Illinois Classical Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

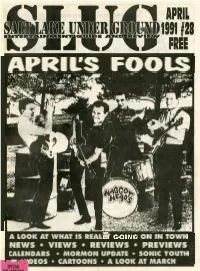

April's Fools

APRIL'S FOOLS ' A LOOK AT WHAT IS REAL f ( i ON IN. TOWN NEWS VIEWS . REVIEWS PREVIEWS CALENDARS MORMON UPDATE SONIC YOUTH -"'DEOS CARTOONS A LOOK AT MARCH frlday, april5 $7 NOMEANSNO, vlcnms FAMILYI POWERSLAVI saturday, april 6 $5 an 1 1 piece ska bcnd from cdlfomb SPECKS witb SWlM HERSCHEL SWIM & sunday,aprll7 $5 from washln on d.c. m JAWBO%, THE STENCH wednesday, aprl10 KRWTOR, BLITZPEER, MMGOTH tMets $10raunch, hemmetal shoD I SUNDAY. APRIL 7 I INgTtD, REALITY, S- saturday. aprll $5 -1 - from bs aqdes, califomla HARUM SCAIUM, MAG&EADS,;~ monday. aprlll5 free 4-8. MAtERldl ISSUE, IDAHO SYNDROME wedn apri 17 $5 DO^ MEAN MAYBE, SPOT fiday. am 19 $4 STILL UFEI ALCOHOL DEATH saturday, april20 $4 SHADOWPLAY gooah TBA mday, 26 Ih. rlrdwuhr tour from a land N~AWDEATH, ~O~LESH;NOCTURNUS tickets $10 heavy metal shop, raunch MATERIAL ISSUE I -PRIL 15 I comina in mayP8 TFL, TREE PEOPLE, SLaM SUZANNE, ALL, UFT INSANE WARLOCK PINCHERS, MORE MONDAY, APRIL 29 I DEAR DICKHEADS k My fellow Americans, though:~eopledo jump around and just as innowtiwe, do your thing let and CLIJG ~~t of a to NW slam like they're at a punk show. otherf do theirs, you sounded almost as ENTEIWAINMENT man for hispoeitivereviewof SWIM Unfortunately in Utah, people seem kd as L.L. "Cwl Guy" Smith. If you. GUIIBE ANIB HERSCHELSWIMsdebutecassette. to think that if the music is fast, you are that serious, I imagine we will see I'mnotamemberofthebancljustan have to slam, but we're doing our you and your clan at The Specks on IMVIEW avid ska fan, and it's nice to know best to teach the kids to skank cor- Sahcr+nightgiwingskrmkin'Jessom. -

Their Lived Experience in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit Andrea Prentiss Baptist Hospital of Miami, [email protected]

Baptist Health South Florida Scholarly Commons @ Baptist Health South Florida All Publications 2014 Hearing the Child's Voice: Their Lived Experience in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit Andrea Prentiss Baptist Hospital of Miami, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.baptisthealth.net/se-all-publications Part of the Critical Care Nursing Commons, Maternal, Child Health and Neonatal Nursing Commons, and the Pediatrics Commons Citation Prentiss, Andrea, "Hearing the Child's Voice: Their Lived Experience in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit" (2014). All Publications. 649. https://scholarlycommons.baptisthealth.net/se-all-publications/649 This Article -- Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons @ Baptist Health South Florida. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons @ Baptist Health South Florida. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida HEARING THE CHILD’S VOICE: THEIR LIVED EXPERIENCE IN THE PEDIATRIC INTENSIVE CARE UNIT A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in NURSING by Andrea S. Prentiss 2014 To: Dean Ora Lea Strickland Nicole Wertheim College of Nursing & Health Sciences This dissertation, written by Andrea S. Prentiss entitled Hearing the Child’s Voice: Their Lived Experience in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this dissertation and recommend that it be approved. _______________________________________ Dionne Stephens _______________________________________ Jean Hannan _______________________________________ Dorothy Brooten _______________________________________ JoAnne Youngblut, Major Professor Date of Defense: November 12, 2014 The dissertation of Andrea S. -

