Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

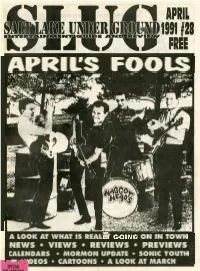

April's Fools

APRIL'S FOOLS ' A LOOK AT WHAT IS REAL f ( i ON IN. TOWN NEWS VIEWS . REVIEWS PREVIEWS CALENDARS MORMON UPDATE SONIC YOUTH -"'DEOS CARTOONS A LOOK AT MARCH frlday, april5 $7 NOMEANSNO, vlcnms FAMILYI POWERSLAVI saturday, april 6 $5 an 1 1 piece ska bcnd from cdlfomb SPECKS witb SWlM HERSCHEL SWIM & sunday,aprll7 $5 from washln on d.c. m JAWBO%, THE STENCH wednesday, aprl10 KRWTOR, BLITZPEER, MMGOTH tMets $10raunch, hemmetal shoD I SUNDAY. APRIL 7 I INgTtD, REALITY, S- saturday. aprll $5 -1 - from bs aqdes, califomla HARUM SCAIUM, MAG&EADS,;~ monday. aprlll5 free 4-8. MAtERldl ISSUE, IDAHO SYNDROME wedn apri 17 $5 DO^ MEAN MAYBE, SPOT fiday. am 19 $4 STILL UFEI ALCOHOL DEATH saturday, april20 $4 SHADOWPLAY gooah TBA mday, 26 Ih. rlrdwuhr tour from a land N~AWDEATH, ~O~LESH;NOCTURNUS tickets $10 heavy metal shop, raunch MATERIAL ISSUE I -PRIL 15 I comina in mayP8 TFL, TREE PEOPLE, SLaM SUZANNE, ALL, UFT INSANE WARLOCK PINCHERS, MORE MONDAY, APRIL 29 I DEAR DICKHEADS k My fellow Americans, though:~eopledo jump around and just as innowtiwe, do your thing let and CLIJG ~~t of a to NW slam like they're at a punk show. otherf do theirs, you sounded almost as ENTEIWAINMENT man for hispoeitivereviewof SWIM Unfortunately in Utah, people seem kd as L.L. "Cwl Guy" Smith. If you. GUIIBE ANIB HERSCHELSWIMsdebutecassette. to think that if the music is fast, you are that serious, I imagine we will see I'mnotamemberofthebancljustan have to slam, but we're doing our you and your clan at The Specks on IMVIEW avid ska fan, and it's nice to know best to teach the kids to skank cor- Sahcr+nightgiwingskrmkin'Jessom. -

Their Lived Experience in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit Andrea Prentiss Baptist Hospital of Miami, [email protected]

Baptist Health South Florida Scholarly Commons @ Baptist Health South Florida All Publications 2014 Hearing the Child's Voice: Their Lived Experience in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit Andrea Prentiss Baptist Hospital of Miami, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.baptisthealth.net/se-all-publications Part of the Critical Care Nursing Commons, Maternal, Child Health and Neonatal Nursing Commons, and the Pediatrics Commons Citation Prentiss, Andrea, "Hearing the Child's Voice: Their Lived Experience in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit" (2014). All Publications. 649. https://scholarlycommons.baptisthealth.net/se-all-publications/649 This Article -- Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons @ Baptist Health South Florida. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons @ Baptist Health South Florida. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida HEARING THE CHILD’S VOICE: THEIR LIVED EXPERIENCE IN THE PEDIATRIC INTENSIVE CARE UNIT A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in NURSING by Andrea S. Prentiss 2014 To: Dean Ora Lea Strickland Nicole Wertheim College of Nursing & Health Sciences This dissertation, written by Andrea S. Prentiss entitled Hearing the Child’s Voice: Their Lived Experience in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this dissertation and recommend that it be approved. _______________________________________ Dionne Stephens _______________________________________ Jean Hannan _______________________________________ Dorothy Brooten _______________________________________ JoAnne Youngblut, Major Professor Date of Defense: November 12, 2014 The dissertation of Andrea S. -

