Mapping STATELESSNESS in Austria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Country Code Country Name National Client Identifier Format

Country Country National client Format of the identifier Potential source of the information code name identifier AT Austria CONCAT Belgian National Number 11 numerical digits where the first 6 are the date of birth (YYMMDD), the next 3 are an BE Belgium (Numéro de registre National ID ordering number (uneven for men, even for women) and the last 2 a check digit. national - Rijksregisternummer) CONCAT It consists of 10 digits. The first 6 are the date of birth (YYMMDD). The next 3 digits Bulgarian Personal have information about the area in Bulgaria and the order of birth, and the ninth digit is BG Bulgaria Passport, National ID, Driving Licence Number even for a boy and odd for a girl. Seventh and eighth are randomly generated according to the city. The tenth digit is a check digit. CONCAT The number for passports issued before 13/12/2010 consists of the character 'E' The passport is issued by the Civil National Passport CY Cyprus followed by 6 digits i.e E123456. Biometric passports issued after 13/12/2010 have a Registry Department of the Ministry Number number that starts with the character 'K', followed by 8 digits. i.e K12345678 of Interior. CONCAT It is a nine or ten-digit number in the format of YYXXDD/SSSC, where XX=MM (month of birth) for male, i.e. numbers 01-12, and XX=MM+50 (or exceptionally XX=MM+70) for female, i.e. numbers 51-62 (or 71-82). For example, a number 785723 representing the It is assigned to a person shortly after first six digits is assigned to a woman born on 23rd of July 1978. -

Report for Austria– Questionnaire Related the Administration Control

ADMINISTRATIVE JUSTICE IN EUROPE – Report for Austria– Questionnaire related the administration control list and typology in the 25 Member States of the European Union Preliminary. 1. Administration jurisdictional control was one typical concern of the liberal streams in the 19th century. In Austria, “the Reichsgericht”, a precursor of the Constitutional Court, was created by the December 1867 constitution which also planned creation of a Supreme Administrative Court (hereafter “the Verwaltungsgerichtshof”). However, this project was only fulfilled in 1876. Following this, the Verwaltungsgerichtshof played a decisive role in developing the legal protection system in Austria, establishing fundamental principles for administrative procedural law. Between 1934 and 1938, the Constitutional Court and the Verwaltungsgerichtshof merged to become “the Bundesgerichtshof”. Several judges were retired for political reasons. The introductions of Chambers with extended composition and of actions for administrative failure to act were significant reforms. After 1938, “the Bundesgerichtshof” lost its authority as Constitutional Court as well as several of its administrative jurisdiction authorities. Several judges were retired for political reasons. In 1940 “the Bundesgerichtshof” became “the Verwaltungsgerichtshof in Vienna” which was an administrative authority of the Reich. In 1941, the Verwaltungsgerichtshof became the “Vienna Außensenat” of the “Reichsverwaltungsgericht” by forming an organisational association with other German administrative courts. A few weeks after the Austrian declaration of independence in 1945, Chancellor Renner commissioned Mr. Coreth to revive the Verwaltungsgerichtshof which took up its duties again on 7th December 1945. The legal text on the Verwaltungsgerichtshof was amended and reissued several times but, in substance, it is still in force today. In 1945, the Constitutional Court was re-established with the same capacities as 1933 and it began carrying out its duties again in 1946. -

Sources for Genealogical Research at the Austrian War Archives in Vienna (Kriegsarchiv Wien)