2011-11-25 1. När Det Är Spelning På Nuclear Nation Brukar Det Komma

Nuclear Nation Quiz - 2011-11-25 1. När det är spelning på Nuclear Nation brukar det komma mycket folk. Det gör det ibland även annars och då kan det bli långa köer som ringlar sig runt Linköping. Under tidigt 2000-tal kunde NN- besökare vid ett festtillfälle slippa kötristeseen och gå direkt in på festen förutsatt att de uppfyllde ett krav. Vad skulle två NN-besökare göra för att få gå före i kön? A: Bära likadana kläder B: Kunna texten till Headhunter utantill och sjunga den tvåstämmigt C: Vara fastkedjade i varandra 2. Ni befinner er just nu på synthquiz med den anrika synthföreningen Nuclear Nation, men det var inte helt självklart att vi skulle heta just så. Vilket annat namn fanns som förslag? A: Eclipse B: Solaris C: SUN 3. Apoptygma Berzerk gjorde 98 en spelning i Leipzig från vilken i alla fall en liten del kom med på skivan APBL98. Trots att bandet körde på som hårdast med en Depeche-cover som folk verkade uppskatta, så fick spelningen ett snöpligt slut. Men vad hände? A: Det utbröt en mindre en brand i ljudteknikerbåset pga. underdimensionerade elkablar. B: Spelningen råkade äga rum samma kväll som kraftverket Holzkohle fallerade, vilket ledde till Leipzigs hittills största elavbrott. C: Trots att Apoptygma ville köra en låt till, så stängde polisen ner konserten i förtid. 4. En inställd spelning är också en spelning brukar man säga och ett band som skulle ha spelat på NN för ett antal år sedan, men som tyvärr fick ställa in p.g.a. sjukdom var... ja, vilket band då? A: Covenant B: VNV Nation C: Tyskarna från Lund 5: Ett band som dock har spelat på NN är LOWE. -

Renaissance Receptions of Ovid's Tristia Dissertation

RENAISSANCE RECEPTIONS OF OVID’S TRISTIA DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Gabriel Fuchs, M.A. Graduate Program in Greek and Latin The Ohio State University 2013 Dissertation Committee: Frank T. Coulson, Advisor Benjamin Acosta-Hughes Tom Hawkins Copyright by Gabriel Fuchs 2013 ABSTRACT This study examines two facets of the reception of Ovid’s Tristia in the 16th century: its commentary tradition and its adaptation by Latin poets. It lays the groundwork for a more comprehensive study of the Renaissance reception of the Tristia by providing a scholarly platform where there was none before (particularly with regard to the unedited, unpublished commentary tradition), and offers literary case studies of poetic postscripts to Ovid’s Tristia in order to explore the wider impact of Ovid’s exilic imaginary in 16th-century Europe. After a brief introduction, the second chapter introduces the three major commentaries on the Tristia printed in the Renaissance: those of Bartolomaeus Merula (published 1499, Venice), Veit Amerbach (1549, Basel), and Hecules Ciofanus (1581, Antwerp) and analyzes their various contexts, styles, and approaches to the text. The third chapter shows the commentators at work, presenting a more focused look at how these commentators apply their differing methods to the same selection of the Tristia, namely Book 2. These two chapters combine to demonstrate how commentary on the Tristia developed over the course of the 16th century: it begins from an encyclopedic approach, becomes focused on rhetoric, and is later aimed at textual criticism, presenting a trajectory that ii becomes increasingly focused and philological. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedtbrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. University Microfilms international A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 N orth Z eeb Roaci Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313 761-4700 800-521-0600 Order Number 9505378 A schema for the construction and assessment of messages of emp owerment Ranney, Arthur Lytle, Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1994 UMI 300 N. -