2011-11-25 1. När Det Är Spelning På Nuclear Nation Brukar Det Komma

Nuclear Nation Quiz - 2011-11-25 1. När det är spelning på Nuclear Nation brukar det komma mycket folk. Det gör det ibland även annars och då kan det bli långa köer som ringlar sig runt Linköping. Under tidigt 2000-tal kunde NN- besökare vid ett festtillfälle slippa kötristeseen och gå direkt in på festen förutsatt att de uppfyllde ett krav. Vad skulle två NN-besökare göra för att få gå före i kön? A: Bära likadana kläder B: Kunna texten till Headhunter utantill och sjunga den tvåstämmigt C: Vara fastkedjade i varandra 2. Ni befinner er just nu på synthquiz med den anrika synthföreningen Nuclear Nation, men det var inte helt självklart att vi skulle heta just så. Vilket annat namn fanns som förslag? A: Eclipse B: Solaris C: SUN 3. Apoptygma Berzerk gjorde 98 en spelning i Leipzig från vilken i alla fall en liten del kom med på skivan APBL98. Trots att bandet körde på som hårdast med en Depeche-cover som folk verkade uppskatta, så fick spelningen ett snöpligt slut. Men vad hände? A: Det utbröt en mindre en brand i ljudteknikerbåset pga. underdimensionerade elkablar. B: Spelningen råkade äga rum samma kväll som kraftverket Holzkohle fallerade, vilket ledde till Leipzigs hittills största elavbrott. C: Trots att Apoptygma ville köra en låt till, så stängde polisen ner konserten i förtid. 4. En inställd spelning är också en spelning brukar man säga och ett band som skulle ha spelat på NN för ett antal år sedan, men som tyvärr fick ställa in p.g.a. sjukdom var... ja, vilket band då? A: Covenant B: VNV Nation C: Tyskarna från Lund 5: Ett band som dock har spelat på NN är LOWE. -

Black Monday Magazine

5333 north lincoln avenue #3n chicago illinois 60625 black mon day START v1.4 day mon black :::BLACK MONDAY V1.4::: controlled bleeding noise unit advertise (it’s very affordable!) windsdieddownadifferen controlled bleedingnoiseunitadvertise (it’s advertise (it’s very affordable!) windsdieddownadifferent advertise kindofcopthetablesecular (it’s my lifewiththethrillkillkult sistermachinegunslaveunitkraftwelt beautyw acumen alienfaktor battery collide controlledbleedingnoiseunitadvert noise unit advertise (it’s very affordable!) windsdieddownadifferent noise unitadvertise kindofcoptheta (it’s able!) vault.9rosettastoneseveredheadstherazorskylinegrotuskmfdm grotusdown kmfdm a different kind my of verylife affordable!) mechanism insight23 christanaloguevampirerodentsadvertise (it’s cop with the thrill the kill table kult secularsister machine mechanism gun insightslave unit23 kraftchristwelt analogu e beauty vampire wired rodents under advertise the noise (it’s very affordable!) advertise (it’s very vault.9 affordable!) rosetta stone16 volt christ analogue vampire rodents advertise (it’s very affordable!) vault.9rosetta stone christ analoguevampirerodentsadvertise (it’s kraftwelt beauty wired under the noise advertise (it’s very affordable!) 16volt kraftwelt beautywiredunderthenoiseadvertise (it’s slave unit kraftwelt beauty wired under the noise advertise (it’s very affordable! slave unitkraftweltbeautywired under thenoiseadvertise (it’s pire rodents advertise (it’s very affordable!) vault.9rosettastoneseveredheads pire rodentsadvertise -