SOURCES FOR GENEALOGICAL RESEARCH AT THE AUSTRIAN WAR ARCHIVES IN VIENNA (KRIEGSARCHIV WIEN) by Christoph Tepperberg Director of the Kriegsarchiv 1 Table of contents 1. The Vienna War Archives and its relevance for genealogical research 1.1. A short history of the War Archives 1.2. Conditions for doing genealogical research at the Kriegsarchiv 2. Sources for genealogical research at the Kriegsarchiv 2. 1. Documents of the military administration and commands 2. 2. Personnel records, and records pertaining to personnel 2.2.1. Sources for research on military personnel of all ranks 2.2.2. Sources for research on commissioned officers and military officials 3. Using the Archives 3.1. Regulations for using personnel records 3.2. Visiting the Archives 3.3. Written inquiries 3.4. Professional researchers 4. Relevant publications 5. Sources for genealogical research in other archives and institutions 5.1. Sources for genealogical research in other departments of the Austrian State Archives 5.2. Sources for genealogical research in other Austrian archives 5.3. Sources for genealogical research in archives outside of Austria 5.3.1. The provinces of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy and its “successor states” 5.3.2. Sources for genealogical research in the “successor states” 5.4. Additional points of contact and practical hints for genealogical research 2 1. The Vienna War Archives and its relevance for genealogical research 1.1. A short history of the War Archives Today’s Austrian Republic is a small country, but from 1526 to 1918 Austria was a great power, we can say: the United States of Middle and Southeastern Europe. -

The Empire in the Provinces: the Case of Carinthia

religions Article The Empire in the Provinces: The Case of Carinthia Helmut Konrad Institut für Geschichte, Karl-Franzens-Universität Graz, Attemsgasse 8/II, [505] 8010 Graz, Austria; [email protected] Academic Editors: Malachi Hacohen and Peter Iver Kaufman Received: 16 May 2016; Accepted: 1 August 2016; Published: 5 August 2016 Abstract: This article examines the legacy of the Habsburg Monarchy in the First Austrian Republic, both in the capital, Vienna, and in the province of Carinthia. It concludes that Social Democracy, often cited as one of the six ingredients that held the old Empire together, took on distinct forms in the Republic’s different federal states. The scholarly literature on the post-1918 “heritage” of the Monarchy therefore needs to move beyond monolithic generalizations and toward regionally focused comparative studies. Keywords: empire; socialism; Jews; Habsburg Monarchy; Austria; Vienna; Carinthia; German Nationalism; Sprachenkampf 1. Introduction Which forms did the ideas take that allowed the Habsburg monarchy to persist, despite the diversity of nationalisms present in the small Republic of German-Austria, for so long after the end of the First World War? What was the “glue” that held this multiethnic empire together, when its collapse had been predicted since 1848, and which of its elements continued to exist beyond 1918? How was this heritage expressed in the different regions of the new republic? At least six factors can be identified as ingredients of the “glue” that held the monarchy together: first, the Emperor, a figure who symbolized the fusion of the complex linguistic, ethnic and religious components of the Habsburg state; second, the administrative officials, who were loyal to the Emperor and worked in the ubiquitous and even architecturally similar buildings of the Monarchy’s district authorities and train stations; third, the army, whose members promoted the imperial ideals through their long terms of service and acknowledged linguistic diversity. -

