May 12 Questions So Far? pt. 2 Marianao, Havana, Grade School Fidel Raul Che Fidel Che Che 2+4=6 Jerry Marianao, Havana Neighborhood Health Clinic Fidel Raul Fidel Waiting Room Administrative Area Chandler Over Entrance Front Entrance Marianao, Havana, Ration Store Food Ration Book Life Expectancy Source: World Bank (http://databank.worldbank.org/data/Home.aspx) 24 May 12. -

Ernesto 'Che' Guevara: the Existing Literature

Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara: socialist political economy and economic management in Cuba, 1959-1965 Helen Yaffe London School of Economics and Political Science Doctor of Philosophy 1 UMI Number: U615258 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615258 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 I, Helen Yaffe, assert that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Helen Yaffe Date: 2 Iritish Library of Political nrjPr v . # ^pc £ i ! Abstract The problem facing the Cuban Revolution after 1959 was how to increase productive capacity and labour productivity, in conditions of underdevelopment and in transition to socialism, without relying on capitalist mechanisms that would undermine the formation of new consciousness and social relations integral to communism. Locating Guevara’s economic analysis at the heart of the research, the thesis examines policies and development strategies formulated to meet this challenge, thereby refuting the mainstream view that his emphasis on consciousness was idealist. Rather, it was intrinsic and instrumental to the economic philosophy and strategy for social change advocated. -

The Embattled Political Aesthetics of José Carlos Mariátegui and Amauta

A Realist Indigenism: The Embattled Political Aesthetics of José Carlos Mariátegui and Amauta BY ERIN MARIA MADARIETA B.A., University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2012 THESIS Submitted as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Chicago, 2019 Chicago, Illinois Defense Committee: Blake Stimson, Art History, Advisor and Chair Andrew Finegold, Art History Nicholas Brown, English Margarita Saona, Hispanic and Italian Studies TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………………………...1 BEYOND THE “SECTARIAN DIVIDE”: MARIÁTEGUI’S EXPANSIVE REALISM………..9 TOWARD A REALIST INDIGENISM: PARSING MARXISM, INDIGENISM, AND POPULISM………………………………………………………………………………………33 “THE PROBLEM OF RACE IN LATIN AMERICA”: MARIÁTEGUI AND INTERNATIONAL COMMUNISTS…………………………………………………………...53 “PAINTING THE PEOPLE” OR DEMYSTIFYING PERUVIAN REALITY?: AMAUTA’S VISUAL CONTENT…………………………………………………………………………….65 CONCLUSION…………………………….…………………………………………………….88 BIBLIOGRAPHY………………………………………………………………………………..92 ii SUMMARY This thesis focuses on José Carlos Mariátegui (1894-1930), a Peruvian critic and Marxist political activist who founded the Peruvian Socialist Party. Mariátegui also edited the journal Amauta, which featured literature, visual art, and theoretical and political texts from 1926 to 1930. This project aims to contribute an original understanding of the thought and editorial practice of this historically significant figure by recuperating his endorsement of realist -

Box1 Folder 45 2.Pdf

e~'~/ .#'~; /%4 ~~ ~/-cu- 0 ~/tJD /~/~/~ :l,tJ-O ~~ bO:cJV " " . INTERNA TIONA L Although more Japanese women a.re working out.ide the home than ever belore, a recent lurvey trom that country lndicateB that they a re not likely to get very high on the eorpotate la.dder. The survey, carried out by a women-, magazlne, polled 500 Japanese corpora.tions on the qualltles they look tor when seekl.l'1! a temale staff member. I Accordlng to lhe KyGdo News Service.! 95'0 of the eompanlel said they look fop female workers who are cheerful and obedLent; 9Z% sou.,ht cooperative women; and 85% wanted temale employees wllllng to take respoDs!bllity. Moat firms indtcated that they seek women worker, willLng to perform tasks such as copying and making tea. CFS National Office 3540 14th Street Detroit, Michigan 48208 (31 3) 833-3987 Christians For Socialism in the u.S. Formerl y known as American Christians Toward Socialism (A CTS), CFS in the US " part of the international movement of Christians for Socialism. INTERN..A TIONA L December 10 i. Human Rightl Day aroUnd the world. But Ln Talwan, the arrests in recent yeaI'I of feminists, IdDIibt clvll rlghts advocate., lntellec.uals, and re11gious leaders only symbolize the lack of human rlghts. I Two years ago on Dec. 10 In Taiwan, a human rights day rally exploded 1nto violence ~nd more than ZOO people were arrested. E1ght of them, including two lemlnl.t leaders. were tried by milltary tribunal for "secUtlon, it convicted and received sentences of from 1Z years to Ufe. -