Environmental Impact Assessment

SFG1219 v3 World Bank-financed Integrated Economic Development of Small Towns Project (IEDSTP)in Xiantang Town Dongyuan County,Heyuan City Environmental Impact Assessment Xiantang town Government in Dongyuan County Guangzhou Research Institute of Environment Protection June 2015 - 1 - Abbreviations and Acronyms CSEE Construction Supervision Environmental Engineer CDD Community Driven Development DI Design Institute EA Environmental Assessment EIA Environmental Impact Assessment EMP Environmental Management Plan EMS Environmental Monitoring Station EPB Environmental Protection Bureau EMC Enviornmental Management Coordinator IA Implementation Agency MEP Ministry of Environmental Protection PO Project Owner PMO Project Management Office PRC The People's Republic ofChina SE Supervision Engineer TOR Terms of Reference WB World Bank XIEDTSP World Bank-funded Xiantang Integrated Economic Development of Small Towns Project CURRENCIES & OTIIER UNITS MU Area Unit (JMU=O.0667hm2) RMB Chinese Yuan (Renminbi) USD United States Dollar Exchange rate 1 USD=6.78 RMB CHEMICAL ABBREVIATIONS BOD5 Biochemical Oxygen Demand (5 days) COD Chemical Oxygen Demand CODMn Permanganate Index NH3-N Ammonia Nitrogen SS Suspended Solids TN Total Nitrogen TP Total Phosphorus TSP Total Suspended Particulates TSS Total Suspended Solids Leq Equivalent Continuous Noise Level - 2 - Contents 1 General ................................................................................................................................ - 1 - 1.1 Project Overview ..................................................................................................... -

High-Speed Ground Transportation Noise and Vibration Impact Assessment

High-Speed Ground Transportation U.S. Department of Noise and Vibration Impact Assessment Transportation Federal Railroad Administration Office of Railroad Policy and Development Washington, DC 20590 Final Report DOT/FRA/ORD-12/15 September 2012 NOTICE This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Government assumes no liability for its contents or use thereof. Any opinions, findings and conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the United States Government, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the United States Government. The United States Government assumes no liability for the content or use of the material contained in this document. NOTICE The United States Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. Trade or manufacturers’ names appear herein solely because they are considered essential to the objective of this report. REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188), Washington, DC 20503. -

Front Line Assembly - Bio

FRONT LINE ASSEMBLY - BIO Front Line Assembly is the primary focus of Vancouver-based musician Bill Leeb. A founding member of Skinny Puppy, Leeb moved on to form FLA in 1986 with Michael Balch, releasing some cassettes (since released as Total Terror I & II) which paved the way for their 1987 releases: The Initial Command, State of Mind, and Corrosion. In late 1988, they recorded the mini-LP Disorder, since combined with Corrosion and released as Corroded Disorder. Their 1989 release, Gashed Senses and Crossfire, further cemented their popularity in the industrial scene, and prompted their first world tour. By 1990, Balch had departed and Rhys Fulber rounded out the duo, releasing Caustic Grip. But it was two years later when the duo released the classic album, Tactical Neural Implant, which has become for many, the genre's crowning moment. To this day, TNI still defines the best of industrial music. FLA enraged many of their fans in 1994 when they began to experiment with their established electronic-only sound. Millenium, with its heavy doses of live and sampled metal guitars, dared its audience to grow and expand with the band beyond industrial's perceived barriers. Front Line stepped to the firing line again in 1995 with Hard Wired, which reflected both a return to form and a continued embracing of the guitar. Hard Wired not only picked up where Implant left off, it improved on the sound by adding in elements of all of their side projects. A fall European tour was recorded for the 1996 release Live Wired, their first concert CD ever. -

What Lay in Front of Us Was Unlike Anything I Ever Had Imagined: It Was

story= _ "What lay in front of us was unlike anything I ever had imagined: it was not simply a small valley guarding its green life from the scorching suns, but rather an endless expanse of vegetated lands. It was like being home again... No — the scenery was more akin to a dreamland conjured from the memories of a long gone age. The Lady of Light had not seen such a landscape for hundreds, thousands, perhaps millions, of years, and she rejoiced at the view while the fresh northern winds blew in her face. The dwarves, on the other hand, were too used to their underground abodes to feel at ease on the surface. I understood them, and regretted that we could not have their company for our next journey. The prospect of marching into the northern humans’ territory uninvited was not very encouraging." Was vor uns lag, war anders als alles, was ich mir je vorgestellt hatte: Es war nicht nur ein kleines Tal, das sein grünes Leben vor den sengenden Sonnen bewahrte, sondern vielmehr eine endlose Weite an bewachsenem Land. Es war, als wäre man wieder zu Hause..... Nein - die Landschaft glich eher einem Traumland, das aus den Erinnerungen einer längst vergangenen Zeit entstanden war. Die Herrin des Lichts hatte eine solche Landschaft seit Hundert, Tausenden, vielleicht Millionen von Jahren nicht mehr gesehen, und sie freute sich über die Aussicht, während die frischen Nordwinde in ihr Gesicht wehten. Die Zwerge hingegen waren zu sehr an ihre unterirdischen Behausungen gewöhnt, um sich an der Oberfläche wohl zu fühlen. Ich verstand sie und bedauerte, dass wir ihre Gesellschaft für unsere nächste Reise nicht zur Verfügung hatten. -