Footpath Description

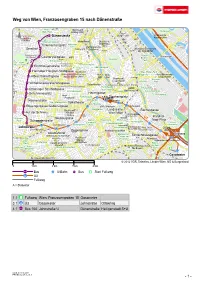

Weg von Wien, Franzosengraben 15 nach Dänenstraße N Hugo- Bezirksamt Wolf- Park Donaupark Döbling (XIX.) Lorenz- Ignaz- Semmelweis- BUS Dänenstraße Böhler- UKH Feuerwache Kaisermühlen Frauenklinik Fin.- BFI Fundamt BUS Türkenschanzpark Verkehrsamt Bezirksamt amt Brigittenau Türkenschanzplatz Währinger Lagerwiese Park Rettungswache (XX.) Gersthof BUS Finanzamt Brigittenau Pensionsversicherung Brigittenau der Angestellten Orthopädisches Rudolf- BUS Donauinsel Kh. Gersthof Czartoryskigasse WIFI Bednar- Währing Augarten Schubertpark Park Dr.- Josef- 10A Resch- Platz Evangelisches AlsergrundLichtensteinpark BUS Richthausenstraße Krankenhaus A.- Carlson- Wettsteinpark Anl. BUS Hernalser Hauptstr./Wattgasse Bezirksamt Max-Winter-Park Allgemeines Krankenhaus Verk.- Verm.- Venediger Au Hauptfeuerwache BUS Albrechtskreithgasse der Stadt Wien (AKH) Amt Amt Leopoldstadt W.- Leopoldstadt Hernals Bezirksamt Kössner- Leopoldstadt Volksprater Park BUS Wilhelminenstraße/Wattgasse (II.) Polizeidirektion Krankenhaus d. Barmherz. Brüder Confraternität-Privatklinik Josefstadt Rudolfsplatz DDSG Zirkuswiese BUS Ottakringer Str./Wattgasse Pass-Platz Ottakring Schönbornpark Rechnungshof Konstantinhügel BUS Schuhmeierplatz Herrengasse Josefstadt Arenawiese BUS Finanzamt Rathauspark U Stephansplatz Hasnerstraße Volksgarten WienU Finanzamt Jos.-Strauss-Park Volkstheater Heldenplatz U A BUS Possingergasse/Gablenzgasse U B.M.f. Finanzen U Arbeitsamt BezirksamtNeubau Burggarten Landstraße- Rochusgasse BUS Auf der Schmelz Mariahilf Wien Mitte / Neubau BezirksamtLandstraßeU -

Der Bezirk Eferding

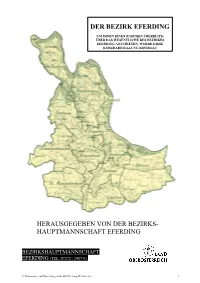

DER BEZIRK EFERDING UM IHNEN EINEN RASCHEN ÜBERBLICK ÜBER DAS WESENTLICHE DES BEZIRKES EFERDING ANZUBIETEN, WURDE DIESE KURZDARSTELLUNG ERSTELLT HERAUSGEGEBEN VON DER BEZIRKS- HAUPTMANNSCHAFT EFERDING BEZIRKSHAUPTMANNSCHAFT EFERDING (TEL. 07272 / 2407-0)) C:\Dokumente und Einstellungen\bhef062\Desktop\Website.doc 1 SACHBEREICHE / AUFGABENGRUPPEN: Amtskasse, Feuerpolizei, Forstwesen, Führerschein- u. Verkehrsangelegenheiten, Kfz-Zulassungsangelegenheiten, Gemeindeangelegenheiten, Gewerbe- u. Energierecht, Informa- tions- u. Beratungsstelle, Jagd- u. Fischereiwesen, Jugendwohlfahrts- u. Familienangelegenhei- ten, Kirchenaustritte, Kultur, Landwirtschaft, Natur- u. Umweltschutz, Bau- u. Wasserrechtsan- gelegenheiten, Pass-, Fremdenpolizei- u. Sicherheitswesen, Personenstands- u. Staatsbürger- schaftswesen, Schulangelegenheiten, Sanitätswesen und Lebensmittelpolizei, Sozialhilfe, Ver- waltungsstrafvollzug, Veranstaltungs- u. Versammlungswesen, Veterinärdienst, Waffenangele- genheiten, Geschäftsstelle des Sozialhilfeverbandes, Bezirksschulrat, Bezirksbildstelle. ALLGEMEINER ÜBERBLICK ÜBER DEN BEZIRK: ● FLÄCHE: 260 km² ● EINWOHNER: 30.711 (endgültiges Ergebnis der Volkszählung 2001) ● 12 GEMEINDEN, flächenmäßig größte Gemeinde ist Alkoven mit 42,6 km², kleinste ist Eferding mit 2,8 km² ● BEZIRKSHAUPTSTADT: Eferding (seit 1222 Stadtrecht, drittälteste Stadt Österreichs) ● GEOLOGISCHER AUFBAU: Das fruchtbare Eferdinger Becken, das sich zwischen Aschach und Wilhering erstreckt, hat eine Länge von 14 km und eine Breite von 9 km. Im Norden wird -

