107 V Ariations on the Unexpected

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gay Marriage Opponents Closer To

Columbia Foundation Articles and Reports July 2012 Arts and Culture ALONZO KING’S LINES BALLET $40,000 awarded in August 2010 for two new world-premiere ballets, a collaboration with architect Christopher Haas (Triangle of the Squinches) and a new work set to Sephardic music (Resin) 1. Isadora Duncan Dance Awards, March 27, 2012 2012 Isadora Duncan Dance Award Winners Announced Christopher Haas wins a 2012 Isadora Duncan Dance Award for Outstanding Achievement in Visual Design for his set design for Triangle of the Squinches. Alonzo King’s LINES Ballet wins two other Isadora Duncan Dance Awards for the production Sheherazade. ASIAN ART MUSEUM $255,000 awarded since 2003, including $50,000 in July 2011 for Phantoms of Asia, the first major exhibition of Asian contemporary art from May 18 to September 2, 2012, which explores the question “What is Asia?” through the lens of supernatural, non-material, and spiritual sensibilities in art of the Asian region 2. San Francisco Chronicle, May 13, 2012 Asian Art Museum's 'Phantoms of Asia' connects Phantoms of Asia features over 60 pieces of contemporary art playing off and connecting with the Asian Art Museum's prized historical objects. According to the writer, Phantoms of Asia, the museum’s first large-scale exhibition of contemporary art is an “an expansive and ambitious show.” Allison Harding, the Asian Art Museum's assistant curator of contemporary art says, “We're trying to create a dialogue between art of the past and art of the present, and look at the way in which artists today are exploring many of the same concerns of artists throughout time. -

Muzikološki Z B O R N I K L

MUZIKOLOŠKI ZBORNIK MUSICOLOGICAL ANNUAL L / 2 ZVEZEK/VOLUME L J U B L J A N A 2 0 1 4 Glasba kot sredstvo in predmet v procesih sakralizacije profanega in profanacije sakralnega Sacralization of the Profane and Profanation of the Sacred: Music as a Means and an Object Izdaja • Published by Oddelek za muzikologijo Filozofske fakultete Univerze v Ljubljani Urednik zvezka • Edited by Aleš Nagode (Ljubljana) Glavni in odgovorni urednik • Editor-in-chief Jernej Weiss (Ljubljana) Asistentka uredništva • Assistant Editor Tjaša Ribizel (Ljubljana) Uredniški odbor • Editorial Board Matjaž Barbo (Ljubljana) Aleš Nagode (Ljubljana) Svanibor Pettan (Ljubljana) Leon Stefanija (Ljubljana) Andrej Rijavec (Ljubljana), častni urednik • honorary editor Mednarodni uredniški svet • International Advisory Board Michael Beckermann (Columbia University, USA) Nikša Gligo (University of Zagreb, Croatia) Robert S. Hatten (Indiana University, USA) David Hiley (University of Regensburg, Germany) Thomas Hochradner (Mozarteum Salzburg, Austria) Bruno Nettl (University of Illinois, USA) Helmut Loos (University of Leipzig, Germany) Jim Samson (Royal Holloway University of London, UK) Lubomír Spurný (Masaryk University Brno, Czech Republic) Katarina Tomašević (Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Serbia) John Tyrrell (Cardiff University, UK) Michael Walter (University of Graz, Austria) Uredništvo • Editorial Address Oddelek za muzikologijo Filozofska fakulteta Aškerčeva 2, SI-1000 Ljubljana, Slovenija e-mail: [email protected] http://revije.ff.uni-lj.si/MuzikoloskiZbornik Cena posamezne številke • Single issue price 10 EUR Letna naročnina • Annual subscription 20 EUR Založila • Published by Znanstvena založba Filozofske fakultete Univerze v Ljubljani Za založbo • For the publisher Branka Kalenić Ramšak, dekanja Filozofske fakultete Tisk • Printed by Birografika Bori d.o.o., Ljubljana Naklada 500 izvodov • Printed in 500 copies Rokopise, publikacije za recenzije, korespondenco in naročila pošljite na naslov izdajatelja. -