Black Monday Magazine

5333 north lincoln avenue #3n chicago illinois 60625 black mon day START v1.4 day mon black :::BLACK MONDAY V1.4::: controlled bleeding noise unit advertise (it’s very affordable!) windsdieddownadifferen controlled bleedingnoiseunitadvertise (it’s advertise (it’s very affordable!) windsdieddownadifferent advertise kindofcopthetablesecular (it’s my lifewiththethrillkillkult sistermachinegunslaveunitkraftwelt beautyw acumen alienfaktor battery collide controlledbleedingnoiseunitadvert noise unit advertise (it’s very affordable!) windsdieddownadifferent noise unitadvertise kindofcoptheta (it’s able!) vault.9rosettastoneseveredheadstherazorskylinegrotuskmfdm grotusdown kmfdm a different kind my of verylife affordable!) mechanism insight23 christanaloguevampirerodentsadvertise (it’s cop with the thrill the kill table kult secularsister machine mechanism gun insightslave unit23 kraftchristwelt analogu e beauty vampire wired rodents under advertise the noise (it’s very affordable!) advertise (it’s very vault.9 affordable!) rosetta stone16 volt christ analogue vampire rodents advertise (it’s very affordable!) vault.9rosetta stone christ analoguevampirerodentsadvertise (it’s kraftwelt beauty wired under the noise advertise (it’s very affordable!) 16volt kraftwelt beautywiredunderthenoiseadvertise (it’s slave unit kraftwelt beauty wired under the noise advertise (it’s very affordable! slave unitkraftweltbeautywired under thenoiseadvertise (it’s pire rodents advertise (it’s very affordable!) vault.9rosettastoneseveredheads pire rodentsadvertise -

Environmental Impact Assessment

SFG1219 v3 World Bank-financed Integrated Economic Development of Small Towns Project (IEDSTP)in Xiantang Town Dongyuan County,Heyuan City Environmental Impact Assessment Xiantang town Government in Dongyuan County Guangzhou Research Institute of Environment Protection June 2015 - 1 - Abbreviations and Acronyms CSEE Construction Supervision Environmental Engineer CDD Community Driven Development DI Design Institute EA Environmental Assessment EIA Environmental Impact Assessment EMP Environmental Management Plan EMS Environmental Monitoring Station EPB Environmental Protection Bureau EMC Enviornmental Management Coordinator IA Implementation Agency MEP Ministry of Environmental Protection PO Project Owner PMO Project Management Office PRC The People's Republic ofChina SE Supervision Engineer TOR Terms of Reference WB World Bank XIEDTSP World Bank-funded Xiantang Integrated Economic Development of Small Towns Project CURRENCIES & OTIIER UNITS MU Area Unit (JMU=O.0667hm2) RMB Chinese Yuan (Renminbi) USD United States Dollar Exchange rate 1 USD=6.78 RMB CHEMICAL ABBREVIATIONS BOD5 Biochemical Oxygen Demand (5 days) COD Chemical Oxygen Demand CODMn Permanganate Index NH3-N Ammonia Nitrogen SS Suspended Solids TN Total Nitrogen TP Total Phosphorus TSP Total Suspended Particulates TSS Total Suspended Solids Leq Equivalent Continuous Noise Level - 2 - Contents 1 General ................................................................................................................................ - 1 - 1.1 Project Overview ..................................................................................................... -

High-Speed Ground Transportation Noise and Vibration Impact Assessment

High-Speed Ground Transportation U.S. Department of Noise and Vibration Impact Assessment Transportation Federal Railroad Administration Office of Railroad Policy and Development Washington, DC 20590 Final Report DOT/FRA/ORD-12/15 September 2012 NOTICE This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Government assumes no liability for its contents or use thereof. Any opinions, findings and conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the United States Government, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the United States Government. The United States Government assumes no liability for the content or use of the material contained in this document. NOTICE The United States Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. Trade or manufacturers’ names appear herein solely because they are considered essential to the objective of this report. REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188), Washington, DC 20503. -