Mittelalter“ »Rad-Kulturreise an Der Donau „Mittelalter“« 2 / 59

Rad-Kulturreise an der Donau „Mittelalter“ »Rad-Kulturreise an der Donau „Mittelalter“« 2 / 59 Rad-Kulturreise an der Donau „Mittelalter“ „Faszination Donau - mittelalterlich erleben“ Die Donau ist mit 2.888 km Länge der zweitgrößte Strom Europas. Auf der Reise von ihrem Ursprung im bayerischen Schwarzwald zu ihrer Mündung im Schwarzen Meer durchquert sie zehn Staaten. Kein Wunder also, dass dieser Fluss seit jeher Kulturen verbindet. Ob als Naturraum, Grenzfluss, Handelsweg, Reiseroute, Heerstraße, … Die einst überragende Bedeutung des Donaustromes ist heute etwas in Vergessenheit geraten, ihr Mythos übt jedoch ungebrochen eine starke Faszination aus. Die Donau - die Lebensader Europas! Auf dieser Rad-Kulturreise entlang der österreichischen Donau begeben wir uns auf die Spur der mittelalterlichen Faszination der Donau. Burgen, Kreuzritter, Machtkämpfe, … das ist der Stoff, aus dem spannende Mittelaltergeschichten sind. Der Donauraum bietet jedoch viel mehr: Die Lebensader des mittelalterlichen Europas lässt förmlich in diese Epoche eintauchen und erlaubt auch abseits der Klischees interessante Einblicke in die Welt des Mittelalters. Viel Spaß beim Entdecken! Ausgangsort: Passau Endort: Hainburg Gesamtlänge: ~ 360 km Dauer: 9 Tage Tipp: In Hinblick auf die Öffnungszeiten der Museen empfiehlt es sich, diese Reise an einem Samstag zu beginnen. Die Reiseplanung ist als Vorschlag zu verstehen, den Sie gerne nach Ihren persönlichen Vorlieben adaptieren können. Sehenswürdigkeiten, die als zusätzliche Insidertipps oder Varianten angeführt sind, -

Comparison of the Shear Bond Strength of 3D Printed Temporary Bridges Materials, on Different Types of Resin Cements and Surface Treatment

J Clin Exp Dent. 2019;11(5):e367-72 Journal section: Operative Dentistry and Endodontics doi:10.4317/jced.55617 Publication Types: Research http://dx.doi.org/10.4317/jced.55617 Comparison of the shear bond strength of 3D printed temporary bridges materials, on different types of resin cements and surface treatment Holmer Lorenz 1, Ahmed Othman 2, Anne-Katrin Lührs 3, Constantin von See 4 1 Dr. med. dent student, Danube Private University, Krems an der Donau, Austria 2 Dr., M.Sc., Digital Orthodontic Researcher, Digital technology in dentistry and CAD/CAM department, Danube Private Univer- sity, Krems an der Donau, Austria 3 DDS, PhD, Senior Lecturer, Department of Conservative Dentistry, Periodontology and Preventive Dentistry, Hannover Medical School, Hannover 3 Prof. Dr., Director of the Center for Digital Technologies in Dentistry and CAD/CAM, Danube Private University, Krems an der Donau, Austria Correspondence: Steiner Landstrasse 124 3500 Krems an der Donau- Austria Lorenz H, Lührs AK, von See C. Comparison of the shear bond strength of [email protected] 3D printed temporary bridges on different types of resin cements and surface treatment. J Clin Exp Dent. 2019;11(5):e367-72. http://www.medicinaoral.com/odo/volumenes/v11i4/jcedv11i4p367.pdf Received: 04/02/2019 Accepted: 18/02/2018 Article Number: 55617 http://www.medicinaoral.com/odo/indice.htm © Medicina Oral S. L. C.I.F. B 96689336 - eISSN: 1989-5488 eMail: [email protected] Indexed in: Pubmed Pubmed Central® (PMC) Scopus DOI® System Abstract Background: Thus, purpose of this study was to compare the shear bond strength of the resin cement and the resin modified glass ionomer cement on 3D printed temporary material for crowns and bridges in combination with di- fferent surface treatment modalities. -