Aesthetics, the Body, and Erotic Literature in the Age of Lessing

HEAVING AND SWELLING: AESTHETICS, THE BODY, AND EROTIC LITERATURE IN THE AGE OF LESSING Derrick Ray Miller A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Germanic Languages and Literatures. Chapel Hill 2007 approved by: Eric Downing Jonathan Hess (advisor) Clayton Koelb Alice Kuzniar Richard Langston © 2007 Derrick Ray Miller ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT DERRICK RAY MILLER: Heaving and Swelling: Aesthetics, the Body, and Erotic Literature in the Age of Lessing (Under the direction of Jonathan Hess) In this dissertation, I explore how signs affect the body in German neoclassicism. This period constructs a particular body (the voluptuary’s body) that derives primarily sensual—as opposed to cognitive—pleasure from the signs of art. Erotic literature with its sensual appeal, then, becomes a special case of art, one that manifests this relationship between signs and the body the most clearly. By focusing on erotic literature as a paradigmatic rather than a marginal case of literature, I am able to reconsider our current understanding of German neoclassicism. Erotic literature exceeds the aesthetic and semiotic principles that scholars have come to expect to circumscribe the literature of this period. Erotic literature moves beyond such categories as vividness, veracity, and verisimilitude to achieve an aesthetic pleasure of virtuality. Its arousing signs produce voluptuous sensations and transformations in the reader’s body in addition to transmitting knowledge and manipulating affect. And as they strike—or stroke—the body, these signs appear less transparent than sticky. -

Memory in Search of History and Democracy Editor’S Letter by June Carolyn Erlick

fall 2013 harvard review of latin america memory in search of history and democracy editor’s letter by june carolyn erlick The Past Is Present Irma Flaquer’s image as a 22-year-old Guatemalan reporter stares from the pages of a 1960 harvard review of latin america Time magazine, her eyes blackened by a government mob that didn’t like her feisty stance. fall 2013 She never gave up, fighting with her pen against the long dictatorship, suffering a car bomb Volume Xiii no. 1 explosion in 1970, then being dragged by her hair from her car one October ten years later and disappearing. Published by the david Rockefeller Center I knew she was courageous. I became intrigued by her relentless determination—why did for Latin American Studies she keep on writing? However, the case was already old even in 1996, when the Inter Ameri- Harvard university volume Xiii no. 1 can Press Association (IAPA) assigned me the investigation for its new Impunity Project. Irma David Rockefeller Center was one of Guatemala’s 45,000 disappeared—one of thousands in Latin America, men and for Latin American Studies women forcibly vanished, mostly killed. Yet I learned from the investigation that disappear- director ance is a crime against humanity, a crime not subject to a statute of limitations. Merilee S. Grindle memory And I also learned from Irma’s courageous sister Anabella that it really is a crime that executive director in eVery issue never ends. “They took my moral support, my counselor; in killing my sister, they stole my Kathy Eckroad human right,” Anabella told IAPA members at a Los Angeles meeting. -

Front Line Assembly - Bio

FRONT LINE ASSEMBLY - BIO Front Line Assembly is the primary focus of Vancouver-based musician Bill Leeb. A founding member of Skinny Puppy, Leeb moved on to form FLA in 1986 with Michael Balch, releasing some cassettes (since released as Total Terror I & II) which paved the way for their 1987 releases: The Initial Command, State of Mind, and Corrosion. In late 1988, they recorded the mini-LP Disorder, since combined with Corrosion and released as Corroded Disorder. Their 1989 release, Gashed Senses and Crossfire, further cemented their popularity in the industrial scene, and prompted their first world tour. By 1990, Balch had departed and Rhys Fulber rounded out the duo, releasing Caustic Grip. But it was two years later when the duo released the classic album, Tactical Neural Implant, which has become for many, the genre's crowning moment. To this day, TNI still defines the best of industrial music. FLA enraged many of their fans in 1994 when they began to experiment with their established electronic-only sound. Millenium, with its heavy doses of live and sampled metal guitars, dared its audience to grow and expand with the band beyond industrial's perceived barriers. Front Line stepped to the firing line again in 1995 with Hard Wired, which reflected both a return to form and a continued embracing of the guitar. Hard Wired not only picked up where Implant left off, it improved on the sound by adding in elements of all of their side projects. A fall European tour was recorded for the 1996 release Live Wired, their first concert CD ever. -