Kankyō Ongaku

Dead Oceans DURAND JONES & THE INDICATIONS American Love Call About the album Details Durand Jones & the Indications aren’t looking backwards. Helmed by foil CATALOG NUMBER: DOC177 vocalists in Durand Jones and drummer Aaron Frazer, the Indications conjure RELEASE DATE: March 1, 2019 the dynamism of Jackie Wilson, Curtis Mayfield, AND the Impressions. Even FORMAT: CD/Color LP GENRE: R&B / Soul with an aesthetic steeped in the golden, strings-infused dreaminess of early KEY MARKETS: Los Angeles, SF-Oakland-SJ, New York, ‘70s soul, the Indications’ sophomore LP, American Love Call, is planted Indianapolis, Cincinatti, Chicago, Portland, Austin, firmly in the present, with the urgency of this moment in time. Seattle TERRITORY RESTRICTIONS: None The Indications’ 2016 self-titled debut was the product of friends who met VINYL NOT RETURNABLE as students at Indiana University in Bloomington, In., recorded for $452.11, including a case of beer. American Love Call, the band’s sophomore LP is instead the record the Indications dreamed of making, fleshed out with strings, backing vocals, and a newfound confidence in songwriting. CD UPC: LP UPC: DIGITAL UPC: Blending a slew of influences from years spent crate-digging, guitarist 656605147727 656605147734 656605147765 Blake Rhein says the Indications approach songs in the same way hip-hop producers do, as likely to pull inspiration from ‘70s folk-rock or classic R&B as they are Nas’ Illmatic. “Did I expect to do this shit once I got out of college? Hell no,” Jones relays, 6 56605 14772 7 6 56605 14773 4 6 56605 14776 5 laughing. -

Illinois Classical Studies

UMVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN CLASSICS The person charging this material is re- sponsible for its return to the library from which it was withdrawn on or before the Latest Date stamped below. Theft, mutilation, and underlining of books are reasons for disciplinary action and may result in dismissal from the University. To renew call Telephone Center, 333-8400 UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN JUL i G !S:ig OCT 1 1 ?(05 L161—O-1096 L<(TL--VJA-<.\J^ ILLINOIS CLASSICAL STUDIES VOLUME IX. 1 SPRING 1984 J. K. Newman, Editor ISSN 0363-1923 1 1 ILLINOIS CLASSICAL STUDIES VOLUME IX. Spring 1 984 J. K. Newman, Editor Patet omnibus Veritas; nondum est occupata; multum ex ilia etiam futuris relictum est. Sen. Epp. 33. 1 SCHOLARS PRESS ^^-^ ISSN 0363-1923 ^9^^ 1 ILLINOIS CLASSICAL STUDIES VOLUME IX. ©1984 Scholars Press 101 Salem Street P.O. Box 2268 Chico, California 95927 Printed in the U.S.A. ADVISORY EDITORIAL COMMITTEE John J. Bateman Howard Jacobson Harold C. GotofF David Sansone Responsible Editor: J. K. Newman The Editor welcomes contributions, which should not normally exceed twenty double-spaced typed pages, on any topic relevant to the elucidation of classical antiquity, its transmission or influence. Con- sistent with the maintenance of scholarly rigor, contributions are especially appropriate which deal with major questions of interpre- tation, or which are likely to interest a wider academic audience. Care should be taken in presentation to avoid technical jargon, and the trans-rational use of acronyms. Homines cum hominibus loquimur. Contributions should be addressed to: The Editor, Illinois Classical Studies, Department of the Classics, 4072 Foreign Languages Building, 707 South Mathews Avenue, Urbana, Illinois 61801 Each contributor receives twenty-five offprints. -