Notes of Michael J. Zeps, SJ

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette History Faculty Research and Publications History Department 1-1-2011 Documents of Baudirektion Wien 1919-1941: Notes of Michael J. Zeps, S.J. Michael J. Zeps S.J. Marquette University, [email protected] Preface While doing research in Vienna for my dissertation on relations between Church and State in Austria between the wars I became intrigued by the outward appearance of the public housing projects put up by Red Vienna at the same time. They seemed to have a martial cast to them not at all restricted to the famous Karl-Marx-Hof so, against advice that I would find nothing, I decided to see what could be found in the archives of the Stadtbauamt to tie the architecture of the program to the civil war of 1934 when the structures became the principal focus of conflict. I found no direct tie anywhere in the documents but uncovered some circumstantial evidence that might be explored in the future. One reason for publishing these notes is to save researchers from the same dead end I ran into. This is not to say no evidence was ever present because there are many missing documents in the sequence which might turn up in the future—there is more than one complaint to be found about staff members taking documents and not returning them—and the socialists who controlled the records had an interest in denying any connection both before and after the civil war. Certain kinds of records are simply not there including assessments of personnel which are in the files of the Magistratsdirektion not accessible to the public and minutes of most meetings within the various Magistrats Abteilungen connected with the program. -

Dismantled Once, Diverged Forever? a Quasi-Natural Experiment of Red Army’ Disassemblies in Post-WWII Europe

Dismantled once, diverged forever? A quasi-natural experiment of Red Army’ disassemblies in post-WWII Europe – EXTENDED ABSTRACT WITH PRELIMINARY RESULTS – I identify the long-run spatial effects of an exogenous decline in the capital stock on population growth and sectoral change. After WWII, South Austria has been the only region in entire Europe that was initially liberated but not permanently occupied by the Red Army. The demarcation line between the liberation forces was fully exogenous, solely driven by the respective velocity of their jeeps. I use the liberation and the 77 days lasting temporary occupation of Styria after WWII to estimate causal inferences of dismantling and pillaging activities by both the Red Army and its soldiers. First estimates with a sample of direct demarcation line border municipalities indicate a relative population decline of Red Army liberated municipalities of around 15% compared to direct adjacent municipalities. In contrast, pre-WWII population growth shows no differences. A panel from 1934 to 2011 with demographic and economic variables will be constructed. A Re- gression Discontinuity approach will be employed to estimate discontinuities across the tempo- rary demarcation line on population dynamics and on sectoral change during the last eight dec- ades. JEL-Codes: J11, N14, N94, R12, R23 Keywords: Regional Economic Activity, Regional Spillovers, Dismantling, Austria Christian Ochsner Ifo Institute – Leibniz Institute for Economic Research at the University of Munich Dresden Branch Einsteinstr. 3 01069 Dresden, Germany Phone: +49(0)351/26476-26 [email protected] This version: March 2017 1 1. Introduction (and first results) Economic activity is unequally distributed across space. -

Building an Unwanted Nation: the Anglo-American Partnership and Austrian Proponents of a Separate Nationhood, 1918-1934