LOGOS Mankind 13 Ment 14» UPHOLDING the PURITY of the APOSTOLIC DOCTRINE Christ Expected 14 the Significance of the London and FAITH

1OGOS cf) of Coc/<snc/ /<eep // INDEX TO VOLUME TWELVE A MONTHLY PUBLICATION DEVOTED TO THE PROPAGATION OF PROVED BIBLICAL TRUTHS ENUMERATED IN THE WORKS OF DR. THOMAS AND ROBERT ROBERTS. WISDOM IS THE PRINCIPAL THING; THEREFORE GET WISDOM. 1ΉΕ ORGAN OF THE CHRISTADELPHIAN "ELPIS ISRAEL" CLASSES OF AUSTRALIA. Edited \>y H. P. Mansfield. Subscription: Five Shillings per annum. All Co/nniunications to be forwarded to the Editor. 62 Denman Terrace, Mitcham Estate, S.A. i t (Registered at the G.P.O., Melbourne, for transmission by post as a Periodical). Name of the Lord is a strong tower; the righteous info it and are safe." The Cliristadelphian Treasury Christ's Return in Relation to Too Much Denunciation . Armageddon 50 Dr. Thomas's Last Will and Testament . Dr. Thomas Notable Events 50 and his Work ..... Dr. The Arabs 52 Thomas Repudiates Auth- TJie Close of 1945 74 ority ... Bro. Roberts fol- Brethren Watch and Work .. 75 lows - Dr. Thomas 20 Egypt 78 Paul #nc} Dr. Thomas . I have taken away Peace from 1 Quasi Ohristadelphiahs . this People .. .... ..% 108 General Articles Jjie Mormng Sia? , ^4 vi Christ's meaning of Reviling Voices from the Past Types andgfeStow^ of thwe ^w 2X7 . .* . Ho Christadelphian 130, 154, 178, 204, 226 Qod i$ our Refuge and ™* Ht«%rarf .^.r . .'-*? ^| Truce . \'.' . driticising Dr. 5 Wisdom in the Scriptures .. 2^2 Jfiomas .. .... .. .... 67 Points from the Press ^ Ecclesia at Sardis .... 7 Adam and Mortality 237 , 130, 155, 179, 227 Hobert Roberts on Dr. Thomas Land Laws 9 The t«aw of Moses .. .. .... 241: The London Conference . -

The Social Brain

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Social and Cultural Sciences Faculty Research and Social and Cultural Sciences, Department of Publications 1-1-2017 The oS cial Brain Alexandra Crampton Marquette University, [email protected] Published version. "The ocS ial Brain." in The Negotiator's Desk Reference / Christopher Honeyman, Andrea Kupfer Schneider, editors. Saint Paul, Minn. : DRI Press, [2017]: 115-125. Publisher link. © 2017 DRI Press. Used with permission. The Social Brain Alexandra Crampton Editors' Ni huma b ?te: The economists' traditional and convenient concept of been ti emgs as rational actors who pursue self-interest has by now factor. 0:ough[y amended, if not debunked. But how the complicating actuaz1' mclud!ng gender, culture, emotion, and cognitive distortions, ho,,. Y UJork m our brains has been elusive until more recently. Lately, wever ne . d b und ' urosczence has begun to make znroads towar a etter larg!rs!anding of many of these factors. This chapter describes one ofah f~re ?fthe puzzle: the evolution ofhuman beings' brains as those . lg Y znterdependent, social species. Introduction :N egotiato ft Who rs O en presume that the best negotiators are rational actors and c~n accurately assess a given situation, identify all possible options, We r:e 1ct the best options. As previous scholarship has shown, however, cogn 1.tr~ Ynegotiate in such a simple and straightforward way-emotions, that comIve distort·. ions, gender, and culture are among t h e many .c1actors come rJhcate both how we negotiate and the range of potential out may bs. d ore recently, neuroscience has offered insight into how this depen~ ue to t~e evolution of our brains. -