Muzikološki Z B O R N I K L

MUZIKOLOŠKI ZBORNIK MUSICOLOGICAL ANNUAL L / 2 ZVEZEK/VOLUME L J U B L J A N A 2 0 1 4 Glasba kot sredstvo in predmet v procesih sakralizacije profanega in profanacije sakralnega Sacralization of the Profane and Profanation of the Sacred: Music as a Means and an Object Izdaja • Published by Oddelek za muzikologijo Filozofske fakultete Univerze v Ljubljani Urednik zvezka • Edited by Aleš Nagode (Ljubljana) Glavni in odgovorni urednik • Editor-in-chief Jernej Weiss (Ljubljana) Asistentka uredništva • Assistant Editor Tjaša Ribizel (Ljubljana) Uredniški odbor • Editorial Board Matjaž Barbo (Ljubljana) Aleš Nagode (Ljubljana) Svanibor Pettan (Ljubljana) Leon Stefanija (Ljubljana) Andrej Rijavec (Ljubljana), častni urednik • honorary editor Mednarodni uredniški svet • International Advisory Board Michael Beckermann (Columbia University, USA) Nikša Gligo (University of Zagreb, Croatia) Robert S. Hatten (Indiana University, USA) David Hiley (University of Regensburg, Germany) Thomas Hochradner (Mozarteum Salzburg, Austria) Bruno Nettl (University of Illinois, USA) Helmut Loos (University of Leipzig, Germany) Jim Samson (Royal Holloway University of London, UK) Lubomír Spurný (Masaryk University Brno, Czech Republic) Katarina Tomašević (Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Serbia) John Tyrrell (Cardiff University, UK) Michael Walter (University of Graz, Austria) Uredništvo • Editorial Address Oddelek za muzikologijo Filozofska fakulteta Aškerčeva 2, SI-1000 Ljubljana, Slovenija e-mail: [email protected] http://revije.ff.uni-lj.si/MuzikoloskiZbornik Cena posamezne številke • Single issue price 10 EUR Letna naročnina • Annual subscription 20 EUR Založila • Published by Znanstvena založba Filozofske fakultete Univerze v Ljubljani Za založbo • For the publisher Branka Kalenić Ramšak, dekanja Filozofske fakultete Tisk • Printed by Birografika Bori d.o.o., Ljubljana Naklada 500 izvodov • Printed in 500 copies Rokopise, publikacije za recenzije, korespondenco in naročila pošljite na naslov izdajatelja. -

Aesthetics, the Body, and Erotic Literature in the Age of Lessing

HEAVING AND SWELLING: AESTHETICS, THE BODY, AND EROTIC LITERATURE IN THE AGE OF LESSING Derrick Ray Miller A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Germanic Languages and Literatures. Chapel Hill 2007 approved by: Eric Downing Jonathan Hess (advisor) Clayton Koelb Alice Kuzniar Richard Langston © 2007 Derrick Ray Miller ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT DERRICK RAY MILLER: Heaving and Swelling: Aesthetics, the Body, and Erotic Literature in the Age of Lessing (Under the direction of Jonathan Hess) In this dissertation, I explore how signs affect the body in German neoclassicism. This period constructs a particular body (the voluptuary’s body) that derives primarily sensual—as opposed to cognitive—pleasure from the signs of art. Erotic literature with its sensual appeal, then, becomes a special case of art, one that manifests this relationship between signs and the body the most clearly. By focusing on erotic literature as a paradigmatic rather than a marginal case of literature, I am able to reconsider our current understanding of German neoclassicism. Erotic literature exceeds the aesthetic and semiotic principles that scholars have come to expect to circumscribe the literature of this period. Erotic literature moves beyond such categories as vividness, veracity, and verisimilitude to achieve an aesthetic pleasure of virtuality. Its arousing signs produce voluptuous sensations and transformations in the reader’s body in addition to transmitting knowledge and manipulating affect. And as they strike—or stroke—the body, these signs appear less transparent than sticky. -

