Report for Austria– Questionnaire Related the Administration Control

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Fundamentals of Constitutional Courts

Constitution Brief April 2017 Summary The Fundamentals of This Constitution Brief provides a basic guide to constitutional courts and the issues that they raise in constitution-building processes, and is Constitutional Courts intended for use by constitution-makers and other democratic actors and stakeholders in Myanmar. Andrew Harding About MyConstitution 1. What are constitutional courts? The MyConstitution project works towards a home-grown and well-informed constitutional A written constitution is generally intended to have specific and legally binding culture as an integral part of democratic transition effects on citizens’ rights and on political processes such as elections and legislative and sustainable peace in Myanmar. Based on procedure. This is not always true: in the People’s Republic of China, for example, demand, expert advisory services are provided it is clear that constitutional rights may not be enforced in courts of law and the to those involved in constitution-building efforts. constitution has only aspirational, not juridical, effects. This series of Constitution Briefs is produced as If a constitution is intended to be binding there must be some means of part of this effort. enforcing it by deciding when an act or decision is contrary to the constitution The MyConstitution project also provides and providing some remedy where this occurs. We call this process ‘constitutional opportunities for learning and dialogue on review’. Constitutions across the world have devised broadly two types of relevant constitutional issues based on the constitutional review, carried out either by a specialized constitutional court or history of Myanmar and comparative experience. by courts of general legal jurisdiction. -

Sources for Genealogical Research at the Austrian War Archives in Vienna (Kriegsarchiv Wien)

SOURCES FOR GENEALOGICAL RESEARCH AT THE AUSTRIAN WAR ARCHIVES IN VIENNA (KRIEGSARCHIV WIEN) by Christoph Tepperberg Director of the Kriegsarchiv 1 Table of contents 1. The Vienna War Archives and its relevance for genealogical research 1.1. A short history of the War Archives 1.2. Conditions for doing genealogical research at the Kriegsarchiv 2. Sources for genealogical research at the Kriegsarchiv 2. 1. Documents of the military administration and commands 2. 2. Personnel records, and records pertaining to personnel 2.2.1. Sources for research on military personnel of all ranks 2.2.2. Sources for research on commissioned officers and military officials 3. Using the Archives 3.1. Regulations for using personnel records 3.2. Visiting the Archives 3.3. Written inquiries 3.4. Professional researchers 4. Relevant publications 5. Sources for genealogical research in other archives and institutions 5.1. Sources for genealogical research in other departments of the Austrian State Archives 5.2. Sources for genealogical research in other Austrian archives 5.3. Sources for genealogical research in archives outside of Austria 5.3.1. The provinces of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy and its “successor states” 5.3.2. Sources for genealogical research in the “successor states” 5.4. Additional points of contact and practical hints for genealogical research 2 1. The Vienna War Archives and its relevance for genealogical research 1.1. A short history of the War Archives Today’s Austrian Republic is a small country, but from 1526 to 1918 Austria was a great power, we can say: the United States of Middle and Southeastern Europe. -

Austerity and the Rise of the Nazi Party Gregori Galofré-Vilà, Christopher M

Austerity and the Rise of the Nazi party Gregori Galofré-Vilà, Christopher M. Meissner, Martin McKee, and David Stuckler NBER Working Paper No. 24106 December 2017, Revised in September 2020 JEL No. E6,N1,N14,N44 ABSTRACT We study the link between fiscal austerity and Nazi electoral success. Voting data from a thousand districts and a hundred cities for four elections between 1930 and 1933 shows that areas more affected by austerity (spending cuts and tax increases) had relatively higher vote shares for the Nazi party. We also find that the localities with relatively high austerity experienced relatively high suffering (measured by mortality rates) and these areas’ electorates were more likely to vote for the Nazi party. Our findings are robust to a range of specifications including an instrumental variable strategy and a border-pair policy discontinuity design. Gregori Galofré-Vilà Martin McKee Department of Sociology Department of Health Services Research University of Oxford and Policy Manor Road Building London School of Hygiene Oxford OX1 3UQ & Tropical Medicine United Kingdom 15-17 Tavistock Place [email protected] London WC1H 9SH United Kingdom Christopher M. Meissner [email protected] Department of Economics University of California, Davis David Stuckler One Shields Avenue Università Bocconi Davis, CA 95616 Carlo F. Dondena Centre for Research on and NBER Social Dynamics and Public Policy (Dondena) [email protected] Milan, Italy [email protected] Austerity and the Rise of the Nazi party Gregori Galofr´e-Vil`a Christopher M. Meissner Martin McKee David Stuckler Abstract: We study the link between fiscal austerity and Nazi electoral success. -