Illinois Classical Studies

UMVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN CLASSICS The person charging this material is re- sponsible for its return to the library from which it was withdrawn on or before the Latest Date stamped below. Theft, mutilation, and underlining of books are reasons for disciplinary action and may result in dismissal from the University. To renew call Telephone Center, 333-8400 UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN JUL i G !S:ig OCT 1 1 ?(05 L161—O-1096 L<(TL--VJA-<.\J^ ILLINOIS CLASSICAL STUDIES VOLUME IX. 1 SPRING 1984 J. K. Newman, Editor ISSN 0363-1923 1 1 ILLINOIS CLASSICAL STUDIES VOLUME IX. Spring 1 984 J. K. Newman, Editor Patet omnibus Veritas; nondum est occupata; multum ex ilia etiam futuris relictum est. Sen. Epp. 33. 1 SCHOLARS PRESS ^^-^ ISSN 0363-1923 ^9^^ 1 ILLINOIS CLASSICAL STUDIES VOLUME IX. ©1984 Scholars Press 101 Salem Street P.O. Box 2268 Chico, California 95927 Printed in the U.S.A. ADVISORY EDITORIAL COMMITTEE John J. Bateman Howard Jacobson Harold C. GotofF David Sansone Responsible Editor: J. K. Newman The Editor welcomes contributions, which should not normally exceed twenty double-spaced typed pages, on any topic relevant to the elucidation of classical antiquity, its transmission or influence. Con- sistent with the maintenance of scholarly rigor, contributions are especially appropriate which deal with major questions of interpre- tation, or which are likely to interest a wider academic audience. Care should be taken in presentation to avoid technical jargon, and the trans-rational use of acronyms. Homines cum hominibus loquimur. Contributions should be addressed to: The Editor, Illinois Classical Studies, Department of the Classics, 4072 Foreign Languages Building, 707 South Mathews Avenue, Urbana, Illinois 61801 Each contributor receives twenty-five offprints. -

1 Inhalt 1 5 New.Indd

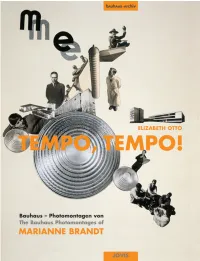

TEMPO, TEMPO! jovis Elizabeth Otto TEMPO, TEMPO! Bauhaus -Photomontagen von The Bauhaus Photomontages of MARIANNE BRANDT jovis Dieses Buch erscheint anlässlich der Ausstellung: This book coincides with the exhibition: „Tempo, Tempo! Bauhaus-Photomontagen von Marianne Brandt“ Bauhaus-Archiv, Berlin: 12.10.2005 – 9. 01.2006 Busch-Reisinger Museum, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass.: 11.03. – 21. 05.2006 International Center of Photography, New York: 9.06. – 27.08.2006 Kunstsammlungen Chemnitz Unser besonderer Dank gilt den Leihgebern, die zum Gelingen dieser Ausstellung beigetragen haben: Galerie Berinson, Berlin/ UBU Gallery, New York Galerie Kicken, Berlin Stiftung Bauhaus Dessau Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden Militärhistorisches Museum der Bundeswehr Dresden Bernd Freese, Frankfurt/Main Sammlung Gisela und Hans-Peter Schulz, Leipzig National Gallery of Art, Washington Klassik Stiftung Weimar Privatsammlung, über Galerie Ulrich Fiedler, Köln Konzeption von Ausstellung und Katalog Exhibition and catalogue concept: Elizabeth Otto Übersetzung Englisch-Deutsch Translation English-German: Stephanie Rupp, Berlin Übersetzung Deutsch-Englisch (falls nicht anders vermerkt) Translation German-Englisch (unless otherwise noted): Elizabeth Otto Gestaltung Design and Layout: Sven Schrape, Katrin Wenke, Susanne Rösler Satz Typesetting: Daniela Rust Lithographie Lithography: Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin, Galrev Druck- und Verlagsgesellschaft, Berlin Digitale Bildbearbeitung Digital Image Editing: Arno Dettmers, Markus Hawlik, Norbert -