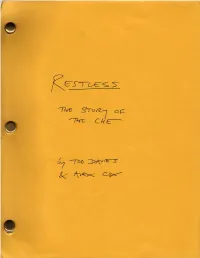

Restless.Pdf

RESTLESS THE STORY OF EL ‘CHE’ GUEVARA by ALEX COX & TOD DAVIES first draft 19 jan 1993 © Davies & Cox 1993 2 VALLEGRANDE PROVINCE, BOLIVIA EXT EARLY MORNING 30 JULY 1967 In a deep canyon beside a fast-flowing river, about TWENTY MEN are camped. Bearded, skinny, strained. Most are asleep in attitudes of exhaustion. One, awake, stares in despair at the state of his boots. Pack animals are tethered nearby. MORO, Cuban, thickly bearded, clad in the ubiquitous fatigues, prepares coffee over a smoking fire. "CHE" GUEVARA, Revolutionary Commandant and leader of this expedition, hunches wheezing over his journal - a cherry- coloured, plastic-covered agenda. Unable to sleep, CHE waits for the coffee to relieve his ASTHMA. CHE is bearded, 39 years old. A LIGHT flickers on the far side of the ravine. MORO Shit. A light -- ANGLE ON RAUL A Bolivian, picking up his M-1 rifle. RAUL Who goes there? VOICE Trinidad Detachment -- GUNFIRE BREAKS OUT. RAUL is firing across the river at the light. Incoming bullets whine through the camp. EVERYONE is awake and in a panic. ANGLE ON POMBO CHE's deputy, a tall Black Cuban, helping the weakened CHE aboard a horse. CHE's asthma worsens as the bullets fly. CHE Chino! The supplies! 3 ANGLE ON CHINO Chinese-Peruvian, round-faced and bespectacled, rounding up the frightened mounts. OTHER MEN load the horses with supplies - lashing them insecurely in their haste. It's getting light. SOLDIERS of the Bolivian Army can be seen across the ravine, firing through the trees. POMBO leads CHE's horse away from the gunfire. -

Che Guevara's Final Verdict on the Soviet Economy

SOCIALIST VOICE / JUNE 2008 / 1 Contents 249. Che Guevara’s Final Verdict on the Soviet Economy. John Riddell 250. From Marx to Morales: Indigenous Socialism and the Latin Americanization of Marxism. John Riddell 251. Bolivian President Condemns Europe’s Anti-Migrant Law. Evo Morales 252. Harvest of Injustice: The Oppression of Migrant Workers on Canadian Farms. Adriana Paz 253. Revolutionary Organization Today: Part One. Paul Le Blanc and John Riddell 254. Revolutionary Organization Today: Part Two. Paul Le Blanc and John Riddell 255. The Harper ‘Apology’ — Saying ‘Sorry’ with a Forked Tongue. Mike Krebs ——————————————————————————————————— Socialist Voice #249, June 8, 2008 Che Guevara’s Final Verdict on the Soviet Economy By John Riddell One of the most important developments in Cuban Marxism in recent years has been increased attention to the writings of Ernesto Che Guevara on the economics and politics of the transition to socialism. A milestone in this process was the publication in 2006 by Ocean Press and Cuba’s Centro de Estudios Che Guevara of Apuntes criticos a la economía política [Critical Notes on Political Economy], a collection of Che’s writings from the years 1962 to 1965, many of them previously unpublished. The book includes a lengthy excerpt from a letter to Fidel Castro, entitled “Some Thoughts on the Transition to Socialism.” In it, in extremely condensed comments, Che presented his views on economic development in the Soviet Union.[1] In 1965, the Soviet economy stood at the end of a period of rapid growth that had brought improvements to the still very low living standards of working people. -

La Sociedad Civil En La Revolución Cubana (1959-2012)