Austria FULL Constitution

AUSTRIA THE FEDERAL CONSTITUTIONAL LAW OF 1920 as amended in 1929 as to Law No. 153/2004, December 30, 2004 Table of Contents CHAPTER I General Provisions European Union CHAPTER II Legislation of the Federation CHAPTER III Federal Execution CHAPTER IV Legislation and Execution by the Länder CHAPTER V Control of Accounts and Financial Management CHAPTER VI Constitutional and Administrative Guarantees CHAPTER VII The Office of the People’s Attorney ( Volksanwaltschaft ) CHAPTER VIII Final Provisions CHAPTER I General Provisions European Union A. General Provisions Article 1 Austria is a democratic republic. Its law emanates from the people. Article 2 (1) Austria is a Federal State. (2) The Federal State is constituted from independent Länder : Burgenland, Carinthia, Lower Austria, Upper Austria, Salzburg, Styria, Tirol, Vorarlberg and Vienna. Article 3 (1) The Federal territory comprises the territories ( Gebiete ) of the Federal Länder . (2) A change of the Federal territory, which is at the same time a change of a Land territory (Landesgebiet ), just as the change of a Land boundary inside the Federal territory, can—apart from peace treaties—take place only from harmonizing constitutional laws of the Federation (Bund ) and the Land , whose territory experiences change. Article 4 (1) The Federal territory forms a unitary currency, economic and customs area. (2) Internal customs borders ( Zwischenzollinien ) or other traffic restrictions may not be established within the Federation. Article 5 (1) The Federal Capital and the seat of the supreme bodies of the Federation is Vienna. (2) For the duration of extraordinary circumstances the Federal President, on the petition of the Federal Government, may move the seat of the supreme bodies of the Federation to another location in the Federal territory. -

Presentation Greece En.Pdf

ASSOCIATION INTERNATIONALE DES HAUTES JURIDICTIONS ADMINISTRATIVES INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF SUPREME ADMINISTRATIVE JURISDICTIONS Presentation form Name of the Court: Council of State Name of the President/Chief Justice: Aikaterini Sakellaropoulou Address:47-49, Panepistimiou Av. Phone number : (+ 30) 2132102098 Fax: (+ 30) 2132102097 Website: www.adjustice.gr E-mail: [email protected] 1. NATIONAL JUDICIAL ORGANISATION 1.1. General presentation of the judicial organisation and position of the administrative jurisdictional order In Greece there is a distinction between the administrative courts on the one hand and the civil and criminal courts on the other (Article 93 (1) of the Constitution). The organisation of the two jurisdictional orders follows the classic pyramidal form in this matter: at the top of the civil and criminal jurisdictions is the Court of Cassation; then the courts of appeal and the courts of first instance; finally, at the base of the pyramid, justice of peace. At the head of the administrative jurisdiction is the Council of State; then the administrative courts of appeal and the administrative tribunals of first instance. The third supreme court, the Court of Audits knows, sovereignly, certain specific administrative disputes (listed in Article 98 of the Constitution). Disputes of attribution are settled by a Special Supreme Court (Article 100 of the Constitution). 1.2. Key dates in the evolution of the administrative jurisdictional order and the control of administrative acts The creation of administrative tribunals was provided for in Greece as early as 1833. The Court of Audits was first established as an administrative body competent in certain administrative disputes submitted to it. -

1 Different Models for Protection of Constitutionality, Legality And

Prof. Tanja Karakamisheva-Jovanovska, Ph.D 1 Different Models for Protection of Constitutionality, Legality and Independence of Constitutional Court of the Republic of Macedonia 1. About the different models of protection of constitutionality and legality The Constitutional Court is a separate body that serves as a watchdog of the constitution in a given country, and as a protector of the constitutionality, legality, and the citizens' freedoms and rights within the national legal system. From an organisational point of view, there are several models of constitutionality that can be determined, as follows: 1. American model based on the Marbery vs. Madison case (Marbery vs. Madison, 1803) , and, in accordance with the John Marshal doctrine, according to whom the constitutional issues are subject of interest and resolution of all courts that are under the scope of the regular judiciary (in an environment of decentralised, widespread of dispersed control procedure), and based on organisational procedure that is typical for the regular judiciary (incidenter). And while the American model with widespread system of protection of constitutionality gives the authority to all courts to assess the constitutionality of the laws, the European model concentrates all the power for the assessment of the constitutionality on one body. In Europe, there are number of countries that have accepted the American model, such as Denmark, Estonia, Ireland, Norway, Sweden, and in North America, besides the U.S., this model is also applied in Canada, as well as, on the African continent, in Botswana, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Kenya and other countries. 2 1 Associate Professor for Constitutional Law and Political System at the University "Sc. -