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Carolina Digital Repository BUILDING AN UNWANTED NATION: THE ANGLO-AMERICAN PARTNERSHIP AND AUSTRIAN PROPONENTS OF A SEPARATE NATIONHOOD, 1918-1934 Kevin Mason A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of PhD in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2007 Approved by: Advisor: Dr. Christopher Browning Reader: Dr. Konrad Jarausch Reader: Dr. Lloyd Kramer Reader: Dr. Michael Hunt Reader: Dr. Terence McIntosh ©2007 Kevin Mason ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Kevin Mason: Building an Unwanted Nation: The Anglo-American Partnership and Austrian Proponents of a Separate Nationhood, 1918-1934 (Under the direction of Dr. Christopher Browning) This project focuses on American and British economic, diplomatic, and cultural ties with Austria, and particularly with internal proponents of Austrian independence. Primarily through loans to build up the economy and diplomatic pressure, the United States and Great Britain helped to maintain an independent Austrian state and prevent an Anschluss or union with Germany from 1918 to 1934. In addition, this study examines the minority of Austrians who opposed an Anschluss . The three main groups of Austrians that supported independence were the Christian Social Party, monarchists, and some industries and industrialists. These Austrian nationalists cooperated with the Americans and British in sustaining an unwilling Austrian nation. Ultimately, the global depression weakened American and British capacity to practice dollar and pound diplomacy, and the popular appeal of Hitler combined with Nazi Germany’s aggression led to the realization of the Anschluss . -

Zur Geschichte Der Feuerwehr in Mariahilf

Zur Geschichte der Feuerwehr in Mariahilf Zur Geschichte der Berufsfeuerwehr in Wien Monarchie1 Das genaue Gründungsdatum der Wiener Berufsfeuerwehr ist nicht bekannt. In einer aus dem Jahr 1686 stammenden Instruktion eines Herrn Unterkämmerers bei Gem. Wien wird die Entlohnung von vier Feuerknechten mit zwei Gulden Wochenlohn erwähnt. Dieses Jahr gilt daher als Gründungsjahr der Wiener Feuerwehr. Im Brandfall wurden diese vier Männer aus Handwerkern, vor allem von Zimmerleuten und Rauchfangkehrern, rekrutiert. Ansonsten standen sie der Stadt Wien für handwerkliche Arbeiten zur Verfügung. Stationiert waren sie im Unter- kammeramt Am Hof 9. Kaiser Leopold I. (1688) und Maria Theresia (1759) erließen neue Feuerlösch- ordnungen. Maria Theresia verstärkte außerdem den Mannschaftsstand und das Personal wurde ständig angestellt. Seit 1527 hatte der Türmer des Stephansdoms den Auftrag, mit einer roten Fahne beziehungsweise einer roten Laterne jene Richtung anzuzeigen, in der er einen Brand entdeckt hatte. Ein bis dahin verwendetes Sprechrohr wurde 1836 durch ein Blechrohr ersetzt, in dem verschraubbare Beinkugeln mit einer geschriebenen Nach- richt darin nach unten rollten, um dann weiter zur Löschanstalt Am Hof gebracht zu werden. Im Jahr 1855 wurde eine Telegrafenverbindung zwischen der Türmerstube und der Zentrallöschanstalt Am Hof eingerichtet. 1866 wurde der Türmer auf dem Südturm des Stephansdoms durch Feuerwehrmänner e- rsetzt, die für diesen Dienst eine Zulage erhielten. Dampfspritze. Bildquelle: Annelies Umlauf-Lamatsch, Traraaa…. Die Feuerwehr! Grafik Kurt Röschl. Bezirksmuseum Mariahilf Das Jahr 1786 brachte die Uniformierung der Löschmannschaften. Ihnen wurde die Stadtlivree (langer weißer Zwilchrock, lange weiße Zwilchhose, schwarzer Zylinder mit Stadtwappen) zuerkannt. Diese Uniform wurde bis 1854 getragen. Dann erfolgte der Wechsel zu einer Uniform mit militärischem Schnitt: schwarze Hose, blaue Bluse, 1 Wikipedia 2012 2 schwarze Lederstiefel.