Front Line Assembly Circuitry Mp3, Flac, Wma

Front Line Assembly Circuitry mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic Album: Circuitry Country: US Released: 1995 Style: Industrial MP3 version RAR size: 1897 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1333 mb WMA version RAR size: 1419 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 587 Other Formats: DMF TTA VQF MOD MIDI AU AHX Tracklist Hide Credits 1 Circuitry (Predator Mix) 7:23 Circuitry (Biosphere Remix) 2 6:35 Remix – BiosphereRemix [Credited To] – Geir Jenssen 3 Epidemic 5:35 Circuitry (Complexity Remix By Haujobb) 4 7:18 Remix – Haujobb Companies, etc. Licensed From – Westcom GmbH Copyright (c) – Metropolis Records Published By – Warner/Chappell Designed At – Hourglass Glass Mastered At – Nimbus Credits Engineer [Assistant] – Delwyn Brooks Guitar – Devin Townsend Mixed By, Engineer – Greg Reely Performer [Electronic Execution], Written By – Bill Leeb, Rhys Fulber Notes Artwork at Hourglass Printed in Canada. Multimedia part contains "Millennium" video, discography, sound, and pictures. © 1995 Metropolis Records Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode (Text): 7 82388 0014 2 7 Matrix / Runout: MET014 Mastering SID Code: IFPI L125 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year SPV 055-22303 SPV 055-22303 CDS, SPV Front Line Circuitry (CD, Off Beat, Off CDS, SPV Germany 1995 055-22303, CDS Assembly Single, Enh) Beat, Off Beat 055-22303, CDS 055-22303 055-22303 Front Line Circuitry (4xFile, none Metropolis none US 2009 Assembly AAC, EP, RE, 128) Front Line Circuitry (12", Artoffact AOF196 AOF196 Canada 2015 Assembly Ltd, RE, Yel) -

Reading, Travel, and the Pedagogy of Growing up in Late Nineteenth-Century Germany M

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) Spring 4-23-2013 Reading, Travel, and the Pedagogy of Growing Up in Late Nineteenth-Century Germany M. Stanley Majors Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd Part of the German Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Majors, M. Stanley, "Reading, Travel, and the Pedagogy of Growing Up in Late Nineteenth-Century Germany" (2013). All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs). 1090. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd/1090 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS Department of Germanic Languages and Literatures Dissertation Examination Committee: Lynne Tatlock, Chair Miriam Bailin Matt Erlin Lutz Koepnick Paul Michael Luetzeler William McKelvy Reading, Travel, and the Pedagogy of Growing Up in Late Nineteenth-Century Germany by Magdalen Stanley Majors A dissertation presented to the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2013 St. Louis, Missouri © 2013, Magdalen Stanley Majors TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS…………………………...………………………...………...……iii -

The Brain, Body, Emotional Connection Webinar

Brain, Body, Emotion Connection Roseann Bayne 1 Mexico Brain, Body, Emotion 2020 Roseann Bayne 2 2017 Data $31,387 180 square miles Not even one stop light Median house value: $72,000 60% free & reduced $44,890 $56,505 Brain, Body, Emotion 2020 Roseann Bayne 3 At the age of 43 I learned for the first time that my mom had 6 ACES. Nonetheless, she raised 5 children who all have 0 ACES. Burning Question: How was her resiliency developed? Brain, Body, Emotion 2020 Roseann Bayne 4 Mental Health is not just the presence or absence of a disorder Mental Health is a Continuum of Wellness There is no perfect state--we often go back and forth on this spectrum and that is completely healthy 1. Do you have skills to cope with whatever emotions you are having in a healthy way? 2. How are we helping students to understand our mental health will ebb and flow, but we need to develop the skills to return to our stable self? Brain, Body, Emotion 2020 Roseann Bayne 5 Humans are hard wired for some basic aspects of life, but we rely on caregivers for survival and development more than most creatures Brain, Body, Emotion 2020 Roseann Bayne 6 blue wildebeest: Walks within 30 minutes of birth, can outrun predators within 24 hours of birth HARD WIRED australian brush turkey: (megapode) Born absent of parent, eyes open, feeds self, flies on day of hatching 7 Brain, Body, Emotion 2020 Roseann Bayne In comparison, humans generally take 10-16 months just to learn how to walk LIVE WIRED Brain, Body, Emotion 2020 Roseann Bayne 8 Brain, Body, Emotion 2020 Roseann Bayne