228 Notes to Page 3 Representation: Kathryn Gravdal, Ravishing

228 Notes to page 3 representation: Kathryn Gravdal, Ravishing Maidens: Writing Rape in Medieval French Literature and Law (Philadelphia: University of Penn- sylvania Press, 1991); Karen Greenberg, ``Reading Reading: Echo's Abduc- tion of Language'' in Women and Language in Literature and Society, ed. Sally McConnell-Ginet, Ruth Borker, and Nelly Furman (New York: Praeger, 1980); Mary Jacobus, ``Freud's Mnemonic: Women, Screen Mem- ories, and Feminist Nostalgia,'' Michigan Quarterly Review 26 (Winter 1987): 117±139; Ann Rosalind Jones, ``New Songs for the Swallow: Ovid's Philomela in Tullia d'Aragona and Gaspara Stampa,'' in Re®guring Woman: Perspectives on Gender and the Italian Renaissance, eds. Juliana Schiesari and Marilyn Migiel (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1991) and ``Demater- ializations: Textile and Textual Properties in Ovid, Sandys, and Spenser'' in Subject and Object in Renaissance Culture, ed. Margreta de Grazia, Maureen Quilligan and Peter Stallybrass (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), pp. 189±212; Patricia Klindienst Joplin, ``The Voice of the Shuttle is Ours,'' Stanford Literature Review 1, 1 (Spring 1984): 25±53; Amy Lawrence, Echo and Narcissus: Women's Voices in Classical Hollywood Cinema (Berk- eley: University of California Press, 1991); Elissa Marder, ``Disarticulated Voices: Feminism and Philomela,'' Hypatia: A Journal of Feminist Phil- osophy, 7, 2 (Spring 1992): 148±66; Nancy K. Miller, ``Arachnologies: The Woman, the Text, and the Critic,'' in The Poetics of Gender, ed. Nancy K. Miller (New York: Columbia University Press, 1986); Tanya Modleski, ``Feminism and the Power of Interpretation: Some Critical Readings,'' in Feminist Studies/Critical Studies, ed. Teresa De Lauretis (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1986); Claire Nouvet, ``An Impossible Response: the Disaster of Narcissus,'' Yale French Studies 79 (1991): 95±109; Amy Richlin, ``Reading Ovid's Rapes,'' in Pornography and Representation in Greece and Rome, ed. -

107 V Ariations on the Unexpected

107 Variations on the Unexpected SURPRISE 107 Variations on the Unexpected Dedication and Prelude To Raine Daston In his essay “Of Travel,” Francis Bacon recommends that diaries be used to register the things “to be seen and observed.” Upon returning home, the traveler should not entirely leave the visited countries, but maintain a correspondence with those she met, and let her experi- ence appear in discourse rather than in “apparel or gesture.” Your itineraries through a vast expanse of the globe of knowledge seem to illustrate Bacon’s recommendations, and have inspired many to em- bark on the exploration of other regions—some adjacent, some dis- tant from the ones you began to clear. Yet not all have journeyed as well equipped as you with notebooks, nor assembled them into a trove apt to become, as Bacon put it, “a good key” to inquiry. As you begin new travels, you may add the present collection to yours, and adopt the individual booklets as amicable companions on the plane or the U-Bahn. Upon wishing you, on behalf of all its contributors, Gute Reise! and Bon voyage!, let us tell you something about its gen- esis and intention. Science depends on the unexpected. Yet surprise and its role in the process of scientific knowledge-making has hitherto received lit- tle attention, let alone systematic investigation. If such a study ex- isted, it would no doubt have been produced in your Department at the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science. The topic is a seamless match with your interest in examining ideals and practices of scientific and cultural rationality—ideals and practices often so fundamental that they appear to transcend history or are overlooked altogether.