October 2016 New Releases What’S Featured Exclusives PAGE Inside

October 2016 New Releases what’s featured exclusives PAGE inside Music 3 RUSH Releases Available Immediately! 71 DVD & Blu-ray Music Video DVD & Blu-ray 3 FEATURED RELEASES Non-Music Video DVD & Blu-ray 9 Vinyl MORPHINE - JOURNEY BRIDE OF RE-ANIMATOR PORTLANDIA: SEASON 6 Audio 29 OF DREAMS PAGE 12 PAGE 23 CD PAGE 5 Audio 35 MVD Distribution Independent Releases 63 Order Form 76 Deletions and Price Changes 74 ARCHERS OF LOAF - VAN DER GRAAF ELECTRIC SIX - FRESH 800.888.0486 CURSE OF THE LOAF: GENERATOR - DO NOT BLOOD FORTIRED LIMITED EDITION 2LP... DISTURB... VAMPYRES LIMITED VINYL 203 Windsor Rd., Pottstown, PA 19464 www.MVDb2b.com PAGE 28 PAGE 34 PAGE 43 MORPHINE - THE TUBES - DON MCLEAN - JOURNEY OF DREAMS LIVE AT GERMAN TELEVISION: THE STARRY STARRY NIGHT Mr. Sandman, bring me a JOURNEY OF DREAMS! MUSIKLADEN CONCERT 1981 ‘Low rock’ legends MORPHINE lead the MVD charge in October with the quintessential DVD documentary of the band JOURNEY OF DREAMS. Witness numbing live performances and see and hear the story of the iconic group, told by surviving members and notable fans like Henry Rollins and Joe Strummer. JOURNEY OF DREAMS tracks Morphine’s meteoric rise from club band to international icons. Getting progressively better with age are VAN DER GRAAF GENERATOR with their brand new album DO NOT DISTURB, available on CD and limited edition 180 gram vinyl! Ethereal and excellent! Legendary theatrical rock band THE TUBES get their due on DVD and CD in October with LIVE AT GERMAN TELEVISION: THE MUSIKLADEN CONCERT 1981. Taped at the band’s zenith, this release features the album THE COMPLETION BACKWARDS PRINCIPLE, featuring the hits “Talk to Ya Later” and “Don’t Want to Wait Anymore.” Re-connect with the organic adventures of Fred and Carrie with the latest installment of the comedy series PORTLANDIA! Season 6 features guest stars Danzig, The Flaming Lips, Louis C.K. -

Pacnwtechno-Minty-Tv

NOTES FROM THE UNDERGROUND NOTES FROM THE UNDERGROUND From Industrial to Techno: Industrial Isolation Trackin' Techno the Secret History of Pacific Northwest Techno by tobias c. van Veen The path to fame in Vancouver is weird, but normal It was in the same mid-‘90s era that Vancouver's for the recognition of a sound. The industrial scene techno underground was forming. In Victoria, artists had the most influence outside its coastal home... who are recognized today on Spencer's itiswhatitis I imagined it all... secret underground cults of Pacific Re-mixing the strategy and not to be dismayed, I but this boomerang returned, for Algorithm and label were DJing and collecting gear and setting Northwest techno DJs, worshipping Detroit in dark turned to CiTR's DJ Noah. Tyler remembers him well other debtors to the industrial world, such as Richie forth their first productions — Matt Johnson, Tyger warehouses far from the grind of the househeads... as a DJ who "played more techno than most." I used Hawtin, had a longstanding influence on the gener- Dhula, Cobblestone Jazz and Colin the Mole. and then I was snapped out of the dream. to tune into Noah's Homebass show on Friday ation of DJs that came after Tyler Stadius. But this Vancouver witnessed the appearance of Loscil, Ben nights — which is still running — and it influenced was evidently still a few years to come and on the Nevile, Kerry Uchida and Steb Sly. A primary force at me for years. As Tyler says, "Noah played what fringe of Vancouver's music history.