Port_Revolucion_01_trz.FH9 Tue Mar 22 11:56:01 2016 Página 1 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Composición SSociedadociedad CivilCivil Cubana.inddCubana.indd 2 11/3/16/3/16 009:20:489:20:48 La sociedad civil en la Revolución cubana (1959-2012) SSociedadociedad CivilCivil Cubana.inddCubana.indd 3 222/3/162/3/16 111:22:051:22:05 SSociedadociedad CivilCivil Cubana.inddCubana.indd 4 11/3/16/3/16 009:20:489:20:48 La sociedad civil en la Revolución cubana (1959-2012) Joseba Macías SSociedadociedad CivilCivil Cubana.inddCubana.indd 5 222/3/162/3/16 111:22:051:22:05 CIP. Biblioteca Universitaria Macías Amores, Joseba La sociedad civil en la Revolución cubana (1959-2012) / Joseba Macías. – Bilbao : Universidad del País Vasco / Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea, Argitalpen Zerbitzua = Servicio Editorial, D.L. 2016. – 608 p.; 24 cm. Bibliog.: p. [571]-608. D.L.: BI-406-2016. — ISBN: 978-84-9082-385-9 1. Cuba – Historia – 1959 (Revolución). 2. Cuba – Historia – 1959- 972.91 “1959/...” Foto de portada/Azalaren argazkia: © Servicio Editorial de la Universidad del País Vasco Euskal Herriko Unibertsitateko Argitalpen Zerbitzua ISBN: 978-84-9082-385-9 Depósito legal/Lege gordailua: BI-406-2016 SSociedadociedad CivilCivil Cubana.inddCubana.indd 6 118/3/168/3/16 009:49:189:49:18 A Miren que, esté donde esté, sigue galopando a nuestro lado. Suerte siempre. SSociedadociedad CivilCivil Cubana.inddCubana.indd 7 117/3/167/3/16 117:59:027:59:02 SSociedadociedad CivilCivil Cubana.inddCubana.indd 8 117/3/167/3/16 117:59:027:59:02 ÍNDICE Prólogo (Jorge Luis Acanda). -

In the Liberation Struggle

11 Latin Rmerican Christians inthe Liberation Struggle Since the Latin American Catholic Bishops the People's United Front. When this failed, due met in Medellin, Colombia in August and September to fragmentation and mistrust on the left and the 1968 to call for basic changes in the region, the repression exercised by the government, he joined Catholic Church has been increasingly polarized the National Liberation Army in the mountains. between those who heard their words from the He soon fell in a skirmish with government troops point of view of the suffering majorities and advised by U.S. counterinsurgency experts. those who heard them from the point of view of Camilo's option for violence has clearly affected the vested interests. The former found in the the attitudes of Latin American Christians, but Medellin documents, as in certain documents of so also has his attempt to build a United Front, the Second Vatican Council and the social ency- as we shall see in the Dominican piece which fol- clicals of Popes Paul VI and John XXIII, the lows. But more importantly, Camilo lent the fire legitimation of their struggles for justice and of committed love to the Christian forces for their condemnations of exploitation and struc- change around the continent. To Camilo it had tures of domination. The Latin American Bishops become apparent that the central meaning of his had hoped that their call published in Medellin Catholic commitment would only be found in the would be enough, all too hastily retreating from love of his neighbor. And he saw still more their public declarations when their implications clearly that love which does not find effective became apparent. -

Huber Matos Incansable Defensor De La Libertad En Cuba

Personajes Públicos Nº 003 Marzo de 2014 Huber Matos Incansable defensor de la libertad en Cuba. Este 27 de febrero murió en Miami, de un ataque al corazón, a los 95 años. , Huber Matos nació en 1928 en Yara, Cuba. guerra le valió entrar con Castro y Cienfue- El golpe de Estado de Fulgencio Batista (10 gos en La Habana, en la marcha de los vence- de marzo de 1952) lo sorprendió a sus veinti- dores (como se muestra en la imagen). cinco años, ejerciendo el papel de profesor en una escuela de Manzanillo. Años antes había conseguido un doctorado en Pedagogía por la Universidad de La Habana, lo cual no impidió, sin embargo, que se acoplara como paramili- tar a la lucha revolucionaria de Fidel Castro. Simpatizante activo del Partido Ortodoxo (de ideas nacionalistas y marxistas), se unió al Movimiento 26 de Julio (nacionalista y antiimperialista) para hacer frente a la dicta- dura de Fulgencio Batista, tras enterarse de la muerte de algunos de sus pupilos en la batalla De izquierda a derecha y en primer plano: de Alegría de Pío. El movimiento le pareció Camilo Cienfuegos, Fidel Castro y Huber Matos. atractivo, además, porque prometía volver a la legalidad y la democracia, y respetar la Una vez conquistado el país, recibió la Constitución de 1940. Arrestado por su comandancia del Ejército en Camagüey, pero oposición a Batista, escapó exitosamente a adoptó una posición discrepante de Fidel, a Costa Rica, país que perduró sentimental- quien atribuyó un planteamiento comunista, mente en su memoria por la acogida que le compartido por el Ché Guevara y Raúl dio como exiliado político.