Constitutional Courts Versus Supreme Courts

SYMPOSIUM Constitutional courts versus supreme courts Lech Garlicki* Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/icon/article/5/1/44/722508 by guest on 30 September 2021 Constitutional courts exist in most of the civil law countries of Westem Europe, and in almost all the new democracies in Eastem Europe; even France has developed its Conseil Constitutionnel into a genuine constitutional jurisdiction. While their emergence may be regarded as one of the most successful improvements on traditional European concepts of democracy and the rule of law, it has inevitably given rise to questions about the distribution of power at the supreme judicial level. As constitutional law has come to permeate the entire structure of the legal system, it has become impossible to maintain a fi rm delimitation between the functions of the constitutional court and those of ordinary courts. This article looks at various confl icts arising between the higher courts of Germany, Italy, Poland, and France, and concludes that, in both positive and negative lawmaking, certain tensions are bound to exist as a necessary component of centralized judicial review. 1 . The Kelsenian model: Parallel supreme jurisdictions 1.1 The model The centralized Kelsenian system of judicial review is built on two basic assu- mptions. It concentrates the power of constitutional review within a single judicial body, typically called a constitutional court, and it situates that court outside the traditional structure of the judicial branch. While this system emerged more than a century after the United States’ system of diffused review, it has developed — particularly in Europe — into a widely accepted version of constitutional protection and control. -

Austria: Vienna

Guide to Catholic-Related Records outside the U.S. about Native Americans See User Guide for help on interpreting entries Archdiocese of Vienna new 2004 AUSTRIA, VIENNA Archdiocese of Vienna Archives AT- 2 A-1010 Wollzeile 2 Wien, Oesterreich Phone 43 1 51552 http://stephanscom.at/ Hours: Monday, Tuesday, and Thursday, 8:30-1:00, 2:00-4:00; and Friday, 8:30-12:00 Access: Some restrictions apply Copying facilities: Yes History of the Leopoldine Society 1827 Bishop Edward D. Fenwick, O.P. of Cincinnati, Ohio sent Reverend John Fréderic Résé to Europe to recruit German- speaking priests and financial assistance for the Cincinnati Diocese; Reverend Samuel Mazzuchelli, O.P. (1806-1864) was among those recruited 1829 In response, the Leopoldine Society (Leopoldinen Stetiftung) was established in Vienna with headquarters at the Augustinian monastery; it solicited German- speaking priests and financial assistance from the dioceses of the Austrian Empire for needy dioceses in the United States, some of which had American Indian missions 1830-1910 The Leopoldine Society donated about $680,500 (3,402,000 kronen) to U.S. dioceses; those with Indian missions that received notable funding included Boise, Cincinnati, Detroit, Grand Rapids, Green Bay, Lead (later renamed Rapid City), Marquette, Nesqually (later renamed Seattle), Oregon (later renamed Portland in Oregon), and Tucson Before 1850 Due to efforts by the Leopoldine Society, several priests from the Austrian Empire emigrated to the United States; those who became missionaries to American Indians include Reverend Frederic I. Baraga (first bishop of the Diocese of Marquette, Michigan), Reverend Joseph F. Buh, Reverend Ignatius Mrak (second bishop of the Diocese of Marquette, Michigan), Reverend Francis Pierz, and Reverend Otto Skolla, O.F.M. -

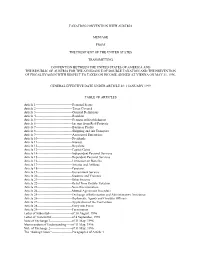

Taxation Convention with Austria Message from The

TAXATION CONVENTION WITH AUSTRIA MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES TRANSMITTING CONVENTION BETWEEN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA AND THE REPUBLIC OF AUSTRIA FOR THE AVOIDANCE OF DOUBLE TAXATION AND THE PREVENTION OF FISCAL EVASION WITH RESPECT TO TAXES ON INCOME, SIGNED AT VIENNA ON MAY 31, 1996. GENERAL EFFECTIVE DATE UNDER ARTICLE 28: 1 JANUARY 1999 TABLE OF ARTICLES Article 1----------------------------------Personal Scope Article 2----------------------------------Taxes Covered Article 3----------------------------------General Definitions Article 4----------------------------------Resident Article 5----------------------------------Permanent Establishment Article 6----------------------------------Income from Real Property Article 7----------------------------------Business Profits Article 8----------------------------------Shipping and Air Transport Article 9----------------------------------Associated Enterprises Article 10--------------------------------Dividends Article 11--------------------------------Interest Article 12--------------------------------Royalties Article 13--------------------------------Capital Gains Article 14--------------------------------Independent Personal Services Article 15--------------------------------Dependent Personal Services Article 16--------------------------------Limitation on Benefits Article 17--------------------------------Artistes and Athletes Article 18--------------------------------Pensions Article 19--------------------------------Government Service Article 20--------------------------------Students -

Low Fertility in Austria and the Czech Republic: Gradual Policy Adjustments

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Sobotka, Tomáš Working Paper Low fertility in Austria and the Czech Republic: Gradual policy adjustments Vienna Institute of Demography Working Papers, No. 2/2015 Provided in Cooperation with: Vienna Institute of Demography (VID), Austrian Academy of Sciences Suggested Citation: Sobotka, Tomáš (2015) : Low fertility in Austria and the Czech Republic: Gradual policy adjustments, Vienna Institute of Demography Working Papers, No. 2/2015, Austrian Academy of Sciences (ÖAW), Vienna Institute of Demography (VID), Vienna This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/110987 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten -

2017 Edition of the Comprehensive Plan

FAIRFAX COUNTY COMPREHENSIVE PLAN, 2017 Edition AREA II Vienna Planning District, Amended through 2-23-2021 Overview Page 1 VIENNA PLANNING DISTRICT OVERVIEW OVERVIEW The Vienna Planning District encompasses approximately 12,000 acres, or about five percent of the county. The planning district is located in the central northeast section of the county, and is generally bordered to the east by Leesburg Pike (Route 7), the Capital Beltway/Interstate 495 (I-495), Interstate 66 (I-66), and Prosperity Avenue, and to the west by Hunter Mill Road, Blake Lane, and the Difficult Run Stream Valley (see Figure 1). The planning district contains the Town of Vienna, the Vienna Transit Station Area (TSA) and portions of the Merrifield Suburban Center and the Tysons Urban Center. Plan recommendations for the Merrifield Suburban Center are included in the Area I volume of the Comprehensive Plan, Merrifield Suburban Center. Plan recommendations for the Tysons Urban Center are included in the Area II volume of the Comprehensive Plan, Tysons Urban Center. The Town of Vienna has jurisdiction over its own planning functions. Consult the Town of Vienna Comprehensive Plan for recommendations within this area. The planning district is predominantly comprised of single-family neighborhoods. The exceptions to this are areas within the Vienna TSA, Merrifield Suburban Center, and the Tysons Urban Center. The planning district is traversed by several major roads and highways, including I-495, I-66, the Dulles Airport Access Road and Dulles Toll Road (DAAR, Route 267), Lee Highway (Route 29), Arlington Boulevard (Route 50), Leesburg Pike, and Chain Bridge Road (Route 123). -

The Guarantees of the Independence of the Constitutional Court

The Guarantees of the Independence of the Constitutional Court Together with the representative and executive Branches, judicial authority is the independent and fully legitimate branch within the governmental system, organized on the basis of the classical principle of the separation of powers. Georgian Constitution dedicates a separate chapter to the judicial power, which declares the independence of the judicial power. “The judiciary shall be independent and exercised exclusively by courts. A court shall adopt a judgment in the name of Georgia.” 1 According to the Constitution, the judicial body of the constitutional review is the Constitutional Court of Georgia. 2 Despite of its relatively short period of existence – 14 years of exercising its’ powers -, the Constitutional Court of Georgia is a major institution within the separation of powers system, which ensures the constitutional balance and the protection of the constitutionally recognized human rights and freedoms as well as the development of the stabile government in the country. Of course, there is much more time needed, thus there is much more to be done in order to improve its’ efficiency. This cannot be achieved without the proper development of the legal culture and the traditions in the country. This very important democratic institution of the constitutional control was established by the Georgian Constitution on the 24 th of August in 1995. The fundamental principles of its formation, functioning and the legal status are established in the Constitution. These fundamental issues were further elaborated in the organic “Law on the Constitutional Legal Proceedings” on the 21st of March 1996 and by the rules of the Constitutional Court.